SOME YEARS AGO Archibald MacLeish brought out a book with a clumsy title: America Was Promises. The title still bothers me. Perhaps it is merely the awkward sound it makes; more likely it is the past-tense pessimism. America, for me, continues to promise. One of our country's more intriguing characteristics is the lag between promise and fulfillment. This is a land of golden words and inspired principles—and the fact that the Declaration of Independence and some remarkably enlightened Constitutional amendments receive a systematic kicking in the teeth every day of our lives in no way detracts from their brilliance. We love those ideas. Politicians love to make noble speeches about them. We love to write about them and sing about them and dwell upon them. We like to do almost everything except act consistently upon them.

This tendency toward "glittering generalities" has been just as apparent in the recent articles, speeches and pronunciamentos dealing with motion pictures. Consider, for instance, a recent eloquence from Eric Johnston: The screen must be free to portray faithfully, and explore intelligently, the whole realm of human knowledge and activity. It must be free from repression and it must be free from reprisal. It must be free from propaganda. Only a free screen truly reflects free institutions and the lives of free people. The screen must be as free as the free press free radio freedom of thought, action, expression and religion. Vest the screen with freedom's armor so it can truly battle for free people and institutions.

Now this is a splendid sentiment. It is a statement that perhaps only an American could make. It rings with idealism, liberalism, intellectual crusading and good will toward men. It has everything on its side, except a sound basis in fact. For Mr. Johnston seems to assume that this cinematic Nirvana already exists, and is to be found in the general vicinity of Hollywood, California.

Now this would be a wonderful thing, if it were so. For the motion picture is the world's most powerful medium of expression. If there is to be One World, or even Two Worlds which are able to reach a civilized understanding with each other, the American film could become one of its most persuasive ambassadors. If our screen were actually "free to portray faithfully and explore intelligently the whole realm of human knowledge and activity," we might experience a revelation as revolutionary as the discovery of atomic power.

Why has our screen failed to live up to the lofty principles prescribed for it by Mr. Johnston? The answer to that question must penetrate the surface red-white-and-blue cliches and drive deep into the sub-strata of American liberties. America holds out the promise of freedom of speech. It is a unique offer and not to be lightly dismissed or disregarded. But freedom of speech is not a free-pass-for-life on the Liberty Express. Freedom of speech is a privilege, a luxury which can be bought with only one kind of coin: courage. For millions of Americans, free speech is just a pretty sentiment to hear long-winded radio addresses about on the Fourth of July. And I am not thinking of the conventional examples now: the 12 million Negroes, the labor organizers in hostile territory, etc. I'm thinking of the subtle cases: The men who know they have to yes their boss to keep their jobs. The ones who accept the fact that they must write or speak a certain way to please the chief. The ones who resign themselves to doing a certain thing in a certain way if they want to be sure of making money.

Freedom of speech for these peopleand every one of us can probably think of hundreds of them among our acquaintances—has become a purely hypothetical question. They may wax very loud and angry if anyone dares make the claim that we do not enjoy complete freedom of speech in America; but they quiet down as soon as it is suggested that they use this precious gift in their own careers or businesses.

So freedom of speech is not stolen from them by the Francos, Perons and the Commissars. Their freedom goes by default, because they lack courage, the pride, the determination and all the other strengths of character necessary to fulfillment of this promise.

This may seem to have wandered a long way from a discussion of the movies and their place in a democratic society. But I believe our movies are a typical and perhaps spectacular example of our failure to use our opportunities.

