A VERY WISE MAN once gave me a gloomy warning about the Aims of Youth. -"Be careful what you decide you want when you're young," he said, "you're very apt to get it when you're older," and he was quite right. He also gave me this rather epigrammatic advice, with an implication I (innocently) missed: it doesn't matter what you are; it only matters what you become. Now this "becoming" would seem to be a matter of maturation in a propitious environment, something which implies the operation of what we call education; as a matter of fact, we can consider that education is just this process of becoming—which is certainly as unrestricted a definition as you could wish for, and one that covers practically every kind of learning experience.

The fact that I am prosecuting education and the improvement of the mind by entering Dartmouth as a first-term freshman at the advanced age of twenty-four would have seemed a good deal more incongruous before the war than it does now. Let me tell you how it came about.

First of all, I graduated from high school in 1938 (which is a long time ago), confronted with a decision between college and learning an immediately renumerative trade (advertising and industrial design) at the Franklin School of Professional Arts in New York. Being sixteen, about as worldly as Snow White, not too clear about directions in general, and of a resolutely self-supporting disposition, I chose (not unwisely) the vocational school, thinking to be at twenty in an excellent position with my new trade to know my mind and to put myself into college.

As it happened, it seemed more prudent in the fall of 1941 for young men to direct their attention to the Air Corps than to architecture. I found, however, that eyes a little below 18/20 were a stumbling block, worked for a while in an airparts plant in production and inspection, finally wound up early in 194s in the Coast Guard Reserve, United States Maritime Service. The Maritime is a Government Service administered by the Navy which trains men for the merchant fleet. In those days of the summer of 1942, during the Battle of the Atlantic when German U-boats were sinking a half-dozen ships a day, the Maritime was a likely way to a mate's ticket and a commission in the Naval Reserve.

My experiences at sea and my travels in the world were just like those of thousands of other men; my important work in the Service was on the Sunstill.

A cousin of the late President Roosevelt's, Richard Delano, first had the idea of the Sunstill. He saw dew condense in empty bottles on the beach and on the windows of greenhouses, wondered whether solar energy could be used as power-source to operate a fresh water distiller that could be supplied as safety equipment to men forced down in rafts at sea. At the time I was assigned to the famous SKAT Insect Repellent project at Gallowhur Chemical Corporation; this was a period when there was such a shortage of ships that it was impossible at times to find a berth. George Gallowhur, the head of this company, was the man who had discovered how to apply the principle of a light filter to a sunburn preventive; he was the inventor o£ SKOL and other products dealing with the sun. Delano brought his suggestion to Gallowhur. We all worked on the solar distiller, but I shipped out, of course, as soon as I could.

The next thing I knew I had been taken precipitously from my ship in Perth, Western Australia, and flown home halfway around the world to develop suggestions I had made on the still. Rickenbacker's spectacular raft rescue had made the outfitting of rafts (then entirely unequipped) enormously important; Roosevelt displayed a primitive Sunstill on his desk and Churchill carried one about with him in his briefcase. A development project under a secrecy order was set up at Gallowhur, to which I was assigned by the Maritime. Working furiously, we had the first socalled Model A in production in the summer of 1943.

What is the Sunstill like? There were many kinds of models, round, cylindrical, many-shaped, but in general a Sunstill looks like a kind of blown-up plastic jellyfish, about thirty inches long. The device is as simple to operate as a child's toy (which of course is what took the two and a half years to achieve!) Primed with sea water and set out with a lanyard alongside the raft in the morning, it floats like a bubble on the face of the sea. It packs into a tiny space when deflated and weighs very little. It is not expendable; i.e., it distills pure drinking water indefinitely.

Having had the good fortune to pass several years of such great stimulation, I found myself on V-J Day at the threshold of an entirely likely career, in possession of a certain amount of specialized knowl edge and a small but comfortable reputation. Why, then, go back, to college?

