Former Special Assistant to the Secretary of State, in Great Issues Lecture, Sees World Union as Only Check to Total War Which Would Destroy Society

GENTLEMEN, IT'S PRETTY DISCOURAGING, I suppose, to start with a definition, but if you don't mind I'd like to do so this evening. After all, it would do no harm to know what we are talking about. That isn't as bad as starting off as some speakers do by saying "I have 16 points. I'll now take up number 1."

Let me try to define what I mean by world government.

There are two concepts of world government. The first is what we might call "the full world government," that is, the kind of government which exists, for example, in France where all the powers of the state are -centered in the government at Paris, and where the delegation of the responsibility for government to the Departments is made at the discretion of the central government. This central government, leaving questions of philosophy aside, has all the power of the State in it. There is no limit as to what it may do except insofar as there may be some specific restrictions in the constitution. For practical purposes, the power of this kind of government is complete.

Now many people when they talk of world government talk about an organization which would have such total and complete power. For example, the world government that is envisaged by Dr. Adler, Dr. Borghese and those others of the Chicago group who have recently issued a form of world constitution, is this kind of full world government.

There is, however, another kind of world government which is a limited world government, the powers of which are very fully restricted. Such a government might be called "federalist or limited," because it has only limited authority over specific fields. An example of this is, in the early days, our own United States Government. You will remember that in 1787 the states still had a great measure of jealousy about their individual rights, and they were willing to grant to the central, or federal, government only certain specific powers. Since then, by interpretation of the Supreme Court and by amendments to the Constitution, the powers of the government of the United States have so increased that there is practically no difference between the federal government in Washington and a full government such as exists in France, Great Britain, and most other places. But when I am speaking of a limited world government I am speaking of one whose authority is even more restricted than that of our federal government in 1787.

Specifically I am thinking of the United Nations Organization with its Charter so amended as to have the power to enforce laws for the regulation of armaments and against aggression. Only in that restricted field would the limited world government of which I am speaking have authority. So let us, even at the cost of some repetition, get these two ideas very clearly in our minds.

When you talk of world government you must first find out whether you are talking of a full world government which would have powers over armaments, over international commerce, over tariffs, over immigration and emigration, and would have a police power to enforce a general criminal code, or whether you are speaking of this extremely limited form of world government about which I will speak more in detail later.

Let me say at the outset that, in my opinion, any idea of a full world government within the visible future is completely unrealistic. I believe that the idea of a full world government is entertained only by theorists with no sense of political realities today, or is sometimes used by malicious people who wish to discredit the whole idea of progress in international relations and put up this full world government as a straw man which it is easy to destroy. On the other hand, I believe that the limited world government of which I have spoken is something which is entirely feasible within the very immediate future, specifically within the next few years, and more specifically, before the happening of another great war.

I further believe, if you will allow me to state my conclusion first, that unless the United States takes the leadership to convert the United Nations Organization into a limited world government within a very short span of time a world war is inevitable, a world war which, whichever side wins it, will mean the destruction of all sides. You will forgive my partisanship on this issue when I say that this is the great issue, in practical terms, which faces American men and women today. The issue is truly the question, in my opinion, of the survival of this country.

Now this is all very closely bound up to United States foreign policy. As I see it, the fundamental purpose of the United States foreign policy is to achieve peace. We are going about it in three ways, and I think that thia is fairly generally recognized among the men in government in Washington. We are pursuing one lane of our foreign policy on the economic front. We realize that nothing can be done unless the peoples of Western Europe, indeed of all of Europe and of Asia, can get their minds off the question of their survival and can get enough to eat and can get their business going so that they may have the material things of life. On this front, in my opinion, the government of the United States is acting with great foresight and great wisdom. The Marshall Plan is the core of this economic attack upon the problem of peace.

