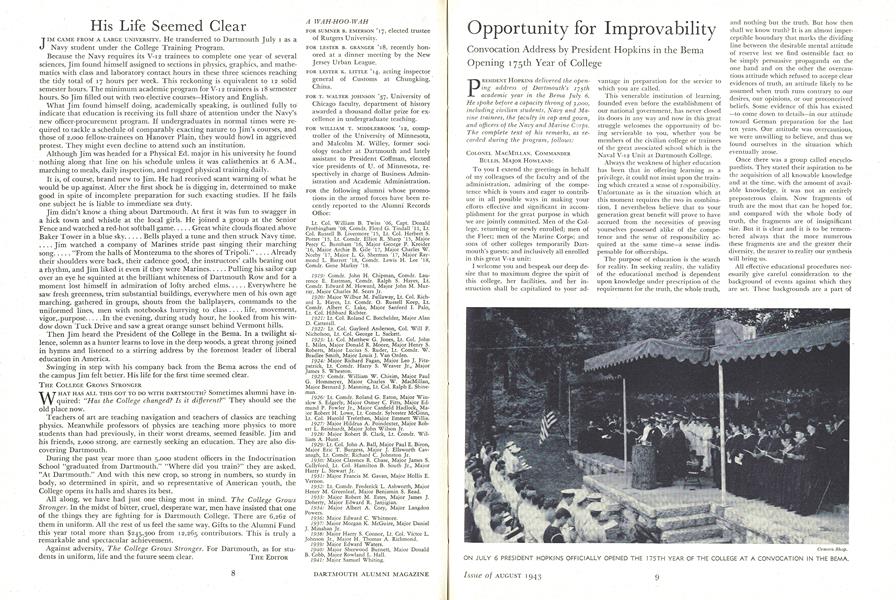

Convocation Address by President Hopkins in the Bema Opening 175th Year of College

PRESIDENT HOPKINS delivered the opening address of Dartmouth's 175thacademic year in the Bema July 6.He spoke before a capacity throng of 3,000,including civilian students, Navy and Marine trainees, the faculty in cap and gown,and officers of the Navy and Marine Corps.The complete text of his remarks, as recorded during the program, follows:

COLONEL MACMILLAN, COMMANDER Bums, MAJOR HOWLAND:

To you I extend the greetings in behalf of my colleagues of the faculty and of the administration, admiring of the competence which is yours and eager to contribute in all possible ways in making your efforts effective and significant in accomplishment for the great purpose in which we are jointly committed. Men of the College, returning or newly enrolled; men of the Fleet; men of the Marine Corps; and sons of other colleges temporarily Dartmouth's guests; and inclusively all enrolled in this great V-12 unit:

I welcome you and bespeak our deep desire that to maximum degree the spirit of this college, her facilities, and her in- struction shall be capitalized to your advantage in preparation for the service to which you are called.

This venerable institution of learning, founded even before the establishment of our national government, has never closed its doors in any way and now in this great struggle welcomes the opportunity of being serviceable to you, whether you be members of the civilian college or trainees of the great associated school which is the Naval V-12 Unit at Dartmouth College.

Always the weakness of higher education has been that in offering learning as a privilege, it could not insist upon the training which created a sense of responsibility. Unfortunate as is the situation which at this moment requires the two in combination, I nevertheless believe that to your generation great benefit will prove to have accrued from the necessities of proving yourselves possessed alike of the competence and the sense of responsibility acquired at the same time—a sense indispensable for officerships.

The purpose of education is the search for reality. In seeking reality, the validity of the educational method is dependent upon knowledge under prescription of the requirement for the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth. But how then shall we know truth? It is an almost imperceptible boundary that marks the dividing line between the desirable mental attitude o£ reserve lest we find ostensible fact to be simply persuasive propaganda on the one hand and on the other the overcautious attitude which refused to accept-clear evidences of truth, an attitude likely to be assumed when truth runs contrary to our

desires, our opinions, or our preconceived beliefs. Some evidence of this has existed —to come down to details—in our attitude toward German preparation for the last ten years. Our attitude was overcautious, we were unwilling to believe, and thus we found ourselves in the situation which eventually arose.

Once there was a group called encyclopaedists. They stated their aspiration to be the acquisition of all knowable knowledge and at the time, with the amount of available knowledge, it was not an entirely preposterous claim. Now fragments of truth are the most that can be hoped for, and compared with the whole body of truth, the fragments are of insignificant size. But it is clear and it is to be remembered always that the more numerous these fragments are and the greater their diversity, the nearer to reality our synthesis will bring us.

All effective educational procedures necessarily give careful consideration to the background of events against which they are set. These backgrounds are a part of the synthesis which we eventually must achieve. Our background today is war, and a war in which, among other things, determination will be made as to whether untrammeled opportunities for education are to be available in the future anywhere in the world, as for long years since even before our government was established, aspiration has existed to make them available in the United States.

