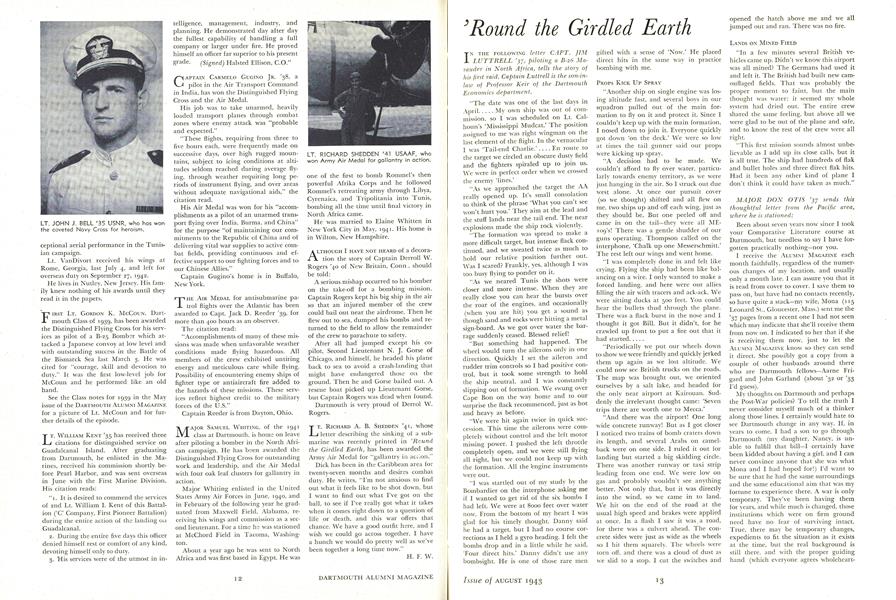

IN THE FOLLOWING letter CAPT. JIMLUTTRELL piloting a B-26 Marauder in North Africa, tells the story ofhis first raid. Captain Luttrell is the son-in-law of Professor Keir of the DartmouthEconomics department.

"The date was one of the last days in 4pril My own ship was out of commission, so I was scheduled on Lt. Calhoun's 'Mississippi Mudcat.' The position assigned to me was right wingman on the last element of the flight. In the vernacular I was 'Tail-end Charlie.' En route to the target we circled an obscure dusty field and the fighters spiraled up to join us. We were in perfect order when we crossed the enemy 'lines.'

"As we approached the target the AA really opened up. It's small consolation to think of the phrase 'What you can't see won't hurt you.' They aim at the lead and the stuff lands near the tail end. The near explosions made the ship rock violently.

"The formation was spread to make a more difficult target, but intense flack continued, and we sweated twice as much to hold our relative position further out. Was I scared? Frankly, yes, although I was too busy flying to ponder on it. "As we neared Tunis the shots were

closer and more intense. When they are really close you can hear the bursts over the roar of the engines, and occasionally (when you are hit) you get a sound as though sand and rocks were hitting a metal sign-board. As we got over water the barrage suddenly ceased. Blessed relief!

"But something had happened. The wheel would turn the ailerons only in one direction. Quickly I set the aileron and rudder trim controls so I had positive control, but it took some strength to hold the ship neutral, and I was constantly slipping out of formation. We swung over Cape Bon on the way home and to our surprise the flack recommenced, just as hot and heavy as before.

"We were hit again twice in quick succession. This time the ailerons were completely without control and the left motor missing power. I pushed the left throttle completely open, and we were still flying all right, but we could not keep up with the formation. All the "engine instruments were out.

"I was startled out of my study by the Bombardier on the interphone asking me if I wanted to get rid of the six bombs I had left. We were at 8000 feet over water now. From the bottom of my heart I was glad for his timely thought. Danny said he had a target, but I had no course corrections as I held a gyro heading. I felt the bombs drop and in a little while he said, 'Four direct hits.' Danny didn't use any bombsight. He is one of those rare men gifted with a sense of 'Now.' He placed direct hits in the same way in practice bombing with me.

PROPS KICK UP SPRAY

"Another ship on single engine was losing altitude fast, and several boys in our squadron pulled out of the main formation to fly on it and protect it. Since I couldn't keep up with the main formation, I nosed down to join it. Everyone quickly got down 'on the deck.' We were so low at times the tail gunner said our props were kicking up spray.