A second front on which we must pursue the question of peace is the question of being strong. We must be strong in two ways: We must be strong in our own domestic justice, and our own domestic economy, and we must also be strong in the military sense. Because until we can achieve a political solution for the world it is obvious that war will continue to be the ultimate way of solving differences between nations. It is obvious that we are living in a world of power politics, and that if the United States is to play its part in that world it must be strong. Therefore, until we can achieve our political solution, we must have a strong military establishment. This military establishment must not be regarded as being in competition with our economic policy: In particular, our program for the placing of our military establishment must not be used as a device to cut down on Marshall Plan aid. On the contrary, these two things are interdependent and complementary. Western Europe, in particular France and Italy, will not stay on the western side unless they are aided in both regards, unless they get economic aid from the United States, and unless they know also that this is the United States which, in this hurly-burly of world chaos in which we exist, is not going to be pushed around. They want strength from us as well as material help.

But none of these things, gentlemen, will achieve our objective of peace; neither a strong military policy nor a strong economic policy will produce peace. Nothing will produce peace except a political solution of the affairs of the world. The reason for that is, I believe, that war has now become an unbearable institution. I give you as an example of that the situation in Germany. We are afraid to withdraw our troops from Germany, and rightly so at this moment; we are afraid and do not want to sign a treaty of peace with Germany because we know that the signing of such a peace will involve the withdrawal of our troops from Germany. And if we do withdraw our troops from Germany, Germany will be left alone either to fall under Soviet domination or again to become a menace on her own account. The same thing is true in Japan. We do not want to sign a peace treaty with Japan and withdraw our troops, again for the same reason. The only places where we have been willing to sign peace treaties have been in the lesser Balkan states and with Italy, and there we signed the treaties only because we thought that those countries were not especially significant and we were in a position to take a chance.

Now let us have a look for the moment at this proposition that war is now an institution that we tan no longer permit to exist in the world. For that is the basis for my conclusion that we must have limited world government within the very immediate future. If we look at this thing from a long point of view; if, for example, we take the view of history which is so ably put forward by Arnold Toynbee in one of the great history books of all time, A Study ofHistory, you will find that, on analogy, we are now in a time immediately preceding disaster. You will remember that Toynbee points out that every society goes through a certain rhythm. It starts off its existence and then it runs into a time of troubles when there are wars between the states which compose the society. Then the society recovers from its time of troubles and goes through a fairly peaceful period. Then again for the second time it runs into a time of troubles and that second time is more violent than the first. And out of it comes a universal state. And that state, being based on wrong things, being based on domination by force, collapses and the society disintegrates into chaos. An example of that is what he calls the Hellenic Society, which is really the Greco-Roman. It had its first time of troubles at the time of the wars between Athens and Sparta; then it had a lull after that; then came a new time of troubles during the Carthaginian Wars; and finally came the universal state which was Rome and the Roman Peace, which soon collapsed and was over-run by the barbarians.

When Toynbee looks at our own Western Society, he says that it started about 800 A.D., then ran into a time of troubles which, roughly speaking, began about the time of the religious wars in the 17th century and continued on up to the climax of the Napoleonic Wars; then was followed by a lull in the form of its peace of the 19th century up to 1870, when the second time of troubles began. Toynbee's analogy is, of course, that out of this will come a universal state; but it will be a universal state resulting from a battle between the two giants; it will be an indecent universal state which has been founded on violence, and it will collapse.

Now, somebody once said "beware of historical analogies because they are nearly always right." But let us pass the historical analogy and inquire why it is that war is now an institution that this country can no longer tolerate. Certainly you will agree that since the birth of the German Empire in 1870, war has come on at a crescendo. The trouble started, I suppose, as far back as the en masse, the total conscription of the French Revolution, which changed the kind of wars which had been fought up to that time (which had been more or less polite wars with few people engaged on either side and, generally speaking, except for cases like the religious wars, without the total devastation of the entire country). Once the idea of the nation in arms was born, and was applied in World Wars I and 11, war became such that it was almost sure, unless stopped, to destroy the society in which it took place. But even worse than that is the revolution in applied science through which we are now going.

