Dartmouth Senior, Who Served as Naval Officer, Scores General Apathy of Students and Their Preference for Courses that Lead to "Security"

SINCE THE END of the war, when they started pouring back into the col- leges and universities, student-veter- ans have come in for a great deal of praise. To a nation of people who regard educa- tion as their main hope, the veterans' im- mediate response to the educational fea- tures of the G.I. Bill was gratifying. The even more gratifying first reports of the high quality of the student-veterans' work allayed any fears that government support would lead to loafing and irresponsibility.

It was apparent at Dartmouth when the first sizable group of returned veterans made a general grade average of 2.63 (compared with the normal peacetime average of 2.3) that, among the veterans, it was no longer gentlemanly to settle for a C. Men were trying for A's and admitting it. The hope that returning veterans would take their college work seriously was soon realized; but now, almost two years later, it is evident that a good many predictions, made at the end of the war about veterans returning to Dartmouth, were wrong guesses.

One of the most disappointing of the wrong guesses, to many Dartmouth alumni, was made about returning athletes. "We expected them to be real fighters," said Bill McCarter, "as were the veterans who came back to college after the first war. But that was a short war. The boys weren't away long and they were still of college age when they came back." Unlike most Dartmouth activities, the varsity teams are not suffering from a lack of participants. The students turn out in great numbers, but few of them are good athletes. According to Mr. McCarter, "They haven't got that old college try." He added that he does not expect Dartmouth sports to rise to their normal level until most of the veterans are gone.

Among the unrealized hopes were those held by people connected with the College's extra-curricular organizations. The editors of the Jack-o-Lantern have been handicapped by a shortage of help, and several times during the fall semester the editor of The Dartmouth had to act as his own night editor because no one else was available for the job. The paper published an editorial decrying the lack of student interest in extra-curricular activities, and, for months, ran advertisements urging men to participate in them.

Warner Bentley has found most of the veterans in The Players more mature and efficient than pre-war students, but fewer students have turned out than in former years, and many who have come out have quit, for various reasons, after a few weeks.

Bill McCarter has had difficulty getting managers for his teams. This year many of his men have had to manage several teams, and have been handicapped by overwork and lack of experience. At present he has sixteen freshman managers to fill nineteen positions, and between the freshmen and the upperclass managers, an entire class is missing.

According to John Rand, the trouble in the Outing Club is a result of having "too many officers and not enough enlisted men." The Outing Club has not suffered from a decrease in total personnel. It has close to nine hundred members, as compared with a normal membership of four to five hundred. More people are using the cabins and shelters than before the war. The difficulty comes in getting men to do the menial work of clearing ski slopes, cutting fire wood, digging latrines and garbage pits. During Winter Carnival Week, the leaders of the DOC were unable to convince the general student body that Carnival is a College event, and that the DOC needed a lot of help to put it over.

It is too early at this writing to tell what will happen this year, but last spring, when the first postwar Green Key dance was held, it is reported that three students decorated the gym, and that two of the three were not members of Green Key.

A number of explanations can be given for the present lack of interest in extracurricular activities. The common one, and the most obvious if the veterans' high grades are considered, is that the veterans, more mature than pre-war college students, have definite goals. They do not need outside activities and they haven't time for them. They came back to Dartmouth for education and they're serious about getting it. That statement might be made truer by a substitution of the word training for education.

It is difficult to say anything specific that will apply to all 2300 veterans at Dartmouth, but a look at the courses they are studying should give an indication of general aims. Since the war there has been a proportional increase in the number of men taking commercial courses. The big emphasis is on economics; and psychology, especially industrial psychology, is enjoying a boom. According to Prof. William A. Carter, head of the Department of Economics, the number of men majoring in economics is about 50 per cent higher than before the war. Dean Olsen of Tuck School has reported increases of 44 per cent in enrollment in the first-year class at Tuck School and 150 per cent in the second-year class.

Foreign languages, philosophy, art, English, science and the other non-commercial subjects are not drawing as large a proportion of students as they did before the war. The prediction, and hope of many, that men would come back from the war with a greater realization of the value of the humanities, and a desire to study them, was one of the wrong guesses.

Many of the student-veterans feel very acutely the pressure of time. Few of them would say that time spent in the armed forces was time completely lost, but there is a general feeling on the campus that it is late in the game. This feeling of timepressure is evident in the lack of participation in extra-curricular activities and in the hard work that is being done, as indicated by high grades.

But high marks can indicate little more than hard work and an ability to study and to write examinations. What the veterans' grades do not indicate is the cynical attitude that is unmistakably present at Dartmouth. Emphasis on courses that pay off could be an indication of cynicism, but, since most of those courses come under the general heading of Social Science, it could also be taken as evidence of an increased interest in the social, economic and political problems of modern society. It is undoubtedly true that some of the veterans have returned to Dartmouth with a desire to increase their understanding of social problems, but it appears that those men are in the minority. The general desire, understandably enough, is to do well in courses that provide a background with a high market value.

