Letters from Dartmouth Men in the Armed Forces

FIRST LIEUTENANT CHARLES 13.

McLANE '41, AUS, writes this most nostalgic account of Paris which I'm sure willinterest you.

"Que Fais-Tu, Paris?"

This was the title of a song we heard at three o'clock the other morning in a third-rate cabaret off the Avenue de 1' Opera. We thought it was one of the most moving songs we had ever heard. The girl who sang it is unknown. She was a heavy, languid, rouged Parisian who had never been beyond the Porte d'Orleans and who made her living off the idleness and vice of thousands who came to the third-rate cabaret to forget and left remembering. Her voice was throaty and barbaric and sometimes so vibrant that the champagne glasses jiggled on the tables. The song was about Paris—during the occupation and since. It was sentimental and sarcastic and shrewd; it was scolding and ashamed and loving. The song and the way this rouged Parisian demimondaine sang it made us love Paris, and we thought we would take time out here to wonder why.

We love the broad sweeps and the space of the city—from the Madeleine across the Place de la Concorde to Les Invalides, from the Trocadero to the Eiffel Tower, from the fitoile to the Louvre. We love the breadth and dignity of the avenues—the Champs Elysees, Marechal Foch, the Grand Boulevard. We love the endless intricacy of the Bois de Boulogne, neater than Hyde but not so polished as Central Park. We love the feel of the people at dusk on their way home, in the Metro, on Sunday after- noons along the boulevards. We love their jabbering and curiosity; their quickness to resent an injury, their quickness to forget. Shake a Frenchman's hand and he's for- given everything—everything except the Germans being here. We love the looks of Parisian women—the pride and pains of their toilette and their clothes, their chic, and still their touchableness. We love the intensity of Frenchmen, the way they take life seriously and finding it worth while living, live it strenuously in every sense they know. And then there are a hundred special places and moods we love—from Sacre Coeur by moonlight to the market place near Chatelet at ten o'clock; from Saturday night at the Cirque Medrano to Sunday afternoon at the Luxembourg Gar- dens; from picking up paper-bound vol- umes in the book-stalls to lunching in a Chinese restaurant in the Sorbonne. We love the layout of the town—the width and depth and timelessness of Paris.

Our mother wrote the other day that in Paris she always fell in love all over again with our father. Which is about as neat a compliment as Paris could wish for. There is something in the air that makes you want to laugh and cry at the same time- like a Strauss waltz or the band playing at an October football game. You want to be in love with something, and sometimes it's hard to know your New England blood runs cool and sure and you know you can't let yourself go because all you can ever really love is several thousand miles away.

We like to see French people from the Dordogne and Auvergne and Haute Sa- voie in Paris. They are as much at home as if they were in their hometowns. Ben Little would be embarrassed and self-con- scious in New York; but no Breton or Nor- man or Charentais ever feels lost in Paris. Because Paris belongs to France, and the city belongs as much to them as to the ones who live here all their lives.

So that the richness and the beauty of Paris is the richness and beauty of France. And the weakness too—let's talk for a minute about the weakness. Because loving isn't always admiring. We may be slightly blinded by the warmth and graciousness of France, but we're far from thinking she has emerged from her humiliation strong and unified and deserving. We regret the lack of trust in one another. We regret the inability of Frenchmen to lay aside old prejudices and plan the future together. We regret the smugness and fears of the bourgeoisie; and just as much we regret the snooping and underhanded methods of the Communists, who banking on their new prestige as leaders in the resistance, are trying to force a hand. If France is going Communist, let her go, we say, but let her go in the open.

We regret too the ease with which Frenchmen finagle their way into our gas supply with tempting prices to a negro driver whose fifty dollars gets him only two good nights a month. We regret their irresponsibility—we don't know how many Red Ball hours have been lost because of French carts and trucks on roads that every half a kilometer are marked: "Interdit au traffique civile."

Also we regret the lack of leaders here. We regret that the best they have, deGaulle, although accepted superficially, is only tolerated underneath. Better at this stage, we think, to put all their faith in him, and work to make him greater. (We were sorry to read in the last Clatter that our sister thought it too bad that in Roosevelt and Dewey we had such poor leaders to choose from. Had she seen France she might have been satisfied, as we were, that the choice was so rich.)

