"I wish I could tell you about the South Pacific," James A. Michener wrote in the beginning of Tales of the South Pacific. For me, it is one of the memorable openings in American literature, one which reveals as much about the narrator's inability to recreate the past as it does about his wistfulness, his self-consciousness, his attempt to tell a story - any story - with some semblance of verisimilitude. I was reminded of this line as I sat down for the third or fourth time to write this little essay out of a sense of my own frustration in telling you about the College we both call alma mater.

It began over lunch at the Faculty Club with an alumnus whom I knew but vaguely when we were undergraduates. He is now a member of the Dartmouth faculty, teaching government and Afro-American studies, and finishing a major book on Nigerian political history. We were meeting to discuss an article he might do for the Magazine, and I can remember walking back into Blunt after lunch thinking that he should write at least five different pieces for us. When he talked about how good the students are here, about his most recent trip to Africa, about the faculty's involvement in the governance of the College, about the significance of "the liberal arts" in a small, liberal arts college his eyes sparkled; he reminded me of a young boy who has found a bag full of precious stones that he wants to share with you. Call it a flight of fancy on my part, but that was the image I came away with.

His odyssey from Dartmouth to the wide, wide world, and back again reads like one of Scheherazade's tales a Fulbright to study at the University of Grenoble, then a Rhodes to study at Oxford, followed by a position at UCLA, a return to Oxford for the Ph.D., intermittent teaching in Nigeria and Khartoum, and finally, an- invitation to teach at Dartmouth. I thought about my own trek through academe, how very predictable it was that I should go to universities on the East coast and write a dissertation about a Dartmouth man and I said that to him and he replied, "Well, I suppose mine was very predictable, too." He went on to talk about what he called the two Dartmouths that were here in the early 60s the one many of us knew, with rowdy fraternities and the camaraderie begot of long winters on the Hanover Plain, undefeated football teams, road trips to Skidmore and Paradise Pond - and the one he sought out mainly via the Dartmouth Christian Union. In those days, the DCU had probably more to do with political activism than with any formalized religon; it was the place the campus radicals, such as they were, called home. And without the guidance and encouragement of the DCU's George Kalbfleisch, my friend recalled, he might well have given in to his impulses to head South and work for SNCC, leaving the relatively quiet scene at Dartmouth behind, and perhaps not finishing up here at all.

His words reminded me not to generalize too much about the Dartmouth experience, about what, with the passage of time, may seem to be universal to men and women of the same generation. After leaving my college mate, I wandered over to the plaque outside Parkhurst Hall to read the Reverend Lucius Waterman's "Prayer for Dartmouth College." It says, in part, "Give to its teachers the gift of teaching, and make them be men right-minded and high-headed." We would have to add women to that prayer today, but we could hardly improve on the wording, or for that matter, on my luncheon companion's commitment to Dr. Waterman's fondest wish.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

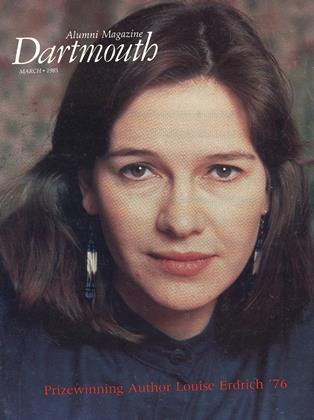

FeatureIntimate Collaboration

March 1985 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureWHY STUDY EVOLUTION?

March 1985 By Warren D. Allmon '82 -

Feature

Feature"I have Nineteen Thousand. Do I hear Twenty?"

March 1985 By Douglas Greenwood -

Sports

SportsRecruiters' haul

March 1985 By Jim Kenyan -

Article

ArticleDynamite

March 1985 By Alice Dragoon '86 -

Article

ArticleRandom Thoughts

March 1985 By Gayle Gilman '85

Douglas Greenwood

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorVisions and Revisions

SEPTEMBER 1983 By Douglas Greenwood -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorThe Fall of '63

November 1983 By Douglas Greenwood -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorThe Real World

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Douglas Greenwood -

Article

ArticleFootnotes on an Annual Report

MAY 1985 By Douglas Greenwood -

Article

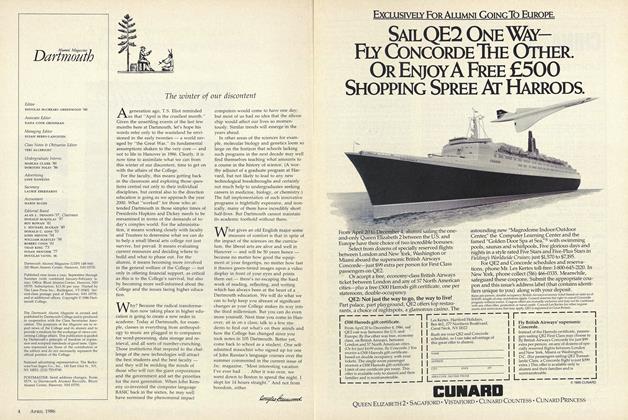

ArticleThe winter of our discontent

APRIL 1986 By Douglas Greenwood -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the Editor"Only Connect..."

MAY 1986 By Douglas Greenwood

Lettter from the Editor

-

Lettter from the Editor

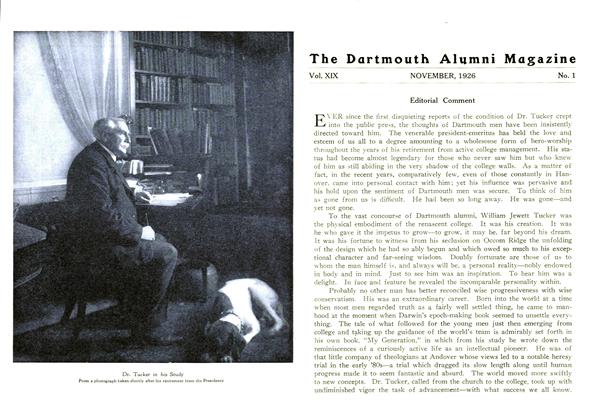

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

NOVEMBER, 1926 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

DECEMBER 1927 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

MARCH 1931 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the Editor'Round the Girdled Earth

May 1944 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorIn Keeping With This Month's Cover Story, The Review Barks Up Dartmouth's Tree.

MAY 1992 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorWhy We Run "Cause" Advertising

MAY • 1988 By THE EDITORS