Classroom discussion and Coffee Shop conversations often indicate more in the way of attitudes and aims than do grades. The most noticeable thing about classroom discussions is the almost total absence of them, even in courses where student opinion is requested by the instructor. In many classes the most frequent questions asked relate to notetaking word spellings, dates, names, or statistics dictated too rapidly. There is a paucity of questions or statements indicative of a desire for real understanding. One professor recently remarked that students often stop after class to talk with him, but seldom to discuss the lecture material. All they want usually is a repetition of facts for their notes or information concerning what parts of the lecture they will have to remember to pass the next hour-examination.

Classroom questions not related to factual notebook material, are often merely attempts to "catch" the instructor interrogative refutations that are the product, not of critical thinking, but of a resistance to any kind of authority. It's the Armyengendered attitude of "not takin' nothin' off nobody."

Intellectual apathy, manifested in-a lack of effort toward genuine understanding, is not limited to men preparing themselves for the "Big Money." Recently an instructor of a class studying American poetry quoted Edwin Arlington Robinson as saying, ironically, "I'm the damnedest optimist that ever lived." Two days later, a guest instructor, lecturing to that class, made a reference to "Robinson's pessimism." Immediately, a student, who had apparently written in his notes on the previous lecture, "Robinson—optimist," demanded to know who was right—the regular instructor or the guest lecturer. When the visitor tried to explain that both words were useful in discussing Robinson, but that neither was an adequate label for the poet, several other students took up the cry, demanding that the instructors decide in favor of one of the words.

During that same lecture on Robinson, a student complained half-way through the class period, that the lecturer had given him only three lines of facts for his notebook, and that he was afraid, if the lecturer did not given him some more concrete information, he would not have enough material to pass the examination scheduled for the next class period.

Another wrong guess was the prediction at the end of the war that returning veterans would be politically active and extremely aware of national and international problems. "Poor old Harry" and "that damned Lewis" are remarks indicative of the depths of profundity reached in Coffee Shop political conversations. The American Veterans' Committee, the only veterans' organization on the campus, rarely attracts over twenty-five men to its meetings. Since AVC is admittedly a politically progressive organization, the small attendance at its meetings might indicate that Dartmouth students are overwhelmingly conservative in politics. But the absence of a conservative political organization, the infrequency of political discus sions, and the lack of interest in current issues, are evidence, not of political conservatism, but of apathy.

This dearth of interest in social, political and economic problems is not limited to the large group of uninformed students that is always present on a college campus. It is probably the strongest manifestation of the general apathy that pervades Dartmouth.

It is hoped that the Great Issues course to be instituted next fall will, for one thing, foster an interest in current social problems. If the present inertia can be overcome through the Great Issues course, there is a chance that an intellectual curiosity and interest necessary for attaining an understanding more profound than that required for passing examinations with high marks will become the predominant postwar spirit at Dartmouth. The more pessimistic members of the faculty will be surprised if the current apathy is broken before most of the student-veterans graduate.

Two years after the war, a repetition of the Roaring Twenties has not occurred, nor does it appear likely that a gay recklessness will become the dominant attitude in the next couple of years. Drinking at Dartmouth seems to be heavier than it was in pre-war years. But the drinking is not being done in the spirit of reckless abandon that was characteristic of the Twenties. Dartmouth students today are not rebellious. They have litle to rebel against. They do not, for example, have prohibition or the strict social conventions to flaunt that their fathers had. And they are not carefree, but serious. Unlike the young men of the Twenties, they are looking, not for a good time, but for security.

With the desire for security becoming the dominant human drive, not only in America, but all over the world, it is not surprising that it should be the motivating force in students who have returned from fighting in the most destructive war in history.

But the desire for security, in the narrow sense, is not making searching, critical students of Dartmouth's veterans. If anything, it is causing them to view education as merely vocational training, and high grades and a Dartmouth degree as good, secure talking points in future interviews with prospective employers. It is causing men to take short-cuts, to hole-up with the "facts" and to shy away from the distressingly confusing problems of life that students should at least learn to recognize in a liberal arts college—the problems that have no notebook answers but many possible personal answers, the problems that can never be solved by textbook formulas but which, if dealt with honestly and searchingly, offer a chance for a greater sense of personal security than money in the bank and' freedom from debt can ever afford. It is doubtful whether many of Dartmouth's security-conscious veterans have even asked themselves the basic questions about security.

