One thing that Hitler destroyed, temporarily at least and perhaps permanently, was the world's reverence for German scholarship. One needs not to have attained the Psalmist's span in order to recall the day when those in quest of: erudite scholarship felt it to be essential to supplement their studies at home by acquiring a degree abroad. It helped to establish one's standing in the educational world if evidence could be shown that one had commanded the approval of such universities as Heidelberg, Leipzig, Bonn, or Goettingen. And not only in such realms as that of chemistry, wherein it was felt that German scholarship excelled. Philosophy, archaeology, divinity and literature made almost equal claims. American students thronged German lecture halls, quite as enthusiastically as they sought out the Sorbonne, or the ancient quadrangles of Oxford and Cambridge.

That's all gone, now. It is not, moreover, entirely the result of war's destruction, which has annihilated many of the tools of the educational trade, such as libraries of books and scientific laboratories. The damage, possibly irreparable, done to the very fabric of German scholarship by the Nazi regime, has been great. At the moment no student from outside would be more likely to seek out Heidelberg than to supplement his studies by courses at Padua, Bologna, or Salamanca. Oxford and Cambridge may still appeal, for one takes a modest pride in writing "Oxon" or "Cantab" after his M.A. Many in all probability will continue to frequent the lecture halls of the Sorbonne. But for the moment the book-burning Nazi has ruined the German universities where once American students gloried—and drank deep.

One result has been the surprising number of applications for admission to American colleges, from countries which formerly thought it best to educate their young in Europe—notably the South and Central American states. China, of course, has long been an avid seeker of American training; but now one finds a host of others—Egypt, Iraq, and the whole Near East, not to men. tion India, Norway and even France. For the nonce it would seem that the once popular German university is "out." Hitler's attempt to put German thought in Nazi fetters was a crime against the world of knowledge; but most of all a crime against Germany herself since it annihilated what was Germany's most valid claim to greatness—her painstaking scholarship.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1915

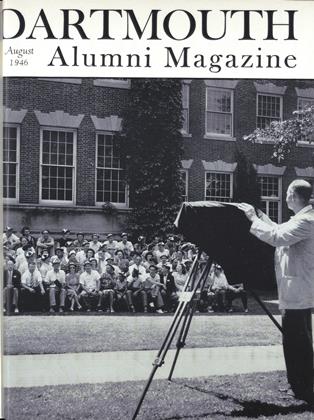

August 1946 By SIDNEY C. CRAWFORD, CHANDLER H. FOSTER -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

August 1946 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917

August 1946 By MOTT D. BROWN, DONALD BROOKS -

Article

ArticleDean Robert G. Strong

August 1946 By JOHN HURD '21, -

Article

Article"Labor Has Come of Age and It Is Not Too Much to Expect It To Act Accordingly"

August 1946 By JOHN G. MACKECHNIE '31, -

Class Notes

Class Notes1919

August 1946 By J. KENNETH HUNTINGTON, MAX A. NORTON