Santo Domingo Finds Presented to College Museum

THIS IN AN ENDEAVOR to tell you of how I came to make a contribution to the Dartmouth College Museum. The brief glimpse of me as archaeologist is justified only by the generosity of your editor, and the hope that other alumni may be encouraged to contribute similarly.

My foray was into the Caribbean Sea. It was like going home again when the Air Forces sent me there as Air Attache early in 1943. This time the Sea looked smaller, but lovelier, for now I had a slick amphibian. Two years slid by, with close attention being devoted to enemy activities, and other complex problems. I was still blissfully ignorant of the charms of archaeology, until one day a friend, a professor of anthropology at a famous Latin American university, suggested that I go along with him to inspect some curious objects that had been reported to him from a nearby lonely key. The investigation uncovered some rather important information, in part of a military nature, and also unlocked for me the door to many remote areas of the West Indies, and the human mind.

As I worked my way further into the circle of amateur and professional archaeologists, with the perimeter ever expanding, I noted that the museums both private and public were bulging with marvelous specimens. I further noted that collectors hoarded their finds as though they were all of purest Jade—mind you, I refer to cracked bowls, bone spoons, and fish hooks, crude stone sinkers, flint daggers, and other such trivia. But I noted above all, in literature which I was boring into, that the Pre-Columbian inhabitants of the West Indies were very numerous indeed—the companions of Columbus, for example, have indicated that as many as 800,000 Taino Indians occupied Hispaniola (Santa Domingo plus Haiti). Surely, I concluded, the total collections of all the museums can represent only a very small proportion of the weapons and utensils and gadgets which the pre-historic Indians had fashioned and left behind them in the sands.

In 1944 I came up to Hanover on a short furlough and browsed about the. College Museum in company with Professor W. W. Bowen, the very personable and inspiring Curator. We concluded that it was up to me to help build up the West Indies archaeological section, and that the most promising way to go about it was to go digging myself, and not try to wangle specimens from other collectors (even your best archaeological friend frisks you as you leave his home, and vice versa).

Soon thereafter, on one of my periodic flights to Santo Domingo, and having attended to my military-diplomatic duties, I climbed into a car and followed the southern shore in an easterly direction from Ciudad Trujillo. I had previously noted that the shoreline was forbidding for an unbroken stretch of at least twenty miles. Sheer rock, twenty feet high, ran due east. Very few Dominicans live today along that stretch. I was reasonably sure that no prehistoric Indians had settled there either, lacking as it did egress to the sea. All this seemed to offer an excellent clue, and furthermore the soil was rich and level, many riverlets ran down the fertile fields to the sea, and, as I had learned, Ciudad Trujillo, with its fine little harbor carved out of the rocky shore by the Azamo River, had been the site of a very large Indian village in pre-Columbian times. The clue gave way to the supposition that an Indian village probably had existed precisely at the spot east of Ciudad Trujillo where the rocky shoreline would break, show a sandy cove, and march on.

I motored along hopefully. Once I stopped to ask a peasant if the road continued to hug the shore, but before I got to that question I had an inspiration and asked him instead if anyone along the road had a small boat that I could hire. The peasant said that several kilometers, further on I could have my choice of a dozen. I thanked him and disappeared up the road in a cloud of dust, elated with the prospects of finding the little cove, the first in the twenty-mile stretch from Ciudad Trujillo, where pre-historic man, like the present-day fishermen, could find an egress to the sea. My reasoning was, of course, pure supposition, for no Indian village had been known to exist in the vicinity. But very good luck was with me. Coming around a bend in the road I droye into a village of 70 to 80 thatched huts, fringing both sides of the road; and there was a little cove, with its inviting sandy beach where a dozen fishing craft nestled.

