I am the Secretary's secretary, and as he is mud-bound in the wilds of Arkansas while I have full custody and control over the class News file, I delight in the opportunity to have first-hand contact with the class. I have been through the unused material and think that the following letter from Teheran, Iran, December to, is so good that it should fill the bill for this month:

This letter is addressed to all our many friends to whom we would like to write individually, but who we realize, as the business of the days consumes us and the months slip by, may not hear from us soon otherwise.

For the benefit of those who haven't heard, we Torberts, Will, Dorothy, Ellison and Preston, have gone to Iran (Persia) and have been living in Teheran since early September.

Only a few months ago, Iran to us was the vague land of Omar Khyaam. Things happened quickly and with little time for leave-taking Dorothy and the youngsters were on their way by one route, I by another.

My job is with the American Financial Mission to Iran as administrator of Teheran distribution; Dorothy's job is to grapple with the gross inefficiencies of Persian help, the difficulties of language differences, and to run the household in spite of them; Ellison, now four years old, spends his mornings at a school with two Russian, two Arab and four Armenian kids, none of. whom speak any English. Preston occupies himself trying to walk more than a couple of consecutive steps. All of us enjoy the best health. Three months of Iran have agreed with us.

We have a modern, comfortable house and garden with swimming pool, enclosed, like all such residences, by a high wall, which helps keep out the street dust as well as dubious characters. When a ten-penny nail is worth a nickel, a tire $l,OOO and your car $15,000, a wall, night lights in the garden, a good dog and a husky man servant on the premises are all conducive to sounder sleep.

Parts of Teheran are fairly modern in appearance and construction; many of the main streets are paved. But as a whole it is far from modern. There is no water system except the system of ditches ("jubes"), from which one diverts his water to a storage pool and pump for household use. It looks bad, smells bad, and is bad; no foreigner dares drink it raw, i.e., without boiling.

Such a water system, and the Persians' complete ignorance of sanitation creates queer sights. Along a few blocks in the same water a camel drinks, car is washed, a naked child is scrubbed, dishes are cleaned, clothes are washed, and a man in pajamas douses his face and brushes his teeth. Perchance an alien orange peel or worse interrupts his routine; he calmly watches it float by and continues his lavation.

Motoring in Teheran is a novelty not for the nervous. To begin with, the streets are mostly narrow; they are filled with laden donkeys, camels, burro-drawn carts with the wobbliest' wheels imaginable, drosnkies with wheels likewise, rolling in three directions at once, coolies toting heavy bales, men with little shovels and empty oil tins following closely on the heels of horses, and swarms of pedestrians who, like chickens, have no reason to cross but to get on the other side. Since most of these animals and people are unaccustomed to motor vehicles, their reactions are very slow, and occasionally from surprise at finding an auto at his heels, a native will fall flat across the road, and if not that, usually jumps back into the path of the car rather than out of it.

Into this animal and vehicle bedlam project the automobile with its Persian driver no driving license required, careless of human life, unable to judge speed, distance or angles of interception, tion, ruthless in maintaining his prestige by forcing other drivers aside and behind, and utter lack of consideration for others, or fear of fines or punishment. He steps on the gas, blows his horn constantly (both to attract attention and clear the way) careens in and out, on the left or right side, whichever is clearer, disregards the ineffective'policemen, and pulls up to either curb to let you out—if you can by that time get out! Here one suddenly realizes why the looped straps by the back seat. Every rider perforce is a straphanger in Teheran.

When a car gets smashed or breaks down and can't roll on its four wheels, the repairs are made in the street, even if the repair takes several days. It is cheaper to hire a guard than to haul it to a garage. Tow cars are unknown. Recently a truck broke an axle in the middle of the main street. There it remained for more than a week, with mechanics repairing in the midst of traffic.

Obtaining even the commonest services here is difficult and complicated. In this whole city of nearly a million population and several thousand cars busses, trucks and motorcycles there are only five gasoline stations. To get gas one often waits in line for half an hour. And then no services goes with the gas—no windshield cleaning no water for the radiator, no free air for tire's. The gas stations don't even have air at a price.

I recently went through the exasperating ordeal of getting air in my tires at one of the few garages which has compressed air. After worming the car through two narrow doorways, I explained through my interpreter that I wanted air in the tires. Much talk ensued. They wanted me to leave the car. No, I wanted the air now and where was the hose? There, at the back of a stall wherein an old jalopy reclined, on two flat tires. After several fruitless attempts to start it two other employees were called to push; all four directed each other's efforts and completely confused coordinated effort but finally managed to maneuver it out. I drove into the stall. The air hose was short and with plain end, no nib to fit over the valve stem. So one "mechanic" held the hose end tight against the valve stem while another operated the faucet-like valve near the air tank—always opening it at the wrong moment, either before his partner in confusion had the hose end placed or after he had removed it. Tons of air escaped, throwing up clouds of dust. Did I have a tire gauge? No, they could keep at it until the "bends" were out, I'd be content with that. After some practise and much bickering their efforts were sufficiently coordinated that some slight additional pressure went into the tires and finally both front tires were relieved of their bends. The mechanics smiled triumphantly; they were pleasing the American (they thought!). Now the hose was a little short; would I please take the car out and back in so they could reach the rear tires? I backed into the narrow alley, sawed, cut and filled myself into a lather while all four mechanics and several other native loafers shouted Farsi directions which 1 couldn't understand and would ill have followed had I understood. Finally when some additional bit of pressure had been squeezed into the rears, the manager, distinguishable only because his clothes were a little less ragged than the others, strutted out to examine the job, to ask it everything was satisfactory and, not his least interest, to demand 20 rials. That bit of air cost 40 minutes times and the equivalent of 60c!! During the time I was counting ten I recalled the wisdom of a local sage, "To succeed in Persia one must have infinite patience and a sense or humor." By the time I'd reached ten, I smiled my best and handed over the 20 rials.

