A Double View

To THE EDITOR:

Being in rather a unique position, I was interested in "Who's Being Liberal?" in the March Gradus Ad Parnassum. In my one year at Dartmouth, I became deeply attached to the entire atmosphere surrounding Hanover. The next two years, however, I attended St. John's College at Annapolis and had ample opportunity to compare the relative merits of each college.

While both are colleges of Liberal Arts, there is one noticeable distinction. In my stay at St. John's, I was aware of a sense of correlation in my studies. Having left one class and gone to another, I could not put the first subject out of my mind, because it still played a part in the second. This was a constant feature and one which eventually created a tendency to think always in terms of analogy and association. Thus, while we may not know something we encounter, we are able to figure it out more quickly by associating it with something with which we are familiar—and the program at St. John's is sufficiently varied and intensive to give familiarity with many of the universals of which the particulars are often less familiar.

This, I found, was the great distinction between the two colleges, for at Dartmouth, I did not experience this method of association. In going from philosophy to English, or from social science to French, I had to put the former out of my mind to concentrate on the latter, thus missing the infinite bridge of thought in between.

As far as President Hutchins' accusation that the social side of college is overshadowing the intellectual side, do not be too alarmed—perhaps at St. John's discussions on universals and their high-planed particulars were more frequent than at Dartmouth, but the difference did not overwhelm me. I do believe that correlation of thought was less at Dartmouth and should be the responsibility of the college as well as the student, who is not always the best one to choose among subjects often new and unknown to him.

Fort Leonard Wood, Mo.

St. John's '44.

Postwar Service

To THE EDITOR

To what extent will national military service be carried out in postwar years, and how will it be correlated with the prewar type of educational system? These are questions which I have pondered and discussed at length with other officers. It is a subject I would like to see aired in the columns of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE. In order to stimulate others' thinking in hopes that more and better ideas will result, I am presenting a few ideas on the subject.

Working on the premise that national compulsory military training of all fit males is a necessary and sound insurance for our nation's welfare, and that with the camps, equipment, and trained personnel that our armed forces will have at the conclusion of the war, it would be foolhardy to ignore these facilities and not have a large scale continuous training program for the next decade at least. Also, I believe that we are all agreed that we want to maintain our educational system, particularly the colleges and universities, operating on much the same basis as in the past, with little or no interference by the military program.

The following outline is presented as one possible answer to this problem:

Each year all fit male citizens reaching the age of eighteen during that year will begin in the months of June, July, and August, one year of basic military, naval, or marine training. They will be selected, examined, and enlisted under a system similar to the present selective service. The time of year for induction will enable high school seniors to graduate.

They will spend one year in training camps and organized units, squadrons, and fleets, undergoing basic and specialized training.

Following this year of service there will be many alternatives for those being released (during the summer months): 1. They can return to civilian life as enlisted reserves.

2. They can enlist in the regular services for further training and advancement thereby providing a cadre of regular enlisted specialists and NCO's.

3. Some can be selected and take competitive exams for entrance to the U. S. Military and Naval Academies.

4. Some can be selected to go to certain civilian colleges, particularly the technical ones, to attend on a basis similar to the V-12 of today. They will be sent at government expense with the stipulation that upon graduation they will take an additional year of military or naval service in a Reserve Officers School and on active duty. Certain outstanding officers of this group, who desire, may be selected to stay in the service as regular officers. The others may return to civilian life as reserve officers with opportunities for active duty periods and military schooling from time to time.

The Navy V-12 Program and the Army ASTP are very democratic methods of affording opportunities for higher education to men who otherwise would be unable to enjoy these advantages at their own expense. These programs should be continued after the war on a modified scale. It is little to ask of these men that in return for their education they give the government an additional year of their services and maintain the status of a reserve officer.

This program should in no way entail any great modification of the prewar ROTC and NROTC units that some schools maintained. It should merely be a supplement to this source of trained men. The Air Forces' needs could be tied in also, merely requiring longer periods of training and duty, as they always have anyway.

The eighteenth year is the best time to take a man from his schooling because the average college undergraduate at that age tends to be immature and doesn't fully appreciate his exposure to higher learning. Whereas if men were to enter college at nineteen or twenty after a year in the armed service, they would not only have lost some of their provincialism but would be more fit for advanced education, mentally, physically, and socially.

This war is proving the soundness of our system of acquiring officers from all sources; the ranks, the academies, and the civilian colleges. We should continue the system on a scale that will keep us well provided with officers, so that never again will our armed forces face the growing pains and strains this war has caused.

Dartmouth's association with the Navy and Marine Corps is proof enough that the civilian colleges and the military can work together to their mutual benefit, and the men of Dartmouth in uniform can testify to the benefits and need for military training of all men.

Major, USMC.

C/o Fleet Post OfficeSan Francisco, Calif.

The editors are indebted to Major Donovan for this thought-provoking communication from the South Pacific. We share his hope that our columns may be utilized to air alumni opinion on this subject, as on other topics of Dartmouth's relation to the postwar world, and letters from our readers will be welcomed.

In its earliest days, characterized by one historian as a period of "chronic impecuniosity," Dartmouth College sometimes nof only skipped the President's salary but borrowed money from him to make both ends meet. Fortunately, John Wheelock, son of Dartmouth's founder and second president of the college, had some independent means besides his yearly salary, which in 1814 amounted to $912.00.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

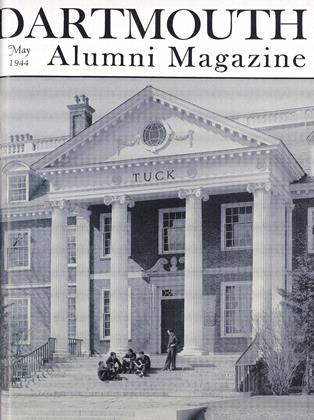

ArticleTHE GREEN FLIES HIGH

May 1944 By ARTHUR SAMPSON -

Class Notes

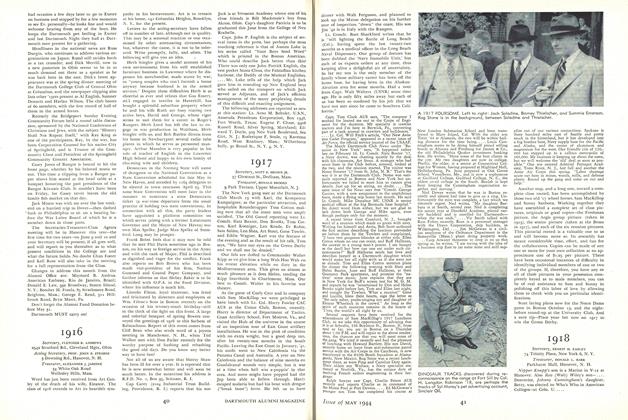

Class Notes1914

May 1944 By DR. WALLACE H. DRAKE, JOHN F. CONNERS -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the Editor'Round the Girdled Earth

May 1944 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917

May 1944 By MOTT D. BROWN JR., DONALD BROOKS -

Class Notes

Class Notes1934

May 1944 By WILLIAM C. EMBRY -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

May 1944 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR