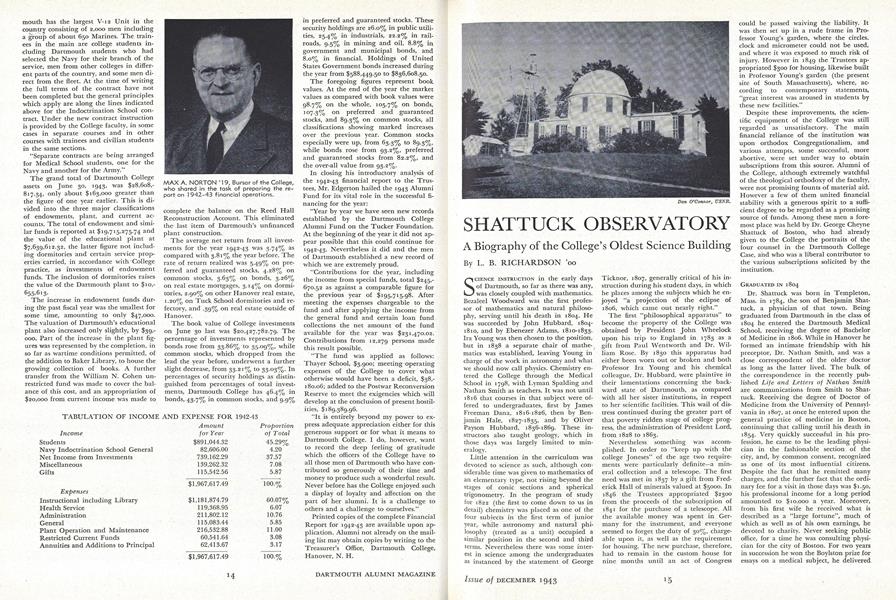

A Biography of the College's Oldest Science Building

SCIENCE INSTRUCTION in the early days of Dartmouth, so far as there was any, was closely coupled with mathematics. Bezaleel Woodward was the first professor of mathematics and natural philosophy, serving until his death in 1804. He was succeeded by John Hubbard, 1804- 1810, and by Ebenezer Adams, 1810-1833. Ira Young was then chosen to the position, but in 1838 a separate chair of mathematics was established, leaving Young in charge of the work in astronomy and what we should now call physics. Chemistry entered the College through the Medical School in 1798, with Lyman Spalding and Nathan Smith as teachers. It was not until 1816 that courses in that subject were offered to undergraduates, first by James Freeman Dana, 1816-1826, then by Benjamin Hale, 1827-1835, and by Oliver Payson Hubbard, 1836-1869. These instructors also taught geology, which in those days was largely limited to mineralogy.

Little attention in the curriculum was devoted to science as such, although considerable time was given to mathematics of an elementary type, not rising beyond the stages of conic sections and spherical trigonometry. In the program of study for 1822 (the first to come down to us in detail) chemistry was placed as one of the four subiects in the first term of junior year, while astronomy and natural philosophy (treated as a unit) occupied a similar position in the second and third terms. Nevertheless there was some interest in science among the undergraduates as instanced by the statement of George Ticknor, 1807, generally critical of his instruction during his student days, in which he places among the subjects which he enjoyed "a projection of the eclipse of 1806, which came out nearly right."

The first "philosophical apparatus" to become the property of the College was obtained by President John Wheelock upon his trip to England in 1783 as a gift from Paul Wentworth and Dr. William Rose. By 1830 this apparatus had either been worn out or broken and both Professor Ira Young and his chemical colleague, Dr. Hubbard, were plaintive in their lamentations concerning the backward state of Dartmouth, as compared with all her sister institutions, in respect to her scientific facilities. This wail of distress continued during the greater part of that poverty ridden stage of college progress, the administration of President Lord, from 1828 to 1863.

Nevertheless something was accomplished. In order to "keep up with the college Joneses" of the age two requirements were particularly definite—a mineral collection and a telescope. The first need was met in 1837 by a gift from Frederick Hall of minerals valued at $5OOO. In 1846 the Trustees appropriated $2300 from the proceeds of the subscription of 1841 for the purchase of a telescope. All the available money was spent in Germany for the instrument, and everyone seemed to forget the duty of 30%, chargeable upon it, as well as the requirement for housing. The new purchase, therefore, had to remain in the custom house for nine months until an act of Congress could be passed waiving the liability. It was then set up in a rude frame in Professor Young's garden, where the circles, clock and micrometer could not be used, and where it was exposed to much risk of injury. However in 1849 the Trustees appropriated $3OO for housing, likewise built in Professor Young's garden (the present site of South Massachusetts), where, according to contemporary statements, "great interest was aroused in students by these new facilities."

