Dartmouth's Answer

To THE EDITOR:

During the recent months the Federal Government passed a G. I. Bill authorizing financial aid to honorably discharged servicemen for college education and vocational training. President Hutchins, University of Chicago, stated in a recent Collier's article that "colleges to obtain much needed financial income will do little (1) to keep out unqualified veterans, and (a) not expel those who fail."

I am certain that the Alumni will be interested in both Dartmouth's answer to these charges as well as its expected aid to future members of the student body. Such an article could dispel any possible alarm that Dartmouth, in the future, will lower its entrance requirements or pigeon-hole its peace-time "selective system."

Several weeks ago I returned from two years' duty overseas, and have been out of touch with Dartmouth more or less during that time. Perhaps this subject has already been covered elsewhere previously.

South Pasadena, Calif.

EDITOR'S NOTE: There is no intention or expectation on the part of any College official that veterans financing their education by means of the G. I. Bill of Rights will be granted a lower standard of admission to Dartmouth or that, once admitted, they will be excused from any of the qualitative academic standards of the College. The Special Committee on Academic Adjustments, created by the Board of Trustees to. handle the cases of returning servicemen, has already stated its belief that Dartmouth's admissions problem in the immediate postwar period will be one of selection from an over-abundance of applicants, and in anticipation of that situation it has announced a tentative list of admissions priorities (see November 1944 issue). Any college taking the interests of veteran-students to heart, and Dartmouth is one such, ought to be guided by the fact that the serviceman who flunks out of college forfeits his right to further government-financed education. It would certainly be a disservice to the veteran to admit him to college without evidence that he can handle the academic work, and this is just one additional reason why Dartmouth will not lower its admissions or academic standards for the returning serviceman.

Identification

To THE EDITOR:

On page 51 of the February issue of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE appears a picture of a "Pick-up Hockey Team." The unidentified man beside Bill Paisley '23 looks very much like Horace G. Hawks. I believe his class was 1919 and that his home was in Newton Center, Mass., also that he had an older brother on the Dartmouth varsity hockey team a few years before him.

I assume that you are interested in identification "for the record" and send this along for what it is worth. You may receive corroboration from other sources. "Hawker, as we knew him, was my most intimate friend after graduation, and a finer chap or truer friend there never was. He died in 1940 with a heart ailment of long standing.

New York, N. Y.

"Personal Opinions"

To THE EDITOR:

I noticed an open letter to President Hopkins by Carl Hess '34 in the October issue. Frankly, this epistle so amazed me that I had to re-read it three or four times to believe it.

Hess is undoubtedly a very fine, intelligent chap, and he certainly writes well, but never have I seen such extreme idealism coupled with what I deem a rather unreal concept of the world. First, his turning to the College at all shows a search for an absolute much in the manner in which other intellectuals turn to the Catholic Church or (in other years) the Communist Party. I have always considered Dartmouth as a place, a jumping off place if you will, where one was prepared to meet the world but which could provide no final answers. It is true that the secure, ordered atmosphere of the College (much like the world of the 12th Century Renaissance) with Green Key, C & G, Palaeop, etc., as preordained standards, and with no economic problem whatsoever, is something that perhaps too many alumni look back on with longing. None the less it is not the world, and the simple problems of student government there have little or no correlation with the outside.

Secondly, I find a flaw in his concern with improving the world (in a rather abstract fashion), however sincere. Like Horace, Lucretius, Voltaire, Housman, Maugham and so many others, I tend to take the world pretty much as I find it. This has come less from reading than from experience. I have come to the conclusion that human relationships are incredibly complex and that to divide people, or classes of people, into "good" and ' bad categories is to be guilty of gross oversimplification.

If a man wants to "do good" in the world let him bring up his child right, or run his business decently, or be good to his wife (if she merits it), vote according to his lights, and stop worrying about a large scope of activity.

If a man wants to reform the world through politics let him read the penetrating works of Thurman Arnold or Burnham (I liked his The Machiavellian) before he takes any definite steps.

I enjoyed the mature wisdom of President Hopkins' reply. I do disagree mildy with one or two statements he makes. True, espousing causes often narrows a man and brings more havoc than harmony. But, at the same time to back a cause is to get something done, to gain an objective. In the world it is often impossible to maintain a detached liberalism and accomplish things—whether for good or evil being up to the individual.

I also question whether, by the very nature of all organization, business or labor will rid themselves of "lunatic fringes" any more than the Catholic Church which produced Archbishop Spellman will rid itself of Father Coughlin. Such phenomena are an integral part of any social group.

Secondly, "business" and "labor" are abstractions, and in a sense meaningless descriptive words. There is no correlation between the labor policy of Henry Kaiser and Sewall Avery, any more than there is any connection between the way James Petrillo runs his union and Sidney Hillman runs his. That is Democracy, I guess. At any rate superficial judgments on "business" and "labor" by radicals and Bourbons make little sense to me. The "rational" man tries to pigeonhole things and damned if I have discovered much in life which can be neatly fitted in a slot.