The cove was only about fifty feet wide at the mouth, with jagged rock bared like angry fangs on either side. Surely, I mused, this must be the site of a former Indian village; and approaching a group of dusky natives, I plied them with questions. The mayor of the village stepped forward, barefooted, and offered the disheartening opinion that no Indian village had existed in the vicinity, and that unfortunately there was no recollection of any Indian relics having been found in the village. An old toothless woman spoke up and recalled that time some years ago when some Americanos had dug up a few pieces of pottery down by the cove. Ah yes, the major agreed, he could remember the occasion, but added that that had been quite a while ago, and that no further interest had been shown in the matter (subsequently I have learned that the famous archaeologist, Dr. Herbert Kreiger of the Smithsonian Institute, was the inquisitive digger in question, and he had tarried briefly in this little village while en route to Andres, Boca Chica, and other wellknown Indian sites while gathering data for his renowned paper on pre-Columbian pottery). With hope undimmed I asked permission of the mayor to look about the village, and to do a bit of digging, which requests were readily granted. You can imagine my surprise and delight a few moments later, while strolling across a vacant lot, in finding there before my very eyes on the surface, a half dozen fragments of a buren (an open oven used by Indians to bake casabe bread). A little later I came upon a group of children playing with some figurines, which I recognized at once as handles from Indian pottery bowls, at least a half-century old. Here indeed, I concluded, is the site of an ancient and forgotten Indian village or cemetery. A quick glance around the village revealed other evidences of the Taino Indian civilization. This is it, I said, and began digging my trenches. In two hours I had unearthed five intact bowls, a handful of carved stone amulets, several water bottles, a bone spoon, and fifty-odd clay figurines. It was fantastic the way my hunch was working out. I dug on until dusk, by which time my treasure had grown to well over 500 specimens. I had at last begun to gather together my Dartmouth collection.

With each subsequent flight, back to Santo Domingo from my residence in Havana, I would resume my digging at La Caleta, the village with the cove, thus gradually adding to my collection, which by June of 1945 had grown to 1500 specimens. Another short furlough in July 1945 enabled me to bring back to Dartmouth about a third of the collection, which is now lodged in the College Museum. The balance will follow shortly. May it all contribute something new and valuable to our knowledge of early man in this hemisphere.

In an anthropological footnote we might mention that the Taino Indians who occupied the Greater Antilles had come originally from their ancestral home around the mouth of the Orinoco River, starting their migrations northward about a thousand years before the discovery of the New World by Columbus. They had been preceded by the Ciboney Indians, cave-dwellers, and pretty lowbrow all around. The Taino settled in Puerto Rico, Santo Domingo, Haiti, and eastern Cuba, where they led a peaceful, industrious agricultural life, based on the cultivation of the yucca plant. They were in the Polished Stone Age and had developed a more advanced culture than that of the same Age in the Old World. But the special point of this footnote is to tantalize you with some questions—Where did the Taino and the other South American tribes, including the Inca, Maya, and Aztec, come from originally? Where in fact did the tribes of North America come from? Did they come over from Siberia and China? And, if so, was it during or after the Glacial Period? And why is it that there is so little affinity or parallelism between the cultures of pre-historic inhabitants of North and South America? Could it be that the South American tribes came in boats across the Pacific Ocean? And how can we account for the presence of camel skeletons in North America but not in South America? .... Well, if you are now as thoroughly confused as I am, let's all decide to give a little heave to archaeology, and help the experts like Bowen and Denison of the Dartmouth College Museum to solve the riddles.

This concluding paragraph pays tribute to a Jugoslav artist, Ivan Gundrum, a resident of Havana, who was much taken by the decorative designs on the Taino specimens, so much so that he borrowed the basic motifs and, developing them into a series of several hundred wood carvings, created a neo-Taino art for application to modern fabrics, art objects, household articles, murals, or what you will. A few examples of neo-Taino Art are shown in the College Museum.

