The Scriptural Injunction Applies Today to College Admissions, Which Are Here Discussed by the One Person Who Can Give Dartmouth Men the Authoritative Answers to Their Questions

You and your boy should understand," the admissions officer was saying, "the competitive situation which a boy faces for college admission today. Take, for example, our 6000 applications for 650 places this year. The competition is pretty keen. On the other hand, we must not let it appear so fantastically difficult to get into college that even good men will not try. I know of no college which is in imminent danger of enrolling a freshman class composed exclusively of supermen."

"Well," said the father, taking a long look into the eyes of his son, "seventeen is no age at which to start running away from competition."

The boy nodded, a little shyly, more than a little eagerly.

This is not a parable. It is a fragment of conversation which actually took place day before yesterday, which has had hundreds and hundreds of counterparts in recent months.

Fact or parable, it could serve in itself as a fair summary of the problem of college admission today, or it could serve as the text of a really exhaustive, definitive exposition of the numerous facets of college admission problems.

This present piece will not stop with the text. Neither can it, within the space which the editor can devote to it and within the fifteen or twenty minutes which readers might be willing to spend on it, undertake the definitive treatment.

Consider even a fragmentary listing of the facets which an exhaustive exposition of admission might include.

It might include consideration of Dartmouth's relationships with the College Entrance Examination Board system, past and potential. This would be a major treatise in itself. It might include a diatribe on the "first choice" shibboleth which some colleges in our group apply, and which the College Entrance Examination Board aids and abets in the face of a rising resentment among the schools and their students—a resentment against its unfairness in these times when a boy just can't choose" his college. A definitive document might include treatment of the unparalleled participation of Dartmouth alumni in recruiting and evaluating candidates for admission, but that also would require a long, long chapter. There might be consideration of preparation for Dartmouth, with some discussion of public versus private schools; and as the converse of the competition for admission, there might be examination of the competition among the colleges for the best men in the schools, which would get us into the whole realm of college public relations.

And so on. But before I become like the anesthetic orator who exhausts his hearers with a forty-minute summary of things he is not going to talk about, I proceed with the immediate subject of this piece, which is: (1) the setting of college admissions today; (2) the principles of Dartmouth's Selective Process; (3) a sketchy outline of its procedures; and (4) a consideration of the status of sons of Dartmouth men applying for admission.

THE SETTING "Enter ye in by the narrow gate .... and few be they that find it," say the Scriptures.

The portals of the colleges and universities today are indeed narrow in proportion to the number seeking entrance. The absolute good required to pass through the straitened way of Matthew's gospel is a little different from the virtue required for those who seek to wind over the ever broader and smoother roads provided by the New Hampshire Highway Commission. These latter travellers meet only relative—i.e., competitive—standards. But the competition is rugged enough.

We cannot complain, because Dartmouth introduced the now prevalent competitive elements into college admissions. Having made this bed, we must lie in it with all possible grace, however fitfully admissions officers may sleep in it.

An eminent headmaster was reflecting the other day on the competitive nature of college admissions and the difficulty of educating the public to this fact. "Up to 25 years ago," he recalled, "all you had to do was pick your college, 'pass' the College Boards with the equivalent of the grade of C, and you were in. Then you people at Dartmouth introduced your selective process as a more adequate basis for selecting students from the enormously increasing number of applicants. Now all the colleges are doing just about the same thing. But people don't realize what a competitive business it is, and it's going to take years to educate them."

Although we may claim, with currently restrained enthusiasm, to have "invented" the competitive system of selection, we can certainly claim no monopoly on it now. Colleges which before the war were paying agents in the field five or ten dollars a head for freshmen are now looking down their lengthening noses with some hauteur at candidates who hesitate to swear on a mountain of Bibles that Blank College has been their dearest aim since birth. Historic liberal arts colleges such as Princeton, Harvard, Amherst, Williams and Yale are in the same boat with us. Such published statistics on applications in relation to openings as I have seen quote Dartmouth with the highest ratio, but these are necessarily loose statistics, and all these colleges are undoubtedly in very similar positions.

Statements have been pouring from the various college campuses, seeking public understanding of the problem and, more particularly, the understanding of the respective alumni bodies. Alumni can help: by educating other, less well-informed, alumni; by reinforcing the college's public relations which are inevitably strained when only one out of eight or ten applicants is destined to be admitted.

The factors contributing to this enormous bulge of applications are under discussion daily in newspapers and popular magazines and do not need to be reviewed here.

How long will these conditions last? Indefinitely, so far as we can see. Some prognostications say that the crisis will not be reached until 1950, but these relate mainly to enrollments rather than admissions. For colleges like Dartmouth which intend to return to their pre-war enrollments, and to do this by admitting only normal-sized freshman classes, it seems unlikely that the pressure of applications in relation to openings will change materially.

Continued national prosperity (whatever that means, if anything, in these inflated days) and students seeking to escape the congestion of the state universities, which have made such heroic efforts to meet the prodigious obligations thrust upon them, would tend to increase the number of applications to the private colleges where, in varying degrees, expansion has been more controlled. On the other hand, the backlog of veterans has been largely liquidated with the '51 applicants. This group (very largely young veterans with no war experience, treated exactly as all other candidates) included many men who prior to eligibility for G. 1. educational benefits, had had no hope or intention of entering college, and were hopelessly unprepared. As a result, whereas about 25% of our '51 applicants were veterans, only about half of this proportion were able to qualify. If a dropping off of applications from this hopelessly unprepared group is to be expected, as I rather believe it is with increasing public understanding of the situation, it will come from the bottom of the list, rather than from the top where the competition exists. So it does not seem likely that the competitive situation will change much in the next few years.

