Dartmouth's Educational Experiment, Launched This Fall For All Seniors, Attracts Wide Interest and the Support of National Leaders Who Are to Lecture in the Course

WHEN THE BOMB EXPLODED Over Hiroshima, higher education in the United States was already examining itself with a critical eye.

Harvard's President Conant liad remarked that the purpose of education was "not to develop an appreciation of the crood life in young gentlemen trained to the purple " A Harvard faculty committee had issued a report which ended a little uncertainly as though the members agreed with him but couldn't think of the reasons. At the root of the discussion in all the colleges was an old question made new by the war: Shall a man be trained to work for his own welfare or for the public welfare? Is the end of education one man or all?

Perhaps the common tragedy of the war had not basically altered the common American standard for success in life. At the war's end the colleges were still turning out citizens who regarded restricted residential areas and complex gear systems as primary aims.

In the tall shadow of the bomb these people were revealed as the failures of higher education. Because they are frequently mistaken for educated men and are themselves ignorant of the deception, they are far more dangerous and subversive than the less influential ten per-cent of United States citizens who were revealed in a recent and unpublicized poll to be so innocent as never to have heard of the United Nations.

The colleges then are guilty of permitting an error. The bomb having settled once and for all the question which education was debating, it is education's responsibility to see that the error doesn't occur again. Now and for some time to come the primary duty of an educated man is to help his world survive.

At Dartmouth the faculty had not concluded its curricular revisions when the explosion came. It had the "benefit," if it may be called that, of knowing more than earlier deliberators at other institutions about what the postwar world would be. Its reaction was direct. In February of 1946, just four months after its new President took office, it heard him explain and immediately approved his idea for a course called "Great Issues." He then appointed a Steering Committee to put his plan into practice.

The well-known enthusiasm of the President of Dartmouth College is at its most contagious when he is in the middle of the Great Issues idea. He has a habit of piling his thoughts on the subject about waisthigh in front of him, so to speak, and then hammering them with a long forearm, saying, "If we can only get them to see the distinction between " His first explanation of Great Issues is reported to have made the most exciting faculty meeting in years.

By this time, alumni will have heard of the Great Issues course through the editorial praise which has greeted it all over the country. The Carnegie Corporation has agreed to help finance it with a grant of $75,000 over a three-year period. Three other colleges have adopted it in whole or in part. So has a civic-minded women's club. Parents of Dartmouth seniors have written to inquire whether they can take it by correspondence, and a graduate student in India writes that he wishes to enroll this fall and will arrive bv air.

From the outline reproduced on the next page, alumni can make a rough estimate of what Dartmouth seniors will be thinking about this year, but the aims of the course and the impact it ought to make cannot be shown on a chart.

In essence, Great Issues is a response to the fact that the compartments of thought and knowledge which man has erected not only in the colleges but less precisely in the world have burst under the pressure of the very issues which thought and knowledge have produced. These issues have to do with survival and no man has a right to ignore them.

A carefully guided consideration of these issues is therefore required of all Dartmouth seniors who can complete it in two consecutive semesters. Thayer School, Tuck School and Medical School men are not excepted. The class will meet three times a week. On Thursday mornings they will hear a member of the Dartmouth faculty explore the history of the issue. On Monday evenings the guest lecturer will try to state the problem in its current implications. On the following morning, President Dickey and the speaker of the previous evening will lead the class in discussion.

Obviously the names of the guest lecturers—Archibald MacLeish, Alexander Meiklejohn, Congressman Herter, Joseph Barnes, and President Conant, to mention only a few—are an exciting aspect of the course. But there is a second consideration involved which goes beyond the presentation of the issues in the classroom and it has aroused considerable discussion.

None of the issues with which the seniors will deal is made less urgent by the fact of their having studied them. They may well go on studying them for the rest of their lives. For this reason Dartmouth finds itself trying to bridge the gap between education on the college level and education on the adult level.

The challenge is fascinating. How should a responsible adult citizen keep himself informed? He is under constant pressure to read newspapers, periodicals, and the literature of private interest groups, and under considerably less pressure to read the enormous mass of information produced by his government, some of which is more worthy of his time. What exactly is the distinction between the good information sources and the bad ones? To be concrete, does the Chicago Tribune inform or misinform its readers?