The answer, of course, is that my most efficient and productive activity in the world seems to lie somewhere between cityplanning and architecture, professions which have as their very cornerstone what is called a good liberal education. A firstrate designer (such as Frank Lloyd Wright) must be more than a superlative technician, he must be a philosopher in his own right: to plan the background for a design of life (important words, those!) for others, he must know how to live well himself, must in fact be prodigiously knowledgeable in many fields. Thus to Dartmouth, one reason among many, rather than to a more specialized school.

My focus of interest seems to be circumscribed within the range of a comparatively new field, Industrial Design, a profession full of potential and challenge, unexplored, comparatively unresolved. In other words, my anticipated function in the world will be that of arbiter of form in producing well-designed articles for mass manufacture. This is useful work; viewed sociologically, the work the profession can accomplish in the postwar years in helping plan a new, vigorous American way of life is uncommonly worthwhile and rewarding.

Do I have the requirements for success in this field? Well, I've been to some pains to find out: psychological tests (aptitudes, interests, 1.Q., values-scale, and so forth) help a good deal; having worked over a period of eight years at all sorts of jobs helps knowing what occupations are sympathetic; above all, there is intuition. If these check, required in addition is a love for the mechanics of construction, and the metaphysics of problems of form, and of their representation, and the perfection of geometric dorian design. Add to these tactual and visual sensuality, pleasure in the incredible (which is a Sense of Magic) and some good-humored affectations (which I prefer to think of as a Sense of Theatre) and you have it.

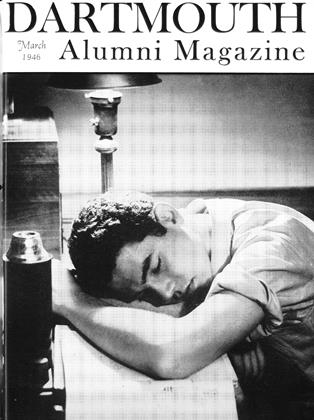

Working on the Sunstill in a very wellequipped plastics laboratory on and off over a period of several years, I was fortunate in being able to develop several plastic products in spare time of a design-invention nature. (This tesm, because in some senses the two words are almost synonymous—good design must be by definition inventive and invention is often entirely a matter of good design). One of these was a lightweight plastic hat-sunshade developed for the Quartermaster Corps to replace heavy, expensive and spacetaking pith helmets in the tropics. It utilized inflation both for excellent deadair-space insulation and to give it its form, which incidentally was of a very stimulating Buck Rogers appearance. Another project was a kayak-type plastic inflated boat, a vast improvement over the famous prewar German "Folbots," designed to weigh only a few pounds and fold into a small suitcase when deflated. The most sensational job was what Time described as "a chair whose fish-net seat (draped over a pneumatic plastic doughnut) was surrealistically adapted to the most unsurrealistic sitter." I had the great good fortune at twenty-two to have the Museum of Modern Art exhibit models of all these things in their fifteenth anniversary show, "Art in Progress."

We used a word with the Sunstill, "Orientation," which described the process by which the face of the still was kept always turned as efficiently as possible towards the activating sun. Some stills needed no orientation, but the most compact designs were productive in direct ratio as they were well orientated. I mention all this because "orientation" is an excellent word to describe the way in which people get their own distilling surfaces, so to speak, turned as efficiently as possible to the activating source; these notes, in fact, describe the process of orientation of one individual to the world, with some emphasis on education, and on Dartmouth College.

I can't tell you whether or not it is an entirely good thing to have come to college at twenty-four; certainly some aspects of college life mean little to the older returned veterans and others are better understood by virtue of maturity. For my own part, having waited four years for college, and having worked hard to get here, I can state with some cogency why I'm here and what I can hope to find; since I regard education, however, as having neither beginning nor end, all experience as more or less instructive, I see Dartmouth as one special (howbeit extremely important) source of education. Other sources, generally encountered after college, have enormous importance. Social environment is one: education among the Athenians, for example, was largely a social affair; the Greek youth formed his ideas naturally and, in a sense, osmotically from contact with older and mellower intelligences. In the Renaissance the master and apprentice system was efficacious in the extreme. Some professions, architecture and law among others, come close to this tradition; the neophyte first works in the office of an established practicioner. After college, I myself would like to work for a while under a self-chosen master.

