Letters from Dartmouth Men in the Armed Forces

THIS LETTER FROM Italy from awriter who should perhaps at this time remain anonymous is one of the most pertinent that I have seen and, I am very gladto print it in these columns. It was writtenin January, 1944.

Your letter was very happily received a few days after Christmas when I was still back in North Africa. But now I am located in Italy and things have changed considerably. My morale has climbed since coming over here because now the reasons for things are apparent. I must perforce be vague about most everything as censorship is much stricter here and for obvious reasons. But the land of the noble Roman —not so long ago enemy territory—is interesting—sometimes too damn much that way and our time is well occupied.

Our group is split up now, i.e. the bunch from the old outfit—some of us fighting already, and others of us about to fight. So there isn't much time for sightseeing—ruins both ancient and modern. (The latter outweigh the former I believe.) But there is a lot of wine that tastes like apple cider and sells for outrageous prices and some horrible cognac that settles down on the mind like dope and sets it running in strange and devious channels

Italian women are plentiful, dirty, and a few are pretty. Nurses are, of course, available for the combat soldiers to wolf from the medics, and sunshine—as rare as whiskey over here—is glorious when you get it. Usually there is rain, sleet, snow, mud, cold, and once in a while ice on the puddles. Water over everything is the usual accompanied by a wet miserable cold that is unlike anything I have ever felt. Talk about mountains! The mountains here are the toughest things I have ever seen. They aren't high in altitude as they start at sea level, but they go straight up—jagged and as steep as any of the cliffs around our old camp. Figure for yourself how you would attack those cliffs at home and you get an idea—only an idea of why it has taken our armies so long here. The more I think of our old outfit, the more I realize that the only thing you have is better transportation for this type of country. What you need is tough soldiers mentally and physically equipped to do the job. If they only prepared the men mentally for the job instead of telling them how good they were all the time, there would be a lot less cases of "shell shock." No man is good when he stands in front of a well-dug-in machine gun. Better to tell them they are pretty good but never good enough until they are perfect. You can never win a war pampering men. I was a great offender in this with my men in the States. You became known as a "good guy," but too many of them are dead already. I didn't intend to talk shop, but all this slipped in somehow. As you get closer to die front, you lose the GI stuff, but immediate obedience to orders is much more important. That is why you should insist on the "chicken" while there.

As much as I dislike the German system, their military discipline is causing us a lot of casualties, and it is because we officers never insisted on complete discipline in the States. Likewise, the British. They are far stricter than we and that is why they are such damn good fighters.

Also, fire at your men with everything you have from every direction you can and in all circumstances. Confuse them as much as possible—teach them to locate weapons by the sound. Teach them to estimate the range to a weapon by the sound of the crack of the bullet close by and the thump of the weapon. Put them through fire at night as well as during the day. Show them the muzzle blast of a M-G at night. Show them how and make them crawl for several hundred yards a day. Give them bayonet till they puke and then give them some more. When they know all this, when they know their weapons, cold, when they know what a near miss is with small arms, when they know how close they can advance under their own friendly fire before they lift it, when they have run through platoon problems lasting several days and fired their weapons under every conditionthen you will have a pretty good outfit, halfway seasoned. They baby the soldiers with too much of the "Kid in Upper 4" stuff. What kind of a front line soldier do you think that sobbing kid would make? When men start feeling sorry for themselves over here, they are worse than useless. First they are no good as fighters and second, they have to be fed and supplied. My point is that if a man is mentally prepared for this, he isn't going to feel sorry for himself when he gets into it. Naturally, what I have said goes for officers as well, and if an officer doesn't feel up to it, he ought to turn in his bars and let someone who can "take it" and "give out" wear them.

MAJOR HUDSON E. BRIDGE '40,USMCR, wrote the following letter to hisparents who live in Walpole, New Hampshire. It is an unusually interesting letterand I am glad of the opportunity to printit here.

At last you can say you have a son who has assaulted the Japs on their own territory. Yep, I was in on the Eniwetok affair and came through without a scratch.

On February 19, we landed on Engebi Island and took it in a day. Herded aboard ship again and on the 22d took the quite tough Parry Island and finished that up in short order also. However, it wasn't as easy as it sounds and when I look back on it I often wonder how I got through it.

Although I can't tell you how we landed, or the tactics used I can attempt to describe the way I felt through the whole thing. To start off with we have trained so much along these lines that we all knew our jobs perfectly and it seems normal going in. Before going in you have to get yourself in the proper frame of mind about getting wounded or killed. By doing so you eliminate any fear that these two factors might arouse. With this fear eliminated the operation doesn't bother you at all.

Naturally we knew about the operation well in advance and had occasion to study it from every possible angle. The night before the first attack was just like any other night. I thought little about it but it was in the subconscious for I dreamed about it off and on during the night but lost no sleep. I don't think I was any more excited than before a football game or a tennis match. In the morning ate a hasty breakfast, and then set about methodically loading my weapon and testing its firing devices. Then studied my map for a short period and ran over a few Jap phrases that might be of value to trick the little so and so into the open.

Going into the beach seems like any practice landing except for the bullet holes appearing in our boat. On the way in I gave the men last-minute instructions as to who would cover the right and left and how to fan out. Glanced at my watch to see how the time schedule was working out and noted the steadiness of my hands. Looked around at the men to see how they were taking it and they all looked pretty good; some of them still smoking a last cigarette. Then I cocked my piece and braced myself for the hitting of the beach.

