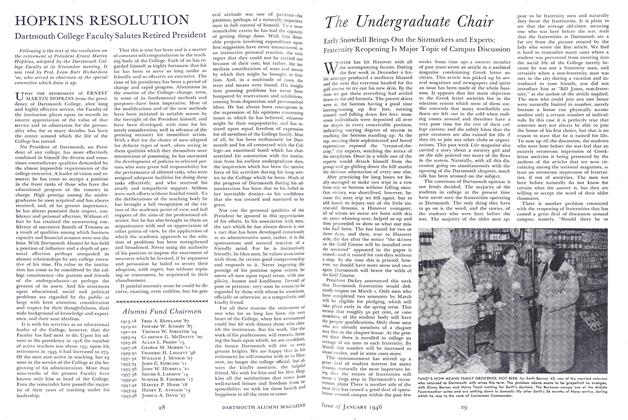

The Father of Dartmouth's Famous Poet Laureate Was an Exponent of liberal Ideas in Education and Served as a Major General in the Civil War

ON SUNDAY MORNING, July 17, 1763, Ebenezar Smith, John Slafter, and "a young Mr. Hovey" buried Jacob Fenton in the newly granted township of Norwich. They peeled a large basswood and placed their friend within its gleaming bark. With thongs of twisted elm they bound the covering and laid the body in the meadow-land beside the Connecticut. So they first broke the soil of Norwich and planted this Mansfield body within it.

Who "young Mr. Hovey" was we do not know. Smith, Slafter, and Fenton were proprietors of the town. John Slafter, who had been drummer boy under Israel Putnam in the French War, served under Rogers in the Rangers on the Crown Point Expedition, and climaxed four years against the French by being present at the capitulation of Montreal in 1760, had been sent by the people of Mansfield, Connecticut, to scout the township granted by Governor Benning Wentworth on that same day in 1761 on which Hanover, Lebanon, and Hartford were granted to their proprietors. In the summer, he returned with his uncle Fenton and his friend Smith. Since he married Elizabeth Hovey before the migration up river in dugout canoes in 1767, it is possible that "young Mr. Hovey" was one of her brothers, either James, who owned land in Norwich and three shares of land in Hanover, or Aaron, who bought four parcels of land in Norwich. Slafter liked Hoveys, as is proved by the fact that when his wife died he married her younger sister, and he may have taken one of the boys along as unofficial companion.

The probability, however, is that "young Mr. Hovey" was James, on an independent scouting trip across the river. We know that in the next year he was one of a party of nine who came to Hanover in June to lay out the first division of one hundred acre lots, and that in October he was again one of the group of twenty-four who cleared roads in the town, for which he received one pound, sixteen shillings. In December he bought three shares of land in the yet uninhabited place. Two years later he died of tuberculosis at the age of 28, so that his interest never culminated in migration.

In 1767, the first year of settlement, his father, Edmund, came to Norwich, where he now lies in the old burial ground. Five of his children came with him and lived in either Norwich or Hanover, and other relatives were nearby. His nephew Roger, who as a 17-year-old boy had walked from Mansfield to Boston to fight the British, settled on the Parade in Hanover; married the daughter of Edmund Freeman, the first settler; bought a stock of iron with his soldier's pay and wrought the bars, bolts, and hinges of Dartmouth Hall.

Amos, a son too young to have been a member of the clearing party of 1763, lived in Norwich for a time and at 24 pushed on to Thetford.

Since his son Alfred was remembered as a man of will and conviction, one must lay his shifting life to the restlessness which Richard Hovey later claimed had sent each of the eight American generations into a new place. He moved out to Greene, New York, and in half a dozen years returned again. At his wife's urging, he went into debt for a farm, raised sheep and cattle, and paid off the debt; but when she died he sold the place and went into lumbering in Dorchester, New Hampshire. Finally he moved on to Wisconsin to join one of his sons.

