Dartmouth Skiers Flock to Bunny Bertram's Plunging Hill and Keep Trying to Be Wearers of the Coveted Gold "6"

NOT FAR FROM HANOVER a meadow smiles up to a benign Vermont sky in summer. In winter it is a sinister racing slope frowned on by Heaven and called by the skiing public Suicide 6.

The seductive smile of this snow siren of a hill should lead some Dartmouth man who understands fully her slippery allurement to rename her Sue Rueslide Hex, for she tempts Dartmouth men of all ages irrationally to flaunt their masculinity and to make an illusory conquest. Her only constant qualities are unpredictability and inconstancy.

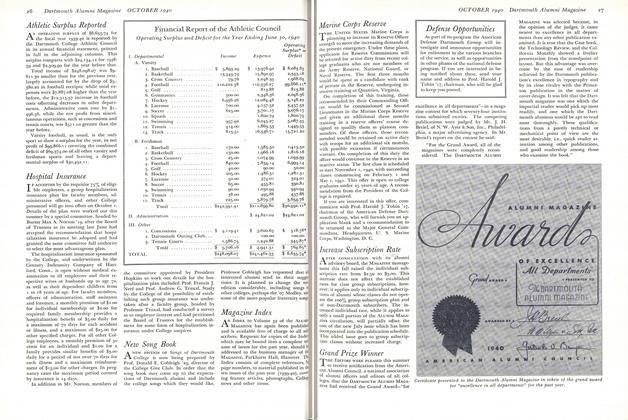

She belongs to no man for long, not even to Jack Tobin '42, who was so devoted to her that he took her back twice after she had twice given her favors to more reckless and faster men. It was not that Jack was a slowpoke. He was a speed demon who leaned far forward towards the tips of his skis and wore an automobile racer's helmet to prevent himself from getting concussion of the brain if he should crash into trees or boulders. He discontinued using the helmet because, so the rumor went, it caused too much wind resistance, and he got himself an extra short haircut.

Miss Hex's north-country charm appeals not only to Dartmouth men but also to many others, even to southerners who praise her and in the same breath often damn her. Insular westerners stick to their own mountains and have not tried for records on Suicide 6. Canadians have, and failed.

Miss Hex's representative on the hill. Bunny Bertram '31, distributes little emblems of brass, silver, and gold to men who within a certain number of seconds can ski over treacherous bumps, down pitches, past trees, over rocks, and through deep ruts from top and bottom and live. The insignia in the form of a 6 indicates that the wearer is in the lady's graces, the degree depending on the preciousness of the metal. If he has skied from the far top to the far bottom in 90 seconds, it is bronze; if in 60, silver; if faster than anyone ever has before, gold. Some of the bronze ones look as if they had been shined up with yellow wax.

Of the 22 skiers now wearing the gold, most of them easterners, six are Dartmouth men. The most dramatic of them, Jack Tobin, broke the record three times in one day, March 24, 1940. That day contained some of the most spectacular skiing ever seen on Suicide 6, for the record was broken seven times, six times by Dartmouth men and once by the Swiss pro, Karl Acker.

About a half mile long, Suicide 6 has an average grade of 20 degrees with the steepest about 30. Naturally bumpy, the deeper the snow the bumpier it becomes. No roughnesses are smoothed out by hand voluntarily, but some are by other portions of the anatomy involuntarily.

To get back up, a skier must spend at least a half hour herringboning under his own power or ride the charmer of a tow, which turns out to be a witch of a ride. The speed of 16 to 20 miles an hour seems faster on the pitches. A complication for the uninitiated is that ski poles may not be hung by the straps on wrists but must be carried loose under the left armpit, and mechanical ropeholders are forbidden. Many persons consider that the strains and aches involved in just one ride up are worse than the falls involved in skiing down. Behind agonized hands and arms a rider and his back are tortured up the hill in an eternity of 67 seconds. A large number on their first day out, even rugged Dartmouth football players, must quit after six rides. The iron strength of hands and shoulders turn to marshmallow under the strain of trying to keep wet mitts from slipping on the snowy rope. Grimacing countenances coming up the last pitch remind spectators of ham actors in a melodrama endeavoring to register hate.