"A decision had to be made. We couldn't afford to fly over water, particularly towards enemy territory, as we were just hanging in the air. So I struck out due west alone. At once our pursuit cover (so we thought) shifted and all flew on me, two ships up and off each wing, just as they should be. But one peeled off and came in on the tail—they were all ME- 109's! There was a gentle shudder of our guns operating. Thompson called on the interphone, 'Chalk up one Messerschmitt.' The rest left our wings and went home.

"I was completely done in and felt like crying. Flying the ship had been like balancing on a wire. I only wanted to make a forced landing, and here were our allies filling the air with tracers and ack-ack. We were sitting ducks at 500 feet. You could hear the bullets thud through the plane. There was a flack burst in the nose and I thought it got Bill. But it didn't, for he crawled up front to put a fire out that it had started

"Periodically we put our wheels down to show we were friendly and quickly jerked them up again as we lost altitude. We could now see British trucks on the roads. The map was brought out, we oriented ourselves by a salt lake, and headed for the only near airport at Kairouan. Suddenly the irrelevant thought came: 'Seven trips there are worth one to Mecca.'

"And there was the airport! One long wide concrete runway! But as I got closer I noticed two trains of bomb craters down its length, and several Arabs on camelback were on one side. I ruled it out for landing but started a big skidding circle. There was another runway or taxi strip leading from one end. We were low on gas and probably wouldn't see anything better. Not only that, but it was directly into the wind, so we came in to land. We hit on the end of the road at the usual high speed and brakes were applied at once. In a flash I saw it was,a road, for there was a culvert ahead. The concrete sides were just as wide as the wheels so I hit them squarely. The wheels were torn off, and there was a cloud of dust as we slid to a stop. I cut the switches and opened the hatch above me and we all jumped out and ran. There was no fire.

LANDS ON MINED FIELD

"In a few minutes several British vehicles came up. Didn't we know this airport was all mined? The Germans had used it and left it. The British had built new camouflaged fields. That was probably the proper moment to faint, but the main thought was water: it seemed my whole system had dried out. The entire crew shared the same feeling, but above all we were glad to be out of the plane and safe, and to know the rest of the crew were all right.

"This first mission sounds almost unbelievable as I add up its close calls, but it is all true. The ship had hundreds of flak and bullet holes and three direct flak hits. Had it been any other kind of plane I don't think it could have taken as much."

MAJOR DON OTIS '57 sends thisthoughtful letter from the Pacific area,where he is stationed:

Been about seven years now since I took your Comparative Literature course at Dartmouth, but needless to say I have forgotten practically nothing—nor you.

I receive the ALUMNI MAGAZINE each month faithfully, regardless of the numerous changes of my location, and usually only a month late. I can assure you that it is read from cover to cover. I save them to pass on, but have had no contacts recently, so have quite a stack—my wife, Mona (115 Leonard St., Gloucester, Mass.) sent me the '37 Pages from a recent one I had not seen which may indicate that she'll receive them from now on. I indicated to her that if she is receiving them now, just to let the ALUMNI MAGAZINE know so they can send it direct. She possibly got a copy from a couple of other husbands around there who are Dartmouth fellows—Aarne Frigard and John Garland (about '32 or '33 I'd guess).

My thoughts on Dartmouth and perhaps the Post-War policies? To tell the truth I never consider myself much of a thinker along those lines. I certainly would hate to see Dartmouth change in any way. If, in years to come, I had a son to go through Dartmouth (my daughter, Nancy, is unable to fulfill that bill—l certainly have been kidded about having a girl, and I can never convince anyone that she was what Mona and I had hoped for!) I'd want to be sure that he had the same surroundings and the same educational aim that was my fortune to experience there. A war is only temporary. They've been having them for years, and while much is changed, those institutions which were on firm ground need have no fear of surviving intact. True, there may be temporary changes, expedients to fit the situation as it exists at the time, but the real background is still there, and with the proper guiding hand (which everyone agrees wholeheartedly is Pres. Hopkins) can be reemphasized at the proper time when outside furor settles down and allows a resumption of normal activities. Maybe there will be changes. Changes that cannot, even now, be seen. Changes that will improve the college, though I, for one, cannot imagine any such.

I am not a student in the true sense of the word concerning such topics as sociology, languages, psychology, art, music, etc. My main interests lie in math and physics—perhaps mainly because I have such constant need for these and because I see every day, the horrible floundering of students now face to face with a business that requires the exactitude of an exact science and not a lot of generalities concerning civilization, its past, present, and future, nor of the humanities.