I have spent the past six months in careful study with the military authorities of the country of our military situation, and I have learned a great deal about the nature of modern war and of the trends in the development of weapons which is now taking place. In the recent Report of the Air Policy Commission to the President, the Commission reached the conclusion that it was not safe to count on other nations not having atomic bombs in quantity by January 1, 1953. We noted also that bacteriological weapons, which are comparable in their destructive power to atomic weapons, are now being studied carefully by all other nations and that the means, of course, of distributing these bacteriological, or biological, weapons is already available. It is a relatively simple matter for enemy agents to distribute these very violent biological weapons by locating them in the city subways, by placing them among our crops and herds. The biological weapon is a terrible thing.

And, of course, that is not the only thing that is going on. It doesn't do an enemy any good to have these weapons unless he can deliver them. And so the Air Commission made a careful study of the means of delivery of weapons in direct attack upon the United States. We reached the conclusion that the current development of airplanes with long range and flying at speeds near that of sound was something that would have to be envisaged within the next five to ten years. The guided missile problejn, about which you have heard so much—that is to say, the supersonic, transoceanic guided missile which is capable of flights of g,ooo miles or more, with an accuracy sufficient to hit a city—is something which is generally regarded as being for a further period in the future: the general estimate is from 10 to 25 years. The subsonic guided missile, however, was estimated in open hearings before our Commission as being an entirely feasible thing within five years. By that I mean subsonic missiles of the V-i type, capable of a 5,000-mile range and of accuracy sufficient to strike a city. I simply cite those facts to show that the rate of destruction which is now being prepared by man is so terrible that any war in which we will become engaged in the future is one which neither side can win.

I have cited these facts merely to justify my argument—and I don't know why you have to justify it—that war is an institution which is no longer bearable. And that brings us to the question as to how we are going to get rid of it. That leads me to the conclusion that I stated at the beginning: that the only possible way of getting rid of it is by what I have called limited world government.

Now, let me be a little bit specific about this. If you can bear with one minute or two more of history, I would like to point out that this idea of establishing a rule of law in order to control the weapons of destruction is nothing new. I will not go back beyond the recent peace settlements, the settlements which took place after the Napoleonic Wars and after World Wars I and 11. About a year ago I made a somewhat superficial study of these settlements, and I-was struck with one thing, and that is that they fall into almost identical patterns. Each one of these settlements has this in common: they were settlements by coalitions, that is, defensive coalitions which had been attacked by would-be world aggressors. In each instance the defensive coalition had won.

There were two characteristics of all three settlements: one was that the victorious coalition sought to set up once more the status quo which had existed before the war. That was the thing which had been disturbed and that was the thing to which they wanted to go back. In all three cases they have failed in that, and we are not concerned in that phase of the settlement.

But what is of interest to us is that in each one of these three settlements the victorious coalition tried to set up some scheme whereby it could guarantee that war would not happen again. They had been attacked, their affairs had been disrupted by a war, they didn't like it, their memories were keen as to the horrors of the war and they did some very daring things to try to stop future wars.

Now these attempts to create a peaceful world divide in all three settlements into three clear phases. The first phase is what you might call big power solidarity, in which the cohesion that existed during the war when the Allies were fighting together is carried over into the peace. That first phase lasts but a very brief period. During the Congress of Vienna, as you remember, the Allies very nearly went to war. You remember the disputes which Wilson had at the Conference at Versailles, and you remember that the United States soon broke up any solidarity that might have existed by refusing to join the League of Nations. And you may remember that at the San Francisco Conference, Mr. Stettinius, who was then Secretary of State, did something in connection with Argentina which was regarded by the press as being anti-Soviet and was roundly denounced from coast to coast. At that time Big Three solidarity reigned supreme. It collapsed, however, almost utterly at the Moscow Conference in December of the very same year, and you can see from the recent spectacles in the United Nations Security Council and General Assembly how much of that is left at the present time. So the big power solidarity, the hope that the nations would be able to continue in peace the solidarity they had in war, failed in all three settlements.

But the nations do not give up with these defeats. In each one of these three peace settlements they have desperately tried to find some substitute, some institutional substitute, for this solidarity which has collapsed. And nearly always it has centered on armaments. For example, after the Congress of Vienna, the three Continental allies made a proposal to Britain to establish an international army at Brussels under the Duke of Wellington and an international navy with headquarters in Africa under a British admiral to enforce the peace. The plan was rejected by the British because they said that they didn't go in for international armies and, besides, no one parliament could commit the next parliament. That ended that.

