Letters from Dartmouth Men in the Armed Forces

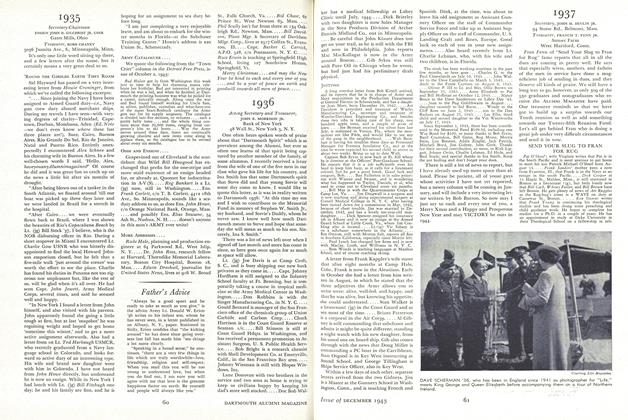

I AM. grateful for the opportunity to reproduce one of MAJOR JAMES A.DONOVAN JR's pictures and print a letter of his from Guadalcanal. Jim: was amember of the Class of 1939, and was arteditor of the Jack o' Lantern. He alsostudied under Paul Sample, Artist inResidence.

Major Donovan's letter follows:

The fighting on land here is over, the Japs were pushed back to the Cape, surrounded, cut off, and surrendered or were killed. Their scattered remnants, a few hundred or so, were mostly all sick or starving. There are undoubtedly many hiding in the back-country but they are ineffective and will either give themselves up or starve. So the island is ours now, after six months of sweat, blood and heart-breaking work on the part of thousands of men—and only those who have fought here will ever appreciate what a hell-hole this has been.

We just got in on the kill, (written in February, 1943) the Japs were doomed before we landed, but we saw enough of it and had our hard days and took our losses and appreciate what the men who were here so long did. There was never an American battlefield any more difficult or any battlefield where Americans have fought where more was accomplished than by the first Marines who landed here.

Today, we moved back from the so called "front," the artillery had ceased firing for about twenty-four hours and as I came back over the dusty, rutted coast road, along the seven or eight mile strip we had fought and marched on, everything seemed strangely quiet, the road wasn't choked with trucks and jeeps as it had been, there wasn't any confusion, there were bridges over the streams. Men were washing clothes and sitting in the sun, an artillery battery was moving out, even the shattered palms seemed relaxed.

And as I came back over the road, I saw where we had stopped at night, where we had been held up by machine guns one day, where John had been shot, the hole I slept in the night we were shelled, our old dugouts—all deserted and peaceful now.

So we had come back to the cocoanut grove and will wait for the ships to come and take us out. It should be quiet and restful—and boring. We can watch the ships come and go and see the fighters and bombers go out each day to pay Tojo a visit—and then of course the Nips may pay us an air visit; whenever they come though, they get cut to pieces—and we can keep it up as long as they like. It will take a pretty tremendous effort for the Japs to take this place back and it's going to be a bad thorn in their side.

This could be a very nice spot if it were cleaned up—it's really a beautiful example of the tropics. Of course it will always bear the scars of the fight here but things grow fast in the tropics and soon much of the damage will be covered over.

Someday there will be Marine barracks here and it will be another Marine outpost. Perhaps they will even clean up the malaria

We are in a very pleasant bivouac in the cocoanut grove., on the beach and surrounded by little rivers, islets and lagoons. This could be a tropic paradise. It's amazing how the tropics slow a white man down. We all move slowly, talk in low voices and get quite lethargic.

Through the courtesy of The Providence Sunday Journal I am free to printa letter from Sicily written by their formerreporter CORPORAL JOHN W. LITTLE '40, son of LESTER K. LITTLE '14.

Somewhere in Sicily.—There's a song I remember singing a long time ago, it might have been in Joseph Jenks junior high school, Bawtucket, or for that matter at Grove street school, same city. It starts out, "Hail Rhode Island gem o£ beauty, jewel on New England's shore" and is sung to the tune of the German national anthem.

Back home in Rhode Island that song always sounded quite a bit smug, especially when driving down Water street past Carey's Cafe or trying to see through the smoke from the city dump out on Prospect street, Pawtucket, where the smell of burning trash stays in your car until you are almost in Warren.

However, here in Sicily, those words don't sound too bad; "Little Rhody" has got anything beat I've seen yet and right now I wouldn't mind a little of that dump smoke in my nostrils, it's a better smell than dead things along the road: men, mules, burned out tanks or the smell of brick and masonry blown into powder from a high explosive bomb.