As an old Nuggeteer, who once slipped on the judicial robes of The Dartmouth's contentious critic Moe R. Ayer, I still rerhember the dismal ratio of good pictures to bad. I remember how the term "That's Hollywood," came to stand for everything that was false and contrived and pretentious and wastefully lavish. Throughout the war, on both sides of the Atlantic, I saw how Service audiences hooted irritably or twitted good-naturedly nine out of ten of the Special Service movies that entertained them in a monotonous, this-is-better-than-nothing kind of way. And so far, the reconversion to peacetime movies seems to have produced even fewer outstanding films than during the war years, when at least we had Sahara, Gung Ho,Action in the North Atlantic, Guadalcanal Diary, Bataan, and a few more, to leaven the hundreds and hundreds of meretricious, formula-bound "war pictures" which brought the war down to a B-movie level and thus insulted millions of men and women joined in a serious effort that deserved either artistic interpretation or silent approval, but surely nothing in between.

It has been said many times, by Eric Johnston, by Will Hays and other spokesmen for the motion picture industry, that our films have been America's best advertisers, bringing American values and American virtues to a world-wide audience. Of course Hollywood has sent out some films which have accomplished this. But it would have been highly educational for Mr. Johnston to have sat in the chilly darkness of a wartime London theater and heard the bitter amusement of a bombwracked audience who saw one of our most successful war pictures for what it was a rose-tinted, penny-postcard view of war, a picture into which at least three million dollars had been poured, but not three minutes of genuine feeling. Our American films have not failed to entertain the world. Nor have they failed to enjoy substantial profits from world markets. But they have not yet succeeded in presenting a truthful, sober, adult picture of our people and our way of life.

With half a century of film production behind us, it may be time we began to investigate the causes of the intellectual delinquency that marks so many of our movies. The key factor, of course, is that motion pictures are an industry first, an art second, a social service third. Even major studio hierarchies are limited monarchies, subordinated to the policies of their Boards of Directors, whose main interest in motion pictures is their ability to return a profit of some sixty-five million a year. In order to assure their reigns, major studio heads must keep their financial losses to a minimum. The safest way to do this is to fall back on formulas which have already passed successfully the ordeal-bybox-office. Certain situations, certain locales, certain combinations of personalities are found to be flop-proof, or virtually so. Thus the element of creative uncertainty is removed as far as possible. What remains is the film we have all seen over and over again—what comes to the minds of all of us when we say we've just seen "another typical Hollywood movie."

The big companies who gear their programs to this kind of mass production efficiency are no more concerned with Mr. Johnston's freedom of speech than are the producers of cigarettes, chewing gum and other necessities of modern lfe. The producers, directors and scenarists who turn out these cellophane-wrapped products have voluntarily swapped their freedom for long-term contracts and six-figure security. But in the last fifteen years an increasing number of artists have been attracted to Hollywood, a few for better motives than their public would suspect. Writers like Robert Sherwood, Dudley Nichols, and many equally capable, if lesser known, saw in the motion picture the most complex and satisfying of all the arts—reaching a larger audience than the rest of them combined. These men, together with a handful of producers and directors, took a healthy, new attitude toward their profession. It was not merely an oil well whose prodigious profits were to be enjoyed, but a social responsibility, a powerful agency of public influence.

In a day like ours, when the American business man is still to be found at the pinnacle of our society, it is encouraging to find a talented minority who while hardly abjuring an interest in profits are sensitive to the need for broadening the boundaries and deepening the content of their films.

Some idea of the heights which can be reached is indicated by the great pre-war work of art, The Informer, directed by John Ford from a Dudley Nichols script; The Long Voyage Home, a Ford-Nichols film produced by our own Walter Wanger; Lewis Milestone's Of Mice And Men and A Walk in the Sun, searching films of American life like Fury, The Grapes ofWrath, The Ox-Bow Incident and, most recently, The Best Years of our Lives. All these are eloquent proof of Hollywood's creative vitality. It may be a small flame but it throws a surprisingly wide shaft. Exposed for two generations to the cold winds of commercialism, it refuses to be blown out.