But the same thing happened after the first world war and was even more dramatic. The French insisted time and again duripg the Paris Peace Conference on having an international police force. Later they insisted that the very broad disarmament provisions of the treaty of Versailles should be enforced. They wanted to set up a rule of enforceable law. They wanted to give to the League of Nations a police force which would be stronger than that of any nation state or any combination of nation states, because only in that way, said the French, would it be possible for the League of Nations to enforce the peace. The phrase was a League of Nations with teeth in it. It was the Americans and the British who rejected this idea. But the French fought on. And a very curious and dramatic thing happened in 1925 when the Labour Party then in power in Britain, working with the French, nearly put over the Geneva Protocol which would have done just these things—eliminated what corresponds to our modern veto in the Security Council and provided for a police force and a disarmament of the nation states which would have had the practical effect of making out of the League of Nations a government of very limited power, but nevertheless with powers sufficient to enforce the peace. Seventeen states signed the Geneva Protocol. It was always referred to as the high-water mark of the League. But just at that moment the Labour Party fell, the Conservative Party came into power in Britain, and the Geneva Protocol was rejected and never came to life again. And then the third phase started.

This third phase shows a deadly parallel with what is happening now. Once the League reached the highwater mark of the Geneva Protocol and failed, it died. Only lip service was paid to it. It had gone up to the verge of becoming a limited world government, it had failed, and from then on the big powers made all of their arrangements outside of the League.

Now, let us look at what we are doing at the present time and see how exactly that same parallel applies in. the peace settlement after World War 11. The parallel is really depressing. I have already referred to the collapse of big power solidarity. We also, once that had failed, moved into a second phase, which, if you will allow me, I will go through very rapidly. The first part of that phase was the Atomic Declaration of November, 1945. You will remember that the atomic bomb fell after the San Francisco Conference, and in November of that same year, 1945, President Truman, Prime Minister Attlee, and Prime Minister King, of Canada, signed the Atomic Declaration in which they said two things. They said (i) the nations must give up the atomic weapon and all other weapons of mass destruction and (s) they must give it up, however, only upon the establishment of a fool-proof system of security. The exact words that they used were not those. They said something about "adequate safeguards to protect complying states against the hazards of violations and evasions." But what was meant was this, that nobody was going to give up the atomic bomb or any other comparable weapon unless something was done to see to it that the promise of other nations to do likewise could be enforced. And then the Atomic Declaration Went on and used words which, if they mean anything, mean a limited world government. They said that a foolproof system of security, or that long phrase about the protection of complying states against hazards and so forth, could be achieved only by die establishment of a rule of law, and by the elimination of the institution of war itself.

Things moved very rapidly. There is no doubt about it that during the early phase, immediately following the war, great things can be done. There is a dynamism in the air, a desire of the peoples for peace, which, incidentally, declines very rapidly, but nevertheless while it exists is capable of great things. Immediately following the Atomic Declaration there was the Moscow Conference of December, 1945, in which Russia approved of the Atomic Declaration, word for word without a single change. The matter then went to the United Nations General Assembly, and there in January, 1946, the General Assembly adopted the language of the Moscow Declaration, word for word, and provided for the establishment of the Atomic Energy Commission. Those words were a bit of a misnomer, although they were the words which were used. It really called for a commission to carry out this general disarmament program of atomic and all other comparable weapons of mass destruction.

From then on the history is confused. The Secretary of State appointed a committee which produced the Acheson-Lilienthal Report, which as you know, established a mechanism for the control of atomic weapons. But it had only gotten started on this work when Mr. Baruch was appointed to be the United States representative on the Atomic Energy Commission. The Acheson-Lilienthal Report did not go into the question of how we were going to see to it that a fool-proof system of security was to be established.