The technique for meeting this challenge is twofold. In order to help men to the habit of using information resources, the Great Issues Steering Committee had to decide upon a few which in its opinion set a high standard. The class will therefore be held responsible daily for the important news in either The New YorkTimes or the New York Herald Tribune. Among other assignments they will be required to read at certain specific points in the course, John Hersey's Hiroshima, the Acheson-Lilienthal Report and E. B. White's Wild Flag, as well as such basic documents as the Charter of the United Nations, the Communist Manifesto, the Declaration of Independence, and Mussolini's statement on Fascism.

But as adults, men who are now college seniors ought to have their own standards as to how to keep up with their world. The Public Affairs Laboratory which has been installed in Baker Library is intended to help them set their standards. In this room, they will analyze and compare newspapers and other periodicals, trying to determine the accuracy, depth and viewpoint with which they present the issues of the day.

What are the issues which in the year '947 Dartmouth considers "Great"? The Steering Committee which the President named to work out the course in detail consisted of representatives from all the divisions on the faculty. It is worthy of note that these specialists easily reached agreement on a course of study which, like the world it tries to reflect, is no respecter of special fields. Yet a first glance at the issues they have listed in the syllabus may occasion some surprise.

You will not find there that common ailment of lecture programs, the geographical approach which divides the world into certain areas and discusses them as though they were in fact distinct. There is no section entitled Far East, or Germany or Sweden. In the Far East and Germany and Sweden and everywhere else in the world men are now engaged in a struggle of ideas, and in all the world the ideas are the same.

Neither will you find in the syllabus a pro and con approach. Posing representatives of American Communism and American Fascism on the same platform and letting them call names might be good carnival but it is not education.

The Steering Committee early decided that the most important issue should be considered first and that the rest of the course should grow out of the consideration of that first or central issue. This decision is not academic. The yawning gap which has divided our world since the end of the war and has roots which creep far into history is in fact the central issue of our time. It is a part of every man's thinking. It bears upon all other questions from science to art and from religion to government. It was even mentioned by a Southern Congressman in connection with Brooklyn's decision to put Jackie Robinson at first base.

The Steering Committee has called this central issue "Modern Man's Political Loyalties." It did not say Russia vs. the United States or Communism vs. Democracy because these titles explain away too many questions. Some of them were asked by Archibald MacLeish, in one searching paragraph of an extremely helpful memorandum which he prepared for the Committee's use about midway in its work: "What is the real issue? Is the world in the throes of a vast civil war as the Marxists believe? Is it split by a conflict between two nations, one of which uses Communism as a fifth column as the reactionaries here seem to believe? Or are we observing the collapse of a civilization and the disintegration under that collapse, not only of nineteenth century capitalism but of the Marxist nostrums invented to replace capitalism? Against what is the revulsion of our time in all countries really directed?— Against the ruling classes as the Marxists and Socialists believe, or against the bureaucracies and the parties as the individualists contend, or against the sordidness and cheapness and mechanization and frustration of industrialized life as some psychologists have argued? In other words, what is the real character of the unrest of our time? On what actual choice do our lives depend—and the future of our world?"

Once it was decided to pose the central issue immediately after the introductory lectures by Mr. MacLeish, the job of the Steering Committee was to anticipate and to place in logical succession the component issues which a student will face as he considers the political loyalties of man, the reasons for them and the manner in which they are at war.

These component issues which derive their urgency from the central issue and at the same time help to explain it are listed under the four remaining sections of the course.

To STUDY ALL ASPECTS OF ATOMIC ENERGY

The first of these, section three, is called The Scientific Revolution and the Radical Fact of Atomic Energy. Here is the catalyst which has made the division in our world a matter of survival. The lecture titles indicate more clearly than those in any other section of the whole course that the study of a public issue necessitates a breakdown of academic divisions. Dartmouth seniors will study atomic energy in its scientific, economic, political and social aspects and as a problem in the ethics of man.

Section four, International Aspects of World Peace, opens more paths to the discovery and solution of the central issue of our time. A study of the United Nations, of the proposals for World Government, of national versus international methods of handling international problems follows logically from the appreciation of what the fact of atomic energy has done to our world.

Section five, American Aspects of World Peace, brings the central issue home. Lenin declared many years ago that Americans would never win a struggle against Communism because they could not create a working democracy at home. It is now apparent that we shall have to meet the challenge. In this section are some of the issues—civil liberties, the rights and responsibilities of labor, the function of planning, the efficiency of governmentwhich are involved in the job.

