Is THE AFTERMATH of the Second World War, the editors ask, to consist in part of an impressive "boom and bust"? Yes—probably. Not, however, the early sequence on which popular attention centers today. The early jolt is more likely to be a mere left jab: a brief boom followed by a sharp but short recoil. It is not until after a jab or so has been weathered that the authoritative right to the jaw is to be expected: a long and exuberant upswing succeeded by a deep and durable depression. But first a word on the prediction of human behavior, for that is the clue to the story.

Where communion with the burning bush is ruled out, prediction proceeds on the principle that the same things will behave in the same way under the same circumstances. The special difficulty of predicting social occurrences is that the "things'" and "circumstances" are largely human beings who are affected by experience. Recalling what happened before, we usually try to behave at least somewhat differently next time. Hence prudence is needed in using the device of "compensating errors," which assumes that future deviations to one side of an established norm will be offset by others on the opposite side. For men are always capable of stacking their deviations on one side, thus establishing a new norm, perhaps a better one. Prediction in the social "sciences," therefore, is not just a science, a projection of known averages into the future. It requires also a judgment of what men with memories and records are likely to do to the averages.

Consequently the present problem raises two main questions. First, what has been our experience with postwar ups and downs? Second, what has the experience probably taught us? I ponder these things, and they do not comfort me.

So far, great depressions have appeared in the wake of great wars. Further, the really great ones have been so belated as to put men off guard concerning this particular result of war. The sequence of events has been roughly this: First, a wartime boom, with easy money and full employment, which continued or recurred for a short time after the war. Second, a severe but short-lived setback, with some deflation. Third, a lengthy period of prosperity, with an investment boom, a resumption of easy money, much speculation, and a burgeoning of the belief that the "new era" has come to stay. Fourth, a profound and prolonged decline, marked by heavy deflation, a withering of investment and foreign trade, disastrous unemployment, and the theory that the other sort of "new era" has begun, all followed by social convulsions variously termed "revolutions" and "new deals." The sequence is illustrated by what happened after the Napoleonic Wars, our Civil War, and the First World War. Comparatively brief depressions followed these conflicts by respective periods of five years, a few months, and something over two years. For the long and terrible depressions, however, the corresponding intervals were about ten years, eight years, and eleven years.

The character of the path ahead of us today depends on what such experience has taught us. That is, what have we learned about the reasons for the exceptional violence of late postwar depressions, in the sense that we are really preparing to amend our social habits? For purposes of this inquiry, the best point of departure is the worst depression on record: that which hit the United States some eleven years after the First World War.

As a distinguished British economist observed, The Great Depression resembled an earthquake. That is, the damage was ascribable, on the one hand, to the violence of the shock, and, on the other, to the instability of the structure which was shaken. It was not strange, after the greatest war in history, that the economy should be badly out of balance. As the leading belligerents had shifted about half their total productive power from peace to war, the road back could not be other than a long one. The prodigious power of the shock arose from the fact that, once the removal of wartime controls had permitted the resumption of the familiar "business cycles," a particularly big cyclical upswing was allowed to develop. Much of the blame for this must be put on the war and the methods of financing it. The war created a severe postwar shortage of capital goods, partly by direct destruction, still more by diverting productive power to types of equipment which were largely useless in a peace economy. At the same time the quantity of money, greatly swollen by government borrowing from banks, was maintained after the war because banks expanded their loans to business by about as much as they contracted their loans to government. In an economy dominated by individual enterprise, the combination of deficient real capital and redundant dollars was a reasonably sure-fire recipe for an excessive investment boom. Such was the general picture. With respect to the question of learning from experience, we can afford to consider somewhat more specifically certain factors which contributed to that boom and bust.

First, a "new era" psychology developed. It came to be widely supposed that the business cycle, which had been suppressed by the abnormalities of war, was a thing of the past. Indeed, a President of the United States contributed to the general scolding which bankers and academic economists received for their "outmoded" theories on the subject. What of the future before us now? If we are to have once more the general sort of economy which we had before the war, we shall again have business cycles, including cyclical downswings. And of course we are going to have that sort of economy. Then will the incandescent optimism of the 1920's, that cavalier contempt for the "ivory tower" of the economist, return to ride us to another fall? Unfailingly, at least once every generation, and certainly after every great war, it has always done so in the past. And before long now, I think, we can expect to hear that "there is nothing to fear but fear," and that those dreary "true-in-theory-but-not- in-practice" fellows, die economists, would better go and mind their own business- whatever that is.