Walking down Pennsylvania Avenue past the great building which is the Archives of the United States, one sees a deep inscription on the corner- stone, which reads: "What is past is prologue." Let us for a moment consider some of the more recent lines of this prologue of our times to which we give attention today—a prologue suggestive of the drama yet to come. I am not one who believes that such measure of success as we have had in girding ourselves for struggle up to the present time is indicative of the fact that there never was anything wrong with us. The fact that under the spiritual surgery of the war we have become socially convalescent is no reason for an assumption that for past decades civilization has not been seriously ill.

And how does this apply to the present situation? Raymond Gram Swing last week quoted a propaganda broadcast to the German people by a Nazi leader to the effect that if the Nazis would hold steadfastly for a time, they would find that there was little to fear from the United States, since, according to this German broadcaster, the people of the United States were willing to wage nothing more than a comfortable war and that when they found their war to involve real and widespread self- sacrifice and hardship, internal resistance within the United States would break down morale, create internal dissension, and completely neutralize our contribution to the war.

This I think we may agree is an exaggeration of the extent to which our morale as a people has become impaired amid the luxuries, comforts, and conveniences of modern life, but on the other hand on that particular night the assertion did not seem ,so completely improbable as we might have argued it to be before the epidemic of strikes, race riots, and the widespread grumblings against submitting to anything in the way of a petty sacrifice. Certainly we have not been free from the deterio- rating tendencies and the internal corrosion of something indispensable which seems eventually to disappear from advancing civilizations. Certainly in the past these have been overcome when at last physical environment having been conquered and necessity for physical struggle having been largely decreased, the beneficiaries of civilization have gradually sloughed off any sense of responsibility for cultivating and maintaining those qualities the striving for which had previously made them great. Brooks Adams, in his book "The Law of Civilization and Decay," asserts that it requires but three generations entirely to transform the characteristics of a civilization. Certainly those qualities of fortitude, fervor, and faith which were so largely significant in the establishment of this government and which earlier than that led to the establishment o£ American colleges and which still earlier brought the Pilgrims and others to this country in search of a freedom that they could not find at home—certainly those qualities, and I repeat them, fortitude, fervor, and faith, have been conspicuous by their absence within the recent decades.

We have chosen, as a matter of fact, to ignore certain very tangible truths, such as that safety first never bred a generation of heroic mold, or that security is no sufficient ideal as a challenge to spiritual or moral fervor; or that bounty is no adequate substitute for opportunity; or that though men were created free and have an equal right to opportunity, they do not have an equal right to the rewards of opportunity excepting as they win these; or most important, that "life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness" is something quite different from life, liberty, and the pursuit of self-indulgence.

To those who would say that there is no reason for regretful introspection in regard to the past, since America can always pull itself together to meet any hazard, let us not forget that we have escaped defeat and economic subjugation, at least, to totalitarianism by nothing short of a series of miracles. First there was the in- explicable failure of the Germans to follow up Dunkirk, when Britain was help- less; second, there was the abandonment of the German blitz just about as it was to become successful; third, there was the extraordinary blunder of the Nazi attack upon Russia; fourth, there was the psychological fallacy of the Axis in the attack upon Pearl Harbor, without which unity in this country would have been long delayed; and fifth, there was again the in- explicable withdrawal of the Japanese forces, with Hawaii prostrate and the Pacific Coast without adequate defenses.

Certainly we must assume that there is some higher power that watches over a democracy that has again and again been saved, as America has been saved, by such circumstances which could not have been foreseen or expected.

Lack o£ understanding and our tragic delay are due probably to the complexity of modern life which conceals relation- ship between cause and effect. I doubt if there is any very general understanding of the effect of the change in the type of immigration into the United States operative for the last half century. Up to 1890 or thereabouts, the immigration was from northern Europe; Amsterdam was the center of that immigration. The immigration, in other words, was from countries which had been used to law and order, in which government was a protection and in which law was a safeguard. And then due to various causes, among which was the exploitation of industry, the promotion of transatlantic lines, and various other factors, the center of immigration shifted slowly and diagonally down southeast across Europe until twenty-five years later it was in Budapest. The significance of this was that the peoples of the more recent immigration have been peoples to whom law has meant oppression and to whom government has meant tyranny. And the melting pot could not work rapidly enough to absorb all of these and to make our government actually a unity. But nevertheless if there had been understanding of the significance of cause and effect, something might have been done about it. Closely related was the shift within our time from a rural to an urban civilization. Only a few years ago that took place, and men in rural communities have a keener knowledge, a keener interest, and a keener understanding in regard to the relations between cause and effect than is possible to those born and bred in cities.

I take a single example. Within my own time I have known people in the northern part of New England, not more than fifty or seventy miles from this spot, who came from self-sufficient farms. One of my most intimate friends was brought up on such a farm. He rose at four o'clock in the morning, he chopped the wood, he did the chores, he went to school, and he came back and repeated the chores. He knew just how much labor was involved in creating the warmth in winter that made his home comfortable. Moreover, he either participated in or saw the action by which the wool was sheared which was spun into yarn which was woven into cloth from which the family clothes were fashioned. He had a part in or was an observer of the processes by which the tallow was run from which the candles were made from which the light was given. So of the food he ate. He knew and the men of his generation and men living under those conditions knew the relationship of cause and effect and governed their thinking and their actions accordingly.