In general, I believe it is Dartmouth's ultimate mission to impart to her students revelation of two prime spheres of information, information which is prerequisite for successful orientation. One is intrinsic and subjective—self-knowledge. One is extrinsic and objective—knowledge of the culture in which we live.

Today, the necessity for self-knowledge is imposed upon us by society, and transcends the limits of distraction or diversion. In a world of technicians, more and more controlled by categories and card-indexes, we must take every available opportunity to isolate our weaknesses, define the limits of our capacities and predilections, and finally evaluate our potential.

It is equally important that we attain to as profound an understanding as possible of the forces at work in our times and our world-epoch. Each of us must, in the light of all the information he can achieve, formulate his own Weltanschauung, his own world-view. We cannot plan our adjustment to the world in terms of the conditions and values our fathers encountered a generation ago. Mechanization, spreading for a century like a tide over the earth, has accelerated almost in geometrical progression the development of the infinitely complex interpenetrations of social change we see everywhere about us. It is necessary to live and act in the present, and to understand the present. And one must anticipate the day-after-tomorrow to be even up-to-date in such a runaway world.

These two factors, then, must be equated by each one of us and worked together to a solution which brings into rapport our obligations to ourselves as well as to society. Since it is to a great extent within the scope of each one of us to select his environment, the first duty of each man to himself is to determine the environment in which he is most likely to flourish, and to surround himself with it. Adjustment of the man to society is more complex. Certainly, however, it would appear in these times that we should look for more to be got from a college than, for example, a facility with the mechanics of making money. Security, in itself a proper enough consideration, can never again be an ideal. Those of us who remember the economic crack-up of our fathers' world and the unprincipled moral cynicism of the "boom days" which brought it on, those of us who grew up in the disillusion of the depression years, are painfully and gravely aware of the urgent need for new and valid ethics of living. The place to start thinking about these ethics of living is right here at Dartmouth.

Is this a too solemn view to take of things? I think not. The world today is a pretty solemn place. We all come to realize in good time that one cannot live without using such abstracts as "faith" and "honor," although there was a time when such words were a bit embarrassing, like funerals or going to Sunday school. We have before us every morning over the orange juice the one inescapable question: what shall we do now? What is most worthwhile? What is the wisest thing to do?

In a desperate world grown suddenly too small, this question involves more than our selfish interests alone, and we realize the debt every man, particularly men at such a place as Dartmouth, the potential leaders of the next generation, must pay to the world.

I myself believe that a dependable happiness is best based on usefulness, on building, on good work (in my case, on creative work), on social approbation and pride in work well done. I'm staking the boundaries of my little melon-patch here at college and I hope to be happy after college cultivating that melon-patch. I know that Dartmouth will always be a country club to some few of those lucky enough (these days, at any rate!) to be here, and this is proper and natural enough. I know too that my fault is on the side of too much seriousness. I think I would like being a little frivolous for a change. But I am expending on this venture a good deal of energy, money and time, all three precious commodities; above all, I am aware of how much is to be accomplished in the flight of the short days—so you see lam at the end content to remain one of the old graybeards of the campus scene.