It was there that Mr. Baruch stepped in with the July 14, 1946 speech which is the counterpart of the Geneva Protocol. It is the high-water mark, so far, of the United Nations. The speech of Mr. Baruch on July 14. 1946 carried with it the hopes of mankind. There is no doubt about it that what he said in that speech was that he adopted the Acheson-Lilienthal Report as far as it went, but only on the condition that the United Nations be given the power to enforce the rule of law to eliminate war. He was not specific about this. He said it in generalities but he said it about ten times in the speech and there is no doubt about it that those who saw the promise of establishing a rule of law whereby disarmament and the outlawing of war would be enforced under a foolproof scheme were justified in their optimism. But then an unfortunate thing happened, it was exactly the thing that happened after the Geneva Protocol. It wasn't a shift in political parties, it was the complete abandonment of the idea.

Why it was that the fair promises of the July 14 speech were never realized I do not know. The fact remains that ever since the idea of fortifying the UN as outlined by Mr. Baruch was abandoned the whole United Nations plan to control atomic weapons and other weapons has achieved nothing. The United Nations Charter calls, as you know, for disarmament of the nations. It also calls for an armament of the UN. And under Article 43 of the Charter which calls for this armament a military staff committee is set up which is supposed to create in the United Nations Organization an armed force, which when coupled with disarmament of the nation states will be sufficient to put the UN in the position of being able to enforce the law against armament. As the matter stands today, I think it is fair to say that there is no serious effort on the part of anybody to give to the United Nations Organization these powers.

Let me at this point pick up what I said at the beginning as to what I believe is necessary to make out of the United Nations this limited world government. It is really relatively simple in its design, but it is a terribly difficult thing ever to get the nations to agree to. Very briefly, it is this:

It is the principle that the United Nations must be given both physical and the legal powers to enforce certain rules. Let me take up the rules first. The rules can be exceedingly simple. They can be embodied in a treaty, and they can provide that on and after the date of the treaty no nation will possess other than certain- specified minimum armaments necessary to enforce domestic peace. And, secondly, that the United Nations Organization will be given a military force which will be stronger than that of any nation or likely combination of nation states. Those two things together will give UN the physical power to enforce the rules.

The next thing is to give it the legal power. In order to give it the legal power —I am somewhat oversimplifying—all that is necessary is two things. First of all, to eliminate the veto whereby any power can block the enforcement of the law. And, secondly, to set up an amendment to the international court which would enable the international court to enforce the laws contained in the treaty directly upon the individual assenter.

Let us take a case to make it clear how that would work. Let us take the present row in Greece. What would happen would be this. Suppose that Greece made a complaint to the United Nations, a United Nations possessing these limited powers of law, and being a limited world government. The matter would be referred immediately to the Court of International Justice. The Court would find whether or not it was a fact that certain people were infringing the sovereignty of the northern Greek border. And it would find out who it was that was doing it. It would state that there are certain persons, whether they be Albanians, Yugoslavs or what not, who are infringing that sovereignty, and that they are violating the law of the world, and that immediately the United Nations Court shall order their arrest and cause them to be tried. The United Nations would then apprehend these people, as individuals. It wouldn't be the State of Albania, or the State of Yugoslavia. These individuals would be tried before a court. They could not resist because they wouldn't have the power or the military strength to resist their apprehension, and they would be assured of a fair trial under the processes of law. And such a thing would apply not only against small powers; it would also apply against the great powers. If, for example, it were charged that some citizen, some place in New Mexico, was manufacturing atomic bombs in violation of the law of the world, the United Nations Organization would cause this man to be apprehended and given a fair trial. And if he were found guilty of manufacturing atomic bombs or doing any other illegal act, he would be punished for it. The United States Government would be only too glad to collaborate in any such plan. The essential point that I am making here is that the jurisdiction is a jurisdiction over the individual.

I must now move on, if I may, for a moment or so more, to the question of what are the chances of our being able to do any of these things.