MORAL CONSIDERATIONS PERVADE COURSE

In a sense the final section of the course called What Values for Modern Man? is a double assurance. Throughout the year the Steering Committee intends that the student shall be kept in touch with the problem of right and wrong, not only in the expedient sense, but in the moral sense as well.

The distinction is important and is worth making clear. We began mass bombing because it was right in the expedient sense; we dropped the bomb on Hiroshima because it was right in the expedient sense;

within a short time it will be possible for us to wipe out the Russian people, and there are those who privately hint that this will be right in the expedient sense.

But what is right in the moral sense? We fought a war for moral considerations, and it would be strange if we had lost them while we were winning it. These moral considerations are personal—they spring from persons out of a regard for persons. For that reason it seemed necessary to point out specifically that the Great Issues of our day are not only political, economic, and scientific but are of the hearts and faiths of men, that when a senior leaves a college he takes with him not only accepted knowledge but accepted ideals.

The Great Issues Course is an attempt to help make these ideals count. Whether the course is successful or not, that task remains the chief purpose of education in the atomic age.

EXECUTIVE SECRETARY OF THE COURSE

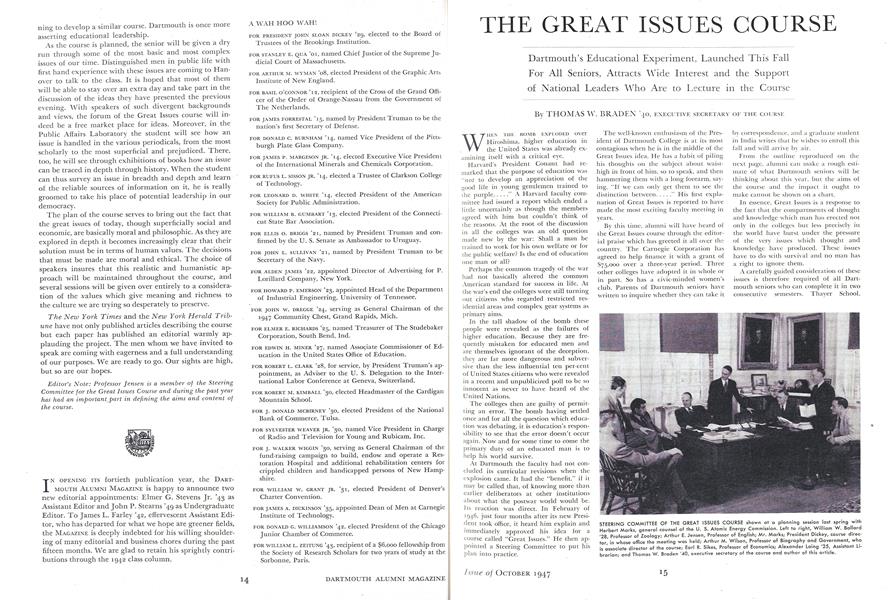

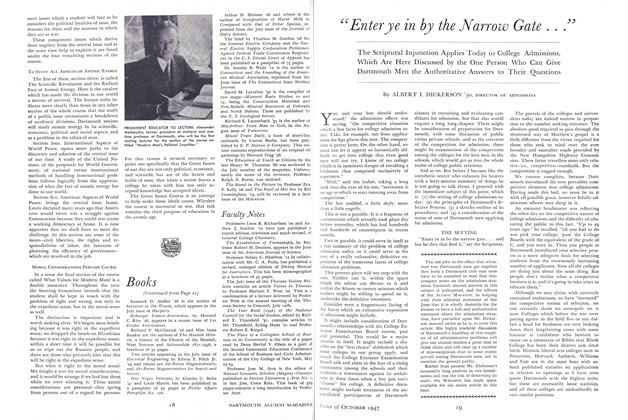

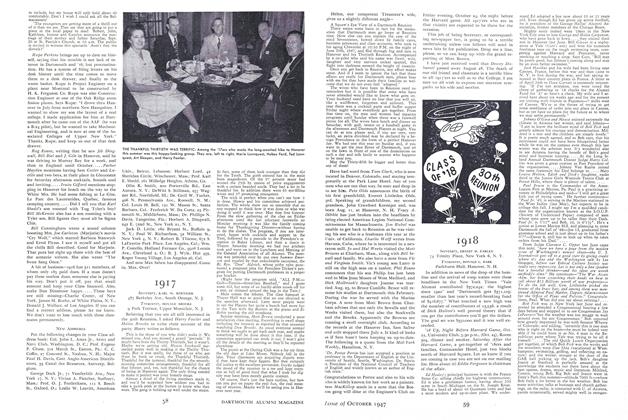

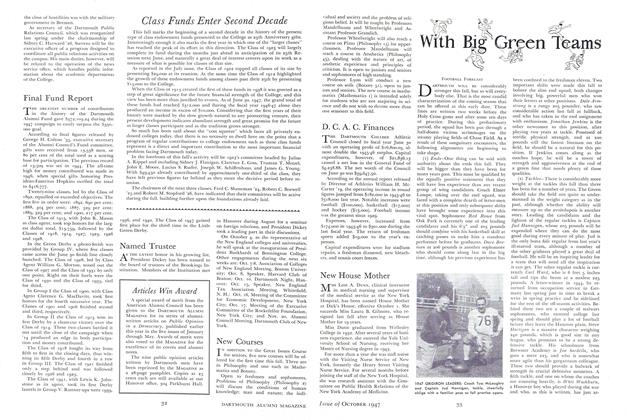

