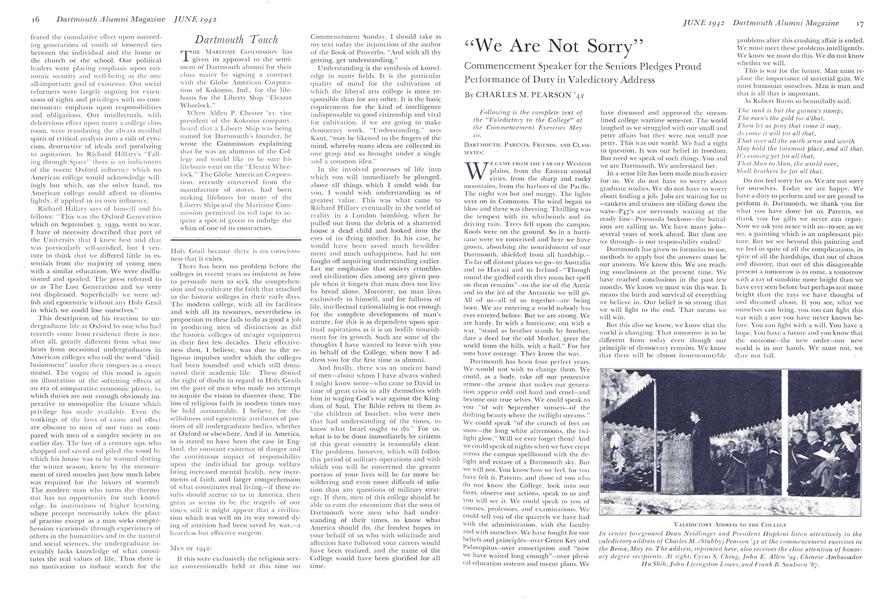

President Hopkins at Baccalaureate Asks of Graduating Seniors "And with All Thy Getting, Get Understanding"

The complete text of the briefBaccalaureate Address of PresidentHopkins and his Valedictory to theclass of 1942 follows:

CONGRATULATIONS IN A PERIOD LIKE THIS may have a hollow sound to such men as yourselves,—a class the Convocation of whose opening days in the College was displaced by the great hurricane and the program of whose graduation exercises is being radically amended by world revolution. Nevertheless, without ignoring the hazards or minimizing the difficulties, the offsetting fact exists that for men of your generation, more and greater opportunities to live importantly will be available than have ever been offered to any generation of mankind in human history. Among intelligent men, dominated in any degree by desire to live usefully among their fellows, it would seem that there could be no question of choice between opportunity to make their lives as significant as yours can be made and acceptance of the limitations and sacrifices even of so difficult an epoch as that in which we live.

There is an element of timing that is indispensable for life to be important, as the world appraises importance, and there is more probability of this working in favor of yourselves as individuals or as a group at a time like the present than under normal circumstances. Philip Guedalla, in his "Footnote on Greatness," comments on the fact that Napoleon, born at any other time than just when he was born, would have missed opportunity and presumably would have been just another bureaucrat of minor rank. He then goes on to speak of success as a chemical compound of man with moment. "Combined," he says, "they are irresistible, but the man without the moment is as futile as the moment without the man is pathetic, an empty pause in history." Assuredly the futility of men with- out their moments cannot be yours!

In this connection, likewise, I would repeat what I said to the College in its opening Convocation a decade ago,—that for youth in a democracy, change is enlarged opportunity. There are qualifications, to be sure, which ought to be made in regard to this statement, such as that if the change should be towards Nazism or Fascism, opportunity would become nonexistent. Holding, however, to our faith that democracy can and will safeguard itself, the contention stands, so far as those are concerned who, like yourselves, are just now being summoned to manhood's responsibilities.

A radical transformation in the pattern of life is bewildering and in many cases tragically unfair to those who have won established position and security through accepting the existing code in good faith and operating under it with due sense of public responsibility. But for youth, on life's threshold, there is a challenge and a stimulus in the possibilities oEered by a radical change in conditions and the opportunity to file entries on even terms with any in competition for the rewards of life. Furthermore, the evidence of history is too convincing to be disregarded that for individuals and for peoples, strength and capability develop disproportionately un- der conditions of hardship and struggle as compared with times of ease and plenty. Maintenance of the status quo or of condi- tions of economic surplus may insure phys- ical comfort and peace of mind but under the inscrutable laws of life, completer realization of human capability grows out of economic scarcity and out of conditions attended with grave problems and baffling difficulties.