I repeat that I think that any plan to give to the United Nations control over immigration, emigration, tariffs and that sort of thing is hopeless at this time. I think that we may evolve to that at some time or other. But I think that there is a real chance that this limited world government, of which I have talked, is a feasibility. There is one very large stumbling block in the way, and it is not Russia. It is the United States. I think that at this moment the government of the United States has no more intention of doing any of the things that I am talking about here tonight, than of jumping to the moon. I believe the same accusation could be made against the people. I think that the people are completely apathetic toward this whole idea. I think a kind of numbness has overcome them since they were first struck by the horrible news of this new revolution in science which was made so dramatic at Hiroshima and Nagasaki. I think, therefore, that the enormous stumbling block is right here in this country. How that can be conquered I do not know.

I do know, however, that Mr. Stassen made a suggestion recently that there should be called a convention of the members of the United Nations under the provisions for that end in the Charter, and that there should be laid before this convention proposals to amend the Charter in order to make the United Nations work. If the United States were to call such a convention and if the United States were to make proposals for the amendment of the United Nations Charter to achieve these things, that conceivably might work. You may say Russia will never agree. I wish I had time to go into the main arguments on this point but unfortunately there is not time.

I would just like to summarize by saying that if we took that leadership there is a real chance that Russia would not dare stay out because any such organization as that would be proof that the western world was determined to live according to its standards and I think that Russia conceivably might make up its mind that it is to its economic and social advantage to join. But whether or not it did, at least the present system of having the states of the west scattered and divided among themselves would be at an end. At least the western world would be a determined and combined unit, determined to maintain its way of life. Perhaps it might have to fight it out with the Russians. I don't know. I personally don't believe it. I think that there would be such an elan of leadership that would come from that sort of thing that Russia and the rest of the world would follow.

But there is one thing of which I am absolutely sure. And that is that unless some such thing as this happens, and happens fairly fast, I think truly we are in for a war which would mean the end of our society.

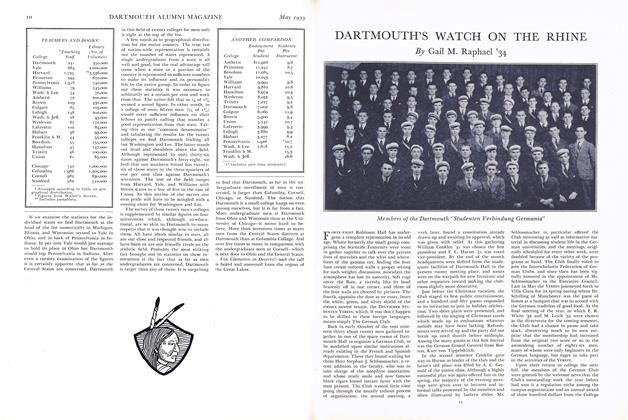

THOMAS K. FINLETTER, nationally known lawyer and citizen, who served recently as chairman of the President's Air Policy Commission. A leader in the effort to establish some form of world government, he states the essentials of his views in the Great Issues lecture here printed in full.

FORMER UNDER SECRETARY OF STATE, Dean Acheson, left, who opened the second semester of the Great Issues course on February 16, shown with President Dickey at the Carnival ski jump.

ON THE OTHER SIDE OF THE LENS: Adrian Bouchard, whose striking photographs are well known to Alumni Magazine readers, shown in a Christmas card pose with wife, Norma, and pet, Buckshot.

Mr. Finletter's lecture on World Government was given in the Great Issues Course on January 19. It was preceded by a lecture on The United Nations by Lester B. Pearson, Canadian Delegate to the General Assembly of the United Nations, and was followed by President Dickey's lecture on Dominant Characteristics of American Foreign PoliciesToday. This is the fourth full text which the MAGAZINE has been privileged to publish since the start of the course. Like those which preceded it, this month's text is presented in lecture form, as transcribed from the Great Issues recording machine.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleA HANOVER DIARY

March 1948 By PROF. LEON BURR RICHARDSON '00 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

March 1948 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR, DAVID L. GARRATT -

Article

Article"Suicide" Is Not for Cowards

March 1948 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1919

March 1948 By J. K. HUNTINGTON, MAX A. NORTON, ROSCOE A. HAYES -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

March 1948 By John P. Stearns '49 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1943

March 1948 By FRED F. STOCK WELL, WILLIAM T. MAECK, JOHN A. KOSLOWSKI