When in 1937 Alex Bright ran Suicide 6 in 56.8 seconds, the skiing world was amazed and believed that probably this record would never be broken. It was unthinkable that anyone could go any faster and live or go any faster, period. Yet three years later Jack Tobin '42 ran down the tow path and cut the record by 23.8 seconds. Since 1937 the record has been broken 24 times, an expense for Bunny because he gives away free gold 6's, but he makes up his losses by charging a half dollar for the silver and bronze. Even a Dartmouth professor, aged 47, skied Suicide 6 in 56 seconds in 1947, and a small Woodstock boy, aged eight, Dicky Swanson, also won his silver 6, though by virtue of not having yet shaved he was allowed to compete under women's rules which award it to any female able to complete the run in 90 seconds. He did it in exactly 90.

The best time this winter up to the second week in January, made by Rene Ravoire, the Swiss professional with the Allais technique who gives lessons at Bunny's, was 44.4, which was considered excellent because the hill had not been broken out, the snow was powder, and the bumpiness was particularly bad.

During the Dartmouth Carnival week end, however, an amateur from Woodstock, David Austen, knocked four-tenths of a second off the pro's time, but 40 seconds is slow for David. He has skied Suicide faster than anyone now living, and he did it when he was only 17. The present record of 31.8, which he made in the spring of 1947, is even more commendable when one thinks of the joint-chattering schuss down the no-man's-land center of the hill. Skiers on both sides hold their breath for half a minute when contestants swoop down so delicately poised that it seems a person's breathing could blow them off course, though the blast of their passing is more likely to knock the breather flat.

30 SECONDS CONSIDERED LIMIT

Experts on Suicide 6 this year prophesy, with as much assurance as the bright commentators who proved a little dim, that 30 seconds is as fast as Suicide 6 can be skied and even then only before 10:30 on a perfect spring morning in corn snow.

Some innovators believe that aluminum skis may be the answer to the quest for higher speeds, but only a few pair are appearing on Suicide 6 this winter. John Jay, the photographer and author of the film Singing Skis and of the new book Skiing the Americas, tried them one day there. After skiing in cold hard-packed snow and then right afterwards in warm deep snow on the other side of the tow, where he took what onlookers described as a beautiful spill, he discovered that the metal bottoms were iced up the whole length. Bunny dislikes them because they rough up the hill. Their edges seem sharper than the steel edges on wooden skis. Aluminum skis still await thorough testing on corn snow. They may some day turn out to be a powerful weapon on the feet of worthy christie knights in pursuit of the magic trail.

Surrounded by four tows and slopes ranging from baby to giant, Bunny has not put on a ski since 1940 when he was out west. Feeling suddenly free and reckless, he even entered a race. Since then he has spent most of his winters at the safety switch on the top of Suicide 6, standing on a box in a vain attempt to keep his feet out of the snow enough to remain uncongealed. He does not worry much, for accidents occur rarely on 6, partly because tow and hill are so rugged that only experts attempt it, though some dubs do go hacking down injuring themselves and others. More persons are hurt on the two intermediate hills on the other side, and the greatest number of casualties occurs on the beginners', which is of course no paradox.

Throughout the week Suicide 6 is skied mostly by Dartmouth men, and consequently there is something clublike and friendly about it. Bostonians and New Yorkers flock in week ends, but even so there are only about 375 skiers a day maximum on all four of his tows, a small number compared to Stowe's 3,000 and North Conway's 5,000. Before the war Bunny sometimes had 750, but, having raised the tow fee from $1 to fa, he makes as much money and the skiers get better service.

Machine minded, the younger generation ask almost as many questions about the Suicide 6 power plant as they do about snow conditions. It is a 35 horse power electric motor which he bought for only $150; he found it in the basement of a building between Lebanon and West Lebanon where it was used infrequently to pump out water in times of flood. Bunny does not know what he would do if it should break down; it never has. Nor has the rope for Suicide 6 ever broken. He uses 3,100 feet costing him $500. It lasts him two years, and then no matter if it still looks unfrayed, he throws it away. He will neither sell it nor give it away, and he is indignant with anyone who tries too hard to buy or beg it.

BUNNY STICKS TO GALOSHES

In an attempt to get him back on skis, girls often turn on their charm, but he is content to slide in a stumbling fashion on galoshes. As intimate of many skiers, he spends many hours a day talking in modern terms to modern enthusiasts, but he is likely to reminisce romantically in oldfashioned terms to old timers. He likes to recall that his favorite method of waxing was a technique Dartmouth undergraduates have only read about, klister in great gobs a quarter of an inch thick. Then he would shy away from the beaten hills to the unbeaten with good thick corn snow which he could climb straight up because the klister acted like climbing wax. On top he would scuff his skies a couple of times to make them ready to slide. Thousands of icy particles had sunk into the klister, but downhill friction melted them off, and their places were filled with air that lightened his skis and gave him the delightful sensation of skiing on air or of aquaplaning.