And, incidentally, one reason I'm in Sicily this warm August afternoon instead of getting in some golf with Jack Cumming or Don Blount, out at Pawtucket Golf Club, is that a lot of people who sing that song with the German words, "Deutchland Deutchland über alles, über alles in dem welt" under a certain song leader named Adolf Hitler, have got to be forcefully persuaded by a lot of fellows from Rhode Island and the other 47 States that they are not of the master race, that they are not "over all in the world" as their song goes, but that they are ordinary people, no better or worse than anyone else and must act that way for the common benefit of mankind.

For the last few days my group has been in a town about the size of Warren, but there the resemblance ends. It is one of dozens of Sicilian towns in the mountainous interior of the island, perched right on top of a good steep mountain and flowing a short way down the sides as though the first settler had built his home on the crest and each succeeding settler had tried to get as close as possible to the centre

No COFFEE, SUGAR, TEA FOR TWO YEARS

Unlike Warren with its industries and busy Main street where people flock into the First National and A. & P. markets before a week-end and the Lyric Theatre is usually pretty full, this town is entirely agricultural, the people raise their own food, the few stores have empty shelves and most of the people have never seen a moving picture in their lives.

Commodities such as coffee, sugar, tea and chocolate have not been seen for two years and these and other items such as tobacco, shoes and cloth are far past the rationing stage. There isn't anything to ration.

Until we reached this place, we had been going through towns so fast that it was difficult to retain more than a fleeting impression of the people and character of a particular place. But here, as though we had rushed through an art gallery and finally paused to study one painting, the highlights are not the only things we see.

Out of the shadows of the canvas comes the detail: the brown earthen jugs covered with a cool sweat from the water within, great pink and black hogs that casually wander in and out of people's front doors like pet dogs, the goat herder selling milk right from the goat from house to house in the morning and the narrow cobbled streets filled with the clucking of hens, the clatter of mules and the conversations between people on balconies.

Rather nerve racking at first were the bells in the church bell tower because they were run so frequently that to our they seemed almost incessant. Now we are as accustomed to them as the people, who not only hear the hours and quarters sounded, but the matins, vespers, Ave Marias and the tolling strokes for the dead.

With Bill Jenkins, a Swedish lad from Minnesota, I climbed the worm-eaten stairs of the bell tower yesterday accompanied by the head bell ringer, a garrulous fellow who explained things as we progressed and threw in a condensed "Lives of the Saints." The tour cost us a fee of two cigarettes.

The oldest bell was an iron-tongued bronze monster six feet in diameter at the mouth. It was marked 1544, .a mere 52 years after Columbus discovered America, if I remember correctly

To get back to us here in Sicily and you folks back home, the thing that is closest to every soldier's heart is mail from home. We have coffee, sugar and usually plenty of cigarettes, but the things we miss, that I miss, are sweet corn, clam chowder, the smell of salt marshes and bayberry and the sailboats on Narragansett Bay. The next best thing to the real thing is news of what's going on at home, no matter how trivial, auntie's arthritis, the neighbor's Victory garden and what people are saying and doing in America.

Some weeks ago, scrunched down in a fox-hole near the beach, something I'd heard in Warren last summer popped into my head. I was thinking of Charlie Hughes and his famous Bristol County clambake to which come an uncommon mixture of Republicans and Democrats it: the State and local governments of Rhode Island to amicably eat clams together over at Davis's bake in Touisset.

It was just before the clambake and I was with Charlie at the "Journal office in Warren.

"When you were out, ex-Senator Blank called up and asked for three tickets for the bake," I said to Charlie, naming a prominent political figure in the State.

"Jack," said Charlie, who is pretty independent about his bake, figuring, and rightly so, that people ought to buy tickets at least a few days before the bake so he

can estimate how many are coming, "you tell that big so-and-so to go away and come around again next year."

Just when that little scene was passing through my head, the Messerschmidt came roaring down out of the sun again and Charlie Cody, my Sacramento, Cal., buddy, in the next fox-hole, hollers:

"Jack, will you tell that big so-and-so to go away and come around next year!"

Late in May and during the first part of June while in Africa, I read a poem that made a great impression on me and which I have read many times since. The poem is Amy Lowell's "Lilacs."

I don't intend to explain my reasons for liking it. You can't have a poem explained to you anyway; you just have to read it and find out whether or not you like it.

Sufficient to say that there is a great deal of New England's best essence and flavor in the poem. It concerns New England. It concerns lilacs bursting along New England walls and in New England back yards during that all too short springtime that I had spent in Africa, missing it all.

