Letters from Dartmouth Men in the Armed Forces

FIRST LIEUTENANT HAROLD L.BOND '

'42, (see Laureled Sons for this issue) has written one of the finest war letters I have ever seen and I am proud toreproduce it here in full. It comes fromthe Italian front.

I don't know if you remember the warm fall evening when I was at Hanover to say hello and goodbye to Dartmouth before going overseas, but I met you on the steps of the Inn. You asked me to write and so I will. I have thought of writing you many times before this but decided to wait until I knew a little better what I wanted to say. That day never seems to come so I think I'll write now.

Since that short but deeply satisfying visit much has happened to me. A great deal of it has been unpleasant, some of it fun, and all of it in one way or another an experience that I don't think I regret. After making the usual rounds of North Africa I hit Italy in January and was almost immediately sent to the front for duty. I got there in time to take part in an attempted river crossing near .

That first battle, later experience has taught me, was about as bitter and as tough a fight as a man could ask for. In any case it certainly got me started in a big way. I led an Infantry mortar platoon (81 mm.) and after the attempt at the river we went to Cassino itself to fight. The snow, rain, almost unbelievable mud and the intense cold made it bad enough, but on top of that the Germans had everything in their favor. They had the high ground and could look down our throats. We did our best but you know the rest of the story. We didn't take the town then and finally were relieved—battered, bruised, and discouraged. Since that time we had more fighting and better fighting in recent weeks. You have read the news on this score, and I think you can imagine our feelings as we drove through the deserted streets of the eternal city. The road to Rome had been bitter all the way until the very end. Even at the gates of the city we had a hell of a fight. I had been happy at the prospect o£ entering Rome in a victorious army for many months. When the occasion finally arrived it was four thirty a.m. and light was just breaking over the Forum. We had not slept for three days and nights and had not much rest for five. We drove past the Colosseum, the monument of Victor Emmanuel II and St. Peter's and rumbled right on to pursue our fleeing enemy in the hills to the north. There was history and a lot of other things in the air that morning but the tired infantry had only to think of the snipers they knew they would meet across the Tiber.

All this fighting has been a very sobering experience. A lot of things slip away from us and in a sense this fierce baptism of fire has been a cleansing experience. It is not that a man's ideals change under fire. It's just that when he is in dirt and never knows if the next one will land in the hole with him—it's just that at times like this a lot of things—vanity, hypocrisy, pettiness, etc., assume their proper perspective and he is suddenly aware of his great desire for the simple honest, fundamental things of life. It clears your mind of rubbish. Everything seems stark naked on the battlefield and I think the experience can be looked upon as giving a man a place from which he can start. Perhaps it is the beginning of the affirmative stage of life. It is strange that our generation, brought up in highly complicated society —fast moving, streamlined, super-deluxe, and full of isms—must go to war to learn the simple truths that Ecclesiastes gave us so many centuries ago. I mention Ecclesiastes. It could have been others but he seems to be a very real friend. Ernie Pyle has told the story of the infantry in Italy and we soldiers in that branch are glad that he has done such an honest and competent job. It is a very necessary job too, I believe. I think he takes a little of the Hollywood out of the war for the people at home. This is good.

