Sri Ramakrishna

To THE EDITOR: Looking again through the March issue of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE, I was much interested recently to discover in "Hanover Browsing," Henry Miller's recommendation of the Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna, and would like to give the recommendation a hearty second. It might interest you to know that one Dartmouth alumnus has been a follower of the teachings of Sri Ramakrishna for more than ten years.

I first became acquainted with the life of the great Hindu mystic in 1933, during a study of Indian philosophy and religion, and was so deeply impressed with the universality -and the rational basis of his teachings that during the winter of 1933-35 I went to India to study them firsthand. Like many another individual of today, I had been reared in orthodox Christianity and still retained a reverence for the church and its teachings; but since college days had never been able to reconcile a doctrine based on faith with the rational and impersonal views of modern science. Though willing to acknowledge the possibility of mystical awareness or superconscious experience, I could not see how or why it was possible.

I spent a little over three months in India, during which time I was privileged to be the guest of the Ramakrishna Math, the monastic order founded by Sri Ramakrishna before his death in 1886. I visited the Order's monasteries, hospitals, schools and orphanages in many parts of northern India; and found a practical harmonizing of the spiritual paths of mystical contemplation and unselfish service which is a thing unique in the world today.

Sri Ramakrishna held that the only aim of life is to attain God-vision; or, to put it in another way, to experience the Ultimate Reality. This was nothing new in Hindu religion and philosophy; it has been one of the basic ideas of Hinduism for thousands of years. But Sri Ramakrishna's life was unique in two respects: first, that he actually demonstrated in his life the truth and validity of Divine vision; and secondly that he attained to God-vision by following the teachings of all the great religions of the world and thereafter declared all religions to be equal and effective paths to the same identical goal. No other individual in religious history has ever preached the oneness of all religions and demonstrated the truth of his views by his own superconscious experience.

To doubt the validity of mystical experience may be a healthy sign of thoughtfulness, but to scoff at it is simply a confession of stupidity and ignorance. Many of Sri Ramakrishna's great disciples were men highly educated and trained according to western standards before they knew him. They were often skeptical of his visions at first. But so vivid was the spiritual manifestation in him, and so frequently did it recur day after day throughout his life, that even the most doubtful of them in the end acknowledged that his experiences were real. Furthermore, he explained them in so rational a way that they could find no contradiction between them and the teachings of modern science. The only discrepancy was that science, concerned only with description of material phenomena, barely scratched the surface of the Reality which is revealed by superconscious experience to be, in its ultimate form, pure spirit.

True to his own teaching that all religions are valid and effective paths to the same goal, Sri Ramakrishna did not found another religious sect. The monastic order bearing his name includes followers of many of the great religions of the earth. The Order does not believe in conversion to Vedanta, the basic Hindu philosophy upon which his teachings are based, as a necessity for "salvation." And today, monks of the Order are doing spiritual service and teaching not only in India but in Europe, South America, and in nine major cities of the United States from Boston to Seattle and Los Angeles.

The great significance of Sri Ramakrishna's life to the modern man is, if I may judge from my own experience, that it shows him a rational basis for the spiritual urge which is deeper than instinct in him, but which has been inhibited by the overpowering materialism and skepticism of today. There has never been anything wrong with religion except the way it has been presented to us in the West. And if there was ever a time in history when man needed to be sure of the inherently spiritual nature of his true self, it is today, when we face the task of rebuilding the culture which we see being battered to pieces in the intensity and bitterness of the war.

President Hopkins has pointed out that theessential purpose of education is the searchfor reality, and voiced the hope that the College may always be accurate in interpretation of it. It seems to me that if the College isto stand true to this ideal, and if the post-warcollege generation is to have a true perspective on the problems that will then face theworld, Dartmouth cannot escape responsibility for a searching revaluation of the nature and significance of spiritual reality andfor a greater emphasis upon both religionand philosophy in the curriculum. And it ismy personal conviction that, to gain an accurate interpretation of spiritual values, weshall have to look to the Orient for additionallight on the subject.

San Franciscq, Calif.

