The Atom Bomb Is No Exploding Cigar, as the Public Seems to Think, Says Dartmouth Alumnus Who Saw Bikini Tests as Member of Army-Navy Press Staff

"THIRTY SECONDS TO FIRINGTIME"The final switches have been thrown.No one can stop it. .... T-he Atomic Bombis about to explode"TWENTY FIVE SECONDS ""How it will sound we do not knowForty-two thousand men are watch-ing"TWENTY SECONDS "

It had all been scripted five days before. The seconds ticked off and we were "on the nose"; the timing was perfect. Since Baker Day minus Three the radio reporters had rehearsed their cues. And the fates were with us; our signal from Bikini to the States was loud and clear.

"We are about ten miles away

"FIVE .... FOUR .... THREE ....TWO . . . .ONE

The engineer opened the underwater mikes and we waited.

There was a strange hissing sound. We weren't certain. We waited and listened.

It must have been eight or nine long seconds. Then the underwater hammer struck the hull of the Mount McKinley. And for the first time in the broadcast control room we knew it had gone off.

That was what an underwater atomic bomb sounded like. The engineer rode the gain to full volume and then faded . . . . the cue for Admiral Blandy's official announcement that the world's fifth atomic bomb had been detonated.

This was Test Baker of Operation

CROSSROADS: 0835 Bikini Time, 25 July 1946 (East Longitude Date).

Our 15-minute broadcast reached the States on Wednesday afternoon. The ratings showed that not many people listened and we understand that Bikini's second atomic explosion, while a prominent front-page story, did not get "the play" in the newspapers accorded Test Able on July 1.

The atomic bomb was here to stay. The American public was long aware of it in news o£ the United Nations proceedings, and now that it had been handled gingerly like a big firecracker in the first Bikini test, it was a pretty dead story.

This reaction was interesting to us at Bikini, for practically all of the dire predictions of catastrophe, the fantasies which helped to promote the near-hysterical interest in CROSSROADS, had centered around the underwater atomic explosion, Test Baker.

But the American public had heard and read the reports of Test Able, and the impression had been that the A bomb was, in the reported words of a Russian observer, "Not so much."

The complex story of CROSSROADS is still being written. It is being gathered in hundreds of photos, in graphs and instrument readings, in detailed reports and in the thinking of the top directors of the operation and in the analysis of the evaluators. Much of the story, in the interests of national security, will never be told.

What most of us know about momentous and remote events in the modern world is "only what we read in the papers." And what most of you in the States know about CROSSROADS depends largely on what particular paper you read.

When I talk to people here about their impressions of the atom bomb tests and recall what I witnessed at Bikini I know the story has not been accurately conveyed.

What follows are essentially my personal observations of the coverage of CROSSROADS, principally Test Able, as a member of the public information staff of Joint Army-Navy Task Force One.

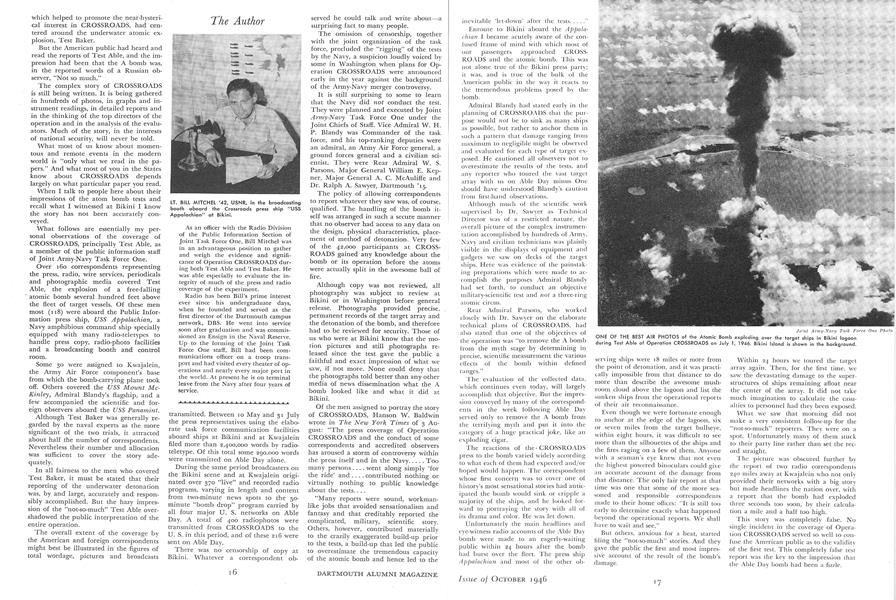

Over 160 correspondents representing the press, radio, wire services, periodicals and photographic media covered Test Able, the explosion of a free-falling atomic bomb several hundred feet above the fleet of target vessels. Of these men most (118) were aboard the Public Information press ship, USS Appalachian, a Navy amphibious command ship specially equipped with many radio-tele types to handle press copy, radio-photo facilities and a broadcasting booth and control room.