A severe depression or the enactment of a universal military service law might alter the situation, but speculating on these subjects is pure crystal-gazing. The depression of the '30's did not materially affect Dartmouth applications.

I find myself referring to the present fierce competition as "bad" or "worse," because this has become conventional and it comes naturally to an admissions officer struggling to stay 011 top of his job. Obviously, however, those colleges are most fortunate which have the largest number of applicants to choose from. (Or so we keep reminding ourselves.)

Anyway, for better or for worse, the situation seems unlikely to change much.

PRINCIPLES OF THE SELECTIVE PROCESS

"Has the Dartmouth admissions system changed?" we are often asked. It has not changed. But the conditions

under which it operates have changed enormously, as indicated in the paragraphs above.

The system is very simple, and very flexible. As defined in the minutes of the Board of Trustees, it reads: All candidates whoare admitted to Dartmouth College shallhave satisfied the requirements of the Selective Process for admission and shall havepresented evidence satisfactory to theCommittee on Admissions that they arecompetent to carry on their course of studyat Dartmouth College.

This simplification, enacted in 1933 after clue discussion and endorsement by the faculty, abolished the traditional 15- unit requirement. This was not designed to make it "easier" to get into Dartmouth. It was promulgated at a time when the competition for admission, and the resulting standards, were on a consistent upward curve. Indeed, it recognized the fact that under these rising competitive criteria. the old 15-unit minimum requirements were no longer necessary or useful as a "floor." Also, the increased flexibility made it possible to admit an occasional boy of rare promise who might, for one reason or another, be technically deficient according to the 15-unit provisions.

Year by year there has appeared in the official bulletins of the College—without change, so far as I know, during the 25 years in which the Selective Process has been in operation—an interpretation of its principles. As appearing on Page 41 of Dartmouth College Bulletin Number 4, Regulations and Courses, November, 1946, it reads:

Dartmouth holds unreservedly that definite evidence of intellectual capacity is indispensable, but it believes that, after such evidence is established, positive qualities of character and personality, range of interests, and capable performance in outside activities should operate as determining factors in selection. All candidates, therefore, are judged on the basis of the following qualifications:

SCHOLARSHIP

The record of each candidate for his entire secondary school course is carefully studied with particular emphasis given to the work of the last two years. If a candidate is to be admitted, his scholastic record and the recommendation given to him by his school principal must show that he is possessed of an educational background sufficiently rich and broad in range to indicate definite intellectual capacity and ability to do justice to the academic work of the college. A candidate may present for admission any subjects taught in an approved secondary school which represent accepted courses in the following fields of study: English, Foreign Language (ancient or modern or both), Mathematics, Natural Sciences, Social Studies.

CHARACTER AND PERSONALITY

Character is used to denote such qualities as trustworthiness, initiative, dependability and conscientiousness. The characteristics which are included under the term "person alitv" are those which lead naturally to some breadth of contact and to some variety of interest. It is understood that the term necessarily deals with intangibles rather than with absolutes. In general, however, it may be said that the man whom the college desires to enroll in its undergraduate membership is the man of intellectual competence and stalwartness of character, if, in addition to these attributes, he possesses likewise the qualities which collectively attract rather than repel the friendship and confidence of others, thus enabling him without sacrificing individuality to cultivate respect and to establish influence among other men.

GROUPS TO WHICH PREFERENCE IS GIVEN

Properly qualified sons of alumni and officers of Dartmouth College, residents of New Hampshire, residents of states west of the Mississippi or south of the Potomac and Ohio Rivers, and residents of territories and dependencies of the United States and of foreign countries, are given some preference at the time of selection. These four groups constitute approximatelv twenty-five per cent of the entering class.

I don't know whether President Hopkins or Dean Bill, the first director of admissions, originally authored this statement, or whether they both contributed to it. But I must record, after a year's rather intensive experience working under this interpretation of the principles of the Selective Process, my respect for its aptness and its adequacy.

As I began to operate in the admissions field, questions arose in my mind at various points concerning the possible desirability of reviewing and perhaps revising some of our procedures. Some of these questions are now under study, and will be considered by the Faculty Committee on Admissions, and discussed with the Alumni Council's Committee on Admissions and Schools. But the more I have worked with our Selective Process, the more respect I have developed for its essential soundness, and the more uncertainty I have whether any significant changes are immediately in order.

For my own guidance, I have tried to supplement the primary interpretation of the Selective Process, as quoted above, with an interpretation of the immediate objectives of the process in terms of Dartmouth's aims and purposes as defined by the President. Basing it on the College's "primary obligation to human society"—a statement by President Hopkins echoing Dr. Tucker's emphasis of "public-mindedness" and strongly restated by President Dickey—there appear to be five points at which the Selective Process should seek to operate toward the fulfillment of this obligation.

