His Death Deprives Dartmouth of A Beloved Leader

Now that Dean Robert C. Strong has gone, Main Street and the Administration Building recall most strongly his integrity. Some begin by saying informally, "He was a great guy" or "He did not have an enemy in the world" or "I can't believe it," but about Bob Strong people have so much to express that a single sentence and a shake of the head are not enough, and they go on to "Integrity—that's what he had," just as if they had at that moment discovered Bob's most effective characteristic and as if they wanted to emphasize how strongly it set him apart from other men.

Because of it, Dartmouth stands higher; because of it, Hanover is a better town. Another man might have served the College more flashily; he might have relied on inspired intuitions. Intuitions were not for Bob Strong; they would have been dishonest. For him integrity consisted of an inner compulsion which forced him to examine every shred of evidence and kept him awake until late at night. It forced him to do the meticulous work of being Director of Admissions and Dean of Freshmen in such ways as to get up at six o'clock in the morning and dictate twenty, fifty, even a hundred letters, to interview all day long students and parents after first carefully digesting necessary information, to remain at the Administration Building until other officers had gone, and to carry home papers for further consideration. Decisions came slowly, but time was of no consequence, and justice was.

Bob made nothing of such work; he might just mention it casually across the fence, as it were, to Virgil Poling, Director of the Student Workshop, who is building with his own hands the house next to the Strongs'. "He considered it as simply part of his duty," says Virgil. "It would not occur to him to boast or complain."

A director of admissions and a dean of freshmen faces more potential bitterness than perhaps any other college official; for a faculty, dominantly intellectual, is perpetually challenging the admissions system, and parents and alumni with blind enthusiasms resent objective appraisals of their champions.

Once a faculty group requested that Bob appear before them and answer their doubts concerning the quality of the Dartmouth undergraduate body, a result of the admission system administered by him, and the honesty with which he refused to gloss over weaknesses was so transparent that after two hours there were no more questions to ask. Even if not all the professors were convinced about the soundness of Dartmouth's Selective Process, all were about Bob's reliability and wisdom.

Personally and by letter he listened and wrote to parents and alumni and answered their questions and their querulousness point by point, and though some of them have been left unpersuaded, few were left disgruntled or embittered. Though refused, some candidates have felt so right about Bob's rejection of them that they have said, "He was mighty kind to me."

As Director of Admissions and Dean of Freshmen, Bob was occasionally subjected to telephonic high pressure about candidates from alumni who wanted special privileges because of what they had done in college and out, but Bob could say no. (Indeed, he could say it so well that he once referred to himself jokingly as The Director of No Admissions.) He could say no and add, "My responsibility to the College will not permit me to do this," which sometimes led to apology open or tacit at the other end of the wire.

Bob's multitudinous relations with principals of secondary schools, with alumni admissions committees, and with candidates were inherent in his office of Director of Admissions. Of equal importance but more time consuming were his efforts in the office of Dean of Freshmen. Every freshman at one time or another would go through it, and 700 seems like a large number when they must all be scrutinized. Many of them laid their problems before the Dean. Some were called in because of difficulties, scholastic or otherwise; others came in of their own free will because they were certain (the word travels fast enough in dormitories) of a fair hearing. When a freshman swims out over his head and when in deep water and in desperation begins to flounder, it takes more than a few minutes to get a hand under his chin and get the salt out of his eyes. The Dean of Freshmen has no time, but Bob Strong had all the time in the world if one of his students wanted, by telling the whole story, to settle Bob's or his own mind.

When the war came along, the College turned to the broad shoulders of Dean Strong for help in handling the V-12 Marine contingent, of which there were about 650 at the beginning. And he lugged that load too with a debonairness which belied his fatigue. One gains an inkling of how well he carried it when one learns that the Dean knew every Marine by his first name and acquainted himself with the minutest details of their private lives. An easier way would have been to sit back and let each Marine become a filed card perpetually taciturn.

So exacting is the two-man administrative job which Bob held down that one might expect a memoir to deal in terms only of it. Yet Hanover knew that Bob was as close to a universal man as exists in these parts.

Musician (on his first arrival in Hanover, a freshman, he tugged up the West Wheelock Street hill from the Norwich station, a suitcase in one hand and in the other a cello), he played well enough to be welcome in the Community Orchestra under Fred Longhurst.