Second, the ravages of war, together with the unusually rapid technological changes of the 1920's, served to upset demand and supply relations from industry to industry and from region to region. Matters were made worse by futile attempts to collect foreign debts while using trade barriers to deny debtors the means of payment. What of today's future? Although we shall doubtless refrain from trying to collect much on lend-lease, it is certain that the second great war was indefinitely bigger than the first and that it must have left something like correspondingly greater maladjustments behind it. As for the prospect of technological changes, we need not peer around the next corner for "the atomic age." Nevertheless it is pertinent to brand as hokum the notion that our economy is "senile" in the sense that past changes decrease the chance of future changes. On the contrary, inventions and discoveries breed more of their kind. We must not trust to any decline of scientific progress to simplify the task of postwar readjustment. Further, we must expect that growing rigidities in the economy—monopolistic prices, labor-union and employerassociation wages, a mounting ratio of fixed to working capital, and forms of government intervention inspired by politics rather than economics—will complicate the job.

Third, the huge boom which promoted the great depression was encouraged by hasty relaxation of government wartime controls, notably production priorities, price ceilings, and consumer rationing. Although America's haste may not have occasioned major and lasting harm after our first general war, similar haste cannot let us off easily after the second. Since it was necessary to use these controls for upwards of two years in order to effect a full conversion of our economy from peace to war, it stands to reason that we should not, soon after the close of the military war, just let go and turn over to private enterprise the unprecedented task of reconverting the economy back to peace. We need price ceilings as a safeguard against price inflation. More of that anon. We need priority control to direct productive power into capital goods—to get a better balance between production goods and consumption goods before individual enterprise takes over. Priorities and ceilings together would help controlled readjustment also by channeling money into production goods and away from consumption goods. Even if our moral obligation to millions of innocent sufferers abroad were not mentioned, price ceilings call for rationing as a means of preventing a squalid scramble for goods at home. In the face of these needs, what have we? Priorities and rationing mostly gone, and price ceilings jubilantly on their way. Thus private enterprise is invited to restore order to a radically deranged economy—an undertaking for which it is not equipped.

Fourth, our great boom of the 1920's was fed by a vast supply of bank-created dollars. Now, after our second great war, in order to get an enlarged edition of the same general result, it is not necessary for the banks to create more dollars. We already have three spendable dollars for every one we had in 1939. The trouble might be dated from the time when Senator ("Dear Alben") Barkley walked out in a huff at the suggestion that Congress was relying too little on taxes and too much on loans. However, now that we have borrowed too much in general and too much from banks in particular, what next? We must eschew the seductive notion, propounded by a Dartmouth alumnus distinguished enough for something better, that extra production will take care of the extra dollars. A trebling of 1939 production is not imminent. Even if we brought it off, those trebled dollars, plus a shortage of capital goods, plus individual enterprise, still point to a disorderly investment boom. Then what else have we for the control of actual monetary inflation and potential (and actual) price inflation?

The Federal Reserve system might help by making it more costly and difficult to borrow from banks. But actually it cannot do much as long as our other and more powerful monetary authority, the Federal Government, is set on low interest rates as a means of holding down the cost of its own borrowing.

Business, labor, and government might contrive to avoid wage advances which, by raising some price ceilings, evoke demands for other wage increases, and so on. But government and labor together—and they have been together—are more powerful than business. Perhaps we could manage to relax the huddle a bit. And here just a word on the Reuther proposition that wages should be raised to protect national "purchasing power." If purchasing power means power to purchase, it should be noted that national purchasing power can be increased only by increasing national production, a feat which is not accomplished by prolonged stoppages" of production. If it means money—the idea being that more money would increase national production—the fact is that we have far too much money already. This is not all that is wrong with the doctrine, but it is enough for present purposes.

A "buyers' strike" is a forlorn hope. It would have to be highly organized. It won't be. What is more likely is that buyers, on the whole, will buy early to avoid the rush.