Aviation Courses

To THE EDITOR : I am inclined to believe that there will have to be military training for every American, but let's not include it as part of the college education. Aviation training is not included in this, and I believe that Dartmouth should look into this feature thoroughly. I offer two ideas of which the latter is my choice. Either have compulsory military training during the summer months or after graduation. Under no circumstances have it during the college year. I think that perhaps the best argument for the latter is that the military training would help to round out the man and make him better fitted for after life. But the biggest mistake of all would be to try to incorporate it into some sort of an R.O.T.C. idea. There is no place for military training at Dartmouth.

As for aviation training, that's a different story. I think that the College should make every effort to obtain facilities for an airport. I think, too, that they should own their own training planes as well as a few for executive use. Aviation is going to be such a big thing that courses should be looked into now with an eye toward fitting them in. History of aviation, airfield planning, C.A.A. ground school courses, etc., should be anticipated. I think that it might even be wise to think about having aviation courses in Tuck School.

As for changing the four-year course to the present streamlined system, I say, "Emphatically No." Let it go for the duration but aftei the war go back to the old system. Don't try to rush someone through the four finest years of his life. It's over fast enough as it is.

Lt. (jg), USNR.

Liberal Education

TO THE EDITOR: Out of four years at Dartmouth I developed a tolerance towards people whose aims and ideas did not agree with mine. I also learned to acclimate myself to new and varying conditions. This tolerance and ability to acclimate myself has stood me in good stead in dealing with men and officers of our own country as well as with those of our allies. I have often thought that one of the greatest things that Dartmouth did for its family was to bring together boys from all parts of the country and let them get acquainted with each other. Dartmouth also taught me that one had to be independent and yet give a good deal to others in order to get the most out of life. I hope I have made myself slightly intelligible on this point.

I received so much from my undergraduate days at Dartmouth that it is hard for me to think of anything that the College failed to give me. I believe that I benefited most from the courses that at least exposed me to the varying thoughts by present and past men of some substance. Of these courses the best were those that looked at these men's ideas from a critical viewpoint and compared them. I retained more ideas from such courses than I did from such courses as mathematics and chemistry, which undoubtedly gave me some good mental exercises but very little original thought. This probably can be laid to the fact that my natural leaning is not toward such fields.

I believe that men of college age should be given a chance to explore the various social theories so that they can understand more clearly why they prefer (or do not) the social environment in which they live.

After the war there may be more demand than ever to specialize. This would mean that a college education might not be enough. I think this has been a development that has occurred in the last ten years. Nevertheless, I think that it is of the greatest value that a young man have a chance to get a liberal education prior to entering his specialty. I know in my case that my specialty of a legal career was very much benefited by the liberal arts course I followed as an undergraduate at Dartmouth. A person with nothing but a specialized training is often a pretty dull person to his associates and himself. He does not, I am sure, get as much out of life. I am, therefore, heartily in favor of a return to the pre-war program of the college with possibly a greater stress on pricking or bringing to life a student's curiosity and awareness of what goes on in other people's minds and in other parts of the world. Such an understanding can not help but lead to a better peace, temporary as it may be.