(1) Since the possession of a mind is what distinguishes human society from the other primates, the possession of a mind becomes our first criterion, so that Dartmouth may send forth men with goodand well-trained and well-informedminds, and with high purposes.

(2) President Dickey has emphasized, and re-emphasized, the urgency of the time element at the critical point which human society now faces. As he has said: "There is so little time." Thus it is the obligation of those of us working on admissions to seek with more eagerness than ever to makeevery man count: to seek men who will, in addition to having well-developed mental equipment, have also the drive, the determination, the vigor, the qualities of leadership to make their influence effective.

(3) Assuming that Dartmouth's influences are good, it should be our objective to spread them widely. Men tend to return to their original home communities. Thus we find that the emphasis on geographical distribution becomes, if anything, more significant than ever.

(4) Then there is the diversification of the student body, which is vital to that mutual education which goes on in a college like Dartmouth. You will recall that favorite quotation of President Hopkins about the "impact of youthful mind on youthful mind" as one of the most important parts of the educational process. This is where diversification comes in, so that this mutual impact may be most comprehensive, as men of widely differing backgrounds react upon one another. This diversification should include the geographical distribution mentioned above as well as the broadest possible range of economic, social, religious and occupational backgrounds, so that Dartmouth may continuingly and increasingly represent the whole rich diversity of American life.

This is as good a point as any at which to underline one aspect of this diversification—the range in economic backgrounds. It is profoundly important that Dartmouth should continue to attract the boy of limited means. It is perhaps permissible, in a family organ of this sort, to recognize the fact that this aspect of Dartmouth's constituency is much envied by some of our sister institutions which are much concerned by the great and growing degree to they draw upon the sons of the upper middle class, as represented, for example, by the high proportion of their men entering from the private schools. The strong pull that Dartmouth has on the best men in the public schools is one of our great assets. And it is going to take watchfulness and real effort to maintain this strength. President Dickey had this very much in mind in his exceedingly careful attention to the public relations aspects of the recent increase in our combined fee, and the strong emphasis put upon the fact that it should not and would not become more difficult for the man of limited means to get a Dartmouth education. But this public relations problem is not one that disappeared at the time of the announcement of the change in the fee: it is a continuing job in which all alumni must actively participate. A fee of $550 looks like quite a lot of money, and it is important to Dartmouth that the promising but impecunious high school graduate in South Dakota should realize that men with minimum financial resources have always been able to get a Dartmouth education, and are still able to do so.

And still further underlining may be appropriate for one particular segment in the group of men of limited means—the marginal man. This is the candidate whose parents, with sacrifices, have always been able to pay for the things they have provided for their children and who might consider it compromising to their self-respect to ask for financial aid. This is a group which, because it is hard to identify, is deserving of our particular attention. It is well for these men to realize that even the student who pays the full fees at Dartmouth is paying only half of the cost of his education.

(5) And now, after diversification of the student body, we come to breadth of interest in the individual man.

This is, if I may startle you with an original observation, a complex world. It is not going to be understood, let alone be influenced, by the one-track person. The really brilliant man, ear-marked as a potential intellect of the first rank can be indulged in some one-sidedness—although, it is to be observed, he seldom is one-sided. But the man of mediocre intelligence who is the professional mark-getter and who comes up to the Selective Process with a high standing in his class but with nothing else to offer, does not—according to Dartmouth admissions concepts which I am not disposed to controvert—offer as much promise of contribution either as an undergraduate or ultimately as a citizen as the man whose intellectual equipment may be assumed to be approximately equal but who, having channeled his energies over a somewhat broader area, may present somewhat fewer A's.

When I undertook this work, I had a sub-conscious fear, which I did not recognize at the time, that a Selective Process which aimed for the "all-round man" was in grave danger of ending up with the mediocre. It was only after that fear had been substantially relieved by experience that I realized I had had it. Discerning school-men helped me over this hurdle, particularly in their evaluation of "markgetters." Time after time we would find them saying, as one widely respected educator put it: "This boy would be a more liberally educated person if he were less self-centered and less concerned about his grades."

So when it is asked whether Dartmouth is now interested only in grades, the answer can be given with conviction that this is no more true than it ever was.

There is a reverse side to this coin. There is apparently a segment of the population which thinks that Dartmouth is a haven for lame ducks. A disappointed mother said to me last spring, more in sorrow than in anger: "I thought Dartmouth, of all places, would understand Tommy's low marks." A New Jersey man came in with his two sons. The older one's academic credentials were very dubious and I was unable to be very encouraging. After that situation had'been covered, I turned to the younger lad with the doubtless fatuous conversational gambit: "Well, I suppose I'll be hearing from you one of these days." The father quickly interrupted: "No, Dickie gets very good grades and he thinks he wants to go to ," and with a charming blush promptly bit off his tongue.

Actually, of course, Dartmouth is not, compared to its sister institutions, either an asylum for lame-brains, a Mecca for "greasy grinds," or a closed congregation of cerebral Colossi. It is true, of course, that some of the men whom we admit have been, or will be, turned down by our sister institutions, while every year some of those to whom we have said "no" turn up on these same campuses. This sort of thing can happen by the "rub of the green." But, in spite of ostensible differences in admissions systems, the type of candidates sought and the competitive situation which they face, are undoubtedly very similar in this group of colleges and universities.