By his sweet-voiced wife, Priscilla Cushman Howard, who brought into the family ancestors of whom her grandchild Richard was to be very proud, he had seven sons and four daughters.

The boys entered the spare life of simple living and high endeavor of the Yankee farmer. About a mile away as the crow flies, but another mile as a boy walks in hilly Vermont, was Thetford Academy, that extraordinary seed-bed of ability. Not many miles to the south was Dartmouth, founded where relatives had given land to which Dr. Wheelock was welcomed by the old friends who had come north a few years before him. Three of the boys graduated from the College: Amos, Dartmouth 1842, who after teaching became a farmer and land surveyor in Darlington, Wisconsin; Alvah, Dartmouth 1844; and Charles Edward, Dartmouth 1852. Alvah graduated from divinity school, became successively instructor in Hebrew, Librarian, Professor of Church History, incumbent of the chair of Christian Theology, and finally Presiident for 31 years of Newton Theological Institute. He was trustee of Worcester Academy, Brown University, Wellesley College, and the author of twelve learned books and many articles.

Charles Edward Hovey, the subject of this sketch, lived the life of a Vermont farm boy in the large unpainted house which still stands some two miles south of Thetford Hill. At fifteen he was already a teacher "high up among the green hill," as he said, where some of the pupils were older than the teacher. For this respectable agony he earned $9.50 and board a month. When the family moved to the wilder township of Dorchester, he was put toteaming and lumbering. "For a time he alternated between building barns, tending sawmills, rolling logs, carting boards, and blacksmithing." After such years of work. he had earned his right to education, and prepared for college under his uncle, his brother Alvah, and, at Thetford Academy, under the great "King Hiram" Orcutt, Dartmouth 1842, under whom the school reached wide fame. When he was 21, he entered Dartmouth College, but like so many of his classmates, he left for a term of teaching each year. At this he worked himself up from $28.00 and board a month to a place at Newton which paid him $40.00. So, when he graduated from Dartmouth in 1852, he was already an experienced teacher and man of 25. After graduation he went to Framingham Academy as principal and instructor. One of the preceptresses at the school was 18-year-old Harriet Spofford, a bright graduate of Abbott Academy. They were good teachers and through the Secretary of the Massachusetts Board of Education they were invited to positions in Peoria. They were married on the day they left for Illinois.

The new school for boys which they joined became famous in a short time for its debates, arguments, and free school system. Other schools followed its liberal example, and the young principal found himself a leader in educational movements. He couldn't rest easily in his position in a private school when he faced the wretched conditions in the public schools and saw the school children suffering what he considered a wrong. He went to work, got a new school board elected, won the newspapers to his side, bought new buildings, and as principal and superintendent pushed his reform. "Night and day, weekends and Sunday, I worked on."

No real advance was possible without more trained teachers. Yankee girls were going West fast, but two thirds of them were married in five years. The result was more pupils. Grumblers said the state got nothing out of this but more Abolitionists. The obvious solution was a normal school to educate their own teachers, but that toopushing. First the teachers formed the Illinois State Teachers Association with Hovey as its president, and, second, established The Illinois Teacher, with Hovey as editor, to give spread to their ideas and break down the tax-payer's resistance to free education. With these means Hovey fought for a normal school "on the stump, in the lobby." Finally he got the bill through the legislature and in June, 1857, he was head of a university on paper.

Bloomington outbid Peoria and the north section of the town became Normal. The cornerstone of the main building, itself the center of a great quarrel, was laid in September, 1857, but the panic of that year dried up the subscriptions which had been made. Building had to stop. By starting a land boom with considerable skill and by pledging his word, though it later brought him to law, Hovey got the building going again. But though construction stopped, education could run on sheer faith and energy. Moving into shacks and cabins, Hovey and his assistant started school with nineteen pupils. By the end of the year there were one hundred and twenty-seven. It was a very free school with no rules and little government. The first subjects of debate show the liberalism of their mood: compulsory attendance, expression of political sentiments by teachers, manual labor.

