Shattuck Observatory, Little Changed During the Past 92 Years, Has a Rich Tradition of Scholarship and Scientific Advancement

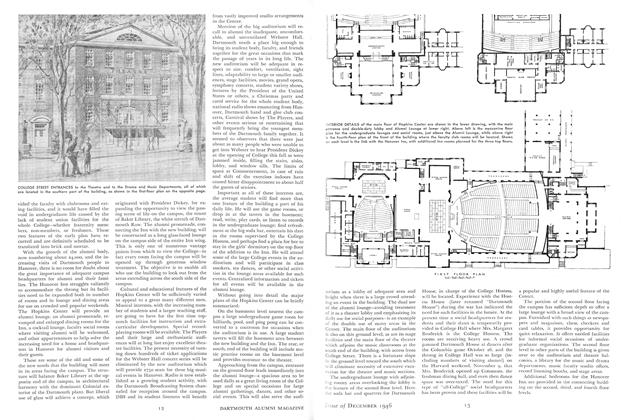

HIGH UP OVER HANOVER, commanding a view especially prized by those who know it well, is Dartmouth's Shattuck Observatory, the only building in the College, except the Medical School, which remains essentially the same strucure that it was when it was built. Except for the green shutters which have been added and the disappearance of the old pine tree which stood not far away, it looks as it did 92 years ago when Dr. George Shattuck, 1803, of Boston had it built as his gift to Dartmouth.

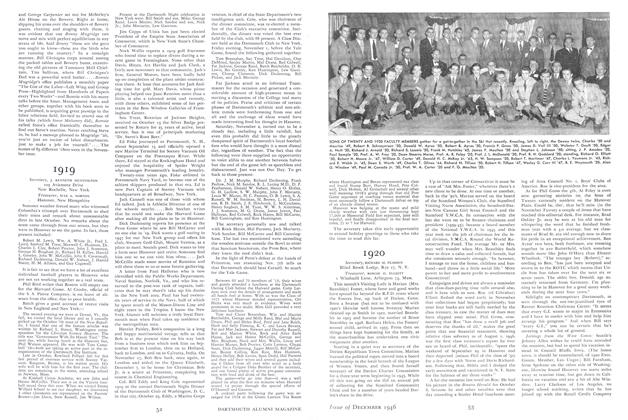

Yet in spite of the increasing handicaps in size and equipment (which reached a maximum during the war, when the Department of Astronomy taught in a period of five years over six thousand man-semesters), the Observatory has maintained a tradition distinguished for scholarship and original research. Added to this, perhaps because the wit and humanity of John Poor still haunt the rooms or because those students who lived there rent free in return for making weather observations somehow domesticated it, the Observatory has a homelike quality all its own. The present Director, Prof. Richard H. Goddard '20, has perpetuated this human, if intangible, quality of ease and humor combined with work, which is very real to anyone visiting the Observatory today.

One of the first pieces of scientific apparatus to be owned by the College was the orrery, brought from London with a "standing telescope with achromatic glasses" by Eleazar Wheelock the younger, in 1784. The orrery was intended to demonstrate the relative motions and positions of the members of the solar system. It is said that Professor Adams, who taught Natural Philosophy, a subject which included astronomy, refused to have the orrery mended because to do so would spoil his annual joke—that the "moon was acting loony." By John Poor's time both equipment and the standard of jokes had greatly improved.

Besides the instruction in astronomy, which goes back as far as 1782, the Observatory has the record of the longest series of weather observations in New Hampshire. Precipitation records are complete for over one hundred years.

The earliest recorded meteorological observations made at Hanover, so far as is known, were by Ebenezer Adams in 1827-28, and included the temperature and state of the weather. From 1834-39 Professor Adams observed precipitation as well as temperature "morning, noon, and night."

In 1834 upon the representations of Prof. Ira Young, 1828, that the scientific apparatus then on hand was inadequate and largely outdated, funds were appropriated for the purchase of equipment. He desired particularly to acquire "an altitude and azimuth instrument, a good telescope, a sidereal clock and micrometer," which ( to quote from his report) involved the "germ of a small astronomical observatory." The telescope was obtained from Merz of Munich. As there was no observatory, this telescope was set up on a rude frame in Professor Young's garden. The circles, clock drive and micrometer could not be employed and the instrument stood in great danger of injury.

From 1841-47 Professor Young observed barometric pressure, temperature, clouds, wind direction, and precipitation at his weather station. Thus it can be said that the solid foundations of both astronomy and meteorology at Dartmouth were laid in Professor Young's garden.

In 1849 a small observatory, 28 by 13 feet, was erected in Professor Young's garden. It was divided into two rooms, one furnished with a pier and a sliding roof for the telescope, and the other with two piers and an opening through the roof and sides for the transit instrument. This room was plastered and had the comfort of a stove and "other conveniences for a computing room." A lively interest in the study of astronomy was awakened among the students, so that the instruments were in almost constant use.