As athlete, he liked skating and as late as 1940 on a faculty hockey team helped to defeat Ted Learnard and the alumni. He never did much slicking up on his golf game, but he had fun with Sid Hayward, John Piane, Jay and Archie Gile, Dave Storrs, arid an occasional visitor in the

''Norwich Open," when anything went. He skied with his wife and children on Oak Hill last winter, but by nature self deprecatory he told Dot that he was not a natural skier because he turned his toes out, which prevented him from stemming and got him eventually into an ever-extending split, impossible to maintain indefinitely at high speeds.

As amateur cook, he enjoyed doing things to lobsters and playing host over a grill and officiating with Max Norton on picnics. In his bachelor days, he liked to drink beer and to play poker with Jim McCallum, George Frost, Bill McCarter, Kip Orr '22, and others.

As gardener, even back in the first days of his marriage on Valley Road, he planted flowers and vegetables.

As singer and actor, he once played a leading role in a Gilbert and Sullvan Patience. He had a better-than-average collection of records of classical music. As orator, Bob was not naturally gifted, and he never liked to speak, but he worked at his delivery because it was part of his job. Eventually he developed so well that he was constantly in demand by school and alumni groups, though because he insisted on making extensive preparations with new facts, he could not always spare enough time to break away from his office work. As writer, he had to function mostly in his office with letters, but he never was content merely to rip off correspondence. Advised by Kip Orr during his early NewYorker days when Kip was earnestly trying to get established as a literary force, Bob in a more utilitarian way sought perfection of expression with the help of Fowler's Modern English Usage and Quiller Couch's book on the art of writing, with side excursions into the highly literate New York World and F. P. A.

And as a human being, Bob, despite the tremendous pressure under which he was put, loved to saunter down Main Street talking with students and workmen, with professors and shopkeepers, with returning alumni and carpenters at Trumbull's. Never a professional hearty man, he could let the situation fashion the shape of his banter; it was never forced. At the workshop Tom Dent might say with Scottish economy, "A fine thing," and Bob could work it in when circumstances were so bizarre that laughter bubbled over the chisels.

Dwarfing all avocations was his farming at Brookside, his home at the base of the Oak Hill ski tow, in which he engaged with the competent cooperation of his wife and his three children, Betsy aged 15, Johnny aged 13, and Tommy aged 7. Rugged, Johnny was his father's right hand man, who knows how to carpenter or butcher or hay. He is going away to camp this summer, the first time he has ever felt that he could take time off from his farming.

At first Bob and Dot set a Five Year Plan for themselves. Any less time was unthinkable with the house so dilapidated, piazza rotting, old tin cans under foot, weeds lush and rank—they needed all of it to clean up and paint themselves into some sort of decent order.

They got going, and before they could have possibly believed, they were possessors of many new things. They built a barn; Dot painted it. Lawns emerged green; animals munched in the stalls; hens squawked; a horse whinnied; sheep looked picturesque against Hanover hills.

For the Strongs, father and mother and daughter and two sons, farming was no mere romantic whim, here today, dissipated tomorrow. No hired men ever did the dirty work. They slaughtered the pigs. If there were desks or cabinets or tables to be built, Bob built them in his workshop A playroom and terraces with large flag, stones and a grill shoulder high for an amateur cook were matters of course Nearby woods furnished a pine tree for a flagpole, and a gilded ball on top above the American flag came from somewhere

Skis could be repaired as easily as a sign carved Princess over the horse's stall. Hanover winters are long, and birds like to eat, and so for the sunflower seeds was erected a bird-feeding station with, as an offset to aristocratic Latin inscriptions on John Stearns' wood carvings, the following stark injunction: COME AND GET IT.

The Strongs liked to eat also—they are sturdily built—liked the solid satisfactions of seeing their cold locker fill up with chicken and ham, beef and mutton, grown by themselves; their shelves bending under jars of canned vegetables and fruits, all arranged in orderly fashion. (Bob liked neatness. Tommy's ski clothes had to be just so. When Bob built a table for Madeleine Piane he borrowed an expensive antiquarian book from John to get the details squared away and waited until he could get just exactly the right wood from Trumbull's.) By this time the place was running to two or three steers, a few pigs, forty or fifty hens, three or four sheep, and three vegetable gardens, run in a cooperative fashion. That is, Bob would plant one row of vegetables for himself, one for Virgil Poling, and one for the Hitchcock Hospital. When Bob could not, Virgil did. Mr. Garipay down the road was in on it too. Everyone felt good.