Through these years Hovey never let up in the work. He was doing two, three, or four jobs at once. When he was too tired to go on, he lay on the floor with a dictionary under his head until he could work again. His high faith, his energy, and his recognized fairness brought success. The school still stands.

In the summer vacation of 1861 Hovey went to Washington. He saw the battle of Bull Run, and immediately asked permission from Lincoln, whom he knew, to raise a brigade. Enlisting as soon as he reached home, he raised two companies from his students, with whom eight companies from students and friends of other institutions joined. They voted to recommend Private Hovey as Colonel, and Governor Yates appointed him to the rank as from August 15.

This regiment, the 33rd Illinois, was one of the most extra-ordinary fighting units any war has seen. Perhaps its only rival was the group made up of Dartmouth and Norwich students. Known variously as the "Normal Regiment," the "Teacher Regiment," or the "Brain Regiment," it owned a high level of intelligence and morale. As one of its captains said, "The high intelligence and social culture which prevails among the privates make discipline an easy task." "Pride of character" and esprit decorps were the regiment's acknowledged qualities.

Mrs. Hovey followed her husband in soldier's cap and coat until ordered home. In the high-studded angular house they had built in iB6O and around which they had planted elms and maples, she nursed the sick and protected fugitive slaves. One negro woman came down with smallpox and she attended her through the sickness. From the windows she and her sister used to wave to the troops going south on the Illinois Central Railroad a few blocks to the east.

Colonel Hovey's first battle was against a badly outnumbered Confederate force at Fredericktown, Missouri, in mid-October. Here his men named one of the outposts "Fort Hovey." On the march down through Missouri and Arkansas he was given command of the brigade.

At Cache River, Hill's Plantation, on July 7, 186 a, Hovey was in advance of the army with about five hundred men. He ran into five thousand Confederates under Rust and was forced back. Forming an ambush he attacked and finally repulsed the enemy. General Steele reported: "The Rebels did not stop running until they had gone eight miles south of Little Rock." Even if one cannot say "one man and four hundred boys routed six thousand," as has been said, it was a good piece of tactical cleverness. Hovey lost only seven men to the Confederate loss of one hundred and ten. In September he was made Brigadier General.

Under General Sherman he and his men moved down river from Memphis and up the Yazoo for the third attack on Vicksburg. They landed on the flats north of the city on December 26. Between them and their object was an almost insuperable terrain of bottom land, swamps, lakes, and old river beds, with a few ridge paths overlooked by guns and rifle pits. Steele's division, of which Hovey commanded one brigade, was ordered to land above the mouth of Chickasaw Bayou and advance. So tortuous and difficult was the way through the swamp that the negro guide made a wrong turning and they lost a day in countermarching. On the 28th they skirmished with enemy outposts, but it was so impossible to advance they were drawn back. On the 29th a desperate attempt was made to advance by storming the higher ground. Hovey's brigade was in support, but the loss was so heavy from rifle fire and cross fire of grape and cannister that the advance fell back before the brigade came into range. Grant's cooperation from the south hadn't materialized and Sherman feared the rain which began to fall, for a rise of a few feet in the river might drown his troops in the old river channels. So with loss of I 176 to 207 of the enemy, Sherman embarked his troops and dropped down the Yazoo. It was a gallant and able action but a hopeless one. How hopeless no one knew until it was over. It took another seven months of siege before heavily invested Vicksburg fell.