It was with such convictions in mind that many of us, concerned with the tendencies of college education in recent years, feared the cumulative effect upon succeeding generations of youth of loosened ties between the individual and the home or the church or the school. Our political leaders were placing emphasis upon economic security and well-being as the one all-important goal of existence. Our social reformers were largely arguing for extensions of rights and privileges with no commensurate emphasis upon responsibilities and obligations. Our intellectuals, with deleterious effect upon many a college class room, were translating the always needful spirit of critical analysis into a cult of cynicism, destructive of ideals and paralyzing to aspiration. In Richard Hillary's "Falling through Space" there is an indictment of the recent Oxford influence which no American college would acknowledge willingly but which, on the other hand, no American college could afford to dismiss lightly, if applied to its own influence.

Richard Hillary says of himself and his fellows: "This was the Oxford Generation which on September 3, 1939, went to war. I have of necessity described that part of the University that I knew best and that was particularly self-satisfied, but I venture to think that we differed little in essentials from the majority of young men with a similar education. We were disillusioned and spoiled. The press referred to us as The Lost Generation and we were not displeased. Superficially we were selfish and egocentric without any Holy Grail in which we could lose ourselves."

This description of his reaction to undergraduate life at Oxford by one who had recently come from residence there is not, after all, greatly different from what one hears from occasional undergraduates in American colleges who roll the word "disillusionment" under their tongues as a sweet morsel. The vogue of this mood is again an illustration of the softening effects of an era of comparative economic plenty, in which duties are not enough obviously imperative to monopolize the leisure which privilege has made available. Even the workings of the laws of cause and effect are obscure to men of our time as compared with men of a simpler society in an earlier day. The boy of a century ago, who chopped and sawed and piled the wood by which his house was to be warmed during the winter season, knew by the measurement of tired muscles just how much labor was required for the luxury of warmth. The modern man who turns the thermostat has no opportunity for such knowledge. In institutions of higher learning, where precept necessarily takes the place of practise except as a man seeks comprehension vicariously through experiences of others in the humanities and in the natural and social sciences, the undergraduate inevitably lacks knowledge of what constitutes the real values of life. Thus there is no motivation to induce search for the Holy Grail because there is no consciousness that it exists.

There has been no problem before the colleges in recent years so insistent as how to persuade men to seek the comprehension and to cultivate the faith that attached to the historic colleges in their early days. The modern college, with all its facilities and with all its resources, nevertheless in proportion to these fails to do as good a job in producing men of distinction as did the historic colleges of meager equipment in their first few decades. Their effectiveness then, I believe, was due to the religious impulses under which the colleges had been founded and which still dominated their academic life. These denied the right of doubt in regard to Holy Grails on the part of men who made no attempt to acquire the vision to discover these. The loss of religious faith in modern times may be held accountable, I believe, for the selfishness and egocentric attributes of portions of all undergraduate bodies, whether at Oxford or elsewhere. And if in America, as is stated to have been the case in England, the constant existence of danger and the continuous impact of responsibility upon the individual for group welfare bring increased mental health, new increments of faith, and larger comprehension of what constitutes real living,—if these results should accrue to us in America, then great as seems to be the tragedy of our times, still it might appear that a civilization which was well on its way toward dying of attrition had been saved by war,—a heartless but effective surgeon.

MEN OF 1942:

If this were exclusively the religious service conventionally held at this time on Commencement Sunday, I should take as my text today the injunction of the author of the Book of Proverbs, "And with all thy getting, get understanding."

Understanding is the synthesis of knowledge in many fields. It is the particular quality of mind for the cultivation of which the liberal arts college is more responsible than for any other. It is the basic requirement for the kind of intelligence indispensable to good citizenship and vital for cultivation, if we are going to make democracy work. "Understanding," says Kant, "may be likened to the fingers of the mind, whereby many ideas are collected in one grasp and so brought under a single and a common idea."