Some 30 were assigned to Kwajalein, the Army Air Force component's base from which the bomb-carrying plane took off. Others covered the USS Mount McKinley, Admiral Blandy's flagship, and a few accompanied the scientific and foreign observers aboard the USS Panamint.

Although Test Baker was generally regarded by the naval experts as the more significant of the two trials, it attracted about half the number of correspondents. Nevertheless their number and allocation was sufficient to cover the story adequately.

In all fairness to the men who covered Test Baker, it must be stated that their reporting of the underwater detonation was, by and large, accurately and responsibly accomplished. But the hazy impression of the "not-so-much" Test Able overshadowed the public interpretation of the entire operation.

The overall extent of the coverage by the American and foreign correspondents might best be illustrated in the figures of total wordage, pictures and broadcasts transmitted. Between 10 May and 31 July the press representatives using the elaborate task force communication facilities aboard ships at Bikini and at Kwajalein filed more than 2,400,000 words by radioteletype. Of this total some 290,000 words were transmitted on Able Day alone.

During the same period broadcasters on the Bikini scene and at Kwajalein originated over 370 "live" and recorded radio programs, varying in length and content from two-minute news spots to the 50-minute "bomb drop" program carried by all four major U. S. networks on Able Day. A total of 400 radiophotos were transmitted from CROSSROADS to the U. S. in this period, and of these 216 were sent on Able Day.

There was no censorship of copy at Bikini. Whatever a correspondent observed he could talk and write about—a surprising fact to many people.

The omission of censorship, together with the joint organization of the task force, precluded the "rigging" of the tests by the Navy, a suspicion loudly voiced by some in Washington when plans for Operation CROSSROADS were announced early in the year against the background of the Army-Navy merger controversy.

It is still surprising to some to learn that the Navy did not conduct the test. They were planned and executed by Joint Army-Navy Task Force One under the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Vice Admiral W. H. P. Blandy was Commander of the task force, and his top-ranking deputies were an admiral, an Army Air Force general, a ground forces general and a civilian scientist. They were Rear Admiral W. S. Parsons, Major General William E. Kepner, Major General A. C. McAuliffe and Dr. Ralph A. Sawyer, Dartmouth '15.

The policy of allowing correspondents to report whatever they saw was, of course, qualified. The handling of the bomb itself was arranged in such a secure manner that no observer had access to any data on the design, physical characteristics, placement of method of detonation. Very few of the 42,000 participants at CROSSROADS gained any knowledge about the bomb or its operation before the atoms were actually split in the awesome ball of fire.

Although copy was not reviewed, all photography was subject to review at Bikini or in Washington before general release. Photographs provided precise, permanent records of the target array and the detonation of the bomb, and therefore had to be reviewed for security. Those of us who were at Bikini know that the motion pictures and still photographs released since the test gave the public a faithful and exact impression of what we saw, if not more. None could deny that the photographs told better than any other media of news dissemination what the A bomb looked like and what it did at Bikini.

Of the men assigned to portray the story of CROSSROADS, Hanson W. Baldwin wrote in The New York Times of 3 August: "The press coverage of Operation CROSSROADS and the conduct of some correspondents and accredited observers has aroused a storm of controversy within the press itself and in the Navy Too many persons went along simply 'for the ride' and .... contributed nothing or virtually nothing to public knowledge about the tests....

"Many reports were sound, workman-like jobs that avoided sensationalism and fantasy and that creditably reported the complicated, military, scientific story. Others, however, contributed materially to the crazily exaggerated build-up prior to the tests, a build-up that led the public to overestimate the tremendous capacity of the atomic bomb and hence led to the inevitable 'let-down' after the tests. .

Enroute to Bikini aboard the Appalachian I became acutely aware of the confused frame of mind with which most of our passengers approached CROSSROADS and the atomic bomb. This was not alone true of the Bikini press party; it was, and is true of the bulk of the American public in the way it reacts to the tremendous problems posed by the bomb.

Admiral Blandy had stated early in the planning of CROSSROADS that the purpose would not be to sink as many ships as possible, but rather to anchor them in such a pattern that damage ranging from maximum to negligible might be observed and evaluated for each type of target exposed. He cautioned all observers not to overestimate the results of the tests, and any reporter who toured the vast target array with us on Able Day minus One should have understood Blandy's caution from first-hand observations.