The average doughboy is not very bright. His education is poor. (Censoring his mail gives a painful revelation of how really inadequate it is.) But by God he is -winning this damn war for us. I want to tell a story about one of them. It isn't much of a story—rather a commonplace of daily fighting. But it will serve as an example. We had just taken a town and were in the street when the German counter-attack came. They shelled it of course and a kid in front of me suddenly turned around. The blood was gushing out of his neck and covering the front of his jacket. He looked scared. His own blood and so much of it! Before anyone could do anything for him he quietly walked over to the aid station for treatment. He was merely doing what was expected of him by being there in the first place (that takes more guts than some think), by taking care of himself when everyone else was busy as hell, and- by being a damn fine soldier. There is, as I said, nothing unusual in this story any more than in the burned crisp body of a tank commander who had also done what was expected of him. We don't think of him herothough some would I guess. You get used to such things, hate to see them happen, but know that they are inevitable. What I wonder most is: does it make any sense? It does make sense to us only insofar as the people at home have any conception of the fearful responsibility they have to those men who will not come back—those men who are dead now so that the rest of us can continue to lead individual, honest, decent lives. Are they aware of what men are doing so that America can continue to be an ever expanding idea? I know that our families are very much aware of this. I know that Dartmouth College is very much aware of it too. But read the news of the home front and what do you have? Cheap, stinking politics, narrow-minded stupidity, prejudice, greed, graft, racial hatred, strikes, and altogether an impression that the so-called leaders of our people have no more idea what this war is about than the pitiful Italian payeani who only know that their homes are being blown to pieces because of it. I am not interested in heroics or ridiculous meaningless slogans like "making the world safe for democracy" or even Atlantic Charters that seem to be forgotten as soon as they have served their useful political end. But Americans are carving out a tremendous opportunity for America and the world. The heartbreaking thing is that it does not seem that the country has produced the leaders or the leadership capable of handling it. Instead of "positive, affirmative, aggressive, intelligent leadership we get fence-straddling, haggling, petty bickering and name calling. I do not neces- sarily imply that Willkie was the only man for president, but he makes a good example of the fate of leadership that has ideas and is honest enough to declare them. Perhaps the soldiers who have fought will bring home a healthy bitterness with them. I don't mean a bitterness that demands gravy, bonuses, etc. (the Pentagon commandos will cry for that) hut I mean a bitterness that will demand honesty, sincerity, and intelligent leadership in all offices of government. This is the ideal, of course, but we may see a partial accomplishment of it. You see if we muff the ball this time, we have really lost the game!

I have talked much and my thoughts may seem rambling. I don't write this with the thought that you will publish it (though you can if you want to), but rather because I always wanted to know you and perhaps this is a good way to begin.

The following is an excerpt from a letter written by Robert A. Grey '46, son ofPete Grey '19, now in Burma with theAmerican Field Service. I believe it is thefirst letter from Burma published in thiscolumn.

We are with Gurkha troops and in case you are vague about Gurkhas, I'll tell you something of them. "Johnnie" Gurkha is a little man—tall at five feet-with a mongoloid head, round, and shaved; smiling always; and has stubby legs. He is the color, I suppose, of' a Chinese with a tan. He comes from the small independent state of Nepal in the Himalayas, between northeastern India and Tibet, and is one of the best fighters in the world. Against the Jap he has no equalhe's the best of them all.

The Gurkhas are funny little fellows, their voices childlike, and they talk with childish glee in a droll and ironic way. They grin like children; they are usually quiet and unobtrusive. Their idea of a big joke is to see someone else in a predicament that would be personally most unpleasant, perhaps fatal. To see another person in dire straits is the funniest thing in the world to them. The other day, for instance, Neil slipped on an escarpment and slid almost straight downward into mud for twenty feet. If he had not been stopped by some barbed wire, he would have slid another couple hundred feet. The wire, it so happened, was full of booby traps. Oh, how the Gurkhas loved that! They jumped up and down and laughed and laughed and finally threw Neil a rope and pulled him up. Had he landed on a booby trap they would have laughed twice as soon and twice as long.

They are fine troops and grand fighters. They do much of their fighting in these parts with eighteen-inch knives called Kukris.

A Gurkha Hvaldar whom I am friendly with is going to give me one of these knives, I think. He is an awfully nice chap —extremely intelligent and charming. He was educated at the University of Darjeeling and speaks excellent English.

