Students' Spring Trip Highlights Ecology Program

GROWING OUT OF the old Natural History Club, the Dartmouth Ecological Society was formed last fall by a group of students interested in the discussion and investigation of the relationship of plants and animals to their environment arid to the. activities of man. The society's first year of activity, under the direction of Douglas E. Wade, College Naturalist, has been a full one, with regular Thursday night meetings, two sponsored lectures, camping and tracking trips, participation in the College Naturalist's peregrine falcon and woodcock projects, and, perhaps most important of all, the preparation and sponsorship of a full-scale Baker Library exhibit on the conservation of natural resources, tying in with the consideration of that topic by the Great Issues Course. A three-man panel from the society also took part in the Tuesday morning discussion following the Great Issues lecture by Dr. Hugh H. Bennett, chief of the U. S. Soil Conservation Service. This 1947-48 program has given the Dartmouth Ecological Society a solid start and has demonstrated the fact that ecology is a very broad field, encompassing nearly all areas of human endeavor as well as most of the disciplines of a liberal arts college.

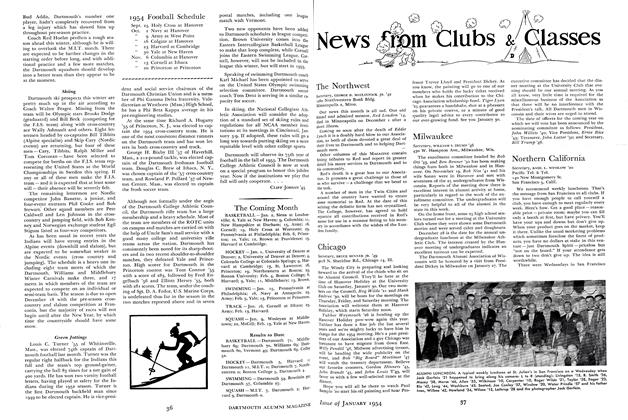

High spot of the year, however, for seven members of the society was something beyond this "regular" program. It was the spring-vacation field trip to the Outer Banks of North Carolina—a "funwhile-learning" proposition that made no attempt to live up to all the strict scientific procedures of larger-scaled expeditions but which nevertheless accomplished a good deal and proved to be a worthwhile and inexpensive way to spend the spring vacation.

The expedition had as its objective an ecological study of the wildlife and plant life of the Cape Hatteras region, as well as an investigation into the sociologic and economic status of the people. The men who went on the trip were chosen for their ability and interest in one of several fields. H. Burton Hicock '45, a psychology major, was especially interested in visiting some of the schools and interviewing some of the Island people. Franklin R. Stern '48, a geography major, was to attempt to determine the relationship of the economic conditions to the geographical peculiarities of the Outer Banks. William J. Schaldach '46 was to make a collection of small mammals, and try to get an indica- tion of mammal populations. James E. Schwedland '48 and John A. Gustafson '48 were to work with the plant and insect life. Jay S. Haft '49 was official photographer. Schwedland was also to obtain and analyze soil samples. Douglas E. Wade, College Naturalist, acted as director of the expedition.

STATE AND FEDERAL AGENCIES HELPFUL

A great deal of help was received from Bill Sharpe of the North Carolina Department of Conservation and Development, and from the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the National Park Service, the Photographic Division of the U. S. Air Force, and the Wilderness Society. All of these agencies evinced much enthusiasm for the trip as planned and gave us splendid cooperation.

The original plan was to get to Hatteras Island and to make a strip survey of soils, plant and animal life across the Island near the town of Buxton. We intended to catch the ferry from Engelhard, North Carolina, for Hatteras Village at 3:00 p.m. on Saturday, March 27. Leaving Hanover at 5:00 a.m. March 26, we drove continually the 850 miles, switching drivers and resting on the ferry rides across the Delaware River and Chesapeake Bay. En route we stopped at Sharptown, New Jersey, to visit the ice cream plant of Doug Wade's father-in-law (Richman's ice cream). While we were standing there eating up the profits of the plant, a woman came over and asked if we were all from Dartmouth College. She had seen Burt's numerals on his green sweater. She and her husband, Royal B. Hassrick '39, and three sons, gave us an enjoyable experience of meeting a loyal Dartmouth family. They invited us to spend the night with them at their pre-Revolution house, Seven Stars, but we had to push on.

The next morning we were able to see a little of the Great Dismal Swamp in Virginia, and crossed through the center of the Mattamuskeet National Wildlife Refuge south of Columbia, North Carolina, where we saw several hundred Canada geese and three whistling swans. With luck (only one flat tire) we made it to the ferry at Engelhard with fifteen minutes to spare, but found that Pamlico Sound was so rough, and the ferry so small, that it would be impossible to make the threehour trip without subjecting the cars to a thorough salt-spraying and subsequent corrosion, against which they were not protected. The prospect of having nothing left to travel home on but the seat cushions and the tires was not particularly appealing. So, with the enthusiastic assistance of the local constable, who very obligingly and speedily escorted us on our way to Mann's Harbor, we got a more substantial (and, we might add, free) ferry across a much narrower and calmer part of the Sound.