So France is shaken, maybe for a year, maybe a decade, maybe a century. But we don't love Frenchmen less. And if you are weary of listening to complaints and trying to figure out the merits of 15 odd political parties trying to outdo each other, then you have only to walk down along the Seine, across the Cite, past Notre Dame and back along the left bank, as we did earlier this evening, and your love is reborn all over again—like the Strauss waltz or the October football game.

But we are of the mountains and the narrow back roads and we are anxious to get back to them. We have been grateful for this chance to live in Paris, but two months is a long time and we're looking forward to going south soon.

CORPORAL JAMES A. PETREQUIN

'35, AUS, a cousin of Bud Petrequin '25,writes a newsy letter from Belgium. Theletter was written in late 1944.

Your letter with this year's first Bulletin arrived a couple of hours ago and I am especially glad to have it for a number of reasons. Ever since the mad dash across France was finished a few weeks ago we've had more leisure and I've been wanting to write you, but as I had left all my personal effects including address book on the other side of the Channel for security reasons I've been unable to do it till now. Particularly when the August issue of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE came a couple of weeks ago, I became most nostalgic for Hanover since we were then in parts of Belgium and Luxembourg which are far and away the finest bits of country we've seen and most intensely reminiscent of the northern Connecticut valley. Today we have had the winter's first heavy fall of snow and I am fairly in a blue funk for Balch Hill or Occom Pond as I look at the snowladen firs and the rolling hills and valleys. I must confess that the rumble of artillery and an occasional roar of tanks is alien to the scene as is the eight or ten inches of mud now happily camouflaged for a few hours by the snow, but no less tenacious. And my pup tent, almost collapsing from the added weight is a far cry from Woodward Hall (where I once enjoyed the luxury of a private latrine!!)— Don't think I'm trying to emulate A.l.D.'s descriptions of the Elm; it's just that we get too much time to think and Dartmouth has been more than usually in my thoughts. I am grateful to learn—just in time—that tomorrow night is Dartmouth Night although I've had the bad luck to find no fellow-alumni since we left England and I shall have to drink a toast alone, but rest assured the College will be in my grateful prayers.

Most of your questions can be answered in a brief narrative of our adventures since early'last spring when last I wrote. We were at that time engaged in the secret job of helping the D-day boys get ready and take off on the fateful sixth. Watching those guys go into what we were sure would be a costly affair, will be always one of the most awesome and yet inspiring experiences of my life. The part of it in which we take the most pride was perhaps the successful maintenance of secrecy. A week before we left I paid a short visit to cousins in London and shared with them for a day and a night the state of siege from those diabolical flying bombs. Damage was accurately reported in the U. S. dispatches (for a change) so far as I could tell and though I have experienced the same sort of thing subsequently in the field, it is difficult to describe or compare the apprehensive anticipation they stimulate in a dense city where there are so many helpless people all around. Since then these same cousins have lost their roof and all their windows but were unhurt and suffered no further damage. The utter military uselessness of that weapon is, I believe, the most despicable thing about its employment. Be that as it may, we left England with brand new equipment late in July and landed roughly D + 50—in time to spearhead the now famous break-through and to be in the lead of the southern jaw of the pincers on the Falaise gap. I believe we established some sort of record for speed, distance, enemy destroyed, and thank God, lowness of our own casualties. We rested only a matter of days after that first month and then passed through Paris a day after its liberation—the first U. S. armor to get there in fact,—made a long thrust north to the Belgian border and then were recalled because we had too far outdistanced the other elements. Almost immediately we were sent east again at a terrific pace and liberated the beautiful Duchy of Luxembourg, from which country we penetrated the Siegfried Line, and, according to the newspaper, were the first division to enter Germany. Now we are in Belgium and no longer at liberty to say exactly where or what doing. But I can tell you the relative inactivity, the sunless skies, the deep mud, and the obvious unfriendliness of civilians are beginning to be most unpleasant though for a couple of weeks, the rest was a great relief after such a punishing millrace. But, at its very worst, this theatre has been far pleasanter than Panama ever was at its very best. I shan't try to analyze why this is so, but probably the greatest reasons are positive action, tangible results from our sacrifices, climate, and above all superior generalship.