Although much of the scientific work supervised by Dr. Sawyer as Technical Director was of a restricted nature, the overall picture of the complex instrumentation accomplished by hundreds of Army, Navy and civilian technicians was plainly visible in the displays of equipment and gadgets we saw on decks of the target ships. Here was evidence of the painstaking preparations which were made to accomplish the purposes Admiral Blandy had set forth, to conduct an objective military-scientific test and not a three-ring atomic circus.

Rear Admiral Parsons, who worked closely with Dr. Sawyer on the elaborate technical plans of CROSSROADS, had also stated that one of the objectives of the operation was "to remove the A bomb from the myth stage by determining in precise, scientific measurement the various effects of the bomb within defined ranges."

The evaluation of the collected data, which continues even today, will largely accomplish that objective. But the impression conveyed by many of the correspondents in the week following Able Day served only to remove the A bomb from the terrifying myth and put it into the category of a huge practical joke, like an exploding cigar.

The reactions of the • CROSSROADS press to the bomb varied widely according to what each of them had expected and/or hoped would happen. The correspondent whose first concern was to cover one of history's most sensational stories had anticipated the bomb would sink or cripple a majority of the ships, and he looked forward to portraying the story with all of its drama and color. He was let down.

Unfortunately the main headlines and eye-witness radio accounts of the Able Day bomb were made to an eagerly-waiting public within 24 hours after the bomb had burst over the fleet. The press ship Appalachian and most of the other observing ships were 18 miles or more from the point of detonation, and it was practically impossible from that distance to do more than describe the awesome mushroom cloud above the lagoon and list the sunken ships from the operational reports of their air reconnaissance.

Even though we were fortunate enough to anchor at the edge of the lagoon, six or seven miles from the target bullseye, within eight hours, it was difficult to see more than the silhouettes of the ships and the fires raging on a few of them. Anyone with a seaman's eye knew that not even the highest powered binoculars could give an accurate account of the damage from that distance. The only fair report at that time was one that some of the more seasoned and responsible correspondents made to their home offices: "It is still too early to determine exactly what happened beyond the operational reports. We shall have to wait and see."

But others, anxious for a beat, started filing the "not-so-much" stories. And they gave the public the first and most impressive account of the result of the bomb's damage.

Within 24 hours we toured the target array again. Then, for the first time, we saw the devastating damage to the superstructures of ships remaining afloat near the center of the array. It did not take much imagination to calculate the casualties to personnel had they been exposed.

What we saw that morning did not make a very consistent follow-up for the "not-so-much" reporters. They were on a spot. Unfortunately many of them stuck to their party line rather than set the record straight.

The picture was obscured further by the report of two radio correspondents 240 miles away at Kwajalein who not only provided their networks with a big story but made headlines the nation over, with a report that the bomb had exploded three seconds too soon, by their calculation a mile and a half too high.

This story was completely false. No single incident in the coverage of Operation CROSSROADS served so well to confuse the American public as to the validity of the first test. This completely false test report was the key to the impression that the Able Day bomb had been a fizzle.

To set the record straight here, this is what the bomb did on Able. Day: 2 destroyers, 2 transports and tile' Japanese cruiser Sakawa sunk; practically all ships within three-quarters, of a mile damaged, most severely enough to be "out of action," including the carrier Independence, the battleships Nevada and Arkansas and the cruiser Pensacola.

The underwater bomb on Baker Day: carrier Saratoga, battleship Arkansas, Japanese battleship Nagato, a concrete oil barge and 2 submerged submarines sunk; a concrete dry dock and an LCT so severely damaged that they were later destroyed by demolition. The survey of damage to hulls and interior fittings of other ships still continues.

These figures do not take into account the tremendous physical and psychological problems posed by the extensive radioactivity encountered aboard target ships, particularly in Test Baker. They represent a summary report of the results of a singleatom bomb in each test.

The most significant and least sensational story of Operation CROSSROADS at Bikini was that it had been realistically planned with imagination and foresight; it had been efficiently executed without serious casualty to any of the 43,000 participants; and it had been well started towards accomplishing the main purpose of determining in measured, scientific terms the effects of the atomic weapon on naval and military targets not previously exposed.

The reports of CROSSROADS to the public did not seriously impair any of the primary objectives of the operation, but subsequent events may record the confused and irresponsible impressions communicated to the world as one of the most tragic junctures in history.

