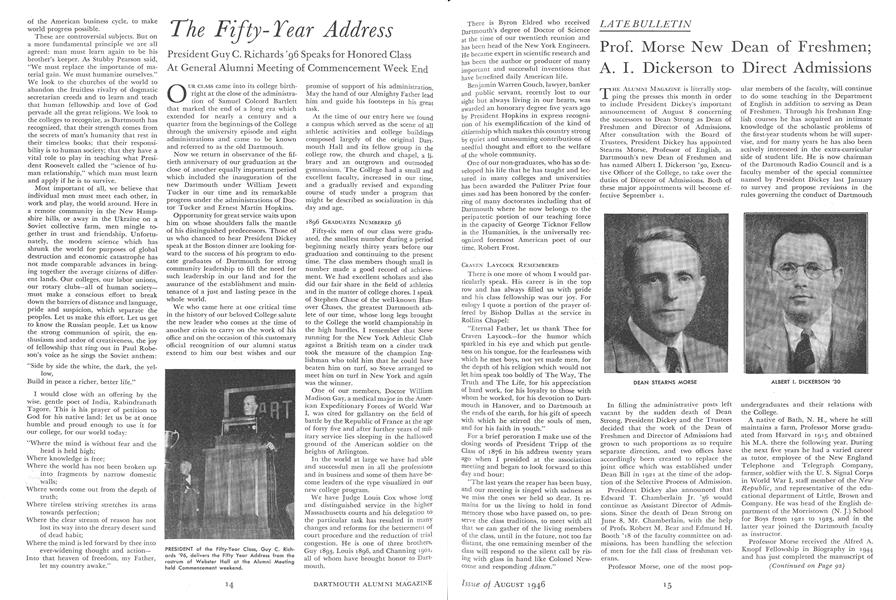

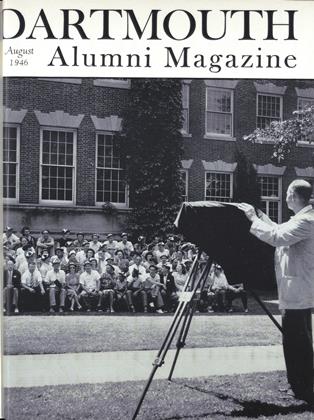

Richard Morse '44, Speaking for the Graduating Class, Reaffirms Faith in Human Spirit Despite Evils of the Day

PARENTS, FRIENDS, AND TEACHERS: In years of worldwide war we came to Dartmouth and found a gentle, temporary refuge from the horrors of our time. Some of us in the Navy and those of of us in medical or engineering courses overcame youth's natural impulse to get in the fight, but most of us who graduate today drifted away, one by one, into the War. We dropped our bombs on Hamburg, threw flames at the Japs on Okinawa, patrolled the vast grey oceans in our stealthy submarines. The boredom of the long grind, the ugly painful slaughter of war treacherously threatened to harden our hearts; but we were lucky and came back to Hanover, to cherish again its lovely peacefulness, its friendly smiles; to hear again its music softly filling the campus in the long Spring nights.

How have we reconciled the evils of our day with its beauties? How has our confusion been resolved? Has our idealism succumbed to the realism of the battlefield, have our bright dreams turned into the cold despair of hate and cynicism? These are the questions you might ask us, and you have the right to ask. Today, in this moment of ceremony, let us answer you from our hearts. Let us shed the tough exterior of a generation of soldiers, and abandon our native reticence. Let us give you reassurance.

Today we reaffirm to you our faith in the human spirit. In the remote places of the earth we have seen man's dignity, the steadfastness of his integrity. We entered a village in far-off Burma and found the patient bravery of the human heart in a loving Burmese lady, whose aged mother had just been killed by American planes, whose son was a prisoner of the Japanese, perhaps already dead. Her courage and her sacrifice were matched in gallantry by our own companions—by Stubby Pearson who stood here four short years ago, saying, "Man is man and that is all that is important," and then dove his plane into the Pacific in a final salute to his deep hope for the future. The pot-bellied children of Calcutta and Kunming taught us the pathos of man's hunger; we heard his wistful, hopeful laughter in children crowding around our jeeps in France and Italy. Man's creative spirit blossomed for us in a tiny but neat flower bed amidst the ruins °f a London suburb; the beauty and truth of the human soul sang out to us in a quiet church hymn sung by a girl in Australia or here in Hanover. We knew companionship with strangers as we found in them this fight of human goodness, and enjoyed the confidence of a firm handshake as we met old friends again. The world's people have been good to us.

At Dartmouth we found man's spirit in ancient books, brought to us by helpful teachers. We studied man's endless struggles to gain political and economic freedom. We read the inmost sentiments of his heart and mind recorded in his poetry, his philosophies, his religions. In ancient Indian and China, we have learned, devout religious teachers knew God's presence in every human soul, regardless of race, caste or color. It was centuries later that Christ enjoined man to "love one another as I have loved you." This eternal message of the great religions, this assertion of the brotherhood of man, is also the strength of our democracy, our world society. In it lies the future.