Despite these improvements, the scientific equipment of the College was still regarded as unsatisfactory. The main financial reliance of the institution was upon orthodox Congregationalism, and various attempts, some successful, more abortive, were set under way to obtain subscriptions from this source. Alumni of the College, although extremely watchful of the theological orthodoxy of the faculty, were not promising founts of material aid. However a few of them united financial stability with a generous spirit to a sufficient degree to be regarded as a promising source of funds. Among these men a foremost place was held by Dr. George Cheyne Shattuck of Boston, who had already given to the College the portraits of the four counsel in the Dartmouth College Case, and who was a liberal contributor to the various subscriptions solicited by the institution.

GRADUATED IN 1804

Dr. Shattuck was born in Templeton, Mass. in 1784, the son of Benjamin Shattuck, a physician of that town. Being graduated from Dartmouth in the class of 1804 he entered the Dartmouth Medical School, receiving the degree of Bachelor of Medicine in 1806. While in Hanover he formed an intimate friendship with his preceptor, Dr. Nathan Smith, and was a close correspondent of the older doctor as long as the latter lived. The bulk of the correspondence in the recently published Life and Letters of Nathan Smith are communications from Smith to Shattuck. Receiving the degree of Doctor of Medicine from the University of Pennsylvania in 1807, at once he entered upon the general practice of medicine in Boston, continuing that calling until his death in 1854. Very quickly successful in his profession, he came to be the leading physician in the fashionable section of the city, and, by common consent, recognized as one of its most influential citizens. Despite the fact that he remitted many charges, and the further fact that the ordinary fee for a visit in those days was $1.50, his professional income for a long period amounted to $lO,OOO a year. Moreover, from his first wife he received what is described as a "large fortune", much of which as well as of his own earnings, he devoted to charity. Never seeking public office, for a time he was consulting physician for the city of Boston. For two years in succession he won the Boylston prize for essays on a medical subject, he delivered the annual address to the Massachusetts Medical Society in 1828 and was its president from 1836 to 1840. He was also president of the American Statistical Society from 1846 to 1851. Active in medical journalism, he had much to do with the foundation and management of the New England Medical Journal, the Massachusetts Dispensatory, and assisted Dr. James Thatcher in the preparation of the American Medical Biography.

Dr. Shattuck was a man of wide charitable instincts. Visited by students of Harvard or Andover whose appearance seemed to him to be somewhat threadbare, not only did he make no charge for his services, but asked the favor that they should deliver a note at a point in the city near the pharmacy where their prescriptions were to be filled. The note, upon delivery, turned out to be an order upon a tailor for a suit of clothes. To the Harvard Medical School he gave $26,000, including $14,000 for the establishment of a chair of pathological anatomy. He was especially successful in setting up a dynasty of medical Shattucks in Boston, five successive generations, including his own, being active in the city in medical practice or teaching, or in the conduct of medical journals. Among them was his son, Dr. George Cheyne Shattuck, Professor in the Harvard Medical School and founder of St. Paul's School at Concord, N. H.

PURCHASES MADE ABROAD

In 1852 Professor Young succeeded in infer.esting Dr. Shattuck in the needs of his department. In two letters the professor set forth the expense of erecting an observatory and securing apparatus to place Dartmouth on a parity with other institutions of its class. His minimum estimate was $7OOO, with desirable additional expenditure amounting to some $2OOO more. Whereupon Dr. Shattuck offered, subject to certain conditions, to contribute $7OOO to meet these needs, as well as a sum which eventually amounted to $1790 for the purchase of books. One of the conditions was that Professor Young should visit Europe at college expense to purchase in person the needed equipment and books. To the latter appropriation was added a gift of $lO5O from Professor Roswell Shurtleff and $760 of college funds. Accordingly, accompanied by his son Charles A., of the graduating class. Professor Young spent the months from April to September, 1853 in England and on the continent, purchasing equipment valued at $2530 and books at an expense of $3750.

In the meantime the erection of the observatory was going on in Hanover un- der the direction of Professor Hubbard, who was.paid $l.OO a day for 126 days for his supervision. Ammi B. Young, architect of Wentworth, Thornton and Reed Halls, showed his versatility in aiding in the design of the new building, modeled, it is said, upon the Lassell Observatory at Liverpool. The structure cost $4715 and the Trustees were obliged to borrow about S4OOO to meet the total expenditure for erection and equipment. It was ready for use in the fall of 1854, with the telescope already in possession of the College installed in the dome.

