lASTIAST October, Dartmouth's student government disj covered a paradox. Analyzing the Constitution for an undergraduate government prepared by the Committee on Social Organizations, the student body concluded that if it was a Constitution, it did not provide for a government. Complete self-government, it was apparent, was impossible, so although the Constitution was quickly and efficiently approved, the only signs of interest came from its critics.

Now, eight months after its unveiling, the paradox of a Constitution without a government remains. But Dartmouth has an Undergraduate Council, and the critics have disappeared.

in the intervening period, conceptions have changed and with them the Constitution. Taking cognizance of the critics' vigorous and by no means irrational uproar, President Dickey in December appointed an eight-man committee of students to hear complaints and suggest revisions. Starting in almost complete ignorance, the committee spent five months hearing representatives of every campus group, organized and unorganized, and drafting a revised edition of the original document. Realizing that self-government might never be perfect, the committee determined nevertheless that at least it should have as few discernible flaws as possible.

The result of their labors was a document streamlined and simplified, including two significant changes. Membership on the Council is reduced from 106 to a maximum of 50, and freedom of press and speech is guaranteed.

For the majority of the earlier critics, the reduced membership is the most important revision. The original Constitution had conceived of a large Undergraduate Council which would serve as a student forum, town meeting style, and as a reservoir from which to select executive committees, including Palaeopitus. The original framers had erred, claimed the critics, in forgetting that size does not mean representation and usually petrifies into legislative inertia. Team captains, fraternity presidents and dormitory chairmen were legitimate members of a representative body, but not all at the same time. So the Council was lopped in half, and authorized to meet more often than the one session required to select a Palaeopitus. And of the fifty members, sixteen are now elected directly from the classes and up to eight may be added by the Council itself from the student body at large.

The new Constitution still does not provide for complete self-government, but out of the document approved by President Dickey last April may yet grow an effective organ of undergraduate accomplishment. For a Constitution is a deceptive thing. It deals in generalities, in definitions, in methodology. But out of the dry lingo of its generalities and its definitions will develop the procedures, the policies and the solid achievements that years hence may reach into every corner of College life.

A few needs it could fulfill are already clearly apparent. A course survey such as the one undertaken by TheDartmouth would carry more weight if executed under the aegis of the entire student body through its representatives. Difficulties in everything from Mrs. Hayward's breakfast hours to seating at football games and two-semester language requirements could be aired in the Undergraduate Council and, by the sheer pressure of fifty raised and respected voices, eased or corrected. The lack of student interest in extracurricular activities might be more effectively attacked by a Council of extracurricular leaders acting in concert, rather than by the newspaper alone. And, incidentally, student government provoking, willy-nilly, greater interest in undergraduate affairs, might by its mere presence stimulate interest in allied undergraduate organizations.

There remain two pitfalls. Student government could easily deteriorate into a bandwagon for campus crackpots, into just another memorial to good will in theory but inertia in practice. The first Council will have two strikes against it: a lack of student knowledge and only partially aroused student interest. If the first Councils abuse their potency, if their actions are mainly verbal, if they fall into disrespect, government at Dartmouth may become an unredeemable carcass. Undergraduate interest, the respect for an effective tradition, will not grow spontaneously. The student body, on the contrary, is more like a man from Missouri than the remarkable Topsy. And the only way to show them will be by effective and intelligent action.

Unfortunately, since this cannot be complete self-government, action of the Council must be matched by Administration action. And this is the other pitfall. It will be too easy for the faculty to dismiss a Council request for re-evaluating language requirements, for example, as the howling of unknowing children. On the vital issues, it would be natural for the Administration to turn its back before it got stung.

It is up to the Council, then, to prove by intelligent consideration that it does not represent unknowing children. And it is up to the Council and the Administration together to prove to all Dartmouth men that self-government need not be complete to be useful.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleA RIVER CAMPUS?

June 1947 By PETER E. COSTICH '47 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1919

June 1947 By J. K. HUNTINGTON, MAX A. NORTON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

June 1947 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921

June 1947 By DONALD C. MIX, ROBERT M. MACDONALD -

Article

ArticleTHE TIRED VETERAN

June 1947 By EDWARD F. EUBANKS '44 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1943

June 1947 By FRED F. STOCKWELL, WILLIAM T. MAECK

HOWARD D. SAMUEL '46

Article

-

Article

ArticleNEW QUARTERS SOUGHT BY THE GRADUATE CLUB

NOVEMBER, 1926 -

Article

ArticleTHE DARTMOUTH PICTORIAL

November, 1930 -

Article

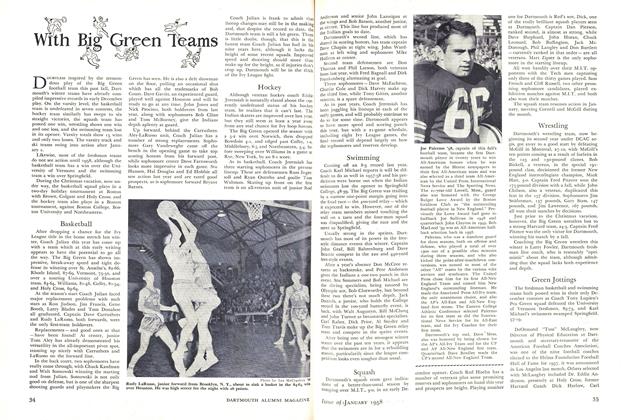

ArticleWrestling

January 1958 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Article

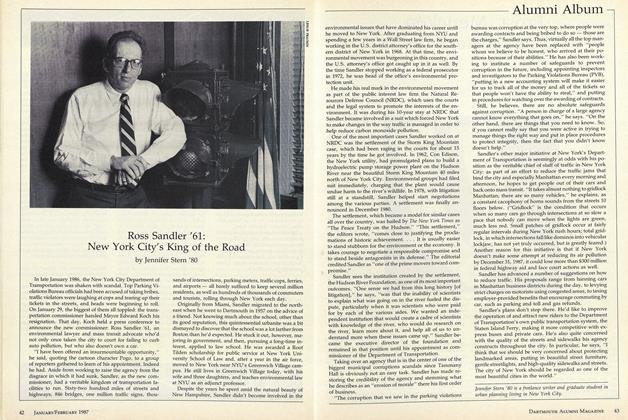

ArticleRoss Sandler '61: New York City's King of the Road

JANUARY/FEBRUARY • 1987 By Jennifer Stern '80 -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH SKI SCHOOL

February 1946 By STEPHEN J. BRADLEY '39 -

Article

ArticleThayer School

February 1955 By WILLIAM P. KIMBALL '29