More recently a great electrical development has taken place in that same territory—some of you may know it—the Fifteen Mile Falls development. It required years of planning on the part of the engineers of a great electric company; it required months to manufacture the apparatus; it required digging deep chambers for apparatus; it required operating skill and management. Then wires were strung across New England. Curious one day, on my way to Boston, I stopped on the Salisbury cut off and saw some men running wire across a field. I went out and asked what they were doing. The answer was that they were stringing wire. I said yes, I understood that but I asked, "Where does the wire come from?" Again the answer, with expletives, how did they know? "Well, where was it going to?" Again, how did they know? There was absolutely no consciousness probably on the part of any considerable number of the thousands of men who had to do with that development as to what any other part of the development was or what its impact upon the society of the time was.

Thinking along this line I was in the house of one of my friends one morning subsequently and knowing that the electricity in that part of Boston came from the Fifteen Mile Falls, I said to the son twelve years old, "Where does the light come from?" And he pointed to the switch on the wall, and said, "From there."

And that parable, which is absolutely true, is not at all exaggerated in regard to our recognition of cause and effect in many an incident of our lives and in regard to many a problem which is troubling us at the present time. There is little knowledge under present-day circumstances of the amount of planning and of the amount of labor that go into affording us the conveniences and the luxuries of a life to which we have become accustomed and about the loss of which we bitterly complain when deprived of some small portion of them.

Horace Mann said more than a century ago something to the effect that his belief in education was because he believed in the improvability of man. Well perhaps a century is too short a time to determine whether the line of direction is towards progress or retrogression, but I doubt very greatly if the improvability of man has been very greatly marked in the century past. Gentlemen, the task you have under- taken is to preserve for a free people the opportunity for improvability. That improvability is dependent upon the desire for learning which you will allow to possess you. Eventually this war will be over and you will have long lives to live in restoring the paths in which humanity shall walk. When that time comes and when freed from the impact of some contemporary conditions, I want you to think of educa- tion in other ways, in itemizations such as Francis Bacon laid down years ago, when he said:

"Men have entered into a desire of learning and knowledge .... seldom sincerely to give a true account of their gift of reason, to the benefit and use of men: as if there were sought in knowledge a couch, whereupon to rest a searching and restless spirit; or a terrace, for a wandering and variable mind to walk up and down with a fair prospect; or a tower of state, for a proud mind to raise itself upon; or a fort or commanding ground, for strife and contention; or a shop, for profit, or sale; and not a rich storehouse, for the glory of the Creator, and the relief of man's estate."

Gentlemen, for a few months you are here in preparation for war. Due to a wise and liberal policy—a Government policy —you are enabled at the same time to seek learning and to acquire knowledge. May God give you the desire to get it and may He give us the ability to give it!

Camera Shop. ON JULY 6 PRESIDENT HOPKINS OFFICIALLY OPENED THE 175TH YEAR OF THE COLLEGE AT A CONVOCATION IN THE BEMA.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH WAR DIRECTORY

August 1943 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the Editor'Round the Girdled Earth

August 1943 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1934

August 1943 By JOHN W. KNIBBS III -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

August 1943 By ERNEST H. EARLEY -

Class Notes

Class Notes1937

August 1943 By JOHN H. DEVLIN JR. -

Article

ArticleLaureled Sons of Dartmouth

August 1943 By H. F. W

Article

-

Article

ArticlePRESIDENT NICHOLS AMONG THE ALUMNI

March, 1914 -

Article

ArticlePROPOSED CHANGES IN THE CONSTITUTIONS OF THE ALUMNI ASSOCIATION AND THE ALUMNI COUNCIL

May, 1922 -

Article

ArticleDefense, Policy

January 1941 -

Article

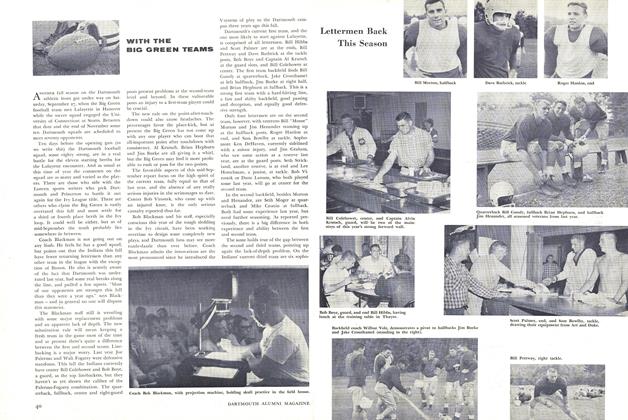

ArticleLettermen Back This Season

OCTOBER 1958 -

Article

ArticleGo Figure!

May/June 2010 -

Article

ArticleJohn Wesley Young

MARCH 1932 By H. E. B.