This is our own little corner of the War here, and it's fascinating. I have become acquainted with most of the Gurkha officers (Englishmen) in this area. They are all excellent men. The bravest, most intelligent, capable, and charming men I have ever met. They fight under the most uncomfortable conditions imaginable; against the most savage and devilish enemy; and they are under the most perpetual, nervous strain, day and night, fighting or waiting. We see them every day in their front line positions, and talk with them for a few minutes, if there are no casualties for us to pick up. They tell us whether the night has been quiet or noisy; how many Japs they have killed, if any; the disposition of the Japs (who are often not more than forty or fifty yards from our forward trenches); and what improvements we have made in defenses, and so forth. You can see how interesting and personal this war is to us.

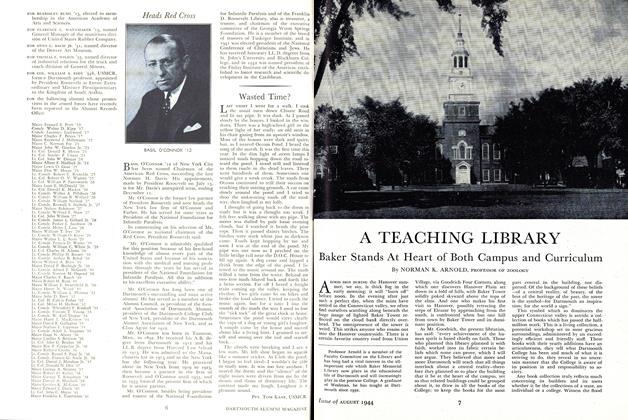

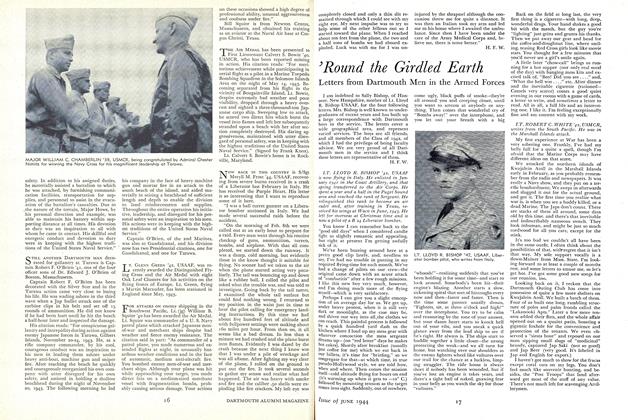

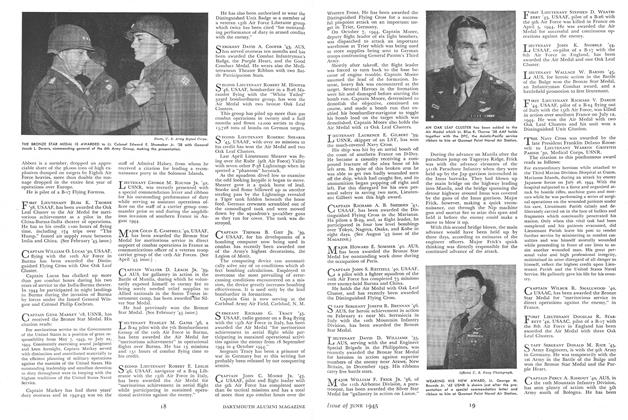

LT. HARRY BOND '42, whose letter from Italy is printed here, receives the Silver Star from General Mark Clark after Cassino.