A well-rounded individual must have these as well as the exact science training. A well-educated man needs both—and Dartmouth gives and requires both. I'd certainly not consider myself "well-rounded" though I had the background for it upon graduation in 1937. Since that time I've spent all my energies in learning the science of firing weapons of all types and having majored in physics and math my total mind remained bent in this direction and still is. It has gone so far now, that I tend to deprecate the social sciences as unnecessary though I know that that is entirely wrong—though nearly correct in this business of war (that is, out here). Therefore I consider myself as unfit to endeavor to state what course our post-war policies "should take. People have been trained (and I doubt if the best are in Washington now, unless additions have been made since the war) in this field and all I could state is what I myself could hope for—and that is exactly what anyone wants,—peace, a normal happy life, with my wife and baby, and a reasonable chance to make a decent living, and to do as I wish within the limitations of my job as an officer in the Marine Corps.

I have no cure-all for the world. I firmly believe that human nature will not be content to remain at peace forever. Every human has certain likes and dislikes which are governed mainly by his environment and to a lesser degree his heredity—like have nations a national characteristic. Either individuals or the mass of individuals (nations) can have conflicting ideas, which require settling. Most arguments between individuals and nations are settled verbally without resort to fists or weapons. However, there always has been, and probably always will be, arguments that can only be settled (but which never are settled to both parties—only the victor) by force of arms. What future scraps will be about, I nor anyone else can know, but after this war—lo years, 50 years, 100 years—sometime will come another scrap, because of some one's ambition or inordinate desire. I sincerely hope that such will not be the case—that an over-all council with a punch behind its decisions can be found to settle all disputes, and settle them sensibly that they may remain an over-all council and their decisions respected by every one.

Do I make myself clear? I'm not very good at anything of this type and probably will not be very productive of ideas. Possibly, generally speaking, Roosevelt's Four Freedoms covers it very well, though I'm afraid I agree very little with many other of his actions and words over the last 8 years. However, more people have agreed than the contrary and I could be wrong. I think that I feel too strongly the strikes, bad handling of food, and also almost all the other problems, the complexity of the alphabet soup and their conflicting fields of endeavor, and either a lack of power or unwillingness to use it to further the war aims. Despite all of this, we seem to be coming along quite well, though I often wonder if perhaps a little more efficiency wouldn't have shortened the period from the war until now, in terms of equal production, and thereby save a life or so which was wasted using inferior or inadequate equipment. I know much has been badly handled in the field, due to inexperience, but even with the muddling in the Capitol and in the field, we've done damn well, and as time and experience irons out many malfeasances, the Japs (I hardly even think of the Germans and Italians) will get the shock of their lives, surpassing even their present coma at our rapid bounce back from Pearl Harbor.

Well, my brain is exhausted and the results nil—I can now go back to dreaming of Mona and Nancy, dashing off a few rounds here and there, hugging old mother earth to dodge an occasional bomb, and feel sorry for myself on being so long away from the two gals that constitute what I call a home. 23 months now—and only 3 of these where a drink was available, and where there was even a woman to look at. And that, as I see it, is the background from my post-war desire for a happy, normal life with Mona and Nancy, forgetting all the rest. So long, Herb. Please write again. My best to all at Dartmouth.

LT. (j.g.) ALLEN '4O USNR, of the NavalAir Corps, writes the following fine letterconcerning service in the far North.

In various magazine and literary issues springing from the admirable hand of boys from the old college I have read much about Dartmouth Marines blasting Jap jungle monkeys out of fox-holes on Guadalcanal; or Hanover men pelting away at the red bull's eye in skies over Australia; or the Big Green running a mighty bleached and peaked lot of Jerries and Eyties through African deserts. But not one word about the boys fighting the war in our part of the world—Newfoundland, Labrador, Greenland and Iceland.

I have just returned from these parts and can truthfully say that the men up there are fighting a mighty grim battle. In northern latitudes your big enemy is the weather. Up there it might be easy pickings when you meet a German sub, but you always come out a poor second when you battle old man winter. Blizzards, hail, fog, rain, wind—take your pick. There is no joy-riding for two or three hours till you get over the target, and a little hot going, after which you lapse back into dreamland for the long trek home. In- stead you get eight solid hours of bouncing around from one snow squall to another, and after three or four hours on instruments without a peep from your radio, you become slightly uneasy. As a matter of fact your radio is no good when you have snow static, and whoever saw a day up there when it didn't snow?