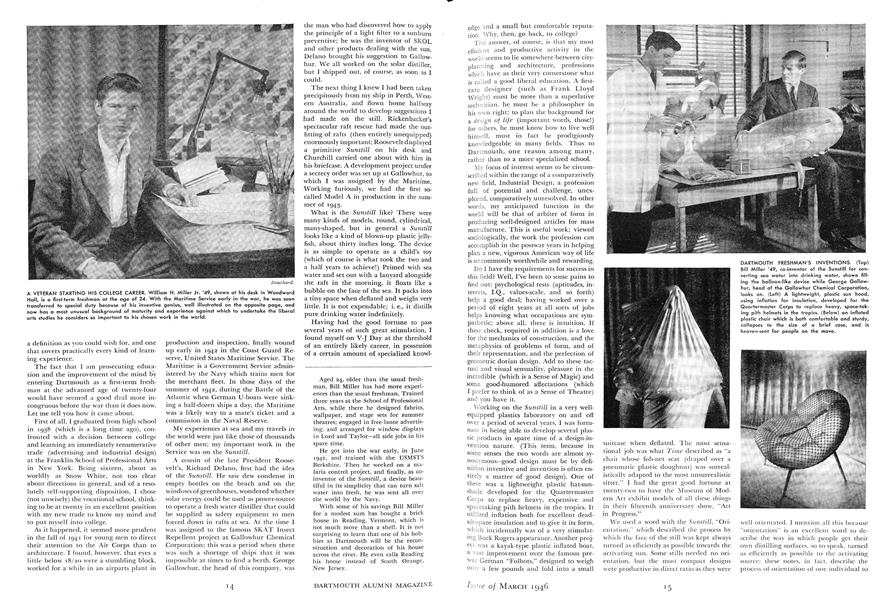

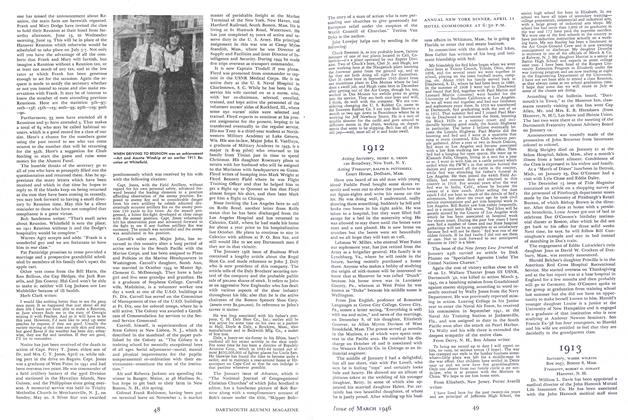

A VETERAN STARTING HIS COLLEGE CAREER. William H. Miller Jr. '49, shown at his desk in Woodward Hall, is a first-term freshman at the age of 24. With the Maritime Service early in the war, he was soon transferred to special duty because of his inventive genius, well illustrated on the opposite page, and now has a most unusual background of maturity and experience against which to undertake the liberal arts studies he considers so important to his chosen work in the world.

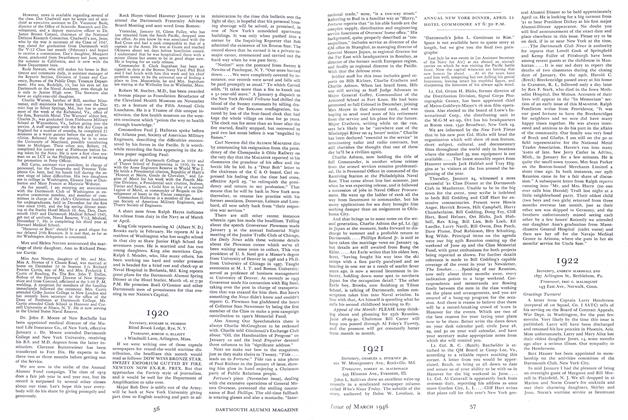

DARTMOUTH FRESHMAN'S INVENTIONS. (Top) Bill Miller '49, co-inventor of the Sunstill for converting sea water into drinking water, shown filling the balloon-like device while George Gallowhur, head of the Gallowhur Chemical Corporation, looks on. (Left) A lightweight, plastic sun hood, using inflation for insulation, developed for the Quartermaster Corps to replace heavy, space-taking pith helmets in the tropics. (Below) an inflated plastic chair which is both comfortable and sturdy, collapses to the size of a brief case, and is heaven-sent for people on the move.

DARTMOUTH FRESHMAN'S INVENTIONS. (Top) Bill Miller '49, co-inventor of the Sunstill for converting sea water into drinking water, shown filling the balloon-like device while George Gallowhur, head of the Gallowhur Chemical Corporation, looks on. (Left) A lightweight, plastic sun hood, using inflation for insulation, developed for the Quartermaster Corps to replace heavy, space-taking pith helmets in the tropics. (Below) an inflated plastic chair which is both comfortable and sturdy, collapses to the size of a brief case, and is heaven-sent for people on the move.

