TO A NAVY SON AGED THREE WEEKS

DEAR JIM: If I figure correctly, you are two weeks old today. You are probably too busy right now to be bothered with letters, but this one happens to be about you and your old man. And that is important.

You started right off being a war baby. The morning you were born, your father, a Lieutenant junior grade, USNR, no less, was scratching his perplexed head in a navigation class at Dartmouth College. That's why you haven't laid eyes on him yet. You will soon, though, and I can tell you, by way of introduction, that he is an officer and a gentleman. I think you'll get along fine.

I can make a prediction like that because I have roomed with Lt. (j.g.) Moreau B. Chambers (like the sound of it?) for six weeks in the good ship S. S. Ripley at Dartmouth, in Hanover, New Hampshire. They are teaching us to be naval officers up here in quite a hurry. We are just about the busiest men you will ever see.

Not too busy, however, to think and talk about you, Jim. For instance, about three weeks before you were born, we fell to talking about where you were going to college. We naturally assumed (how, I wouldn't know) that you would be a boy. Then, with the same easy assumption we took a big leap right over your childhood, measles and all, and had you ready for college!

Now is the moment, Jim, for me to confess to you that I'm a Dartmouth man of the far away class of iggo. Being a Dartmouth man is a kind of career, curious to many people. That's why coming back here was for me a happy coincidence. As for your papa, a man from the south and proud of it, he thought the whole thing was pretty "Yankee." It was all rather strange to him, from the snow driving against the windows to the way down east twang of the natives. He was darkly suspicious of the first time he was served codfish cakes and baked beans.

One night, after study, I tossed out a feeler. "How about sending the boy to Dartmouth?" I asked.

Your father fixed me with a stare. "What's wrong with one of the Southern schools? What's wrong with Duke?"

"Now don't get excited, Moreau," I said. "I just asked a simple question. I didn't attack Southern education." Thus ended that discussion and I knew right then that a little indoctrination was indicated.

A couple of days later I had a faint sense of progress. Your sire and I were taking a walk on the campus during that precious hour called "liberty." Dartmouth Hall was chalk white in the early winter twilight. The bare trees cast their black tracery on the stark whiteness of Dartmouth Hall.

Above us rose the tower of Baker Library and at that moment the bells tolled out the hour. Your father looked up and listened as the echo died away in the hills. "I like those bells," he said. Then after a bit, he added: "I'm beginning to see what you mean about Dartmouth." I smiled and concluded that the indoctrination was taking. In fact, Jim, I thought everything was going along fine until the college paper appeared the next day. One of the contributors wrote a piece about the new south and the poll tax.

Now there is no need to get you excited at this point about the poll tax. The whole thing, even in our deliberate American way, ought to be settled by the time you are in long pants. But it does so happen that your father is a good Southern liberal who knows what ought to be done about it. Well, he read the piece, and my heart sunk. He tossed the paper aside and allowed as how the South still didn't need Yankee suggestion. I somehow couldn't picture you in a pea green freshman cap at Dartmouth.

A couple of days later, we were walking through the Tower Room of Baker Library, I was proudly showing off that lovely building as a center of Dartmouth's intellectual life. Right in the middle of my spiel, we looked into one of the alcoves and there was a Dartmouth undergraduate sleeping soundly. The book had slipped to the floor and a cigarette was slowly burning itself out. A fine portrait of the hollow eyed scholar. This, I thought, finishes you and Dartmouth before you ever began. I stole a look at your father. He looked down upon the sleeping student and smiled. He tentatively felt the softness of the chair, looked at the book-filled cases and the smoldering fire. After a minute he said: "I think this is the place for Jim."

The very next day Lt. (j.g.) Chambers and myself presented ourselves in the office of Dean Strong and in a simple, quiet ceremony, entered you for the class of 1963. Your father and I, believing strongly in you and the future, went down to the Paddock and toasted you in beer.