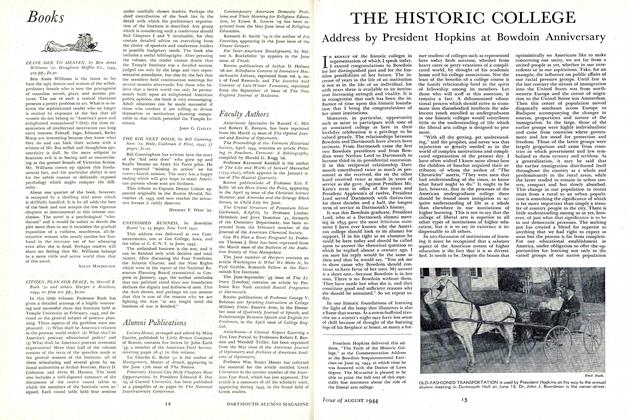

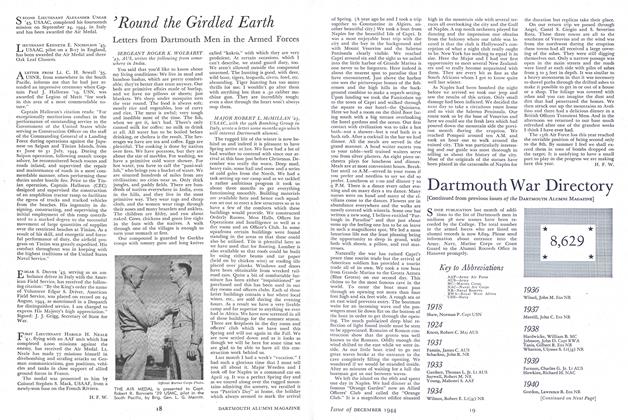

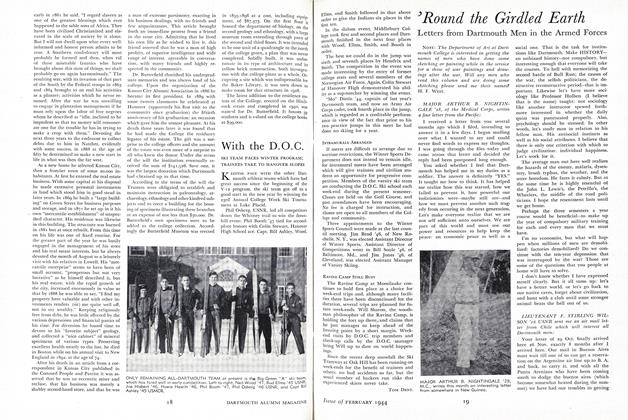

SIX DARTMOUTH MEN IN A JEEP in Egypt. They are Haiden Ritchie '44 (front), Robert C. Joy '45 (driver); in back, left to right, Frank M. Hutchins '45, Karl G. Sorg '44, Arthur M. Cox '42, William D. McNeely '45. Missing from photo: T. G. Larvtzas '45.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleA TEACHING LIBRARY