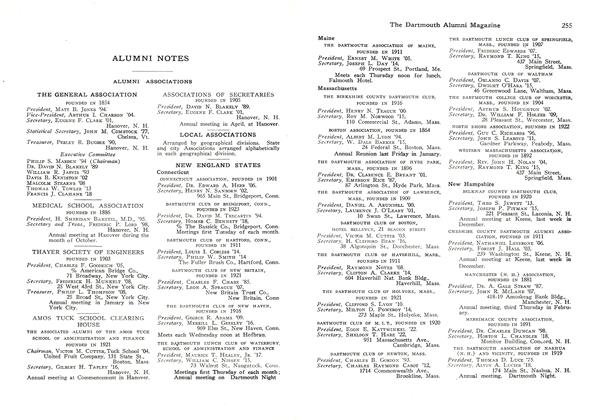

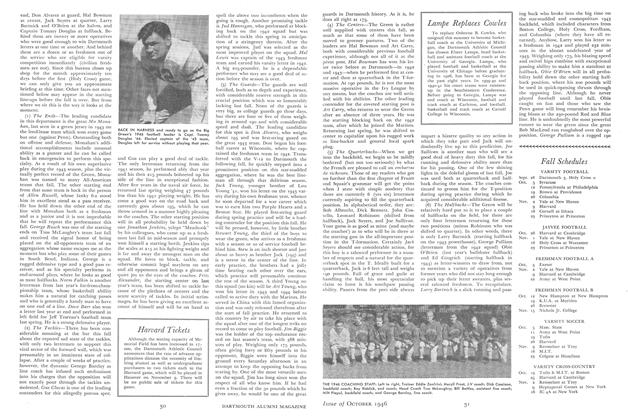

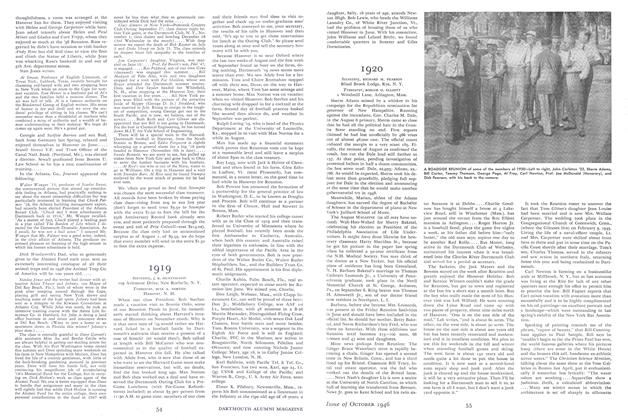

ONE OF THE BEST AIR PHOTOS of the Atomic Bomb exploding over the target ships in Bikini lagoon during Test Able of Operation CROSSROADS on July 1, 1946. Bikini Island is shown in the background.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Sports

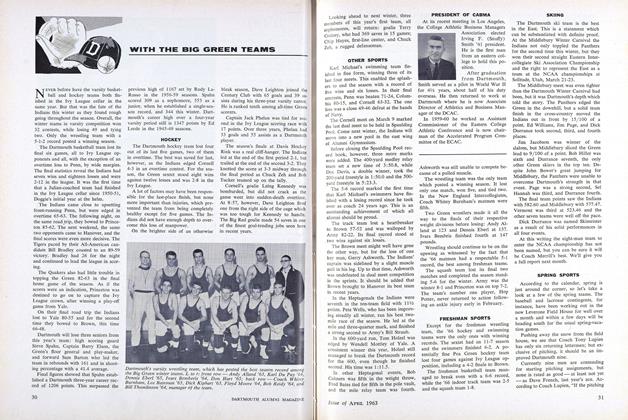

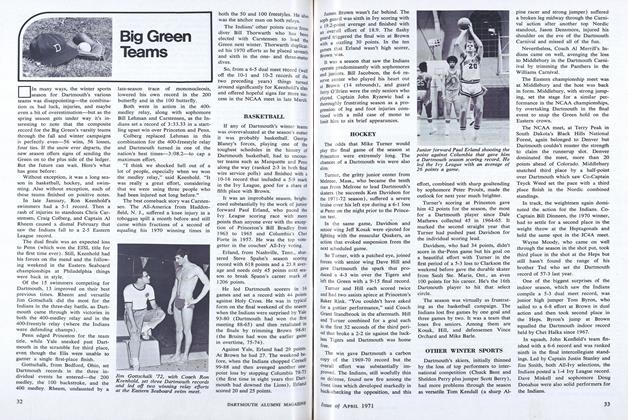

SportsWith Big Green Teams

October 1946 By Francis E. Merrill '26 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917

October 1946 By MOTT D. BROWN, DONALD BROOKS, SUMNER B. EMERSON -

Article

ArticleThe Coming "Boom and Bust"

October 1946 By BRUCE W. KNIGHT -

Article

ArticleCan We Achieve Economic Stability?

October 1946 By JAMES F. CUSICK, -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

October 1946 By ERNEST 11. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

October 1946 By RICHARD B. KERSHAW, WILLIAM C. WHIPPLE JR., JULIUS A. RIPPEL