There are numerous things which the Federal Government might do. Although some changes in relative prices are in order, it might preserve general price ceilings until increases of production and decreases of money render such ceilings unnecessary. But compare this with the unvarnished deeds of the summer of 1946! It might use large amounts of revenue from heavy taxation to pay its debts to banks, which hold about two-fifths of its total debt of some $275 billion. This would reduce existing bank money at member banks while curbing the power of Reserve banks to help members create more money. However, the "Dear Alben" case was a sufficiently eloquent symbol of Congressional attitude toward heavy taxation. Any threatened influx of money from abroad might be stemmed by a lowering of our import barriers against foreign goods. Here, some help, but not much, may be expected from our reciprocal trade program, and from the new mechanism of the international fund and bank, although the former is exposed to the mercy of Congress every three years while the control of the latter has national governments behind the scenes. The Government might deflate by shifting its balances from member banks to Reserve banks, by demanding gold certificates from Reserve banks, or even by reversing the devaluation of the dollar. All in all, its anti-inflation arsenal looks imposing enough. However, after a decade and a half of deficit finance, and during the heyday of the "purchasing power" prescription for curing what ails us, the prospect that the weapons will be used vigorously is not bright.

The makings of a postwar "boom and bust" are greater than ever before. So, too, are the available means of prevention. But is it probable that we are sufficiently awake —our government, and ourselves as voters and influencers of voters and government —to employ those means resolutely? As this is a prediction, and not a pep-talk, my conclusion is: No. No, we shall probably act, for all practical purposes, as if the cure were worse than the disease, and we shall therefore get the disease. When we get what we are asking for, no doubt our views on comparative badness will undergo startling revision. But that is another story.

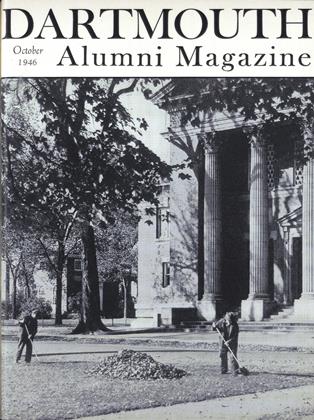

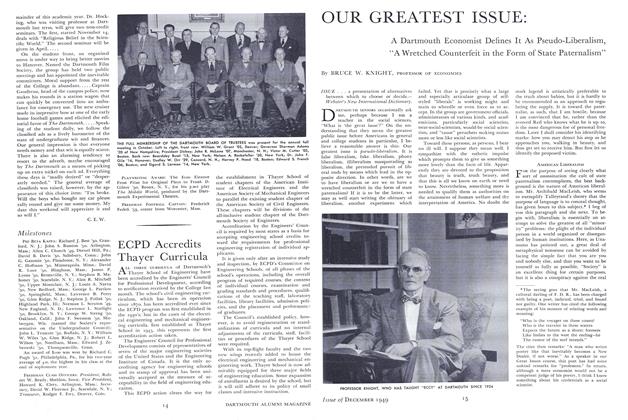

A CLASSROOM PICTURE of Prof. Bruce Knight, who finds disturbing signs that this country has forgotten many of its last postwar lessons.

PROFESSOR OF ECONOMICS

Bruce Knight, who came to Dartmouth's Department of Economics from the University of Wisconsin in 1924, is a specialist in the economics of war. He is the author of the book, How to Runa War, which Knopf published in 1936, and in the following year he organized at Dartmouth the first general course on war offered in the country. He is co-author of a two-volume textbook, Economics (1929); and in 1938 he had published his Economic Principles inPractice, which was revised in 1942: Professor Knight is a veteran of World War I, which interrupted his career as student and teacher in Texas and Oklahoma. After the war he took his B.S. degree at the University of Utah in 1921, for the next two years taught economics at the University of Michigan, and then for one year taught at the University of Wisconsin before coming to Dartmouth. He has been a full professor since 1934 and now teaches courses in "Economic Problems" and "The Economics of War."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Sports

SportsWith Big Green Teams

October 1946 By Francis E. Merrill '26 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917

October 1946 By MOTT D. BROWN, DONALD BROOKS, SUMNER B. EMERSON -

Article

ArticleOPERATION CROSSROADS

October 1946 By WILLIAM J. MITCHEL JR. '42 -

Article

ArticleCan We Achieve Economic Stability?

October 1946 By JAMES F. CUSICK, -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

October 1946 By ERNEST 11. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

October 1946 By RICHARD B. KERSHAW, WILLIAM C. WHIPPLE JR., JULIUS A. RIPPEL

BRUCE W. KNIGHT

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

FEBRUARY 1932 -

Books

BooksMOBILIZING CIVILIAN AMERICA

July 1940 By Bruce W. Knight -

Article

ArticleOUR GREATEST ISSUE

December 1949 By BRUCE W. KNIGHT -

Books

BooksTHE RETURN OF ADAM SMITH

April 1950 By Bruce W. Knight -

Books

BooksAN INTRODUCTION TO ECONOMIC REASONING.

June 1956 By BRUCE W. KNIGHT