However, these are purely personal opinions, humbly offered, and are not in any sense meant to detract from the kindly, urbane wisdom of President Hopkins, whom I have always admired so very much. His reply was priceless.

A.P.0., New York City.

cc Opposite Advice"

The following excerpts are from a copy of an open letter to Carl B. Hess '34 written by Prof. Paul A. Schilpp of the Department of Philosophy, Northwestern University, following publication in last October's issue of the MAGAZINE of an exchange of letters between Mr. Hess and President Hopkins concerning the role of "an educated young man of good will" in the world today. Space is not available to print all of the long and detailed letter sent to us by Professor Schilpp.

MY DEAR MR. HESS:

In the fifth paragraph of your letter you voice your sincere "humiliation" at having gone through college "with such naivete," and—with your friends—of having "failed in your responsibility" of "moulding student opinion." As a college-instructor now in my 23rd year of college-teaching, perhaps you will permit me to say that you and your friends were not the exception, but rather the rule. Even now, in the midst of the present chaotic world situation, most college students still go through and graduate from college with what, on the whole, is an unbelievable naivete. Most of them still do not know what the score is when they finally get that coveted diploma. But it is one thing to attest to the fact; it is another to find the causes of and/or reasons for this sad fact. Your letter seems to assume that the major blame for such unbelievable naivete on the part of young college-graduates is to be assumed by the graduates themselves. This is, of course, true in part; but only in part. (Cf. on this students' blame an anonymous article which appeared in the now defunct Outlook, for March 2nd, 1927, pages 270-271, under the title "Let's Not Think." Essentially I am of the opinion that the anonymous undergraduate's complaint is still largelyvalid.) But, has it not occurred to you that, if this failure of college even of so called "good colleges"—to educate men for the purpose of living, for the purpose of providing leadership, and for the purpose of helping men to understand the world and their own "covenants with it," if this failure is nation-wide and true of one student-generation after another, the reasons for such failure can not be sought solely in the students themselves? Your own loyalty to your Alma Mater, and the way she looms up in your memory the farther you get away from her, seem to have blinded you to facts which, between the lines, crop out even in your own letter. Remember your questions addressed to Professor Eddy "before Munich, but after the Spanish Civil War?" And what about the answer you got from Professor Eddy? And now President Hopkins' reply to your letter is certainly on a not much higher plane than was Professor Eddy's answer some years ago. Is all this merely an accident? Or is it more likely that these are evidences of the fact that things are basically wrong in our highest institutions of learning? Perhaps education, as conceived by most educators under the impact of a capitalist-controlled educational system, is not intended to produce a leadership which would lead into a new (and different) kind of a world. Perhaps education is basically thought of as "fitting men into their environment," even if that environment stinks to high heaven, as certainly today's world does! Perhaps the purpose of education is to make men and keep them satisfied with the status quo (defined by the Negro preacher as "de hell of a mess we're in"). And, if so, it is easy to see what's wrong with you and with your letter and its searching questions: although you were true to form 10 years ago—and therefore were an honor to your Alma Mater—you seem (quite unaccountably) to have awakened from the stupor into which your college-education was supposed to have immersed you for the rest of your natural life. No wonder, President Hopkins' reply aims at getting you back into your—expected—stupor and sleep again!

In the ninth paragraph of your letter you raise the all-important question: "To whatends shall I devote myself?" Permit me to begin by answering you in your own terms. Do you know any greater ends than "Truth, Peace, Progress, Virtue, Wisdom or just Contentment on this earth?" So far, so good; for there are no nobler ends than these.

But you are, of course, quite right in calling attention to the fact that giving lip-service to these great and all-inclusive ends not only is "not sufficient," but rather is hopelessly futile when one remembers that most everyone is perfectly willing to accept those ideals as ideal ends, but hardly anyone is doing anything about realizing them in fact. Even Hitler has said that he "wants peace." And how many Americans, who are digging deeper and deeper into their pockets in support of the war, ever dug one-twentieth as deep into their pockets to advance the causes of peace and to do constructive and creative tasks of bringing about and maintaining world brotherhood?