Virgil Poling had in mind the whole creative process of the Strong family with its New England ingenuity when he remarked, "Bob was interested more in what materials did to a man than in what a man did to materials." But it could WOrk the other way round, for when A1 Dickerson wanted to raise chickens, Bob found time to go to Trumbull's with him and get some lumber and to the student workshop and get A1 started on a chicken feeder. A1 saw later that Bob really did the work, though he stood around and let Al think that he was making the feeder and doing pretty well at it. But really it works both ways: on the day of Bob's death, after Al had sent out the batch of telegrams (Tony Cacioppo, looking heavy eyed, crossed the street to ask if it were true, and he was not the only one) and after the rest of the first sad afternoon was over, he went home and tried to forget what had happened by working on his tomato plants, only to remember that it was Bob who had taught him everything he had known about how to grow them.

If Bob was creative when dealing with tools and enriching his family's life and his own, he was also creative in his college work. Having faith in human nature, he appealed to the best in people. Virgil Poling, who saw him every day over a period of years, never heard him say anything mean about a person, though Bob was never prissily Edgarguestish.

The spirit of a man like Bob Strong cannot be bottled up in a cubicle. It radiated beyond the offices of the Dean of Freshmen and Director of Admissions. President Hopkins valued his advice and sought it often, and Bob leaned on Mr. Hopkins. It was noticed too that Mr. Hopkins, opening his door to let Bob out, would still be chuckling at the unexpected turns in a Freshman dean's life. Bob's colleagues gladly talk about Bob's ability to face a tough situation. With a fundamental seriousness and excessive modesty, with dashes of bantering lightheadedness, he reached the right solution. After any meeting he liked to chat; even when most pressed, he never became crisply efficient. Though the papers under his arm would keep him up at night in his own study at home, Bob would talk on and leave a colleague wi-th the impression that the solution of the problems had been his own. Now that Bob is no longer here, a colleague realizes where the credit really belongs; but it would make no difference; living, Bob would have laughed off the thanks with a bit of persiflage, which was as much a part of him as his earnestness.

Bob's judiciousness and gayety are two of the reasons why his friends now say, 'Everyone liked Bob. He had a grand sense of humor. He was wonderful to be with." And then they must search for the right phrase to complete the picture. "He had absolute integrity."