STEERING COMMITTEE OF THE GREAT ISSUES COURSE shown at a planning session last spring with Herbert Marks, general counsel of the U. S. Atomic Energy Commission. Left to right, William W. Ballard '28, Professor of Zoology; Arthur E. Jensen, Professor of English; Mr. Marks; President Dickey, course director, in whose office the meeting was held; Arthur M. Wilson, Professor of Biography and Government, who is associate director of the course; Earl R. Sikes, Professor of Economics; Alexander Laing '25, Assistant Librarian; and Thomas W. Braden '40, executive secretary of the course and author of this article.

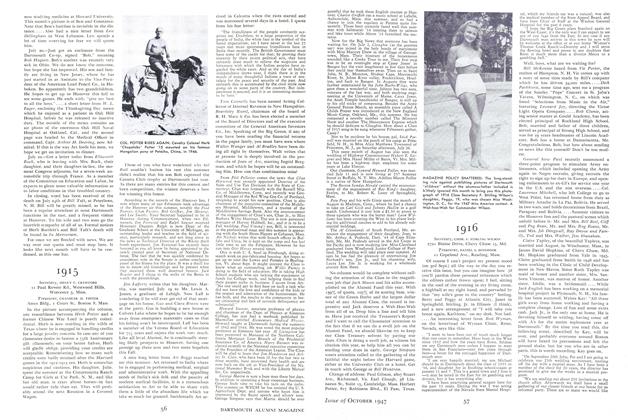

TO DELIVER OPENING SCIENCE LECTURE: President James Bryant Conant of Harvard University, whose talk "On Understanding Science" will open consideration of the "great issue" of atomic energy.

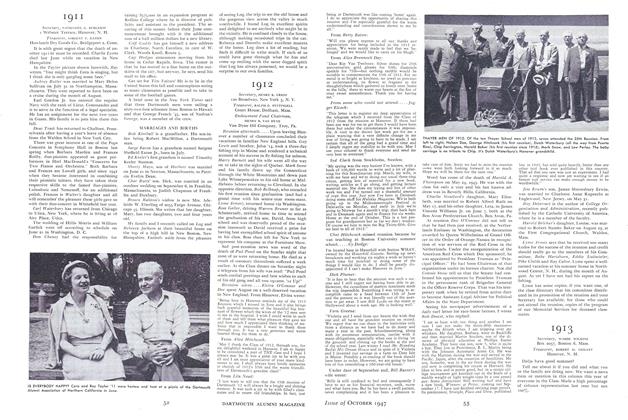

PROMINENT EDUCATOR TO LECTURE: Alexander Meiklejohn, former president of Amherst and onetime professor at Dartmouth, who will be the first visiting lecturer for the section of the course entitled "Modern Man's Political Loyalties."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

Article"Enter ye in by the Narrow Gate ..."

October 1947 By ALBERT I. DICKERSON '30, -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

October 1947 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1915

October 1947 By SIDNEY C. CRAWFORD, CHANDLER H. FOSTER -

Class Notes

Class Notes1913

October 1947 By WARDE WILKINS, ROBERT O. CONANT -

Class Notes

Class Notes1943

October 1947 By FRED F. STOCK WELL, WILLIAM T. MAECK -

Sports

SportsFootball Forecast

October 1947 By FRANCIS E. MERRILL '26.