"That's old stuff now," he philosophizes. "Modern skiers rave about powder. 'lf only we could have about a foot of powder,' they say, but when it comes they don't know what to do with it. So they go like mountain troops one after the other in the same trail until they wear it all down in a series of curved grooves with hard surfaces. They take the turns in the same places, for they cannot ski if they cannot skate. Look at the wideness of 6. Westerners and Europeans would all love this open slope, but Easterners are all trail addicts."

As he finished his sentence, an enthusiast proved his point. He got out of the narrow trail by mistake and shot over into about ten inches of powder. Attempting to turn back to civilized hardness, he disappeared in a foaming cascade of snow.

"See what I mean?" said Bunny raising his eyebrows. "He's out of control. Control is what Vermonters used to have 50 years ago when they used to hay Suicide 6. They got the hayyricks down it with horses in front and oxen in back to keep them well anchored."

Mrs. Bunny, possessor of a daughter, Suzanne, aged about eight months, and of a silver 6, aged about two years, follows the French pro, Rene Ravoire (formerly Allais's right-hand man, so it is said) and some of the best local skiers even when they lead her on the unbroken sections of 6. She is typical of the young women who ski the slope these days; they schuss it just like men. And they try for men's records, which they simply cannot equal, though not for lack of courage. The present women's record of 41.8 seconds, held by Eleanor Sharpe, two years out of Woodstock High School, aged 19, is a full ten seconds slower than the 31.8, set by Dave Austen, also out two years, aged 18. Some persons believe that women being lighter in weight cannot go so fast, but the differences in weight between the best men and women skiers at Woodstock are negligible. Nor are there any 200- pound champions.

HANOVER GIRLS LEADERS

In these days of Andre and Saks, women whether standing still or running on skis look both pretty and expert. Their ratio to men on Suicide 6 is about one to 16. In consequence their styles stand out more clearly. Many Dartmouth students spend as much time watching some of the better girl skiers as they do skiing themselves and giving them full credit: Jane Gile Chivers and her sister Nancy, daughters of Dr. John F. Gile '16; Patsy Bowler, daughter of Dr. John P. Bowler '15; the Neidlinger sisters, Mary, Sally, and Sue, daughters of the Dean; the Dent sisters, Barbara and Jean, daughters of the Coach; Betsy Bankart, daughter of Laurence H. Bankart '10; and Ruth Marie Stewart who skied with Colin Stewart '48 on the U. S. Olympic team in Europe.

Outstanding among the women skiers at Suicide are the Neidlingers, for Sally holds the downhill record for women and Sue won the slalom there during the recent Dartmouth Carnival weekend at the time that Malcolm McLane, Dartmouth ski captain, was winning the Fisk Trophy in the men's.

If a woman should ever break the present Suicide 6 record for men, Bunny has an undeveloped slope on the other side of the tow with a vertical drop of nearly 90 degrees, which makes the Nose Dive seem flat. Some Dartmouth men say that they would like to try it. According to rumor, it has a speed close to that of sound.

IT LOOKS GENTLE ENOUGH from the air but to the skier at the top of the hill peering down Suicide Six looks like the anatomy bumper it is.

JACK TOBIN '42, who broke the Suicide record three times in one afternoon and whose 33 sec. run in 1940 is still the best by a Dartmouth skier.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleWORLD GOVERNMENT

March 1948 By THOMAS K. FIN LETTER -

Article

ArticleA HANOVER DIARY

March 1948 By PROF. LEON BURR RICHARDSON '00 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

March 1948 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR, DAVID L. GARRATT -

Class Notes

Class Notes1919

March 1948 By J. K. HUNTINGTON, MAX A. NORTON, ROSCOE A. HAYES -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

March 1948 By John P. Stearns '49 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1943

March 1948 By FRED F. STOCK WELL, WILLIAM T. MAECK, JOHN A. KOSLOWSKI

JOHN HURD '21

-

Article

Article"Janssen Plan for Peace"

OCTOBER 1958 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Feature

FeatureDid Webster Really Say It?

JANUARY 1966 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksTHE SEA WITCH

JULY 1968 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksPAGE 2, THE BEST OF "SPEAKING OF BOOKS" FROM THE NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW.

FEBRUARY 1969 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksJOHN MILTON. PARADISE LOST, PARADISE REGAINED, AND SAMSON AGONISTES.

MAY 1969 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksP AS IN POLICE.

JANUARY 1971 By JOHN HURD '21