Tomorrow (great day), we get paid. I'm going to send a small but sound contribution to this year's Alumni Fund in both our names. This year, Dartmouth men in all parts of the world, in places with long and strange names, wherever the Army and Navy have taken them—are all sending in something just to be sure that Dartmouth will be here when you're ready for Dartmouth. That is what we call the Dartmouth brotherhood and I welcome you into it.

Give my kindest regards to your mother. It occurs to me that her opinion hasn't been invited in all this, but I do hope she

approves.

Your uncle in collegis,

Identifies Picture

To THE EDITOR: You have asked for identification of a photograph on page 30 of the May ALUMNI MAGAZINE. X expect you will hear from several who recall the event portrayed. It was a procession after a championship baseball game. I think the deciding game was with Williams. As I recall it, Ranney and O'Connor were our battery and O'Connor pitched a no-hit game. Not a man got to second. In the seventh inning the coach for the parade came on to the campus, so confident were we that the game would be won. In the photo on the left, I think I recognize Archie Ranney at the plate.

Manchester. Vt.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

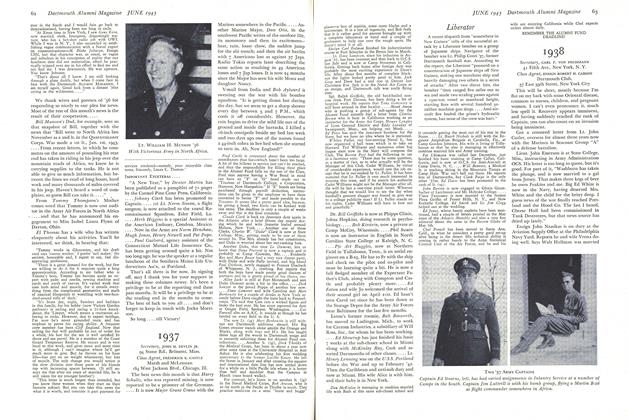

Article'Round the Girdled Earth

June 1943 By Dick Paul '41 -

Article

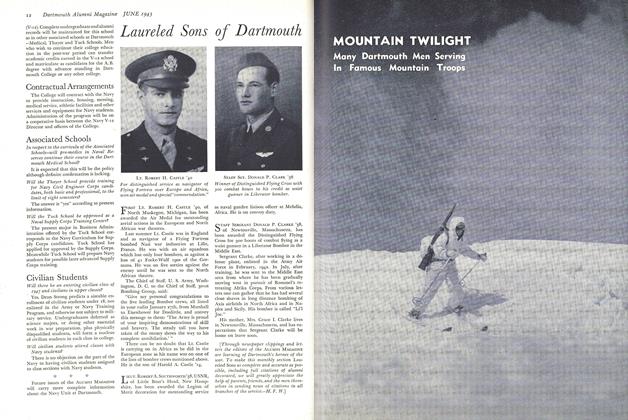

ArticleMOUNTAIN TWILIGHT

June 1943 By LT. CHARLES B. MCLANE,'41 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1937

June 1943 By JOHN H. DEVLIN JR., FREDERICK K. CASTLE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

June 1943 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Article

ArticleWar Training and Education

June 1943 -

Article

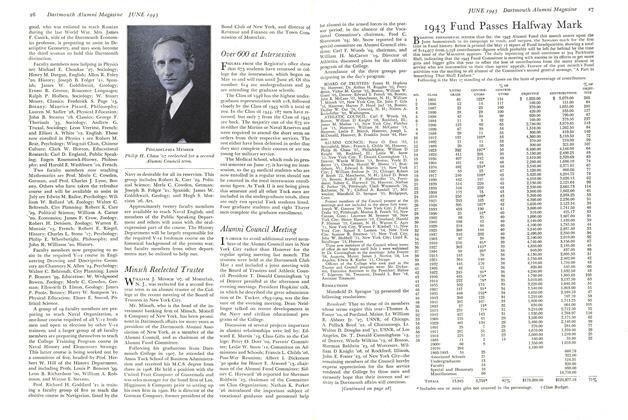

ArticleAlumni Council Meeting

June 1943