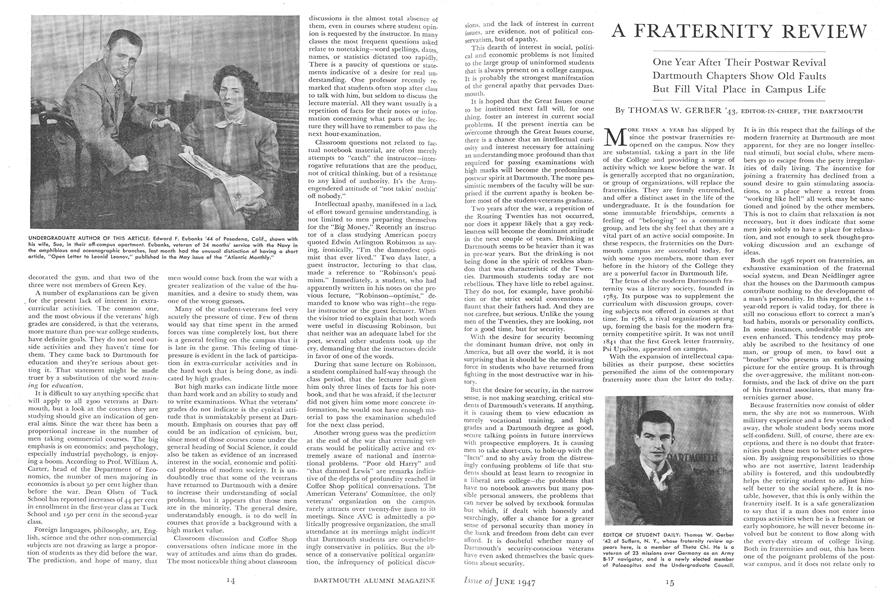

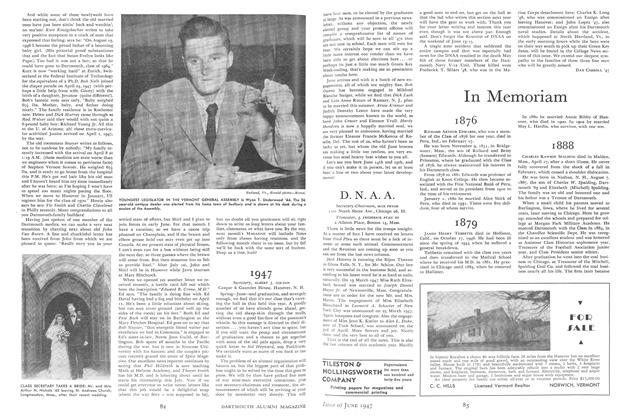

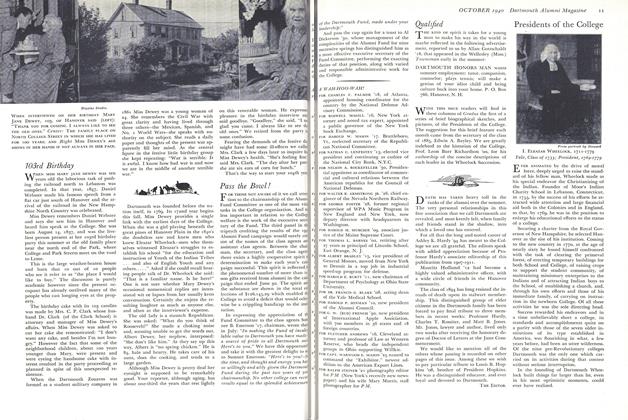

UNDERGRADUATE AUTHOR OF THIS ARTICLE: Edward F. Eubanks '44 of Pasadena, Calif., shown with his wife. Sue, in their off-campus apartment. Eubanks, veteran of 34 months' service with the Navy in the amphibious and oceanographic branches, last month had the unusual distinction of having a short article, "Open Letter to Leonid Leonov," published in the May issue of the "Atlantic Monthly."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleA RIVER CAMPUS?

June 1947 By PETER E. COSTICH '47 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1919

June 1947 By J. K. HUNTINGTON, MAX A. NORTON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

June 1947 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921

June 1947 By DONALD C. MIX, ROBERT M. MACDONALD -

Class Notes

Class Notes1943

June 1947 By FRED F. STOCKWELL, WILLIAM T. MAECK -

Article

ArticleFACULTY HELMSMAN

June 1947 By JOHN P. STEARNS '49

Article

-

Article

ArticleWins Pulitzer Prize

June 1935 -

Article

ArticleSocial Survey

June 1935 -

Article

ArticleReynolds Grants Open To Recent Graduates

NOVEMBER 1964 -

Article

ArticleYour Football Tickets—An Explanation

OCTOBER 1931 By Dean Chamberlin -

Article

ArticleNo: Trade Not "Free"

Jan/Feb 2006 By Gary Weissman '02 -

Article

ArticlePass the Bowl!

October 1940 By The Editor