In the involved processes of life into which you will immediately be plunged, above all things which I could wish for you, I would wish understanding as of greatest value. This was what came to Richard Hillary eventually in the world of reality in a London bombing, when he pulled out from the debris of a shattered house a dead child and looked into the eyes of its dying mother. In his case, he would have been saved much bewilder- ment and much unhappiness, had he not fought off acquiring understanding earlier. Let me emphasize that society crumbles and civilization dies among any given peo- ple when it forgets that man does not live by bread alone. Moreover, no man lives exclusively to himself, and for fullness of life, intellectual rationalizing is not enough for the complete development of man's nature, for this is as dependent upon spir- itual aspirations as it is on bodily nourish- ment for its growth. Such are some of the thoughts I have wanted to leave with you in behalf of the College, when now I ad- dress you for the first time as alumni.

And finally, there was an ancient band of men—about whom I have always wished I might know more—who came to David in time of great crisis to ally themselves with him in waging God's war against the Kingdom of Saul. The Bible refers to them as "the children of Issacher, who were men that had understanding of the times, to know what Israel ought to do." For us, what is to be done immediately by citizens of this great country is reasonably clear. The problems, however, which will follow this period of military operations and with which you will be concerned the greater portion of your lives will be far more bewildering and even more difficult of solution than any questions of military strategy. If then, men of this college should be able to earn the encomium that the sons of Dartmouth were men who had understanding of their times, to know what America should do, the fondest hopes in your behalf of us who with solicitude and affection have followed your careers would have been realized, and the name of the College would have been glorified for all time.

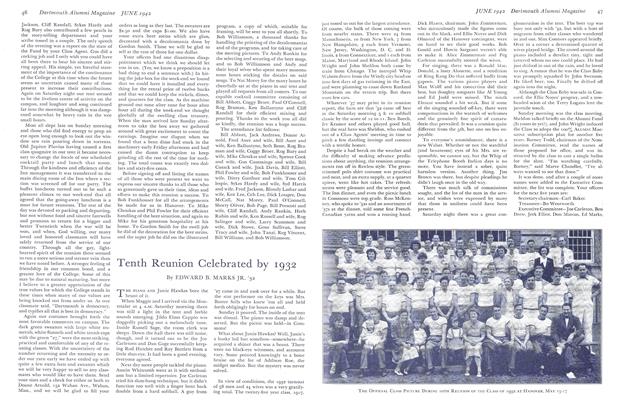

"GRAND OLD SENIORS"

The procession forms for Class Day withthe first row, left to right, Douglas Stowell,marshal; ]ames J. Mulligan, U. S. CoastGuard; John de la Montagne, and Dale E.Bartholomew, president of the class of 1942.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleCollege Graduates Return

June 1942 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1927 Has Its Quindecennial

June 1942 By DOANE ARNOLD '27 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1937 Holds Its Fifth Reunion

June 1942 By JOHN H. DEVLIN JR. '37 -

Class Notes

Class Notes'Seventeen's Silver Jubilee Wins Cup

June 1942 By MOTT D. BROWN JR. '17 -

Article

ArticleFirst War Class Graduates

June 1942 -

Class Notes

Class NotesThirty-Fifth Reunion of 1907

June 1942 By H. RICHARDSON LANE '07

Article

-

Article

ArticleFEWER SOPHOMORES PLEDGED THAN LAST YEAR

NOVEMBER 1927 -

Article

Article15 Leading Glasses in Giving

January 1954 -

Article

ArticleMagazine Appointments

OCTOBER 1967 -

Article

ArticleSkiing

April 1962 By DAVE ORR '57 -

Article

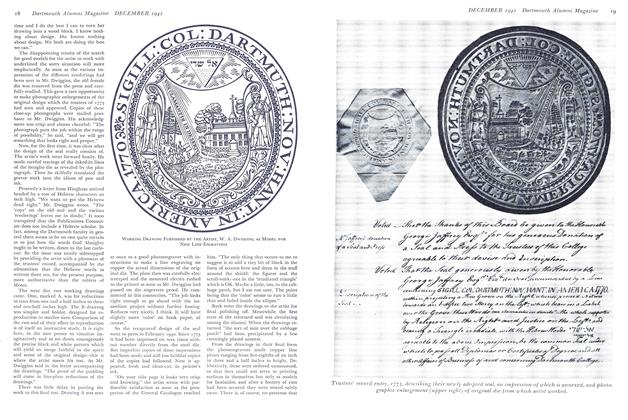

ArticleRediscovering the College Seal

December 1941 By RAY NASH -

Article

ArticleThayer School

June 1957 By WILLIAM P. KIMBALL '29