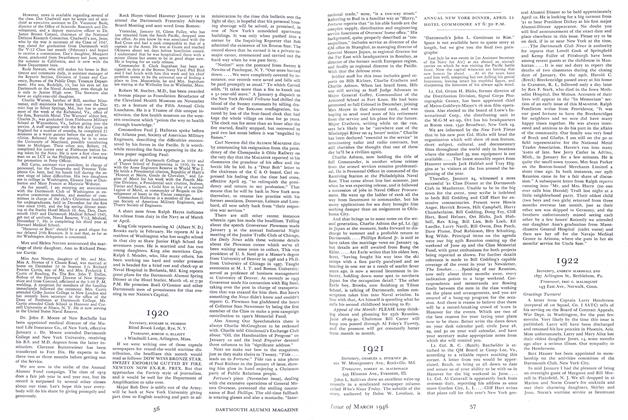

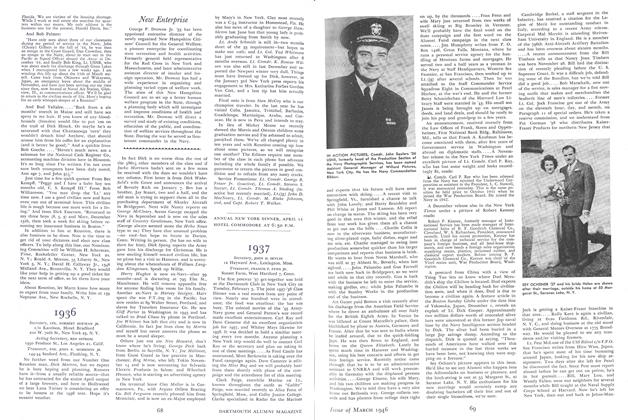

THIS ISN'T THE WAY HE REALLY STUDIES, but Roy Carruthers '42, former Major in the Army Air Corps, does have his wife Mary nearby for moral support as he resumes college studies after five years.

Aged 24, older than the usual freshman, Bill Miller has had more experiences than the usual freshman. Trained three years at the School of Professional Arts, while there he designed fabrics, wallpaper, and stage sets for summer theatres; engaged in free-lance advertising; and arranged for window displays in Lord and Taylor—all side jobs in his spare time. He got into the war early, in June 1942, and trained with the USMSTS Berkshire. Then he worked on a malaria control project, and finally, as coinventor of the Sunstill, a device beautiful in its simplicity that can turn salt water into fresh, he was sent all over the world by the Navy. With some of his savings Bill Miller for a modest sum has bought a brick house in Reading, Vermont, which is not much more than a shell. It is not surprising to learn that one of his hobbies at Dartmouth will be the reconstruction and decoration of his house across the river. He even calls Reading his home instead of South Orange, New Jersey.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

March 1946 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917

March 1946 By MOTT D. BROWN, DONALD BROOKS -

Article

ArticleHANOVER HOLIDAY 1946

March 1946 By PROF. HERBERT W. HILL, -

Class Notes

Class Notes1911

March 1946 By NATHANIEL G. BURLEIGH, EDWIN R. KEELER -

Class Notes

Class Notes1919

March 1946 By J. KENNETH HUNTINGTON, MAX A. NORTON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1934

March 1946 By William C. Emery

Article

-

Article

ArticleCOLLEGE NOTES

February, 1910 -

Article

ArticleTHE PLACE OF ATHLETICS IN AN EDUCATIONAL PROGRAM

February, 1926 -

Article

ArticleCandidates for Alumni Council Election from the New England District

June 1931 -

Article

ArticleTuck School Overseers

June 1962 -

Article

ArticleGive a Rouse for

MARCH • 1987 -

Article

ArticleDEBATERS PLAN ACTIVE YEAR

February 1937 By William B. Rotch ’37