August 1944 By NORMAN K. ARNOLD -

Article

ArticleTHE HISTORIC COLLEGE

August 1944 -

Article

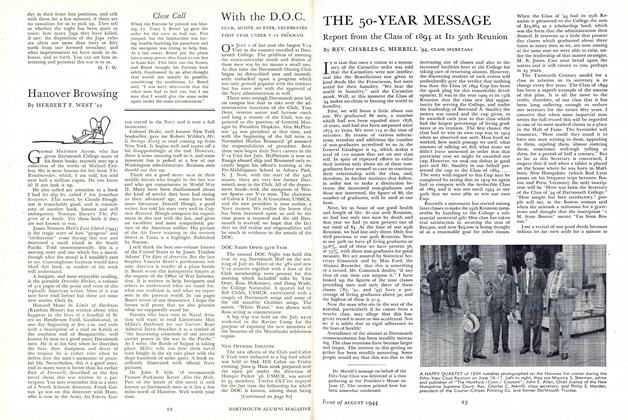

ArticleALUMNI OFFICERS MEET

August 1944 -

Article

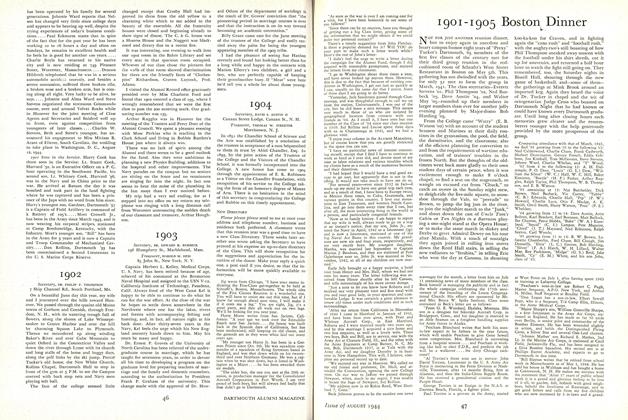

ArticleTHE 50-YEAR MESSAGE

August 1944 By REV. CHARLES C. MERRILL '94 -

Class Notes

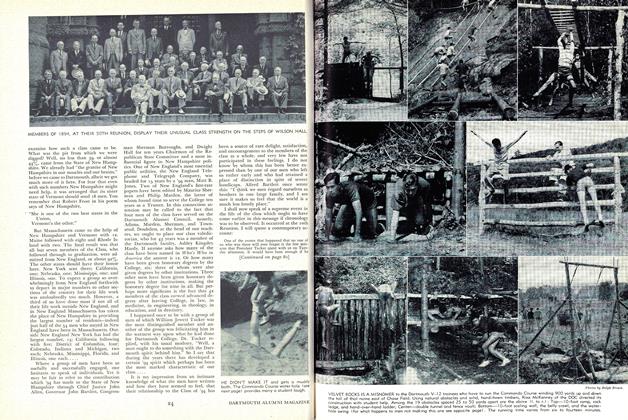

Class Notes1904

August 1944 By DAVID S. AUSTIN II, THOMAS W. STREETER -

Article

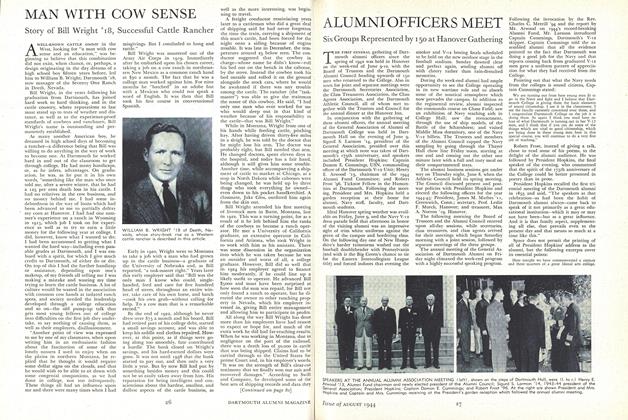

ArticleMAN WITH COW SENSE

August 1944 By A. P.

H. F. W.

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the Editor'Round the Girdled Earth

May 1943 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorRound the Girdled Earth

June 1944 -

Article

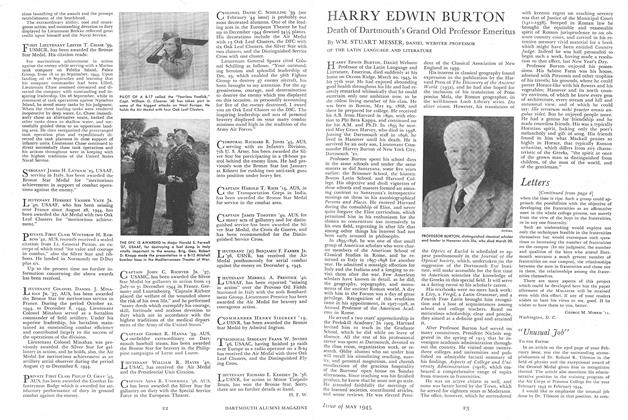

ArticleLaureled Sons of Dartmouth

December 1944 By H. F. W. -

Article

ArticleLaureled Sons of Dartmouth

February 1945 By H. F. W. -

Article

ArticleLaureled Sons of Dartmouth

May 1945 By H. F. W. -

Article

ArticleLaureled Sons of Dartmouth

June 1945 By H. F. W.

Lettter from the Editor

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorCOMMENCEMENT 1924

August 1924 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

NOVEMBER 1929 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

MAY 1930 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

MARCH 1931 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorWith Other Editors

APRIL 1932 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorLetters from Dartmouth Men in the Armed Forces

February 1944