A word of warning is perhaps in order to the "mark-getter's" antithesis, the "activity boy," who rushes around involving himself in a multitude of clubs, organizations, and activities without achieving real distinction in any of them or in scholarship either. These assiduous dilletantes and busybodies must be assessed a notch below the professional "mark-getter," who at least knows enough to put first things first and avoid spreading himself too thin.

We sometimes find a candidate apologizing for the fact that he is not a varsity athlete. This is ridiculous. Sometimes we find alumni sponsors professing to apologize for the fact that their proteges are accomplished in sports. This is equally silly, or insincere, or both. Men who have real distinction in athletics and sportsmanship have a valuable contribution to make to undergraduate life. So do men who have real distinction in music, dramatics, debating, journalism, and in other special skills and pursuits, and whose qualities of leadership have won notable recognition from their contemporaries. And if they are outstanding in any of these qualifications, it is important that we know it, as it is often difficult to distinguish the merely average or superior from the superlative.

After all this has been said, it must be reemphasized that scholarship remains the primary qualification. It would be gratuitous to remind an alumni audience that Dartmouth is an educational institution, not a boys' finishing school or an athletic association. It would be insulting to the ALUMNI MAGAZINE'S readers to belabor this point, but since an occasional correspondent enjoins us "not to forget the average boy," the point perhaps should not be ignored altogether.

It is well known that all the professional schools screen their men primarily on scholarship, whether for law, medicine, engineering, or teaching. And there is every tendency for business to do the same. The libraries are full of reference material on this point. The piece which I happen to have at hand, recently recalled to my attention by a friend, is an article appearing in Harper's Magazine some years ago entitled "Does Business Want Scholars?" by Walter S. Gifford. This article is largely based on a study of the Bell System by Dartmouth's eminent E. K. Hall '92.

The answer that Mr. Gifford gives to his own question is of course an emphatic "yes." He quotes an earlier study by President Foster of Reed College with a similar interrogatory title "Should Students Study?", in which the conclusion is reached: "Indeed it is likely that the first quarter in scholarship of any school or college class will give to the world as many distinguished men as the other three-quarters."

Mr. Gifford—after carefully recognizing that salary and success are not necessarily synonymous, but assuming that in business they largely parallel each other, and granting that there are occasional notable exceptions—shows that in the Bell System men from the middle third of their college classes do better salary-wise than men from the last third, that the difference is still greater between men from the first third and men from the middle third, and that a still greater differential exists between those from the first tenth and the rest of the first third, and that the differentials between these four groups increase withevery passing year.

Each of us can point out, as some have pointed out to me, individuals who barely squeaked through college, or flunked out of college, or didn't go to college at all, but who have had the most distinguished of careers. These are men who did not get their superior intelligences organized or motivated until later. But surely no one will argue that they achieved their successes because of, rather than in spite of, their deficiencies in scholarship.

The writer of this piece and most of its readers are average men. Most of us can find in our lives sufficient sources of satisfaction and self-respect. But we do not derive these satisfactions from our averageness. Those mornings when we feel especially good we do not walk down the street throwing out our chests and saying, "Gee, it's wonderful to be mediocre!" No more can we propose that a college admissions office should set out in purposeful pursuit of mediocrity. The averages will take care of themselves.

Perhaps President Dickey had some of these factors in mind in his magnificent talk to the Alumni Council last June, when he spoke of the danger that alumni bodies might seek to "cast their colleges in their own molds." He was not speaking particularly of Dartmouth in this connection, but we Dartmouth men, who play a uniquely active and vital and influential part in the life of our college, cannot ignore the injunction.

There is one type of average boy who is all but irresistible. We have all seen these and few of us have been able to resist their appeal: the boys with exceptionally engaging personalities and boundless Dartmouth enthusiasm whom, for convenience, I shall call—with genuine friendliness and no contempt—"personality boys." I remember one such who was sent to me by a friend a year or so ago. I went overboard for him and sent my testimonial to the admissions office, to join with all the others, concerning "the most engaging average boy I ever saw." He was admitted and, out of curiosity, I looked into his record the other day. It was bulging with obviously genuine evidences of strong Dartmouth ambitions since infancy. But unhappily, he was then on the brink of flunking out, and it was evident that if he should survive by the skin of his teeth, it would be with a minimum contribution to Dartmouth's intellectual or community life. Personality and Dartmouth enthusiasm are just not enough.

After considering (1) the mind, (a) drive, vigor, determination etc., (3) geographical distribution, and (4) general diversification, we have invaded a number of byways in discussing (5) diversity of interest in the individual man. Finished, at last, with interpretation of the principles of the Selective Process, we can sketch out its procedures before turning to alumni sons.

PROCEDURES OF SELECTION

Application for admission to Dartmouth may be made for a candidate anytime between the "It's a boy!" flash and March 1 of the boy's last year in secondary schooland preferably at least a few months before the latter deadline. All that is required is a small preliminary application card—no fee.

In the fall of the senior secondary-school year, we ask all those so registered with us if they are still interested. To those who say "yes" we send, during the late fall, three application forms and instructions. Form 1, to be filled out by the candidate, asks for full personal and biographical details. Form a asks the candidate to pen, without help, a handwritten letter to the director of admissions, telling about his special interests, the factors that have contributed to his development, and his expectations of college in general and Dartmouth in particular.

