A brilliant mind is stilled. The long and courageous struggle with crippling and painful illness is at an end,; the rich store of information and inspiration—is closed.

H. C. P. is gone; and I feel like uttering the despairing cry of Froude who, hearing that Carlyle had passed on, exclaimed "a man is dead."

For more than fifty years H. C. P. and I were associates and friends. We were contemporaries in college, we belonged to the same Greek letter fraternity and the same Senior society, for nearly thirty years we worked side by side in the old Monitor office. Oceans at times separated us, but the tie was never lost. Indeed it was strengthened with each reunion and in these last stricken years our regularly scheduled meetings were mutually solicitous, mutually hopeful and always mutually reminiscent.

Throughout all the years that I have known him I have rarely met, in any land, a mentality more alert and versatile than his. He was a brilliant writer in many widely different fields. As a reporter he sought news diligently and set it down effectively, often with a delicate sense of humor and always with unerring accuracy. He was a sports writer of uncommon ability. He was a dramatic and literary critic far above the average. His editorials were compact and forceful.

He was born to journalism; and with his remarkable equipment for the inken trade he merited a larger field. I cherished his professional companionship, but I often urged him to seek greener pastures and to take his rightful place among those men whose by-line have proved an allure to so many readers all over the land. But he was essentially a shy man and he preferred to stay on here to help make the Concord. Monitor like the ManchesterGuardian in England, a provincial journal of light and leading in its own community. This he did—as can be attested by the successive editors under whom he served.

He was scholarly, but never pedantic; and though his rank in college was among the highest of his generation he found time for many activities not set down in the curriculum and to which he added more than one man's share of generous contribution. The Literary Monthly of those days frequently displayed his name in its table of contents and not a few of his compositions found their way into the collated volumes of Dartmouth verse and prose.

His industry was prodigious and he was methodically forehanded in each of the numerous stated tasks which were laid out by and for him week by week. Almost to the end of his bed-ridden days he was to be found with his typewriter on his bed table, a sheaf of notes at hand and his doublyburdened busy fingers hard to at his tasks of professional and personal writing.

His personality was one which unconsciously but definitely invited both confidence and confidences; and for forty years, with few interruptions, successive Governors of New Hampshire, both Republican and Democratic, as principal secretary. To most of these men he was more; he was guide, philosopher and friend and many state papers under their names owes much to his admonition, learning and skillful literary adaptability.

His charm was freely acknowledged everywhere, but it was in his home it came to its highest expression. His constant solicitude for his wife, his advancing pride in his children were not concealed from his friends and to his family they were a constantly expanding revelation. To them his passing

is a sorrow which friends cannot measure, but which they can share. Over whatever seas he is sailing, Whatever strange winds fan his brow, What company rare he's regaling, I know it is well with him now. And when my last voyage I am making May I go, as he went, unafraid, And, the Pilot that guided him taking, May I make the same port he has made.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleSulzberger Addresses 1943

February 1943 -

Article

Article'Round the Girdled Earth

February 1943 By Herbert F. West '22. -

Article

ArticleColleges Will be Used for Military Training

February 1943 By LLOYD K. NEIDLINGER '23 -

Article

ArticleGovernment War Work

February 1943 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1939

February 1943 By RICHARD S. JACKSON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

February 1943 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES

Article

-

Article

ArticleMasthead

February 1950 -

Article

ArticleCanada's New "Mt. Dartmouth"

December 1959 -

Article

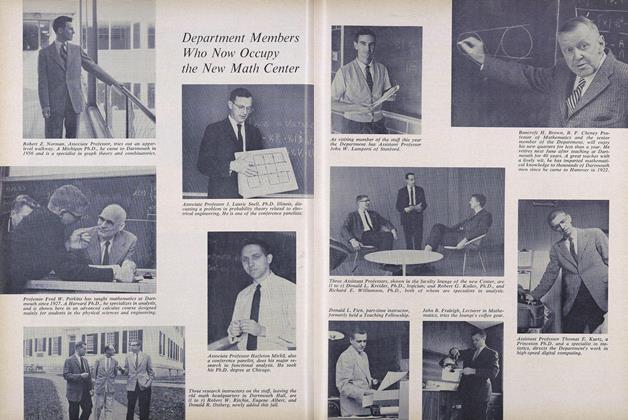

ArticleDepartment Members Who Now Occupy the New Math Center

November 1961 -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH ALUMNI AWARD

FEBRUARY 1964 -

Article

ArticleThe Sages of Hanover

MARCH • 1987 By Lee Michaelides -

Article

ArticleJames Walter Goldthwait

February 1948 By Richard E. Stoiber '32