Lt., USNR.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

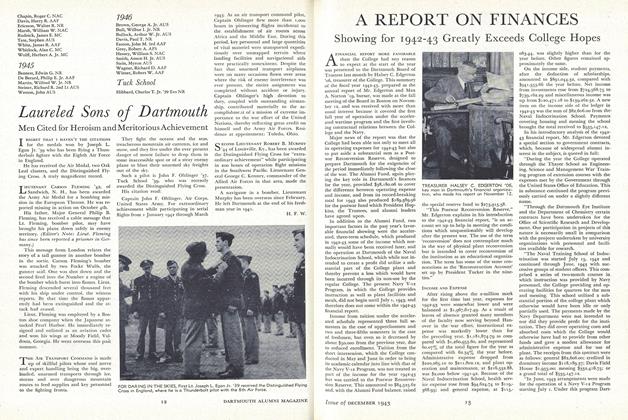

ArticleV-12 PHYSICAL TRAINING

December 1943 By C. E. W. -

Article

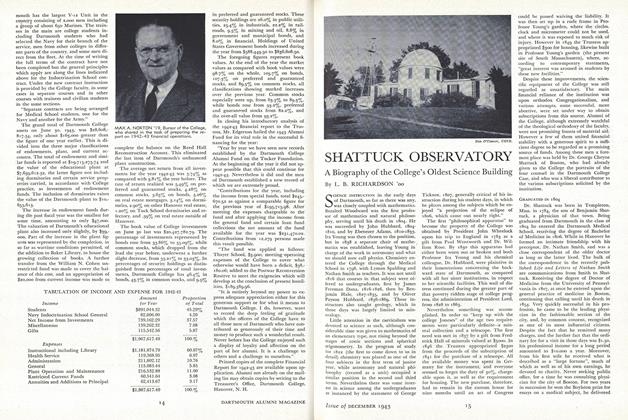

ArticleA REPORT ON FINANCES

December 1943 -

Class Notes

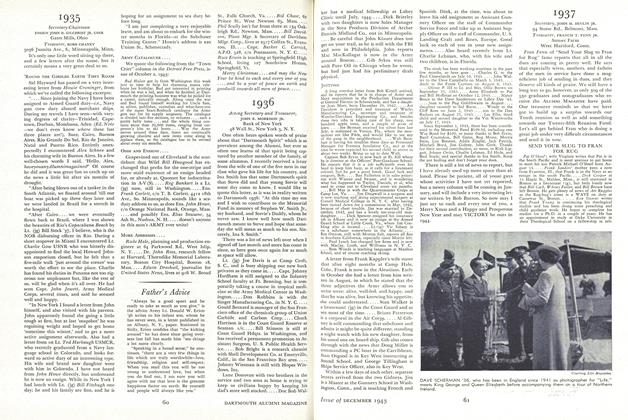

Class Notes1937

December 1943 By JOHN H. DEVLIN JR., FRANCIS T. FENN JR. -

Article

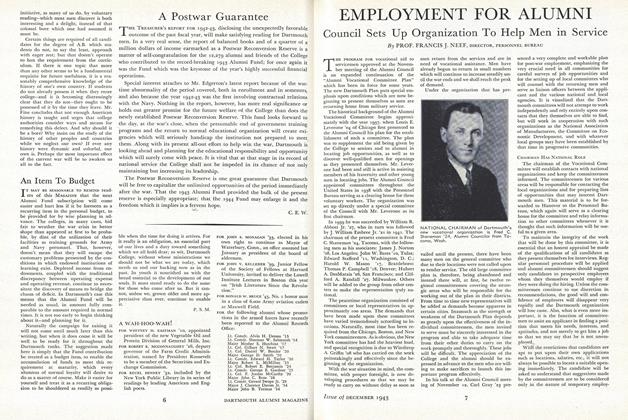

ArticleEMPLOYMENT FOR ALUMNI

December 1943 By PROF. FRANCIS J. NEEF -

Class Notes

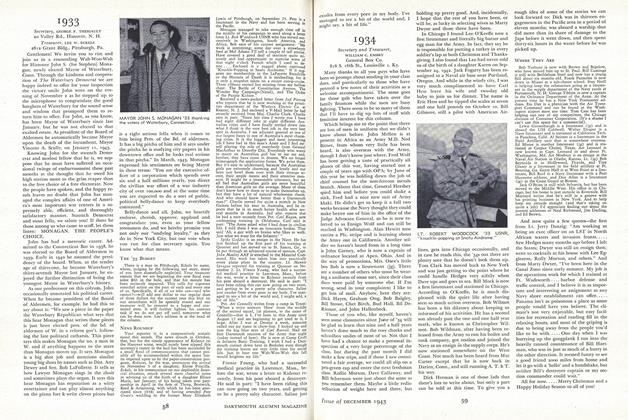

Class Notes1933

December 1943 By GEORGE F. THERIAULT, LEE W. ECKELS -

Article

ArticleSHATTUCK OBSERVATORY

December 1943 By L. B. RICHARDSON '00

Letters to the Editor

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters from Dartmouth Men in the Armed Forces

October 1943 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

APRIL 1967 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

JUNE 1970 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

Mar/Apr 2005 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

Jan/Feb 2007 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

Sept/Oct 2011