Form 3 is the "Personal Rating By Alumnus," which is to be handed by the candidate to someone who knows him well and who will complete the form and send it directly to us. An alumnus is suggested because he knows both the College and the candidate. But if the candidate has not been well acquainted for some time with a Dartmouth man, he should give the form to someone who does know him well. This person is expected to be prejudiced in favor of the candidate, but he will not serve the candidate well by writing him up as a Messiah when the rest of his papers will indicate that he is substantially less than that.

Before the Christmas holidays, we start channelling the Form 6's through the Alumni Councilors to the alumni interviewing committees across the country. We like to have the candidate interviewed, if possible, in his home community. These committees, although they will ask the applicant about his scholastic standing to make an over-all estimate of his promise, report chiefly on his personal qualities. These reports, more than anything else except possibly the candidate's letter, round out the picture of him as a human being and bring alive his folder-full of papers.

In late February, after the first half-year is completed in the schools, we start sending Forms 4 & 5 to the school principals. On Form 4, the principal evaluates the applicant's seriousness of purpose, industry, initiative, influence, concern for others, emotional stability, etc., and writes an informal supplementary paragraph describing what kind of person and student the applicant is. On Form 5, he gives the applicant's complete school record in detail, his standing in class, his strong and weak subjects, the results of tests he has taken, and an opinion with regards to the applicant's comparative promise as a prospect for admission to Dartmouth. These are the key documents in the Selective Process, based as it is on what the candidate has demonstrated that he not only can but will do. The school men are extraordinarily painstaking, discriminating and honest in their evaluations; and they realize, of course, that their schools are rated by us on the degree to which their graduates live up to these predictions.

Only rarely do we find a school man trying to sell us one of his fourth-rate seniors, and from these infrequent instances we get some of the all-too-few laughs that there are in this business. These write-ups, without too much exaggeration, run something like this:

"Dear Sir: "I can give Blob Doolittle my warmest recommendation for admission to Dartmouth. It is true that he is in the lower ranges of the fourth quartile (259 in 260), but as you know, Hilltop Academy's selection is so careful, and our standards of grading and promotion so severe, that there is actually no such thing as a second, third, or fourth quarter at Hilltop. Actually, Blob only began to show his true intellectual power at the grading period week before last, when he almost got up to the college certifying level in two of his four courses. Our passing mark is 50, and we set our college certifying level at 35. Our honors mark is 38, high honors at 40, and highest honors at 41 1/2. Ordinarily, fewer than 99% of a class achieves highest honors, but in this year's extraordinarily able senior class all members came through with flying colors. Blob, although a little shy in his marks, qualified by winning some extra points through his loyal service as Assistant Captain of the Mimeograph Squad. He has had some difficulty meeting Hilltop standards in English, mathematics, history and the foreign languages, but he is now beginning to show real strength in all of them and will certainly do at least average work at Dartmouth. Personally, Blob Doolittle is a boy of charming personality, cultured family, and fine character and integrity.

"In fairness to Blob, perhaps I should put in proper perspective that adolescent escapade of his sophomore year in which he attacked his house mother with a hand grenade, tommygun, and machete. Mrs. Carmichael was such a beloved character on the campus before her unfortunate demise that we could hardly over look the incident, and we had to suspend him for 48 hours. He won the heart of every member of the Disciplinary Committee by the way he took his punishment like a man. Things took a somewhat more serious turn last week when Blob was unfortunately discovered smoking corn-silks behind the gymnasium by the janitor's blind mother-in-law, after hours. For this grave infraction of discipline, we are having to withhold his diploma, and I hope it will not prejudice his chances at Dartmouth. I think the Trustees may grant him the coveted Hilltop sheepskin at a special meeting next week.

"Blob has real athletic promise, having been alternate on his house volley-ball team during the summer term of 1943 (when he was taking his French and algebra for the third time.) Any college which enrolls this fine young man will be fortunate. He would add tone to any group."

As a candidate's several forms come in they are separately read, evaluated, appropriately underlined and annotated, and rated. These ratings, along with a good deal of summarized information, are put on a master card for every candidate which, when completed, gives a quite comprehensive picture of the candidate.

In late March, when the bulk of the applications are complete, they are piled (master-cards attached) mountainously around a barricaded room. Each folder is then read as a whole. Those clearly superior are marked tentatively for admission. Those obviously inferior are marked for non-acceptance. When, after a couple of morning-to-midnight weeks of work, this process is completed, there remains a substantial group of applications which have been set aside. These are then examined again, with particular attention to such things as weak spots in English, mathematics, or the foreign languages, and repeated courses in which grades have to be discounted. By this time, the critical competitive level for the class has been determined and, measuring the individual applications against this yardstick, the final selections are made.

I was, I confess, a little surprised and no little relieved to find that this critical level is determinable with fair precision, as I had feared that there might be elements of whim or lottery in the final stages of narrowing down the marginal group. It was a comfort after it was all over to feel, without assuming infallibility, that reasonably precise and punctilious justice had been done.

