BACK IN THE MIDDLE of July when the Class of 1915 was holding its de- layed 30th Reunion, there was a tall, white-haired, ruddy-faced man who kept up his own personal reuning long after the '15 tent was quiet and deserted. Someone said he didn't sleep for the first three nights he was in Hanover. This much is true—every night for the week he was here he was out on campus until the early hours of morning recapturing familiar scenes he had not seen since his graduation and learning the outlines of the many new buildings that had sprung up since his undergraduate days. A year in a German concentration camp and two more hiding with the French Maquis had made his return to Hanover more meaningful to him than just an ordinary reunion.

I met "Jiggs" Donahue by chance and arranged an interview for the following day, picking the handy, familiar clearing house—the Inn porch—for a meeting place. Once we were settled in lawn chairs near the porch in a quiet, cool corner, he gave me the bare chronology of his life following graduation. Full name, Arthur I. Donahue, Class of 1915; wife, Elizabeth Theris, a French woman he met following World War I; assistant manager, then manager of Gillette Razor's Paris branch from 1926-31; assistant manager of Colgate-Palmolive-Peet, Paris, -1931-March, 1940; general manager of the same concern, March 1940-December is, 1941.

On December is, 1941, two hours after the Germans declared war on the United States, Jiggs Donahue was arrested by the Gestapo, along with all other American male nationals in Paris. Everyone but the women and children disappeared into the shadowed land of concentration camps, and even they were to follow less than a year later.

"They took us first to the Cite Universitaire the University of Paris—where we were kept for three days. Then we were loaded into buses and moved to Compeigne, 50 miles north of Paris."

Here, in what was formerly a French aviation camp, they made their last stop. Large and fairly modern, the camp had one-story barracks equipped with running water. The latter was the sum total of the creature comforts. This was their home.

"In the dead of winter the buildings were virtually unheated—one day's supply of wood had to last a week. We suffered terribly from the cold all winter, but particularly during the first two months when we had only the food that the Germans gave us. A cup of herb tea in the morning; thin, watery soup with a few shreds of carrots or turnips in it at noon; and another cup of herb tea and a wedge of black bread at 5 p.m. On fare like that, we felt-the cold more severely. Finally, on the 15 th of February, we were allowed one parcel per month from our families and, about the same time, the Red Cross packages began to arrive. I can honestly say that without them we would have been hard put to survive."

For the first 15 days after they were imprisoned, the- Germans allowed them no communication with the outside, not even a form letter telling their families where they were. Eventually, they were permitted one visit every two weeks from their families or friends. In the same camp, separated from the Americans and a handful of Russians and Serbs by a double row of barbed wire, were two to three thousand French Communists and 2000 French Jews, the real objects of German penal methods. They were allowed no parcels or visits, and practically no letters, were given no heat and were forced to keep their barracks windows open. Their beds were a half-inch of straw on the cement floors with one blanket per person.

"Their rations were so poor I saw many a Jew look as badly as the horror camp inmates. This was just a way-station for them—they were bound for Belsen, Buchenwald, Dachau, Auswitz."

Under the Geneva Convention agreements, the American internees did not have to work; they were allowed to spend their time as they wanted insofar as the camp facilities afforded. Originally this consisted of walking, lying in bed and reading. To supplement this meager recreational program, they used an empty barracks as a club and made card and ping-pong tables for it. Outdoors they set up a small baseball diamopd, a basketball court, a tennis court, some earthen bowling alleys, horseshoe pits and gymnasium equipment. There were a few books available from the American Library in Paris, all light novels or detective stories. A few prisoners studied languages under Russian professors interned with them. They held their own concerts, both symphony and jazz.

"The worst aspect of the internment was its effect on our morale. We were living as simple soldiers without any opportunity to get out of ourselves, without being able to break away from the severe regimen. Continually behind barbed wire, under strict surveillance, seeing the same people day after day, having no news of the war—it was so bad that two Americans went crazy, as did many more of the Communists and Jews. Overnight, we had been wrenched from our usual habits and customs, and from our families and friends and forced into a drab, seemingly endless pattern.