Good food, a matter of considerable difficulty in the Middle East, is available to us through the courtesy of the officers' mess at Camp Amirabad, Headquarters of the U. S. Army Persian Gulf Command. We drive about five miles to the camp for most of our meals, which are good wholesome American cooking, a novelty in these parts. A very few and night clubs serve meals, excellent by Persian standards but only passable by ours.

Ellison, being the only American child taking meals at Amirabad, gets much attention from the officers and takes lieutenants to generals in his stride.

Everything is scarce here except people, dust and dirt. Scarcities create interesting situations. Native glassware, for instance, is very expensive and of poor quality. Hence an empty whiskey, gin or vodka bottle is worth about sixty cents. Water pitchers are unheard of; the best hotels, restaurants, and homes bring water to table in old liquor bottles. We have a colonel friend who for breakfast dashes down a huge glass of grapefruit juice, diluted half with water. He too uses old vodka bottles for his water. One morning his cook mistook a "live" vodka bottle for water, the colonel tossed down his juice, smacked his lips, knitted his brow, shuddered, flushed, and tottered off to bed for the rest of the day.

War, of course, has greatly exaggerated scarcities and has inflated prices. Price fluctuations are severe and markets for most finished goods are so limited—-few people can afford more than bare necessities—-that a relatively small quantity imported will cause drastic reactions. Six months ago an ordinary light bulb cost about $10; a few thousand were imported; the price is now about 75c. Importation of a few thousand neckties from Switzerland reduced the price recently from $7 to $1. War-end psychology has reduced most prices about 50% in the last three months. But nothing is reasonable yet. The 1942 Buicks are $15,000, electric refrigerators $1500, flatirons $35, men's suits $200, shirts $12, shoes $50, a small cup of poor coffee 30c, a chocolate eclair 50c and percale sheets $15.

Scarcity of essentials and the accompanying inflation are the main reasons for the Mission's being. We comprise about forty members, all Americans, employed by the Iranian government. Our job is principally managing the finances of the country and obtaining and distributing essential commodities. Our greatest difficulties are in finding honest Iranian government employees to assist "the execution of our programs. Most of them can be depended upon only to complicate and fritz up our work so some advantage will accrue to themselves. And the average business man knows no law but profit. I during the last, two years of catching violators in New York, that I'd learned most of the angles, but here I found myself a neophyte. New York is the elementary, this the graduate school of the Fine Arts of Finagling.

We miss contact with you. Should you drop us a note Airmail c/o Millspaugh Mission, A.P.O. 523, Postmaster New York City we'd have it in eight or ten days and be mighty delighted. Meanwhile we remain, Cordially yours, Will and Dorothy Torbert.

Secretary, 75 Federal St., Boston, Mass. Treasurer, Batten, Barton, Durstine & Osborn 383 Madison Ave., New York, N. Y.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleSCHOOL FOR CRAFTSMEN

March 1945 By C. E. W. -

Article

ArticleLaureled Sons of Dartmouth

March 1945 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

March 1945 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Article

Article'Round the Girdled Earth

March 1945 By H. F. W. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1919

March 1945 By J. KENNETH HUNTINGTON, MAX A. NORTON -

Sports

SportsWith Big Green Teams

March 1945 By Francis E. Merrill '26

F. WILLIAM ANDRES

-

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1929

May 1935 By F. William Andres -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

January 1948 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, EDWIN C. CHINLUND -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

November 1943 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, T. TRUXTON BRITTAN JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

February 1944 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, T. TRUXTON BRITTAN JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

June 1945 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, T. TRUXTUN BRITTAN JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

April 1946 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, T. TRUXTUN BRITTAN JR.

T. TRUXTON BRITTAN JR.

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

December 1943 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, T. TRUXTON BRITTAN JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

January 1944 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, T. TRUXTON BRITTAN JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

April 1944 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, T. TRUXTON BRITTAN JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

June 1944 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, T. TRUXTON BRITTAN JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

November 1944 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, T. TRUXTON BRITTAN JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

January 1945 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, T. TRUXTON BRITTAN JR.

Class Notes

-

Class Notes

Class NotesPACIFIC COAST ALUMNI PLAN POW WOW FOR THIS SUMMER

June 1929 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1930

APRIL 1971 By CHARLES V. RAYMOND, ARTHUR M. BROWNING -

Class Notes

Class Notes1948

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1983 By Francis R. Drury Jr. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1931

February 1958 By JOHN H. RENO, PETER B. EVANS, JAMES B. GODFREY -

Class Notes

Class Notes1968

NOVEMBER 1988 By Parker J. Beverage -

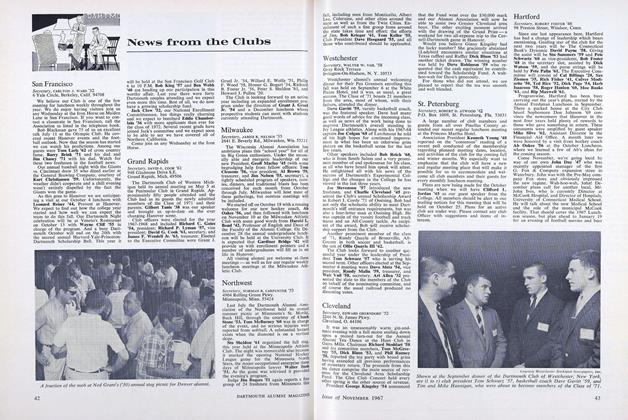

Class Notes

Class NotesSt. Petersburg

NOVEMBER 1967 By ROBERT D. ATWOOD '42