Candidates who expect to increase their chances of selection by coming to Hanover for an interview should not be encouraged to incur such expense unless they are personally eager to visit the college and discuss their problems. We are delighted to see and talk to them; but, drawing as we do from a nation-wide, and to some degree world-wide, constituency, we could never expect to see more than a fraction of them personally (even though the director and assistant director are now spending at least 75% their time during office hours on such interviews); and in these circumstances, weight cannot be given to these interviews in selection. Our alumni interviewing system is an admirable substitute.

As for a multitude of "recommendations," one well-known admissions director declares that his selections are made by hefting all the folders and throwing away the heaviest ones. There is more than a little validity to that procedure. When letters from friends-of-friends begin pouring in from all over about a candidate, you can't help starting to wonder what's wrong with him. Two or three letters from persons who really know the candidate well are helpful; letters from friends of his father add nothing to our picture of the candidate.

The preferential status enjoyed by candidates, for geographical or other reasons, is useful to them only if they fall in the marginal group, where it will gain admission for them in preference to other candictates of equal qualifications. There are no "quotas," whether for states, cities, schools, or any other groups.

So much for a very fragmentary account of how the system works.

SONS OF ALUMNI

Now we come to the question of sons of alumni. I almost said "problem"—but that would be grossly unfair. This group is anything but a problem. Through the years of my association with the College, I have looked through the lists of class officers, of athletic teams and captains, of men of distinctive scholastic accomplishment, and have found a more than liberal sprinkling of names of sons of Dartmouth men, and I am sure that this group has contributed to the life of the College far out of proportion to its size. All our experience with Dartmouth sons leads us to expect more rather than less of them, and the College would be incalculably the poorer without their contribution to college life. Furthermore, there is an intangible thing of great significance to the spirit and tradition of the College in having these threads of family tradition run through successive generations—often many of them.

The problem in this connection arises with the sharp increase in the number of applications, the concomitant increase in the number of disappointments, and the effect of these on the morale of the alumni body. The size of Dartmouth classes just about doubled during a brief period of years in the early 20's. Now the sons of these classes are just beginning to come of college age in substantial numbers and the doubling of the number of alumni-son applications is now well along. This year there were 250 alumni-son applicants; eventually there will be 350, perhaps more. Now, just statistically, doubling the number of applicants means the doubling of disappointments, without going into the question at all of raising the criteria which must be applied to this group. These disappointments inevitably produce wide repercussions through the alumni body.

With the number of alumni-son applicants reaching such a large figure, one may well ask the question whether it would be a good thing or a bad thing to have a class composed of from one-third to one-half sons of alumni. I think this is a question which is arguable and I am not going to try to answer it. Such a situation would have both its assets and its liabilities. The question is, to some degree, hypothetical and is not the real one which we must face up to.

The real question that we all must face up to with honesty and courage is the question whether alumni-son candidates must be expected to approximate the going competition for admission. There is no question which I have thought more about during the past year than this one.

I can see only one possible answer—that alumni sons must very closely approximate the going competition. If we turn away clearly superior candidates in these substantial numbers in order to admit alumni sons of lesser qualifications, I cannot see how it could have any other effect than to launch a steady deterioration of the College's standards and an inbred quality in the College which would, in the long run, be disastrous—an inbreeding to weakness rather than to strength.

Moreover, we cannot maintain decent relationships with the schools if we pass by their top-quarter boys of fine all-round qualifications in order to pick up thirdquarter alumni sons. The natural speculation of the headmasters and principals in that situation is whether we are running an educational institution or a Dartmouth Club, and this question has actually been presented pretty straight a couple of times. One schoolman wrote me in a mood of sympathy: "I understand your situation there at Dartmouth and I shall not encourage any boys to apply for Dartmouth who do not have Dartmouth connections." It is clear what would happen to the College if this impression got a wide and firm hold in the schools.

Painful as is the necessity of facing this problem, we have got to face it squarely. I can see only one possible answer: that the utmost point to which preference can go is to give admission to a preferred candidate over another candidate of approximately equal qualifications.

President Dodds of Princeton sent a letter to all Princeton alumni last April. The following paragraph is quoted to indicate the extent to which Princeton has likewise been facing up to questions of policy relating to applications from sons of Princeton men:

"The problems of the Committee on Admission would be simplified greatly if the University could admit every applicant with Princeton affiliations without reference to the credentials of other applicants. But I know that very few Princeton alumni would countenance a policy which would cut us off progressively from the rest of America. Convinced, as we are, that Princeton provides a superior education for responsible citizenship, we should be unfaithful to our stewardship, unworthy of the confidence of alumni and others who have demonstrated their faith in Princeton, and remiss in our duty to the country if our qualifications for admission were not fair and equitable to all, and were not based in each case on capacity, attainment, character and personality as demonstrated in free and equal competition."

You will find some alumni who will argue seriously and apparently with honest conviction that every son of an alumnus ought to be given the opportunity to flunk out of Dartmouth. Obviously, from what I have said, I do not consider that defensible or even possible College policy. Not only can we not afford to admit men who are not pretty clearly able to carry college work at a minimum level, but we cannot in the long run afford to admit those who do not measure up to the prevailing competition. What happens otherwise was indicated in a recent meeting of the Committee on Administration when four out of five of the problem cases before the Committee were alumni sons.