There are even a few signs that would lead a congenital optimist like myself to believe that we may see this small flame fanned and fed in the coming years. Thirtyfive years ago there was a monopoly strangling motion picture progress. Satisfied with its profits, the Motion Picture Patents Company saw no reason why films should be extended beyond their ten-minute length or developed beyond their pie-inface comedies and penny-dreadful melodramas. But a group of rebellious independents—Goldwyn, Zukor, Lasky, Laemmele and others—wanted to push back the frontiers, pioneer with thirty-minute pictures, dramatize English classics, introduce acknowledged stage stars. Crude as their results seem today, they were a tremendous step forward in 1912.

In 1947 the cycle has been completed. The major studios' monopoly, through their block-booking system, is beginning to crumble. Many of the industry's outstanding creators Capra, Wyler, Stevens, Milestone are forming independent companies which will permit them more freedom than ever was possible in a big studio set-up. Other directors, producers and writers are being offered greater leeway within the old framework. Film costs are rising, purchasing powers diminishing. Film audiences are growing choosier. In the big cities there is new competition from high-grade British pictures and from Italian and French films which make most of ours look like shabby shoes deceptively polished to a bright sheen.

The time is ripe for a Hollywood renaissance. Perhaps films like The BestYears, Boomerang and The Yearling are a beginning. Perhaps, like great Hollywood films of the past, they are merely shooting stars. Let us hope not. And let us do more than hope. For it is both the strength and the weakness of the motion picture that it is the most democratic of all the arts. Our faith in the people, in the long run, is tempered by the evidence that The LongVoyage Home and The Ox-Bow Incident fell by the wayside while Coney Island and Hollywood Canteen zoomed to astronomical profits. The film-makers are not the only ones who abuse or neglect their freedom of speech. American film audiences, by their repeated failure to respond to more challenging, less stereotyped pictures, forfeit an exciting role—an opportunity to participate in the extension of freedom of speech to the greatest of all dramatic mediums.

A practical way to combat this negligence on a local level would be to organize a film society at Dartmouth like those which are taking root in England and France. In public school I was subjected to courses in music and art appreciation. It is time we had courses in motion picture appreciation as well.

Jean Benoit-Levy, grand old man of French cinema, now head of the United Nations film project, in his recent book, The Art of the Motion Picture, discusses the artistic and social responsibility of film producers toward an art "whose great aim, as in fact that of all arts, is to elevate the thoughts of men. I would like to express my faith," he concludes, "in the destinies of the art of the motion picture, provided those who serve it are ever conscious of the greatness of its mission."

Hollywood may yet meet that challenge, may yet redeem its promise.