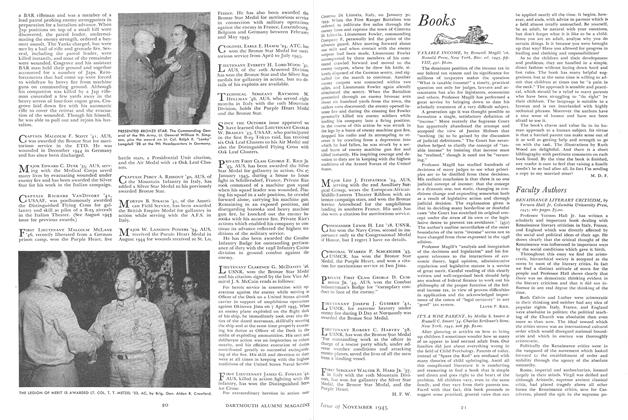

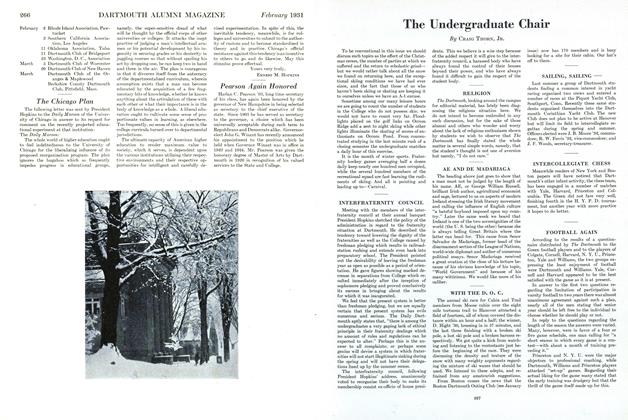

A DEMONSTRATION BY THE AUTHOR, Lt. Col. C. L. Youmans '20 (right), shows Prof. W. W. Bowetr, curator of the Dartmouth College Museum, how a Taino Indian burial bowl was used. Other pots in the collection are shown on the table, and in the background may be seen modern carvings by Ivan Gundrum, using the Taino decorative designs.

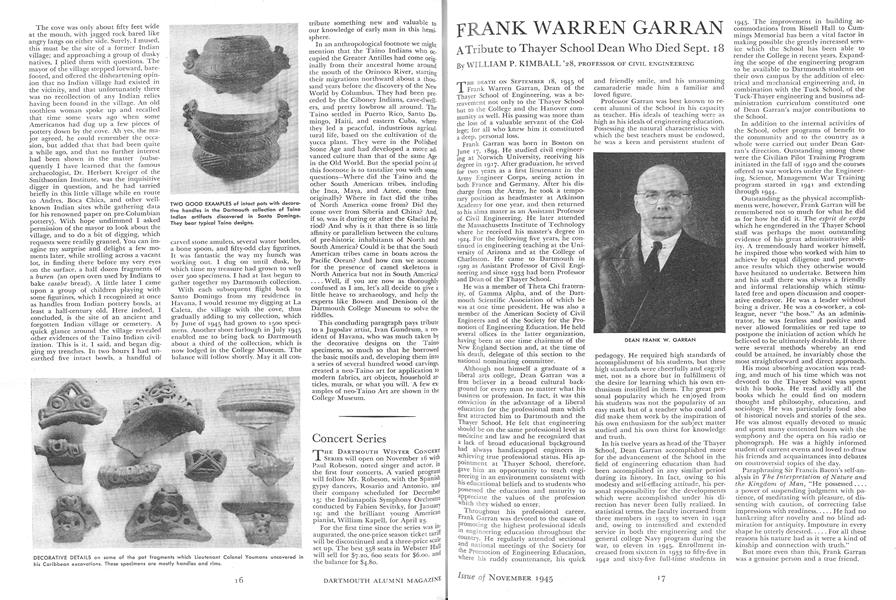

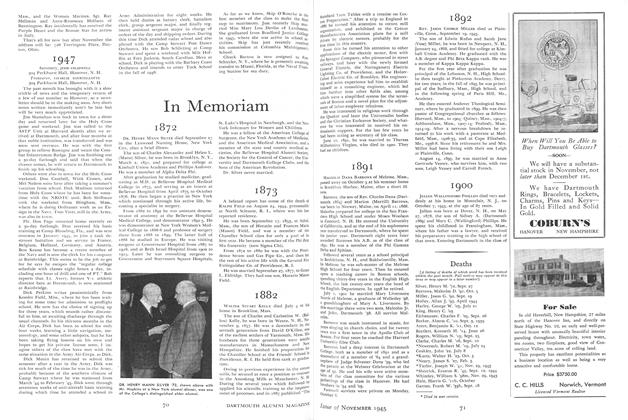

TWO GOOD EXAMPLES of intact pots with decorative handles in the Dartmouth collection of Taino Indian artifacts discovered in Santo Domingo. They bear typical Taino designs.

