By Robert Frost '96.Henry Holt and Cos., 1947, pp. 39, $2-50.

To a freshman who asked him brightly what new hope he was bringing to us Robert Frost intimated that he had not exhausted the old hope yet. A Masque of Mercy, like A Masque of Reason, is a free fantasia on Biblical themes. To the old Puritan still lurking in us the fantasia may seem too free, too irreverent, too playful, too frivolous. But Chaucer, if he could fathom our twentieth century idiom, would not find it so. I say Chaucer because Jesse Bell, like Job's Wife in A Masque of Reason, curiously reminds me of the Wife of Bath: "You don't catch women trying to be Plato," Job's Wife says; says Paul, the "analyst" or "annalist" of this piece:

Jesse Bel's a girl Whose cure will lie in getting her idea Of the word love corrected.

These quotations will perhaps give a taste of the chaffing, the banter, the punning—"So you've been Bohning up on Thomism too" that characterize both poems. The lightness and the casualness, however, do not conceal the fact that Frost's poetry has grown increasingly concentrated, elliptical, gnomic and allusive—A Masque of Mercy is as variously allusive as The Waste Land, for example. The flippancy is a mask behind which the eyes of a seer look out upon a profoundly troubled world and from whose papier-mache lips issue words of wisdom, humility and compassion. The whimsical form of the poem fits the puzzle of the theme—what can make injustice just?—and mirrors the paradox of a world ready to spread the brotherhood of man by atom bombs. Rather than illustrate the point by lines pertinent to the main theme let me close by quoting Jesse Bel, that "solitary social drinker":

The saddest thing in life Is that the best thing in it should be courage. Them is my sentiments, and Mr. Flood, Since you propose it, I believe I will.

The flippant allusiveness of the last two lines will not blind the percipient to the poetic majesty of the first two.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleMEN VS. MICROSCOPES

December 1947 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Article

ArticleHANOVER'S NOTED CLINIC

December 1947 By ALICE POLLARD -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

December 1947 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917

December 1947 By KARL W. KOENIGER, DONALD BROOKS -

Class Notes

Class Notes1919

December 1947 By J. K. HUNTINGTON, MAX A. NORTON -

Class Notes

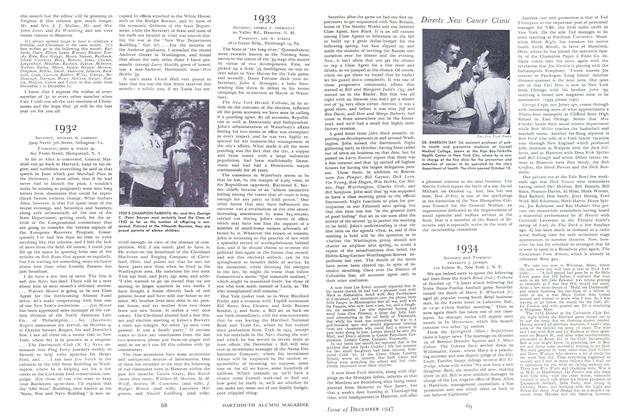

Class Notes1934

December 1947 By FRANKLYN J. JACKSON

STEARNS MORSE.

Books

-

Books

BooksANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY OF SPEECH.

July 1960 By CARL D. ENGLAND -

Books

BooksSECOND WIFE.

DECEMBER 1963 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Books

BooksWHAT DO UNIONS DO?

SEPTEMBER 1985 By Mark Woodward '72 -

Books

BooksFROM THE ISLAND

JUNE 1932 By R. L. Woodcock '33 -

Books

BooksDeepening Interdependence

April 1976 By THEODORE C. ACHILLES -

Books

BooksTHE AMERICAN DISSENT: A DECADE OF MODERN CONSERVATISM.

MAY 1966 By VINCENT E. STARZINGER