ROBERT CHAMBERLAIN STRONG '24

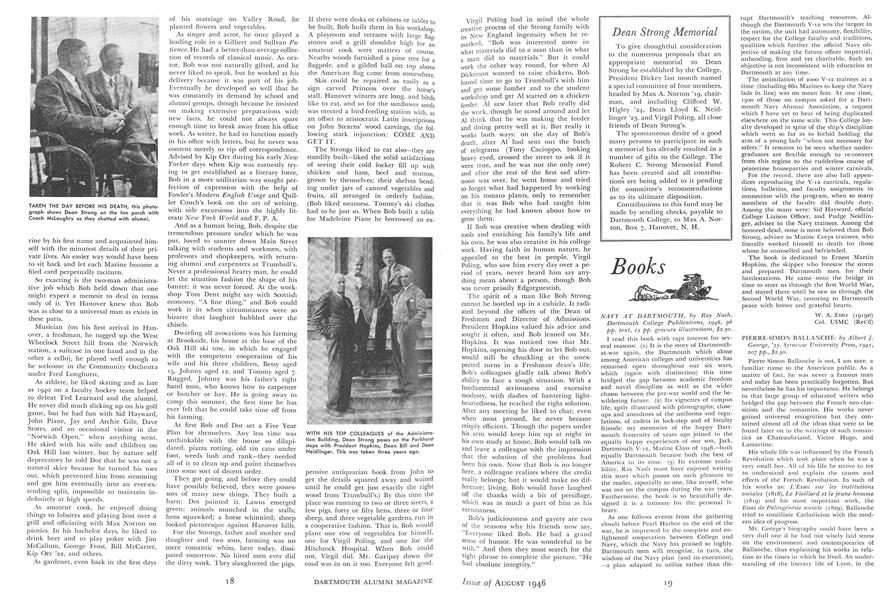

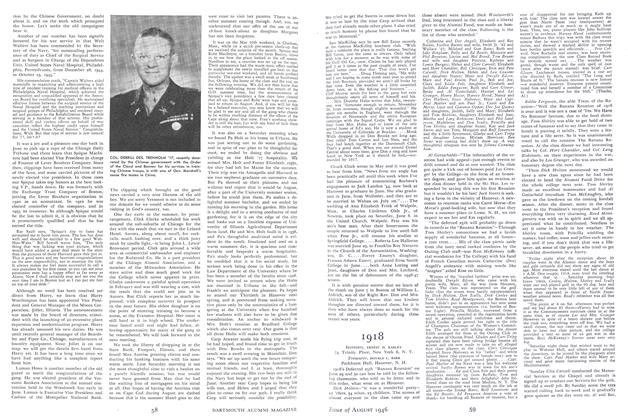

TAKEN THE DAY BEFORE HIS DEATH, this photograph shows Dean Strong on the Inn porch with Coach McLaughry as they chatted with alumni.

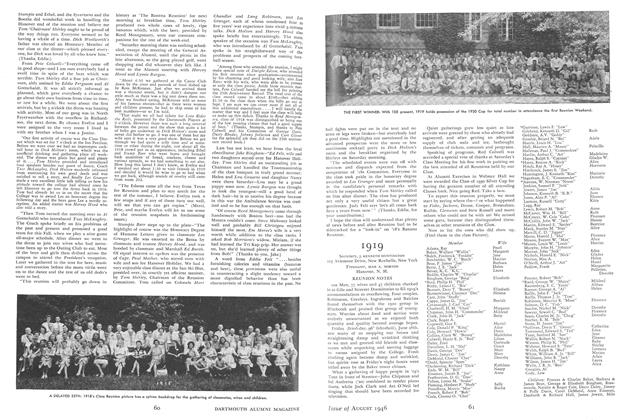

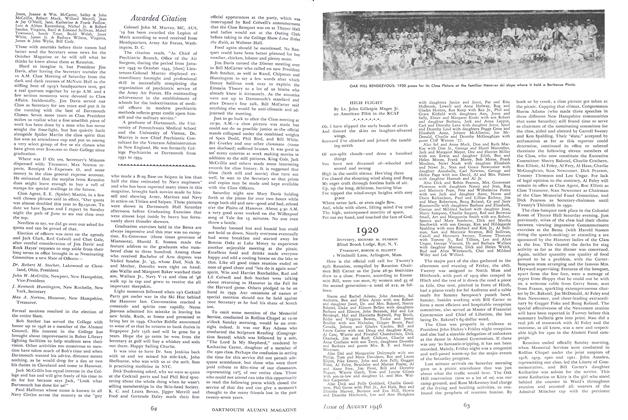

WITH HIS TOP COLLEAGUES of the Administration Building, Dean Strong poses on the Parkhurst steps with President Hopkins, Dean Bill and Dean Neidlinger. This was taken three years ago.

PROFESSOR OF ENGLISH

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1915

August 1946 By SIDNEY C. CRAWFORD, CHANDLER H. FOSTER -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

August 1946 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917

August 1946 By MOTT D. BROWN, DONALD BROOKS -

Article

Article"Labor Has Come of Age and It Is Not Too Much to Expect It To Act Accordingly"

August 1946 By JOHN G. MACKECHNIE '31, -

Class Notes

Class Notes1919

August 1946 By J. KENNETH HUNTINGTON, MAX A. NORTON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1933

August 1946 By GEORGE F. THERIAULT, LEE W. ECKELS

Article

-

Article

ArticlePRESIDENT HOPKINS GIVES UP ALUMNI TOUR FOR TRIP SOUTH

February 1921 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Poems

October 1959 -

Article

ArticleHe Went to Dartmouth and Became a Diplomat

MAY • 1988 -

Article

ArticleClass of 1992

Nov/Dec 2005 By Bonnie Barber -

Article

ArticleMemorandum

November 1940 By Ernest M. Hopkins -

Article

ArticleTHE DRESDEN PRESS*

May 1920 By Harold Goddard Rugg