I like New England in general and Rhode Island in particular. I like oysters, Brown Commencements (though I'm from Dartmouth), Prudence Island blueberries, the woods and ponds near R. I. State College. Also I like the Mt. Hope Bridge, the beach at Misquamicut, the tennis matches at Newport .... and a lot more.

And from Chungking written the lastof August 1943 I print here a fine letterfrom Jack's father, LESTER K. LITTLE'14, acting inspector general of customsfor the Chinese Government.

Three weeks ago yesterday I "crossed the Hump"—as everybody calls it—between India and China and landed at Kuming. The first familiar face I saw was that of Ludden, who was No. 2 in the Consulate at Canton and came as far as Lorenco Marquer last year when we were evacuated. Within a short time I had seen Graff-Smith (now commissioned at Kuming), Maxay-Smith (Canton—"Gripsholm") and half a dozen other old friends. Next day I had half an hour with Gen. Chennault: keep your eye on that man! Then I flew the last lap of my journey, and landed on an island in the Yangtze right under the city of Chungking. I use the word "under" advisedly, for Chungking is perched on a great ledge high above the river. It was sunset as we came in, and a night to be remembered.

The main part of the city is the "North Bank"; but both my house and office are on the "South Bank," and between the Banks flows the swift Yangtze, about g/4 of a mile wide. Transportation is most difficult, and distances are great. From my house to my office is not very far, but it is a hair-raising adventure four times a day, up and down precipitous, narrow and crowded streets—if a 5-ft. passageway can be called a street—carried in a bamboo chair. I have 4 bearers, two at a time, who relieve each other at intervals. The "streets" are really stone steps—thousands and thousands pi them—and the chairbearers are, fortunately, very sure-footed.

My house is large and comfortable, even if very bare-looking, and I am fortunate to have it, because of the acute shortage of houses here. I live on the second floor, the first is occupied by a British and 1 Norwegian Custom Secretaries. (All men, I hasten to add!). I have inherited Joly's boy and cook, and they seem to be good servants. I found waiting for me a letter from my own old cook, who is in Canton and wants to join me. But the journey overland may be too difficult, so I think I'll tell him not to attempt it.

Yesterday I went to a buffet lunch at the American Embassy, in honor of Senators Mead (N. Y.), Russell (Ga.) and Brewster (Me.). There were about 100 people present, and it was my first chance to see most of the Americans. I found I knew a great many of them, and I met some new ones, including Gen. Stilwell. The British Ambassador, Sir Horace Seymour and Lady Seymour were there, as well as the Russian officials.

Prices here are fantastic. A friend of mine paid Chinese $4BO for a pound of coffee last week. The official exchange rate is Ch. §2O—U. S. $1 so he paid the equivalent of U. S. $24. I paid Ch. $3O. (U. S. $1.50) for a hair-cut; formerly it would have cost not more than 10 cents. Hugh Bradley paid Ch. $5OO to have his shoes soled. Servants who used to get Ch. $3O a month now get Ch. $l3OO. Believe me, we soon learn to do without in Chungking!

We had our first air raid in two years last week, but it didn't amount tp much. We had about goo people in one Custom shelter, which is dug out of the solid rock back of our office. Men, women and children—and what a smell! Fortunately, I was able to sit outside practically all the time. We saw planes, and heard some noise, but nothing came within miles of us. The raids are a nuisance, however, because all records, archives, typewriters, etc. have to be carted out of the office and put in ths shelters. This takes time, and more time to get them back, opened and ready to use again.

Hugh Bradley is living in the hills, some 6 miles from the city. I spent last week-end with him, and enjoyed the change. At his elevation, there is a cool breeze almost every night, in Chungking, the dead heat is most depressing. But it is a terrible climb to get to his place. He walks it—what a man! but I was carried. Hugh is leaving China for good next month, and I shall miss him very muchpersonally as well as officially. He doesn't know yet which way he will go home, but if he is in the East, he will surely look you up, can give you a first-hand account of the kind of life we lead here.

As far as my job goes, I can see that it will not be a bed of roses, but, at the same time, I don't think it will be all thorns. Anyhow, we live only once and, whatever happens, I shall have had a not uninteresting experience.