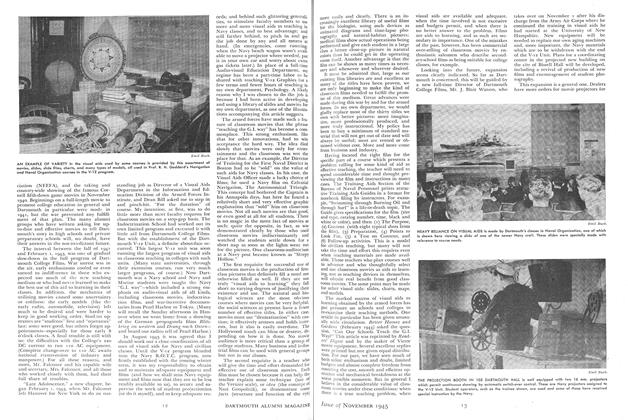

DECORATIVE DETAILS on some of the pot fragments which Lieutenant Colonel Youmans uncovered in his Caribbean excavations. These specimens are mostly handles and rims.

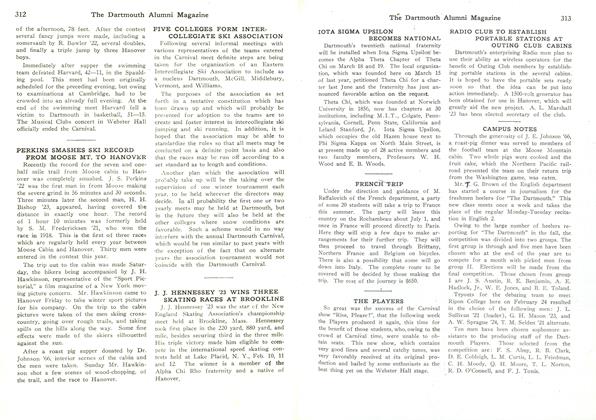

To his many hobbies which range from flying to photomontage, polo to poetry, Lt. Colonel Charles LeRoy Youmans '20 has added digging for archaeological specimens, an unusual interest for a former advertising executive and officer in the Air Corps. His first excavations were done for Dartmouth and the complete collection of his finds, Which have been presented to the Museum, will soon be on view there. Colonel Youmans is now at his farm in Orford, N. H.,; enjoying his terminal leave from the Air Corps, in which he served during the war as U. S. Air Attache to Haiti, Cuba, and the Dominican Republic. His son, Charles L. Youmans Jr. '45, left Dartmouth to join the Air Forces in the ETO as first pilot of a B-26 bomber. With Prof. Rene Herrara-Fritot, Colonel Youmans is the author of a book in Spanish about the La Caleta excavations. This is now coming off the Havana press, and an English version will be published in New York next spring.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleVISUAL AIDS TO LEARNING

November 1945 By C. N. ALLEN '24, -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

November 1945 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, T. TRUXTUN BRITTAN JR. -

Article

ArticleLaureled Sons of Dartmouth

November 1945 By H. F. W. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

November 1945 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1945

November 1945 By ARTHUR NICHOLS -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

November 1945

Article

-

Article

ArticleFRENCH TRIP

March 1921 -

Article

ArticleNotes from the Seventies

February 1935 -

Article

ArticleFive Seniors Receive Fulbright Scholarships

JUNE 1964 -

Article

ArticleTourek Helps Cambridge Defeat Oxford Rowers

MAY 1973 -

Article

ArticleFour Dartmouth docs got Together on One Recent Case

SEPTEMBER 1988 -

Article

ArticleAE AND DE MADARIAGA

February, 1931 By Craig Thorn Jr.