Professor Ira Young died in 1858, being succeeded in the chair of astronomy by James W. Patterson and in that of natural philosophy by Henry Fairbanks. The chairs were united again in 1866 under Professor Charles A. Young. The eleven years of his service at Dartmouth were the golden age of the observatory—a period in which the investigations of Professor Young in the new science of spectroscopy raised him to a foremost rajik among world authorities in astrophysics and knowledge of the sun. A new telescope of 9.4 inches aperture and 12 feet focal length was secured in 187 a through private subscription, together with other instruments necessary to Professor Young's work. His departure to Princeton in 1877 was regarded as a real calamity to the College. Nevertheless nearly all the work which won him his fame was carried out at the Shattuck Observatory.

In more recent times, although the external appearance of the building is much the same as it was in 1855, the equipment has been largely reconstructed and added to meet modern conditions. The observatory is now the oldest of the scientific buildings of the College.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleV-12 PHYSICAL TRAINING

December 1943 By C. E. W. -

Article

ArticleA REPORT ON FINANCES

December 1943 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1937

December 1943 By JOHN H. DEVLIN JR., FRANCIS T. FENN JR. -

Article

ArticleEMPLOYMENT FOR ALUMNI

December 1943 By PROF. FRANCIS J. NEEF -

Class Notes

Class Notes1933

December 1943 By GEORGE F. THERIAULT, LEE W. ECKELS -

Class Notes

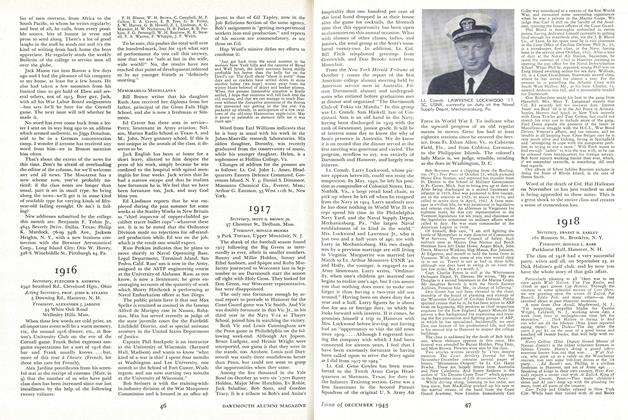

Class Notes1917

December 1943 By MOTT D. BROWN JR., DONALD BROOKS

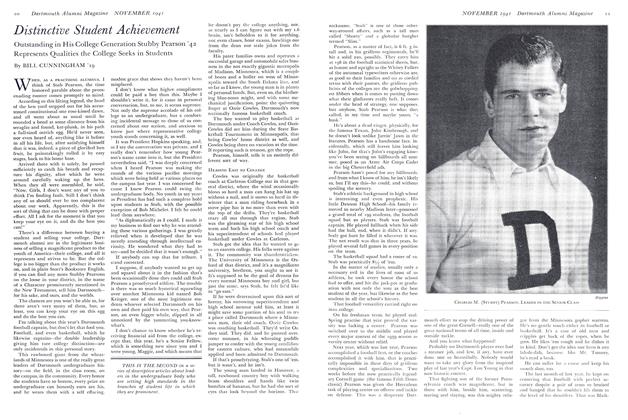

L. B. RICHARDSON '00

Article

-

Article

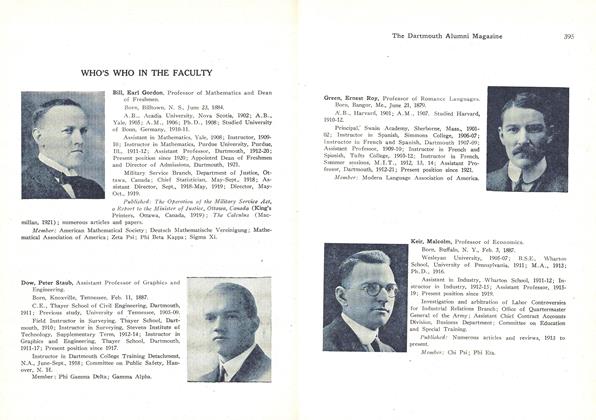

ArticleWHO'S WHO IN THE FACULTY

March, 1923 -

Article

ArticleTHOUSANDS OF BRICKS AROUND NEW LIBRARY SITE

MARCH, 1927 -

Article

ArticleDefense Group Galls for No Compromise

November 1941 -

Article

ArticleMasthead

MAY 1996 -

Article

ArticleParkhurst Renovated

June 1951 By C. E. W. -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

January 1957 By HERBERT F. WEST '22