In the medical line, we have been at times intensely busy, of course, and I have been thankful to have a hand in pouring in the plasma and the sulfanomides. Because of the speed of our advance, my echelon has had almost no opportunity to do any real surgery as we had anticipated, but with dauntless ambulance drivers, we've been able to get the lads back in time for better surgery and better facilities behind us. Furthermore, we have been blessed with a relatively light casualty list and much we had feared in anticipation has fortunately never materialized. For quite a long time I treated more Germans than our own, which I camtell you, was perfectly all right with us in view of the reason!

I can't begin to tell you all of my impressions during this period of combat. The first few days in France among the ruins of Isiguy, Carentau, Montebourg, and St. Lo; then the beautiful August weather and its dust (figure what an armored column does to a dusty road not rained on for three weeks; and at high speed!); the uniformly well-fed, frenzied, but mendicant French people; the flat and uninteresting terrain; the striking beauty of Luxembourg and the less frantic but possibly more sincere greeting from its citizens; the pathetic empty forts of the Maginot Line; the time I (a city slicker from Brooklyn) bought a heifer for the company so that we had a week's relief from interminable K and C rations; the cold—and later very hot—reception we got by contrast in Germany; the laughable Nazi propaganda directed at us by radio; the discomfort of enemy shellfire; how to dig a foxhole; and finally the interesting attitudes and ideas of the wounded prisoners. I must confess that the problem of reeducating the S.S. and younger Nazis appears colossal from here, but the other prisoners are mostly pathetic and far from being supermen. They all know the jig is up all right and they're all glad to be out of it, but few of them know enough facts to know what it's all about or why, except of course for the reasons provided by Herr Goebbels.

LIEUTENANT F. W. NICHOLS JR.,

'42, AUS, describes the Siegfried Line inGermany in a few well chosen words.(Dated February 17, 1945.)

We are practically sitting in the middle of the Siegfried Line. It is a massive line of defense constructed of steel and concrete. Pillboxes, dragon teeth, and antitank ditches are all around us, some with gaping holes and others in ruins. Among some prisoners taken from some of them were several young women, a few in uniform and others in civilian clothes. We have heard several stories of the Germans having concubines in their garrisons, but have never seen them as part of a frontline defense. But I guess morale is more important to Jerry. My CP is now in a small German town that is battered to a pulp, and there are no civilians. When this war comes to an end some of these towns are so greatly damaged that the people would do better to build their new homes in a different locality.

This certainly is a queer world! Here we are over here shelling and bombing all these towns, cities, bridges, blowing up dams; destroying power plants. And then when peace is declared we will lend our services (probably manpower, but certainly our vast resources) to rebuild Europe again. And if we are not careful this time, your son and mine may have to come over again and do what we have had to do. But I hope that my son's education will not include that.

LIEUTENANT (jg) E. SMEDLEY

WARD has seen plenty of destroyer action in the Pacific and I think you will findthis short letter packs quite a punch.

Things have been fairly quiet for us these past few weeks—in fact, the fleet (except for the 7th) hasn't seen much surface action since we ran into the Nips during the latter part of October. Our big menace at present is suicide planes. They are raising hell and the difficult thing is that they are hard to stop. In addition, some of the pilots are pretty clever. One recently found himself enclosed in flak bursts and threw his plane into a spin. However, just before the dive, he threw out a dummy in a parachute—the ship's gunners thinking that it was all over, ceased firing. Much to their surprise the plane straightened out a few hundred yards over the water and dove into a carrier.

Our biggest worry at present is the abundance of typhoons. In fact, we are in port now repairing a damaged gun mount that was practically torn off in the heavy seas off Formosa.

I see that the War Department has just released the story of three destroyers which ran out of fuel, capsized and sank in a particularly fierce typhoon off Luzon. Herb, it is hard to realize how devastating these typhoons can be, if you haven't experienced one. Undoubtedly, you remember the New England hurricane of '39add mountainous waves and a crazily pitching and rolling ship and you'll partially have what one is like. They have done more damage to our fleet than the Japs. We were extremely fortunate not to lose more ships in the typhoon I just mentioned.