You ask: "Should I espouse a cause?" Permit me, at this point, to give you the diametrically opposite advice from that given you by President Hopkins. By all means, espouse a cause! Socrates had a cause. So did Jesus of Nazareth. St. Paul had a cause. And so did Thomas Aquinas. Lincoln had a cause. And so did Florence Nightingale. In fact, I can't think of the name of any human being who made any perceptible difference in human society who did not have a cause. When President Hopkins, in answering this question of yours negatively insists that "a college man who devotes himself exclusively (sic!) to the demands of a cause, regardlessof its changing relationship to society fromtime to time, stultifies himself and largely impairs his usefulness...he is clearly throwing sand in your eyes by begging the whole question by inserting the word and clause which I have underscored. Neither the word "exclusively" nor the longer clause "regardless .... time" appeared anywhere in your letter or in your question. Hasn't President Hopkins himself devoted a pretty fair portion of his life to the cause of Dartmouth College? Or is Dartmouth no "cause" just because President Hopkins has not devoted himself to Dartmouth "exclusively" and just because his devotion to the College has not been "regardless of its changing relationship to society from time to time?" That's a terribly narrow and wholly unjustified interpretation of a "cause," and I want to repeat that there is absolutely nothing in your own letter either to warrant such an interpretation or even to offer an opening for it. One can only surmise, therefore, what may have been thebe they conscious or subconscious reasons which prompted President Hopkins to engage in such a one-sided, biased, and wholly unwarranted tirade on a college-man's devotion to a "cause." Is he afraid that you might turn social reformer, prohibitionist, crusader for human rights, or even horror of horrors communist? Obviously I can not know the answer to this question. But I do know that Lincoln's life and work are wholly inexplicable aside from his sacred resolve, made when, as a mere youth, he saw his first slavemarket: human beings auctioned off to the highest bidder like so many cattle, he is reported to have muttered to himself: "If ever I get a chance to hit this thing, I'll hit it hard!" Lincoln had found his Cause! Is it too far fetched to suggest that, perhaps, the major reasons for the miserable failure on the part of college men to be able to lead humanity into a better world may be found precisely in the fact that the overwhelming majority of college graduates America's colleges and universities have turned out thus far never have yet been able to find a bigger or more significant "cause" than their own personal (economic) welfare and that of the immediate members of their family? To me, at any rate, it comes as a horrible shock that any college teacher—let alone a college president should be willing to advise any college man to be satisfied with such an unbelievably low aim in life. Humanity finds itself in the "hell of a mess" of today's unbelievably savage abyss precisely because not merely 99% of all college graduates, but 99%.. of all the rest of the population also are satisfied so long as they are able to keep themselves "and such family as they may have accumulated" in reasonable degrees of economic decency

A cause? Yes, by all means a CAUSE! How can any man—regardless of whether he is a college graduate or never even finished grammar school—have less than a cause in such a world as this? In a world of the newer barbarisms and machine-age savagery, of two world-wars in one generation, surely in such a world no self-respecting person can live without devotion to a cause—i.e., without doing all in his power to DO SOMETHING constructive to remedy such unbearable situations, something to see to it that these world catastrophies are not endlessly repeated.

I need hardly tell you that to accomplish such an end requires not one but many things along many different lines. Since the causes of war are multitudinous, so must be its cures. At which particular one (or more than one) of these you level your attack is entirely up to you, and will undoubtedly be largely determined by your own particular interests on the one hand and by your specific kind of equipment and training on the other. In other words, at which particular point of leverage you set in is a matter which is a peculiarly personal, individual and unique problem. But that you must in some specific fashion attack the problems of helping to create a new kind of a world or, as you put it yourself, "contribute to the establishment of Truth, Peace, Progress, Virtue, Wisdom, or just Contentment on this earth" this your own letter makes indubitable.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleSCHOOL FOR CRAFTSMEN

March 1945 By C. E. W. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

March 1945 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, T. TRUXTON BRITTAN JR. -

Article

ArticleLaureled Sons of Dartmouth

March 1945 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

March 1945 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Article

Article'Round the Girdled Earth

March 1945 By H. F. W. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1919

March 1945 By J. KENNETH HUNTINGTON, MAX A. NORTON

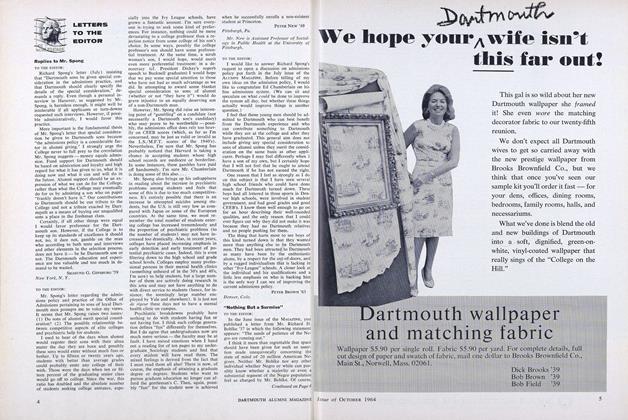

Letters to the Editor

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLETTERS TO THE EDITOR

OCTOBER 1964 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

APRIL 1967 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

SEPTEMBER 1984 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLETTERS

MAY 1989 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorThe Healing Power Of Smarts

January 1996 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

Sept/Oct 2009