Professor Young was a driving force in the history of the Observatory. He was well known as a "born teacher" and for having outstanding patience with undergraduates. His popularity and the interest he aroused in astronomy led to Dr. Shattuck's gift of the Observatory in 1854. Dr. Shattuck also financed a trip to Europe for Professor Young and his son. They returned with instruments and scientific books, the most important additions being "a two and onehalf foot meridian circle with a five-foot telescope; a comet seeker of four inch aperture; a pocket chronometer; Newman's standard barometer." They were installed, with the 1848 telescope, in the nearly completed building, where the meridian circle, Newman's standard barometer, and the comet seeker are still in use today, the latter as a guide on the present equatorial instrument.

After Professor Young's death in 1858, James W. Patterson, 1848, became Professor of Astronomy and Meteorology, and was in his turn succeeded eight years later by Charles A. Young, 1853, Appleton Professor of Natural Philosophy and Astronomy. Professor Young's work in the Shattuck Observatory was the foundation for his later fame among astronomers. He was a brilliant scientist with a devotion to his subject which animates his own writings and all the records which have come down about him. He was one of the first scientists in the country to believe that the layman can and should know facts in specialized scientific fields.

It was during the great eclipse of the sun which he observed at Burlington, lowa, that Professor Young made his observation of the "reversing layer," a thin sheet of gases enveloping the sun. This discovery was fully confirmed 25 years later by Shackleton, by means of a photograph of the "flash spectrum."

In the September 1869 issue of TheDartmouth, Professor Young describes his observation of the eclipse, with a vividness which recalls that of some of the observers of the first trials of the atomic bomb. He wrote:

"The moon hung in the sky, dark though not absolutely black. Fastened upon her edge there seemed to be several stars, of color like the planet Mars. Around her was the mysterious Corona. .... I cannot tell what it was that made the spectacle so impressive. The attempt to put it into words evaporates it. I only know that its effect was overwhelming—as if I had been admitted to the immediate presence of the Creator. It was a moment worth hours, perhaps years, of ordinary life."

Observatory equipment was increased during Professor Young's service and within a few years there came that series of discoveries which placed him at once among the most distinguished astro-physicists of the world and brought the Observatory an international reputation. Dartmouth suffered a great loss when he left to go to Princeton, where opportunities for research were greater.

Of Professor Young, C. H. Bouton '78 wrote years later: "There seemed to be always a smile upon his face and often a sparkling of the eyes None who ever studied under Professor Young could wonder that the nickname 'Twinkle' clung to him. It was particularly appropriate to him, both as an astronomer and as a man.

From 1877 to 1892, Prof. Charles F. Emerson '68 carried on the work in astronomy and physics. He was succeeded by a young man who studied under Professor Young and later became one of America's greatest astronomers—Edwin Brant Frost '86. Frost, who held the professorship in astronomy at Dartmouth from 1892 to 1898, was the brother of the late Dr. Gilman Frost '86 of Hanover. Both the Frost brothers spent their boyhood days in Hanover and Edwin Frost's autobiography, An Astronomer's Life, gives a witty and engaging picture of the Hanover of his time. He left his work at Dartmouth to be Director of the Yerkes Observatory at the University of Chicago. In his later years, Frost became blind, and Bouton recalls of him then: "One night the roof of the observatory was rolled entirely off, giving a full view of the sky. Professor Frost felt along the polar axis of the mounting, stepped directly back, and I saw him point to stellar positions as accurately as he could have done had he been able to see. The heavens were in his mind."

Following Professor Frost, Prof. John M. Poor '97 headed the Department from 1898 until his death in 1933. His research on comets, asteroids and double stars won him prestige among astronomers over the world. Although no one ever heard of it from Poor himself, he was awarded, among other honors, membership in the British Royal Academy. Not even his closest friends knew of the many deeds of kindness he performed, and which came to light only after his death.

The great scope of his interests first of all mathematics, but covering English literature, the classics, ancient history, music, political science—afforded his students a richness of knowledge far beyond the formal limits of his courses.

In Professor Poor's time the hospitality of the Observatory was extended to a few choice friends, both town and gown. The janitor on certain Sunday evenings would make oyster stew, and Professor Poor made coffee which, according to Dr. Leland Griggs of the Zoology Department, "was supposed to take the varnish off the chair you were sitting on when you drank it. If that didn't happen, Poor put the coffee back on the stove and boiled it for another hour."

Professor Griggs also recalls the time he was in the Observatory when a student came with the persistently repeated request to Poor that he be given a B in the course. Poor finally said, "All right," erased in his book, and wrote another mark. When the student left, Professor Poor remarked to Griggs, "It's too bad that boy wanted a B so badly. I had to change it from an A."