The seas were so rough for about a week that many of the smaller ships couldn't fuel at sea, therefore when the typhoon changed course suddenly, it found many ships in its path that were practically helpless. The Spence, capsized and water en- tered her stacks and blew up her boilers. I believe five of her personnel were rescued. To be frank, I had visions of hanging my Xmas stocking over the side of a lifecraft myself. The velocity of about twenty feet combined to make a situation which will long be remembered. I can't describe or emphasize too strongly the formidability of these tropical storms when encountered in a small ship. I'll take the Nips any timel

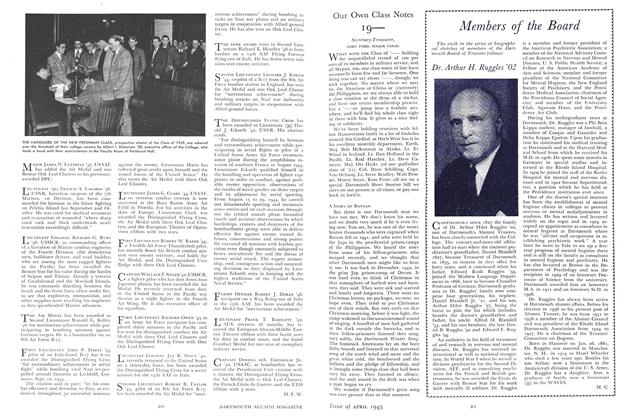

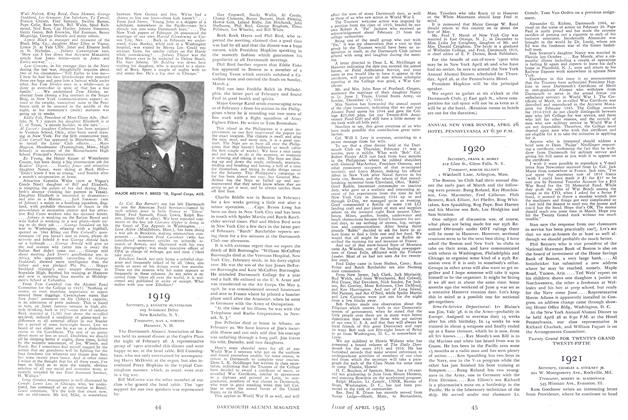

IN THE DRIVE ACROSS EUROPE, the division of Corp. Jack Petrequin '35 was the first armor to enter Paris and the first to enter Germany. His cousin, Bud Petrequin '25, sent in the above picture.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