COMPASS IS NO HELP

On getting farther north you find that 90 degrees of compass variation is nothing at all. You don't begin to worry until the compass starts spinning around like a pinwheel. That's the time when you start using your sun compass, but the guy who saw the sun last put it to bed in November. Now I'll admit the boys in the Pacific have a tough time on being forced down in the water—sun, thunderstorms, sharks and all that. But if you hit water up in the Northland, you automatically turn into an ice cube without having to bother about anything else.

Our ceilings of operation vary. Anything over 4.00 feet is mighty 0.K., and ceilings of 75 to 100 feet are plenty sufficient to slip into the base under. Most of the boys come poking along home on the wave tops. The other week one guy had to fly around the field over the water (the airfield is surrounded by water, field elevation 30 feet) for twenty minutes before he could stick his head up high enough to find out which runway to come in on. All his turns were skid turns because if he had banked, either his wing would have dropped in the water or else the cockpit would have gone up into the soup. Of course this fellow had some ceiling; others have had to come in on the beam at 50 feet over the field, then chop back on the guns and pray.

I have heard that the boys over in Africa have to put up with stiff winds, sandstorms and tornadoes. Up in Iceland and Green- land winds of 50 to 70 knots (wind force for hurricane is 75 knots) are everyday affairs. A couple of months ago a three plane section went out on patrol. They went straight out for two hours and straight back for nine hours. They were in sight of the coast of Greenland for five hours. The throttles were practically wide open and all guns, equipment and loose gear—everything almost including the second pilot was tossed overboard to lighten the load. When they finally got back in with about 75 gallons of gas left, they figured that they had been bucking a headwind of better than 90 knots. The highest wind recorded while I was up that way was 162 knots—no flying that day. Incidentally, have you ever seen dense fog in a 50 knot wind? Take a trip to Newfoundland.

Last but not least, we have the Green- land Ice Cap; and, brother, a man has never flown under tough conditions until he's flown over the Cap, where the ice is 8000 feet thick and the stuff has been known to build up to 1000 feet in two weeks. There are always a bunch of planes down on the Cap, and it takes an Arctic expedition to get you out. Last month a plane crash—landed 15 miles from the coast near the base, and it took three weeks to hike in to the crew on snow shoes. Patience and a good constitution are what you need to await rescue—if you are ever found. Usually, by the time you get out something has frozen or fallen off or else you have had to amputate a couple of your own feet with a carving knife.

I think somebody ought to tell Eddie Rickenbacker that there are a few of his Army boys who have been waiting on the Cap to be rescued for three months. They went down in November and they are still there—alive, too.

Well, that's all I can tell you about the war in the Northland. The next guy probably could tell you a lot more. At any rate it is said by a couple of old timers in the Navy and Coast Guard that flying on the average in the North Atlantic is as tough as in any other part of the world, and that includes the Aleutians. I, for one, believe them. So let's give three cheers for the boys who are still fighting away up there in the Arctic. But wherever you are, on whatever front—give 'em hell!

WRITTEN by Ist Lt. Ed McMillan Jr.'42, pilot of a Flying Fortress just twoweeks before the War Department reported him, first as missing in action, andlater as a prisoner held by the Germans inTunisia. His plane was on a bombing mission at the time of Marshal Rommel's firstheavy drive with his superior numbersagainst the American lines. The Americansyielded considerable ground at that timewhich was later recovered.

Ten thousand miles—Salina, Kansas, to Marakesh, French Morroco, without a single mishap or slip up. One chap landed on a small island, another went down in the Caribbean, several broke landing gears in these African fields and one missed here and went up to the Mediterranean before landing but we were on course all the way and had a highly successful ful trip.

Don't know just how much I should tell, but since Life and Time have outlined the course I'll mention the places they mention and omit one or two places that have just been opened up.

Left Florida two nights after I called you and had one of the most beautiful flights I have ever had over the blue, blue Carribbean. Came down through a partial over- cast and flew at 1,000 feet so as to see all the beautiful islands. The Haiti and Dominican Republic island mountains stood up for miles and then came Puerto Rico, so beautiful I can't describe it. Such foliage, everything green and growing and fresh. We circled for a long time over the island and its many beautiful bays. I want to go back there some day for a long visit. The island was like a green jewel lying in a cushion of bluest blue, the Caribbean. Leaving there we hit (after five hours flying) the north shore of Venezuela—just a mass of green foliage, trees, bushes and a gorgeous shoreline with mountains rising a few miles back. Eleven hours even on this flight and two of the eleven on instruments.