I wonder whether those who argue for the flunking-out privilege have considered this carefully from the point of view of the effect on the alumnus and on the son. An alumnus has just written me from Tacoma commenting on some of these questions. He says:

"A number of years ago I was talking to the father of a son who had been admitted to Dartmouth, but who was later separated because of scholastic difficulty. The father told me he felt that it would have been better if the boy had never been admitted. I think he felt that though it would have been a disappointment not to have been admitted, it would have been much better in the long run to have accepted that disappointment, rather than later being faced with the frustration of just not being able to make the grade. There was more danger of permanent frustration from the latter than from the former.

"When I was in San Francisco last May, I talked with a friend of mine who graduated from Yale, and in the course of the conversation, I mentioned that his boy would probably be going there soon. He remarked that the way things were nowadays, he didn't know whether the boy could get into Yale or not. So I guess other institutions are having their problems also."

Actually, of course—and this is almost impossible for an alumnus parent to recognize—after we consider each alumnison candidate as an individual case (and heaven knows we do consider them at length and with care and prayer) we also have to consider them as a group. The alumnus whose son has been turned down almost invariably will argue that even if his boy has no better than a 50-50 chance to survive at Dartmouth, we can afford to gamble on him. If there were only one such alumni son, or even if there were only six or twelve, we might out of deference to a father's lifetime devotion and service to the College, accede to his request and make the gamble. But when you have more than one hundred of these candidates who, in relation to the prevailing competition, are submarginal (and this number will rapidly increase), you are gambling with stakes that are far too high for the College to afford.

This is in essence the alumni-son question and I am confident that the conclusions indicated fairly represent the position of the President and Trustees. The Alumni Council at its meeting last June considered this question. The Council's Committee on Admissions and Schools in its report commented: "Dartmouth has always been an alumni college, but the College has grown and changed since our day. Due to the increase in the number of applicants for admission to the College and to the greatly increased numbers of Dartmouth sons applying for admission, this committee feels that Dartmouth fathers and their sons must recognize that from here on the sons will have to meet keener competition for selection. The Selective Process, in other words, which has always given preference to Dartmouth sons, should continue to do so but the sons will have to meet the competition of that year, both in regard to academic and other factors of the process. We hope and believe that Dartmouth sons should always receive preference, other things being equal or nearly equal." The Council vdted to approve the report of the Committee and "to endorse specifically the portions of the report dealing with the admission of Dartmouth sons."

From the alumni relations point of view, there is an educational job to be done among alumni parents. For example, one Saturday afternoon last December an alumnus telephoned me and asked if it were necessary for his boy, as the son of an alumnus, "to go through the motions of filling out these application forms that you have sent to him?" As it turned out, the boy was one of the most hopelessly unprepared among all the 6,000 applicants this year. When he was turned down, the father was quite shocked and very, very angry. Another alumnus wrote to say that he had two sons and to ask whether he should enter applications for them or whether they would automatically be admitted when they came of college age. Now this sort of thing must seem almost incredible to those of you who are closer to the College, but it obviously exists, and rather widely.

I hope alumni will continue to make their sons want to go to Dartmouth more than to any other place, but they must, at the same time, make the boys realize that getting into Dartmouth is ajob they have to work at. As they approach college age, if their aptitude for college work seems in doubt, these parents must prepare themselves and prepare their sons for the fact that there are alternatives to a Dartmouth education.

In conclusion let me say that we have not yet got trouble enough. Even after these hectic months, 1 still hold with Browning, as I have twice said to the Alumni Council, that our reach should continue to exceed our grasp. We do not want, heaven knows, any more applications per se, but we do want and will always want more of the best ones. We cannot, as the maxim goes, stand still without going backward, and we cannot stop until all the best boys from all the schools throughout the country want to go to Dartmouth. This, of course, can never happen; but instead of selling out for our share of the best boys, we must always be out to get as much more than our share as we can possibly get.