Sherman was relieved of high command by McClernand, a political civilian appointed by Lincoln. It was his idea to strike up the Arkansas River to Arkansas Post and destroy the fort which commanded the river some forty miles above its entrance into the Mississsippi, and so free the line of operations from trouble from west of the Mississippi. This was an amphibious att'ack using iron-clads, gun boats, and tinclads, as well as troops. The fleet got into position while the army moved up to the edge of the lowland about 500 yards from the enemy. Hovey commanded the brigade on the extreme left. There they lay for the night, without fires or covering in the January chill. In the morning the concentrated fire of ships, shore batteries, and rifles raised the white flag over the fort. The hot commander of the entrenched brigade facing Hovey's men, however, refused for a time to surrender, claiming later that he had had no order. Though it was victory, the Federal troops had lost 1100 men, just eleven times the Confederate loss, though they had taken 5,000 prisoners. Hovey had fought well but was shot through both arms. In March he was made Major General by Brevet for "gallant and meritorious conduct in battle, particularly at Arkansas Post."

Two days after the engagement they went down river in a snowstorm. Hovey, weakened by his wounds, came down with malaria contracted in the swampy morass of Chickasaw Bayou, had to resign his command, and was never again well enough to reassume it. Indeed the next six years were a struggle to regain health.

Rather than choose the safety of his assured place as educator, he chose to chance the law which he had always wanted but which had demanded too much time and money. He went to Washington, while his wife took her son and two-months-old baby to her parents' home in North Andover. There in the old Spofford homestead, where many summers were later spent, they waited until the General, as he was always called, had made a home for them in the Capitol. In Washington Hovey lived as lawyer, hon6rable citizen, and quiet, reserved man. All who knew him respected him, but the home found its center in Mrs. Hovey, "mother of poets," who gave so many young men and writers a second home, despite her work as head of the Division of Correspondence and Records in the National Bureau of Education. Though both had their days full of work, they generously spent many nights carrying on the business of their poet son. Mrs. Hovey typed manuscript; General Hovey wrote letters, sent out complimentary and review copies, copied the dozens of answering letters into a duplicate notebook, and kept the large scrapbooks of press cuttings.

Gradually the romantically handsome officer became an old man. When the Normal University celebrated its fortieth anniversary, he was there, but was able to speak only briefly. He was dying of Bright's Disease, but his strong vitality for weeks refused to let his heart stop.

Finally, in November of 1897, he died, and the Kit Carson Post of the G.A.R. buried him in Arlington Cemetery. His son remembered the sound of the bugle breaking the autumn silence, and Bliss Carman, who had spent so many months as an adopted "boy" within the home, wrote in Decoration Day:

There rests my old friend in his soldier's grave, Old grim idealist with the tender heart, The grizzled head, grey eye, and scanty speech.

And hand that never faltered in the fight Through all the rough work of a long campaign.

God keep you, General, with the heroes gone!

GENERAL CHARLES E. HOVEY '52

PROFESSOR OF ENGLISH

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleFreedom of the Screen

April 1947 By WALTER WANGER '15 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

April 1947 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Article

ArticleA Challenge Still Unanswered

April 1947 By BUDD SCHULBERG '36 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

April 1947 By Charles Clucas '44 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917

April 1947 By MOTT D. BROWN, DONALD BROOKS -

Class Notes

Class Notes1937

April 1947 By JOHN H. DEVLIN, ARTHUR H. RUGGLES JR.

ALLAN MACDONALD

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLETTERS TO THE EDITOR

May 1934 -

Article

ArticleTales of Adventurous Travel

April 1934 By Allan Macdonald -

Books

BooksTHE ISLANDS

June 1936 By Allan Macdonald -

Article

ArticleDartmouth's Rebel Saint

November 1938 By ALLAN MACDONALD -

Books

BooksLEAVE HER to HEAVEN,

August 1944 By Allan Macdonald -

Article

ArticleWEBSTER AT SEA

January 1946 By ALLAN MACDONALD

Article

-

Article

ArticleDeaths

March 1939 -

Article

ArticleWith Big Geen Teams

February 1958 -

Article

ArticleCouncil Ratifies New Constitution

SEPTEMBER 1996 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

April 1938 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

ArticleSMALL HOUSES CLAIM UNITY

November 1934 By Milburn McCarty IV '35 -

Article

ArticleREMEMBER THE GATE

By S. H. Silverman '34