In 1904 Professor Poor increased the equipment of the Observatory by the addition of a transit instrument and zenith telescope, and in time secured other instruments which greatly improved the usefulness of the Observatory for students.

Since Professor Poor's death, the department has been headed by Professor Goddard. In 1935, the weather station was enlarged and modernized. Since that time the meteorological program has grown to include continuous recordings of barometric pressure, relative humidity, wind direction, wind velocity, precipitation, and sunshine. Hourly tabulations of prevailing wind direction, wind velocity, sunshine, and precipitation are made and the results are transmitted monthly to the United States Weather Bureau. For the completeness of its records, the Shattuck Observatory ranks in the State with the U. S. Weather Bureau station at Concord and the Mount Washington Observatory.

A description of the Observatory would be incomplete without mention of the student weather observers who, until 1925, lived in the building. There were rumors that some of them were less conscientious than others. Charles Sumner Cook '79, who was later an instructor in the Department, wrote:

"My duties were three-fold. Astronomical sunspot sketches, and an occasional shot at the stars with the transit to get the time for the electrical control of the college clock in the tower of Dartmouth Hall. Meteorological full observations, three times a day. Curatorial keeping things polished up; the floors, the windows, the instruments and the handle of the big front door. There are some foundations for the rumors that certain of my predecessors were in the habit of 'observing' but once a week and that they filled out the records from data afforded by memory, probabilities, precedents, surmises and assumptions all adjusted with a considered judgment."

In 1934-35 the north wing of the Observatory was made over into a small seminar and class room. In 1938 another telescope intended primarily for the use of student observers in courses, was designed, made, and given to the Shattuck Observatory by John W. Lovely, Dartmouth 1937. This instrument, an 8-inch reflector, with its well engineered equatorial mounting, setting circles, and synchronous motor drive, was housed in another small white brick building, and continues to be a most satisfactory teaching instrument for class use.

The Observatory next procured a 3-inch Ross type lens astrographic camera with synchronous motor drive, which early in 1939 was mounted in the building formerly occupied by the 5-inch Clark refractor. But as the war loomed, the gradually increasing pressure of enrollment in the courses in naval orientation and celestial navigation shifted the emphasis of the activities of the Observatory until with the advent of the Navy V-ia Unit in July 1943 the entire augmented staff was engaged in the program of the preparation of officer candidates for the naval service. The meteorological program was however continued, even though analysis of data was frequently, during the war years, as much as five months behind.

From September 1940 through June 1945 the time and energy of the staff of the Shattuck Observatory were devoted more and more and finally completely to the teaching of courses specifically designed to prepare men for duty in the armed forces. A list of courses taught will indicate the diversity of the fields: under the Civil Pilot Training Program, ground school courses in meteorology, air navigation, civil air regulations and aircraft operation; under the regular college curriculum from January 1942 through June 1943, celestial navigation, meteorology, and naval orientation; under the Navy V-12 program from July 1943 through June 1945, celestial navigation and naval organization.

One of the great rewards of the Observatory's work in the war was the pouring in of hundreds of letters from Navy men all over the world who profited by the wartime courses offered by this department of the College. There were approximately one hundred men in the Civil Pilot Training Program, over one thousand in celestial navigation, and approximately five thousand in naval orientation and organization.

The Department of Astronomy was able to obtain last spring the services of Prof. George Z. Dimitroff, who came to Dartmouth from the Oak Ridge Observatory Station of which he was superintendent, and which he himself largely built up, at Harvard, Mass. He received his Master's and Doctor's degrees in astronomy at Harvard.

In Edwin B. Frost's autobiography he wrote of the vast change in man's conception of the universe which has been brought about by the work of the astronomers in the past half century. In that advance Dartmouth astronomers have taken an active and distinguished part, as evidenced by the six starred names in American Men of Science.

The Shattuck Observatory has a tradition to be proud of, and when it acquires the enlarged facilities to keep pace with a college enrollment seven times larger than the 350 men of its earliest days and with the rapidly expanding science which it serves, it will have an equally great hope for the future.

In the meantime, its students and staff have borrowed from Admiral King the motto posted in most of the Observatory rooms: "Do the best you can with what you have."

IN ITS EARLIEST DAYS the Shattuck Observatory looked like this. Except for white paint and minor additions it appears much the same today.

PRESENT DIRECTOR. Prof. Richard H. Goddard '20, now head of the Shattuck Observatory, scans some of the complete weather recordings made there.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleHOPKINS CENTER

December 1946 By SIDNEY C. HAYWARD '26 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

December 1946 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1928

December 1946 By OSMUN SKINNER, RUPERT C. THOMPSON JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1919

December 1946 By J. KENNETH HUNTINGTON, MAX A. NORTON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917

December 1946 By MOTT D. BROWN, DONALD BROOKS -

Class Notes

Class Notes1935

December 1946 By H. REGINALD BANKART JR., FREDERICK T. HALEY