As soon as we grated on the sand out I jumped with the men behind me. I fired a couple of test rounds into the sand to make sure the piece would work. Rifles were cracking all around us and they weren't friendly either. However, the steepness of the beach provided us with sufficient cover to move on up forward. There was a Jap machine gun up to our right flank and it was blazing away and kicking up sand all around us. We continued to push on until the island was taken.

The second landing was much the same only you felt more like your luck might have run out in the first one. The resistance was a little tougher and there was more firing as we landed but it didn't seem to bother. All the men want is a little organization and an objective and they're off with grim determination. While organizing the men the Jap fire snaps all around and kicks the sand one step in front of you, but for some reason it doesn't register. You're more interested in getting the show moving. You move up to a Marine, give him a big slap on the back and a smile to show him everything's O.K. and point out his objective and he's up and away. nru „r „n • „ „• _._T 1

The toughest part of all is at night when those little fellas try to sneak around in behind you. Everyone's got to stay awake and keep the eyes open. Believe me its a long twelve hours from sunset to sunrise, especially after going hard all day. We were truly tired after the second landing as you can well imagine.

In the two operations I lost a total of 20 pounds cutting me down to a slim 185. Of course I never eat in the field, too exhausted I guess, and that plus the running around results in a good work out.

CAPTAIN GEORGE W. RAND '19,USAAF, writes a fine letter from NewGuinea where he has spent the last ninemonths.

Received your V mail the other day and was very glad to hear from you. Bill Embree forwards the "Bulletins" to me regularly, and with letters from the family, I keep pretty well posted on Hanover and the College. Have run across very few Dartmouth men in my travels. Saw Art Smith and George Scott at our previous base.

Combat intelligence work with a fighter squadron, and latterly at group headquarters has, of course, been the most interesting experience of my life, and despite all the discomforts of life in the tropics, and there are plenty of these, I wouldn't have missed it. As you may know, our job is to prepare maps, collect all the information we can get through various sources regarding the enemy air strength, disposition, tactics, new planes, brief and interrogate the pilots, send in reports of their missions to higher headquarters, and act as a clearing house for all information on the war both in this theater and all the others. At this particular advanced base, I have been doing quite a bit of liaison work with the Navy and the Army Ground Forces and this of course adds to the interest, as I get a picture of the whole show, and what is to come.

Our group is flying P47S, and we have made a remarkable record in our operations so far, with 175 confirmed victories over the Nips, as against one of our pilots lost, and two missing (probably lost) due to enemy action. I doubt if any group anywhere can touch it. Our ex-C.O. (Col.) Neel Kearby, has 21 of the louses to his credit, getting 6 in one mission (you may have read about him) and was recently awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor by General Mac Arthur, and understand that we are in line for a group citation as well. Needless to say, we are very proud of the boys.

We all feel that at last we are making some progress in this theater. I doubt if anyone not on the ground can conceive of the difficulties under which we all operate here,—the continuous, terrific heat, the bugs, mosquitoes (our greatest trial) and other forms of insect life peculiar to New Guinea, the tremendous distances involving a supply problem of vast proportions, and the undeveloped state of the terrain forces us to start from scratch in every move we make, which means hard work with no let-up. Besides, we get occasional bombings, mostly of the "scalded cat" variety, as they say in dear old England, and possibly made to "save face" after our bombers have given them a good blasting. However, I can't say that I like the sound of a falling bomb any better now than I did the sound of an approaching shell twenty-six years ago in la belle France. AH of which brings me to the conclusion that this is definitely my last war, although ray speed in hitting the dirt or a slit trench has not been impaired (much) by the passrag years.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHE GREEN FLIES HIGH

May 1944 By ARTHUR SAMPSON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1914

May 1944 By DR. WALLACE H. DRAKE, JOHN F. CONNERS -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917

May 1944 By MOTT D. BROWN JR., DONALD BROOKS -

Class Notes

Class Notes1934

May 1944 By WILLIAM C. EMBRY -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

May 1944 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1933

May 1944 By GEORGE F. THERIAULT, LEE W. ECKELS

Lettter from the Editor

-

Lettter from the Editor

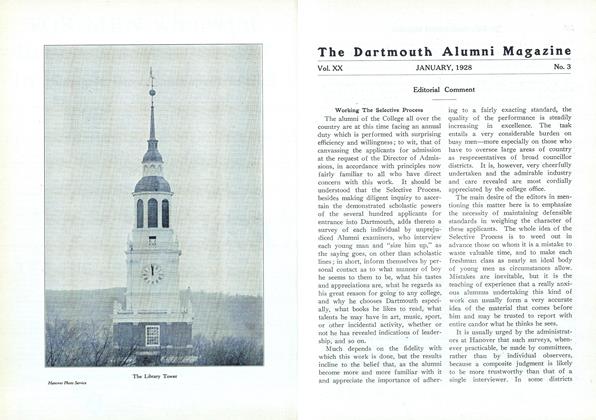

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

JANUARY, 1928 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

MARCH 1930 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

MARCH 1932 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorLetters from Dartmouth Men in the Armed Forces

November 1943 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorDateline Hanover

MARCH • 1986 By Douglas Freewood -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorWhat's a Humane Letter?

February 1939 By JOHN PALMER GAVIT