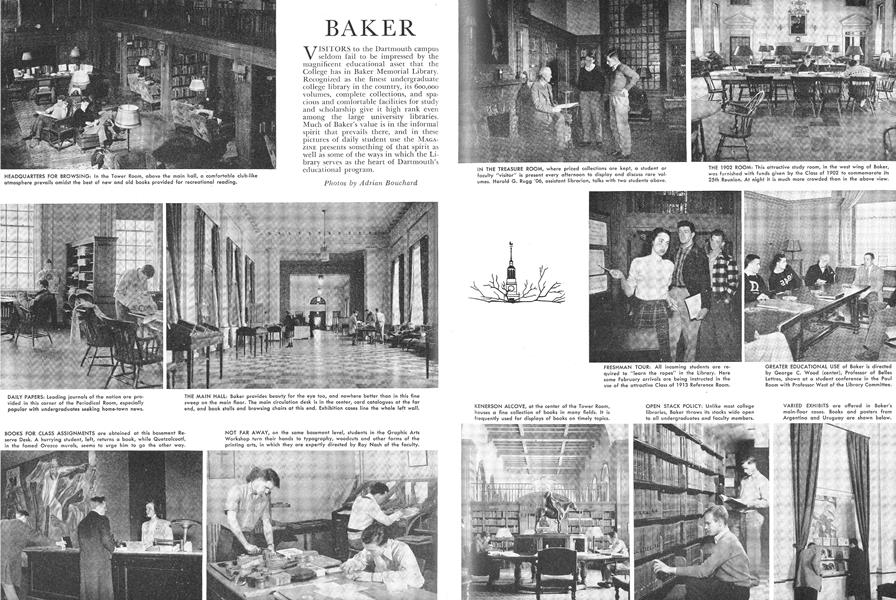

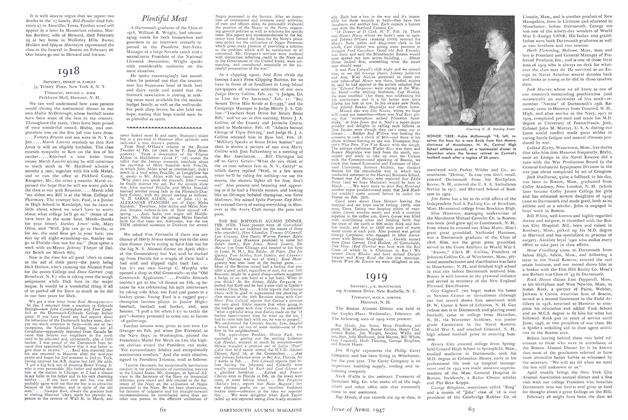

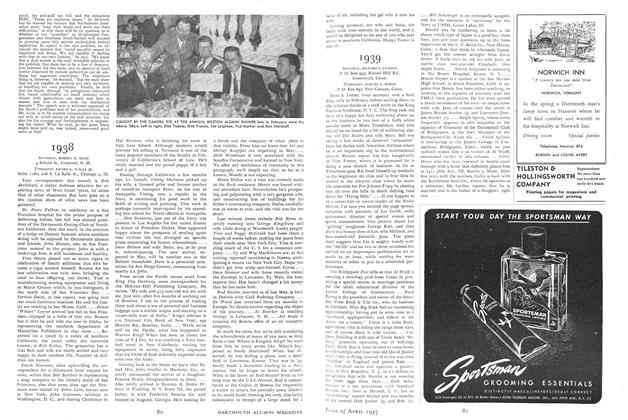

ON THE SET IN HOLLYWOOD: Budd Schulberg '36 (left), author of this article, shown with Ted Baehr '29 (center), known on the screen and stage as Robert Allen, and with Dean Herluf Olsen '22 of Tuck School, then visiting California. The picture was taken before the war, during the filming of "Winter Carnival."

Budd Schulberg '36 began his association with Hollywood at the tender age of five when his family moved from New York to California. As the son of B. P. Schulberg, well-known producer, he was in a position to learn a great deal about the movies and did. Later, after graduating from Dartmouth, he wrote the rather sensational best-seller, What Makes Sammy Run?, in which he dissected, in the character of Sammy Click, a certain Hollywood back-stabbing type. At Dartmouth, Schulberg was an honors student in sociology and editorin-chief of The Dartmouth, in which role he gave Hanover a lively year. After graduating he returned to California as a writer for Selznick and RKO. He again came East and settled down in Norwich, Vermont, to write Sammy, which appeared in 1941; and although his father reputedly advised him not to come back to Hollywood after that, he eventually resumed his writing there with Columbia and RKO until he enlisted in the Naval Reserve. During the war he was a Navy lieutenant attached to the 0.5.5., and his was the important assignment of gathering together and editing the seven-hour-long atrocity film which was shown as evidence against the Nazi leaders at the Nuremberg trials. Since his discharge from service he and his family have been living on a farm in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, where he has just finished a new novel about a prizefighter.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleFreedom of the Screen

April 1947 By WALTER WANGER '15 -

Article

ArticleCharles Edward Hovey '52

April 1947 By ALLAN MACDONALD -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

April 1947 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

April 1947 By Charles Clucas '44 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917

April 1947 By MOTT D. BROWN, DONALD BROOKS -

Class Notes

Class Notes1937

April 1947 By JOHN H. DEVLIN, ARTHUR H. RUGGLES JR.