But you will say this optimistic picture is an unreal dream. You will accuse us of forgetting the aggressive, lustful nature of man at war, the sadistic perversion of man's torture chambers in Nazi Germany. You will remind us of sordid incidents of graft and looting, of racial hate and national conceit of which Americans have been as guilty as any. You will point with dread to the United States testing atomic bombs, or perfecting bacteriological weapons, and to Russia loudly boasting of her strong Red Army: all this in a world stalked by famine, crippled by profiteers, by strikes and disagreements. Fear and suspicion. rales men's hearts. The world grows dubious about its future.

We who are graduating can not presume to try to answer these problems today. But we grew up in great, serious times, and many of us have taken responsible parts in great, awful deeds. We believe, as TheDartmouth said, that it is every man's duty to try to understand his world. We feel our experiences give us the right to be heard when we have deep convictions on the principles that should guide our nation's actions.

We admit the truth that there is a beast lurking in the heart of man; callous disregard of the moral law, indifference to suffering have multiplied in these terrible years. But we have studied how man has instituted governments and law to repress this evil side of his nature. In our democracy we, the people, are the source of this law; our history consists of our efforts to uphold it, to amend its scope to meet the needs of the times. Today we feel that human society needs world law, world government, at least with power to quell the brutal aggressions and abolish the suicidal weapons of modern science. The Nuremburg trials, the Lilienthal and Baruch reports have been hopeful steps. Now we hope to see our statesmen move positively to encourage both Russia and the United States to surrender the outdated, exaggerated privileges of national sovereignty to a world authority. The confidence and trust between us and Russia, which have so badly degenerated during the past year, must be rebuilt. We know this is a desperately difficult assignment. Many of us think it can be done if the United States will abandon the unilateral actions that invalidate the sincerity of our stated purpose, and if our nation will take the lead in renouncing the futile, blustering methods of power politics.

But there is another, equally important task that challenges us today. The great productive resources of this earth, of which the greatest is man's skill, must be channeled into a fuller distribution among the impoverished of the world. If we are proud that we are the foremost industrial nation today, we must be humble and generous also, for ours is thus the heaviest responsibility. International conferences have produced encouraging economic agreements; the United Nations Economic and Social Council offers grand hopes. But in the back of everyone's mind throughout the world is the paralyzing spectre of another major United States depression, which, like a chain-reaction, would spread chaos and tyranny around the world. We must prepare now to prevent this calamity. Sometime ago, Mr. Stassen called on government to secure the cooperation of all economic groups—labor, management, farmers, consumers, and export economists —in developing a basic economic policy. Many of us believe that far-sighted, democratic planning of this cooperative nature is vital to limit the ravages and extremes of the American business cycle, to make world progress possible.

These are controversial subjects. But on a more fundamental principle we are all agreed: man must learn again to be his brother's keeper. As Stubby Pearson said, "We must replace the importance of material gain. We must humanize ourselves." We look to the churches of the world to abandon the fruitless rivalry of dogmatic secretarian creeds and to learn and teach that human fellowship and love of God pervade all the great religions. We look to the colleges to recognize, as Dartmouth has recognized, that their strength comes from the secrets of man's humanity that rest in their timeless books; that their responsibility is to human society; that they have a vital role to play in teaching what President Roosevelt called the "science of human relationship," which man must learn and apply if he is to survive.

Most important of all, we believe that individual men must meet each other, in work and play, the world around. Here in a remote community in the New Hampshire hills, or away in the Ukraine on a Soviet collective farm, men mingle together in trust and friendship. Unfortunately, the modern science which has shrunk the world for purposes of global destruction and economic catastrophe has not made comparable advances in bringing together the average citizens of different lands. Our colleges, our labor unions, our rotary clubs—all of human societymust make a conscious effort to break down the barriers of distance and language, pride and suspicion, which separate the peoples. Let us make this effort. Let us get to know the Russian people. Let us know the strong communion of spirit, the enthusiasm and ardor of creativeness, the joy of fellowship that ring out in Paul Robeson's voice as he sings the Soviet anthem:

"Side by side the white, the dark, the yellow, Build in peace a richer, better life." I would close with an offering by the wise, gentle poet of India, Rabindranath Tagore. This is his prayer of petition to God for his native land: let us be at once humble and proud enough to use it for our college, for our world today: "Where the mind is without fear and the head is held high; Where knowledge is free; Where the world has not been broken up into fragments by narrow domestic walls; Where words come out from the depth of truth; Where tireless striving stretches its arms towards perfection; Where the clear stream of reason has not lost its way into the dreary desert sand of dead habit; Where the mind is led forward by thee into ever-widening thought and actionInto that heaven of freedom, my Father, let my country awake."

RICHARD MORSE '44, son of Prof, and Mrs. Stearns Morse of Hanover, delivered the Valedictory to the College on behalf of the graduating class at this year's Commencement Exercises.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1915

August 1946 By SIDNEY C. CRAWFORD, CHANDLER H. FOSTER -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

August 1946 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917

August 1946 By MOTT D. BROWN, DONALD BROOKS -

Article

ArticleDean Robert G. Strong

August 1946 By JOHN HURD '21, -

Article

Article"Labor Has Come of Age and It Is Not Too Much to Expect It To Act Accordingly"

August 1946 By JOHN G. MACKECHNIE '31, -

Class Notes

Class Notes1919

August 1946 By J. KENNETH HUNTINGTON, MAX A. NORTON