"After I had been a year at Compeigne, my wife became seriously ill. At first they wouldn't let me out, but finally, on application of my wife's surgeon, I was given a furlough from internment, under the following conditions: My wife should be examined regularly by a German physician; I must report regularly to the police; and I must not move from Paris. As my wife's condition improved, I thought of breaking my furlough, for I was sure that this time they would also take my wife to prison camp.

"About this time a friend of ours, a police inspector whom I suspected of being a member of the Underground, came and told us that the Gestapo had recently been making inquiries concerning us and intimating that they would soon be picking us up. He advised escape, and furnished us identification cards in the names of Mr. and Mrs. Duchesne. Along with these, he introduced us to another member of the Resistance Movement who in turn gave us the name of a third member in St. Laui ent-du-Pont, a village in southeastern France, 18 miles from Grenoble.

"Fortunately, I had put pur apartment in a nephew's name in 1940 and he had since sub-let it to a friend, so that our Paris trail was well covered. We hastily packed and 24 hours later were on a train for what was formerly the Free Zone of France. Our decision to head there, in addition to the help offered by the Underground, was based on the fact that the Germans had not had enough troops to occupy this zone completely, but concentrated in the main centers of population. Our tensest moment of the trip was when the train stopped at Chalon-sur-Soane and a German officer boarded to inspect identity papers. When he came to our compartment, ,1 pretended to be half asleep and allowed my wife to hand over our papers. He studied them for a long moment and scrutinized us closely. After what seemed a lifetime, he handed them back with a tres bien and left.

"Once in St. Laurent-du-Pont, I went to the address of M. Marechal, the man to whom we had been directed by the Paris Underground. He greeted us with considerable reserve and suspicion and questioned me closely. When I was able to give him the address and business of the Paris intermediary, he acccepted us warmly and showed us every kindness. After a short consultation, he found us a hiding place up the road at a farm in the little village of St. Joseph-de-Rivere. The farm was owned by a rich M. Boursier, who was head of the Maquis of the Plain.

"Outside of a few of the younger men, who were engaged in running messages to Marseilles, Lyons, Paris, and even to Switzerland, distributing clandestine newspapers and periodicals, and perpetrating occasional acts of sabotage, there was very little apparent activity on the part of the Maquis. However, underneath this deceptive appearance, this area was a hotbed of resistance. Pro-Germans or pro-Vichyites were in constant danger of their lives, to say nothing of the jeopardy of having their farms and homes burned. Everyone in the movement was constantly drilling and practising in secret for the invasion, when they would mobilize to blow bridges and throw up road blocks in the rear of the retrea'ting Germans. Actually this never happened for the invasion of southe rn France came sooner and moved much more swiftly than we anticipated.

"Even though I was immediately appointed chef-de-group of this Maquis Reserve due to my experience and training in World War I with the Yankee Division, I felt -I did exactly nothing. I will never forget the members of the Corps Franc, the bravest of the brave, the most reckless members of the Resistance movement. They were all former members of the Chasseurs Alpins, the Blue Devils, the mountain troops of the French Regular Army. Groups of four in Citroen cars would circulate morning and night with machine guns and tommy guns bristling from all sides and small FFE fanions mounted on the mud guards, blowing up tunnel entrances and bridges, and harassing any small body of German troops they met. I came to know one particular group well because they had a gas cache at a mountain farm where I eventually lived.

Two of them were later killed in a battle at Grenoble with the Germans after the Americans had landed. No words of praise are too great For these men or for the Secret Agents, who never capitulated but continued to work from Vichy itself. My opinion is that they were the founders of the Underground and the most valuable members of it, for they had professional experience and the advantage of having their headquarters in Vichy with ramifications in the various government services. They not only got information but they undermined Petain and the Vichyites as well as the Germans, and were probably responsible for the fact that Petain's personal bodyguard left him en masse when de Gaulle called for the uprising.