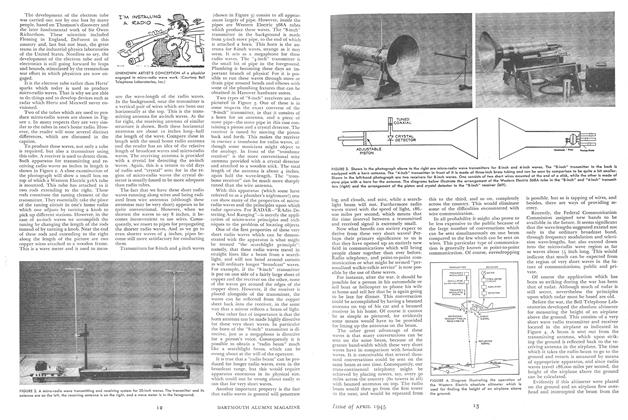

ArticleRADIO WAVES AND RADAR

April 1945 By GORDON FERRIE HULL JR. '33, -

Article

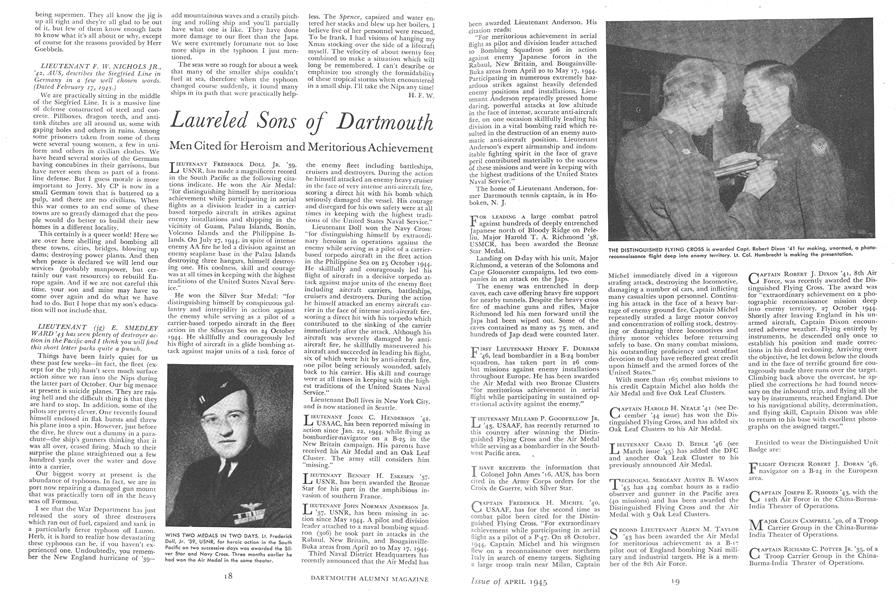

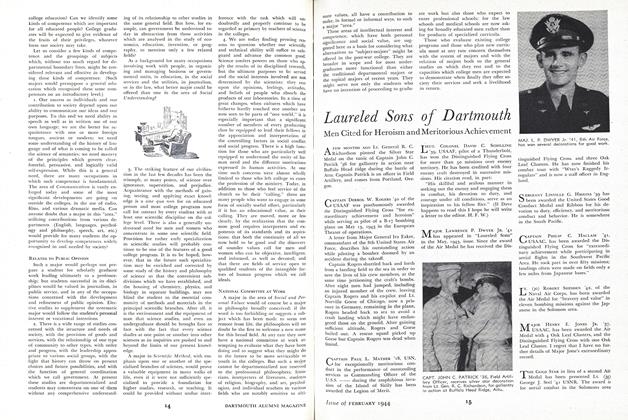

ArticleLaureled Sons of Dartmouth

April 1945 By H. F. W. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

April 1945 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1945

April 1945 By ARTHUR NICHOLS -

Article

ArticleMedical School

April 1945 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1919

April 1945 By J. KENNETH HUNTINGTON, MAX A. NORTON

H. F. W.

-

Article

ArticleLaureled Sons of Dartmouth

December 1943 By H. F. W. -

Article

ArticleLaureled Sons of Dartmouth

February 1944 By H. F. W. -

Article

ArticleLaureled Sons of Dartmouth

May 1944 By H. F. W. -

Article

ArticleLaureled Sons of Dartmouth

March 1946 By H. F. W. -

Article

ArticleLaureled Sons of Dartmouth

June 1946 By H. F. W. -

Article

Article25 Years Ago

May 1947 By H. F. W.

Lettter from the Editor

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

FEBRUARY, 1927 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorFor opinions which appear in these columns the Editors alone are responsible

May 1929 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

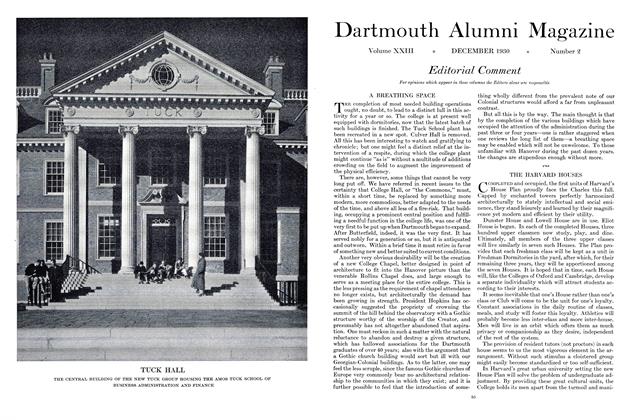

DECEMBER 1930 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

APRIL 1932 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorOn Being No. 1

MARCH 1984 By Douglas Greenwood -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorSome Thoughts on Commencement, 1985

June • 1985 By Douglas Greenwood