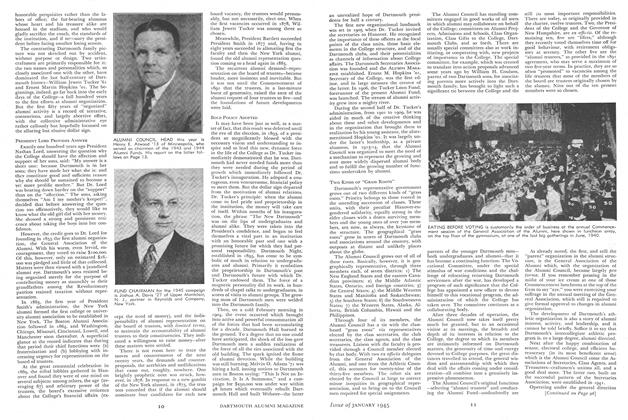

DIRECTOR OF ADMISSIONS

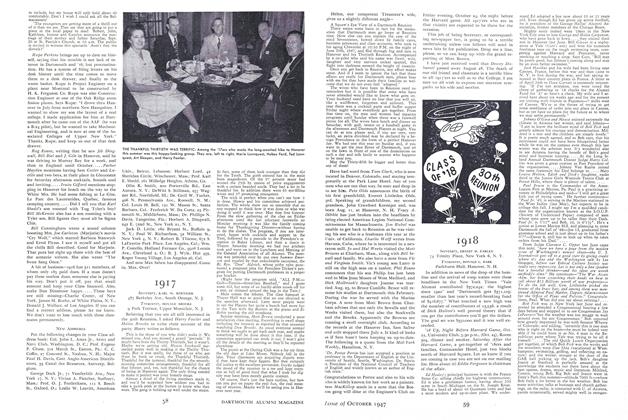

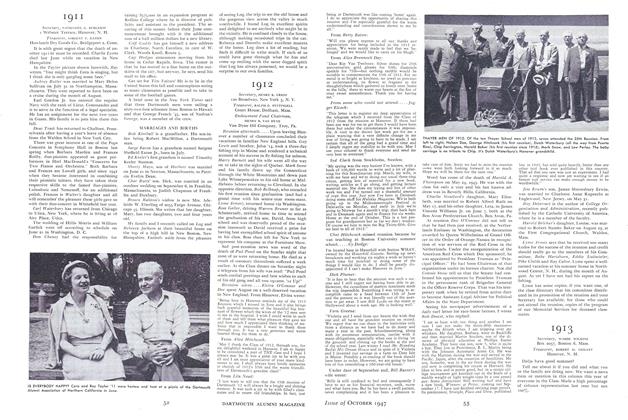

STILL BREATHING HARD from the herculean task of picking the Class of 1951 from some 6,000 applicants, Albert I. Dickerson '30 (left), director of admissions, and Edward T. Chamberlain Jr. '36, assistant director, turn to the 1952 application drawer, already bulging with thousands of names.

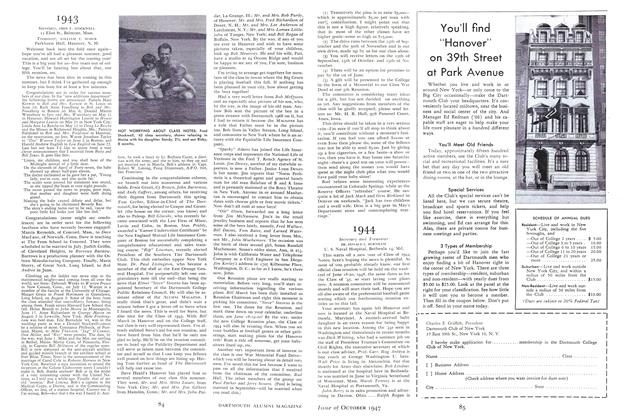

A COMPARATIVELY CALM MOMENT in the Admissions Office, where the numerous details of Dartmouth's Selective Process are handled by a sizable staff, only partly shown here. Eleazar Wheelock, who had admission problems of his own, of a different sort, looks on from the wall of the old faculty room.

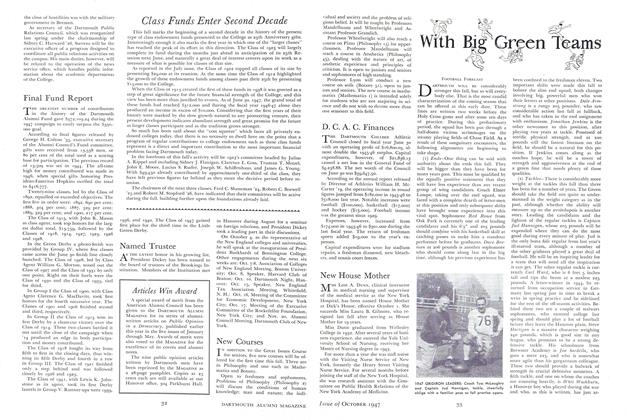

TWO DISTINGUISHED DARTMOUTH TEACHERS: Poet Robert Frost '96, George Ticknor Fellow in the Humanities, and Leon Burr Richardson 'OO, New Hampshire Professor of Chemistry and senior member of the faculty. Behind them are Sidney Cox, Professor of English, and Donald L. Stone, Professor of Government.

The old joke to the effect that whenever two Dartmouth men get together they form a Dartmouth club may soon have to be amended to read that they compare notes on the admissions situation. Certainly alumni interest in this subject is widespread, and the editors of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE, in keeping with their editorial statement of last June that it is wholly desirable for the alumni to have a full and authoritative statement about the admissions situation, have prevailed upon Mr. Dickerson, snowed under as he is, to write this article. His highly readable discussion of Dartmouth's handling of this toughest of all administrative problems will give our alumni readers a great deal to think about and will clear up a number of misconceptions that to some extent prevail among Dartmouth men, not to mention the general public. Rather than present Mr. Dickerson's necessarily long analysis in two installments and run the risk of destroying its unity, the MAGAZINE has made space available for the entire article in this issue.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHE GREAT ISSUES COURSE

October 1947 By THOMAS W. BRAD EN '40 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

October 1947 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1915

October 1947 By SIDNEY C. CRAWFORD, CHANDLER H. FOSTER -

Class Notes

Class Notes1913

October 1947 By WARDE WILKINS, ROBERT O. CONANT -

Class Notes

Class Notes1943

October 1947 By FRED F. STOCK WELL, WILLIAM T. MAECK -

Sports

SportsFootball Forecast

October 1947 By FRANCIS E. MERRILL '26.