MANY MILES OVER JUNGLE

We followed the shoreline around to Trinidad and made our landing there. This was the first land we had touched since leaving Florida. Took off the next morning on the flight that took us over the Equator, across the hundred mile wide mouth of the Amazon and across hundreds of miles of jungle. Passed Devil's Island, off French Guiana, and flew around it at a couple of hundred feet to get a good look. A few hours out of Trinidad it became so hot that we flew with the windows open, but as we were flying through the front of a storm had to close them from time to time as we swept through a tropical squall. No scenery at all but mile after mile of steaming tropical jungle. Across the Equator and into Belem, Brazil. At Trinidad, being a British possession, we had had no language difficulty but here my smattering of Spanish came to good avail as the native tongue is Portuguese and we were able to order meals. At each field the quarters for transient officers were fair, the food unusually good with fruit predominating.

Next flight was short, about seven and one half hours to Natal, Brazil. Here after three days of heavy flying, I decided to lay over for a few days for a general overhaul of the ship and to rest the crew before the big jump. Spent one day on the ship and the next sightseeing in the town. A differ- ent Portuguese dialect was used here, but we got along. Bought a pair of half boots of fine soft leather for $4.50 that would have cost $12.00 in the States and they will come in handy. Natal is a rather dirty town (all the natives either Portuguese or Brazilians) with interesting winding streets and an endless supply of watch shops but little else. The Ford and Standard Oil signs that had met us everywhere were present here.

Got out the next morning at 2:30 on the long hop. Almost 2,000 miles to Africa. Everything went like a charm and the engines ran beautifully (I had had a bad leak plugged at Belem and checked at Natal), and in ten hours and forty-eight minutes we sighted land—very good time for the hop, but we had gone to 11,000 feet to catch the most favorable winds. The field was some minutes off as I had pur- posely tried to hit on one side of our des- tination so we could definitely turn left on the shore and hit it. First hour out had been on instruments but for the rest the sky was clear and we had no trouble lo- cating the field. In 11 hours and 40 minutes we had set the Fortress down on a wire mesh landing strip and were greeted by a swarm of native blacks who worked on the runway until a flare was fired to drive them off while our plane landed. Fortunately, we had no trouble over the ocean although right at the middle I could have sworn that every one of those four engines was throwing a gallon of oil a minute. Our radio was out but a fellow ahead had smashed his landing gear so we took his radio and got away the next morning.

The blacks at... . were blacker than anything I have seen in my life. All wore ridiculous hats and long robes or shorts. We took a picture of several under the plane. I hope it turns out well. Quarters here were tents with rope cots and blankets, nothing else. According to the records, crews that landed here have at times had to chase the baboons from their ships when loading in the early morning. Fortunately, we had no such experience. We were, however, right in the midst of the African jungle. Out of there the next morning and over a stretch of more than a thousand miles above the Spanish Sahara, seeing but two towns during that whole time. No railroads, roads or anything but a few caravan trails over the sands. One of the two towns had a huge walled structure that looked like a Marahaja's palace with imposing roof and towers. Then in the distance, the great snow covered Atlas Mountains rising at the end of the great desert, through a pass between two 14,000 foot mountains and over a bunch of abandoned towns looking like honeycombs from above, all walled with square structures within, then down into the fertile soil of the other side to the walled city of Marakesh with its many towers, in seven and three quarters hours.

ROOM WITH BATH

I wrote Betty a long description of Marakesh and she will mail it on to you. We are quartered here in one of the most ornate hotels I have ever seen with a huge white dining room with a tremendous set of glass doors opening out onto beautiful gardens. Ours is a double room with bath and a balcony looking over the gardens to the distant rise of the white Atlas Mountains. The hotel, La Mamonnica, was one of the show places of Morocco before the war and we are enjoying its luxury (still run by its private management) while awaiting orders as to where to report.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH WAR DIRECTORY

August 1943 -

Article

ArticleOpportunity for Improvability

August 1943 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1934

August 1943 By JOHN W. KNIBBS III -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

August 1943 By ERNEST H. EARLEY -

Class Notes

Class Notes1937

August 1943 By JOHN H. DEVLIN JR. -

Article

ArticleLaureled Sons of Dartmouth

August 1943 By H. F. W

Lettter from the Editor

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

MAY, 1928 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

November 1928 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

MAY 1930 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorPresident Hopkins on Prohibition

February, 1931 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the Editor'Round the Girdled Earth

May 1944 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the Editor'Round the Girdled Earth

February 1945 By H. F. W.