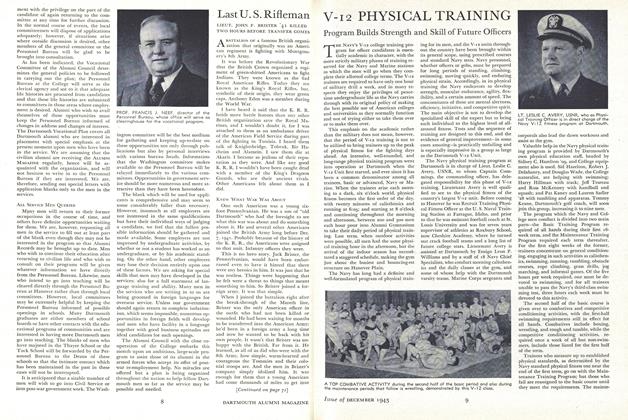

SHORE WATCH ON THE SOLOMONS, one of the sketches which Major James A. Donovan Jr. '39 has made in both Iceland and the South Sea islands while with the Marines.

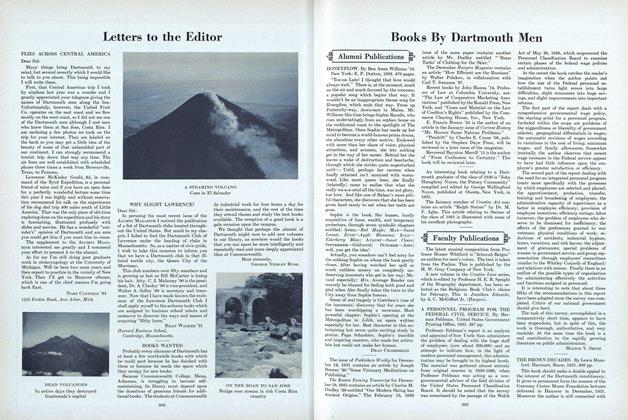

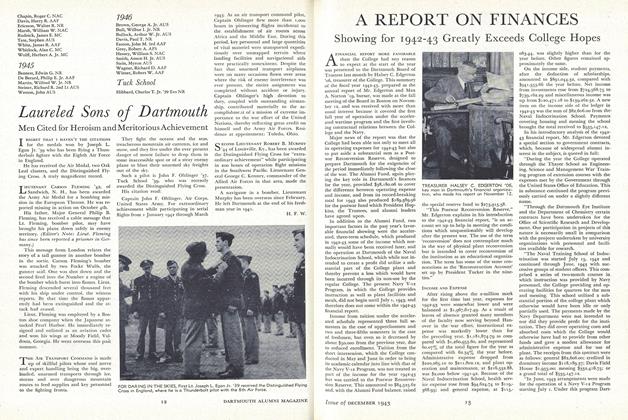

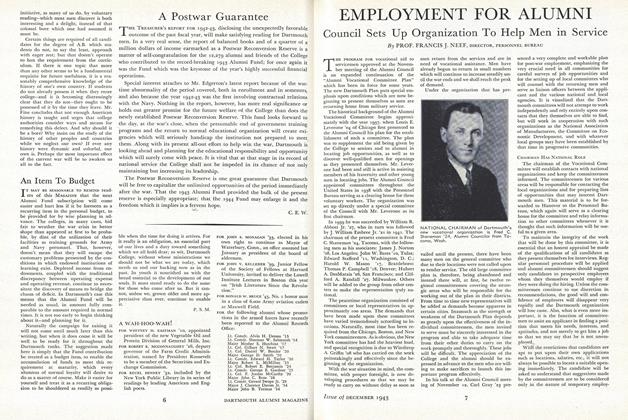

DARTMOUTH ALUMNI AT U. S. NAVAL AIR STATION (NTSI) Quonset Point, Rhode Island. First row, left to right: Lt. (jg) N. M. Bankart '29, Lt. (jg) A. Bolte '30, Lt. (jg) F. L. Sweetser '34, Ensign G. G. Geddes '33, Lt. (jg) W. S. Durgin '30, Lt. (jg) J. W. Knibbs lll '34. Second row, left to right; Lt. (jg) R. Jackson '33, Lt. (jg) H. W. Bryan '34, Ensign L. M. Frick '38, Ensign P. L. Guibord '36, Lt. (jg) W. E. Rench '34, Ensign R. J. Smith '36. Not in picture: Lt. (jg) S. T. Woodbury '34, and Lt. (jg) L. H. Rossiter '30.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleV-12 PHYSICAL TRAINING

December 1943 By C. E. W. -

Article

ArticleA REPORT ON FINANCES

December 1943 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1937

December 1943 By JOHN H. DEVLIN JR., FRANCIS T. FENN JR. -

Article

ArticleEMPLOYMENT FOR ALUMNI

December 1943 By PROF. FRANCIS J. NEEF -

Class Notes

Class Notes1933

December 1943 By GEORGE F. THERIAULT, LEE W. ECKELS -

Article

ArticleSHATTUCK OBSERVATORY

December 1943 By L. B. RICHARDSON '00