"Lisette and I changed hideouts four times before the liberation, principally because we began to suspect certain persons of being informers, later learning our suspicions were well justified. Eventually we landed in the mountains and were luckily there when the Germans twice came into the plain with 1000 men and raided all the farmhouses. They burned the Boursier farm where we had been staying and took M. Boursier away with them. He was never heard of again.

"One day in early September, following the raids, we heard the sirens wailing and the bells ringing. We thought it was the Germans coming again and we hid in the mountains, ready to fight if necessary. When we found it was an American patrol, it was the signal for the greatest outburst of delirious joy and release I have ever witnessed. We had been waiting for so long and the tension had become so great that we found it hard to realize that it was all over.

"The four American soldiers never completed that patrol. They were feted, wined and dined; speeches were made in their honor and speeches given in reply; an impromptu parade formed about their jeep with beautiful girls swarming all over it. I took them back to their headquarters in Grenoble and offered my services to their commanding officer, but they were declined. When I returned to St. Laurentdu-Pont I was in time to see the most glorious sight of the Resistance and the Occupation. Truckload after truckload of armed and trained Maquis from the mountains—at least 2000 of them—were rolling through the square on their way to Grenoble. As they went by singing the Marseillaise at the top of their lungs, roaring to get into action, I thought of them as I had seen them many times up in the mountains, cold, half-starved, but never losing faith, always waiting for this daythe day of revenge for all the oppression they suffered during four long years. They represented the real France, the one.that had never capitulated.

"Thus ended four years of the Occupation for my wife and myself, for we were soon on our way back to Paris and our apartment. I might say that although many a time I regretted my decision to stick it out in Paris until the last moment, I nevertheless would not have wanted to miss this whole experience. And I would like to add that anything that was hard for me was infinitely harder on my courageous wife, Lisette, who was seriously ill throughout all these hardships, but who took the privations and the pain with stoicism and understanding."

Jiggs Donahue was suddenly called back to Paris on September 8 because of a crisis in his wife's condition. Lisette Donahue, a brave woman, died in Paris on September 28.

FIRST STEP IN PRESENTING THE STORY of Jiggs Donahue 'l5 (right) is taken by James L. Farley '42, assistant editor of the "Magazine", who interviewed the former French Underground member during his' Hanover visit.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

Article"JEFF" TESREAU

November 1946 By EDWARD JEREMIAH '30 -

Article

ArticleADVOCATE OF PLENTY

November 1946 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917

November 1946 By MOTT D. BROWN, DONALD BROOKS -

Article

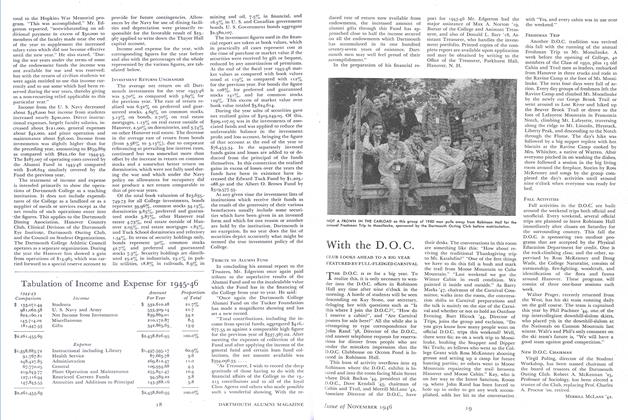

ArticleAnnual Financial Report

November 1946 -

Article

Article188 Sons of Alumni Among Entering Students This Fall

November 1946 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1915

November 1946 By SIDNEY C. CRAWFORD, CHANDLER H. FOSTER

James L. Farley '42

-

Feature

FeatureThe Boom in Off-Campus Study

NOVEMBER 1970 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Books

BooksPhiloprogenitive Man

December 1975 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Article

ArticleFair Arm of the Law

January 1977 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Feature

FeatureCommencement

JUNE 1977 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Article

ArticleCommencement

June 1981 By James L. Farley '42 -

Books

BooksExpanding the Dream

JAN.- FEB. 1982 By James L. Farley '42