The Mann's Harbor ferry took us to Roanoke Island, where we pitched camp near the site of the Lost Colony, established by the English under Sir Walter Raleigh in 1587. Situated in a comfortable loblolly pine grove, we spent most of Sunday morning recuperating from the ordeal of the trip down. Sunday evening we went to Manteo to visit Paul Sturm, refuge manager of the Pea Island National Wildlife Refuge, whom Doug Wade had written earlier. When he heard of our change in plans, he offered us the use of the Refuge Manager's cabin on Pea Island (which is actually the northern end of Hatteras Island), and we made plans to drive down on Monday morning. We stayed at the Sturms' until midnight, entertaining them with our repertoire of Dartmouth songs and Jim Schwedland's fancy guitar strumming

Five-thirty Monday morning was clear and cold, and after a hearty breakfast provided by the hospitable Sturms, we started in two refuge trucks down the sandy beach road to Oregon Inlet, where a ferry took us from Nags Head Island to Pea Island. After leaving the ferry and deflating the tires somewhat to permit easier running on the sand, we drove out onto the hard-sand beach. All along the way we saw flocks of Canada geese feeding in the marshes, and there were many ducks, gulls, and shore birds which tested our ability at identification.

VARIED PROJECTS UNDERTAKEN

The next four days on the refuge gave us little time to delve deeply into the many absorbing and time-consuming projects which came to our attention. We identified and counted birds; studied the peculiar habits of a large trap-door spider; captured horseshoe crabs and dug clams, experimenting with the latter in "chowder" and on the "half-shell"; collected plants of the sand dunes and marshes; photographed a dory-load of 1400 saltwater Maryland terrapin (pronounced "tappin" by the local sea captain); trapped rodents and tracked otter; counted muskrat houses and green-winged teal; beachcombed and went swimming (the temperature of the water, we found, was not much affected by the Gulf Stream at that point); and rescued people whose cars had become stuck in the sand.

The muskrat survey was perhaps one of the most interesting and complete ac- complishments of the trip. A large fresh- water pond near the cabin was encom- passed by about 500 acres of marsh dotted with muskrat houses and platforms. We worked this area two days in shifts of three at a time in hip-boots, counting all houses, feeding platforms, bank-dens, and feeder houses that showed signs of being presently used. In one house that we opened we found two week-old muskrats. As a result of this complete survey we were able to estimate the approximate number of muskrats in the pond, and thus obtain a better idea as to how they might affect the waterfowl. We were also introduced to the travel routes and feeding habits of the otter, although there was little time to make a thorough investigation. We concluded that there were at least a dozen otter in the refuge.

On Tuesday afternoon we visited Ro- danthe, the first town south of the refuge, on Hatteras Island. Here there were two LST's beached broadside on the sandy shore, having broken loose from a tow boat during a storm and come ashore about three miles apart. Jim Schwedland, an old LST man from his Navy days, attempted to convince us that he knew an easy way to get them free, but the owners (no longer the Navy) had decided to dismantle them for scrap on the spot. The town of Rodanthe is an artist's dream of picturesque houses and unpainted shanties. Burt Hicock was able to find out from the local store keeper that all but five families in the town were named Midgett —an interesting phenomenon of the Outer Banks region, where it seems that almost everyone is a Midgett, or related to one.

We were just getting the "feel" of the Island when Thursday evening rolled around and we reluctantly had to pack up and start back to Hanover. The Sturms generously invited us to shower and shave at their home in Manteo Thursday night. The array of fancy beard designs resulting outdid Little Orphan Annie and Lil'Abner combined. Refreshed and rested, we were on our way early Friday morning, driving by way of Kitty Hawk, where we stopped at the Wright Memorial. Later that day at Williamsburg, Virginia, we saw President Truman and Prime Minister Mackenzie King shortly after they had received degrees from the College of William and Mary. Friday night we inspected the Jefferson-designed University of Virginia, where our Indian yells mingled not too gently with the atmosphere of the classic halls and campus.

We camped along the Skyline Drive, in the Shenandoah National Park, and Saturday morning we enjoyed a beautiful ride along the Drive, with redbud and bloodroot in bloom all the way. Our route then took us through the narrow parts of West Virginia and Maryland, and then up the Susqehanna River valley of Pennsylvania, where we hoped to see some coalmining towns, and did see plenty of Pennsylvania-Dutch barns. Saturday night we rolled up in our sleeping bags in somebody's pasture near Afton, New York. Sunday, the leisurely drive back to Hanover through Saratoga Springs and Glens Falls was a very pleasant finale to a successful trip.

It is the consensus of all that another trip to the Outer Banks should be planned for next spring vacation. Besides the great personal gain attained by each member of the trip in being able to apply some of his classroom work to field practice, there is an equal opportunity for much valuable information to be gathered about the nature of these interesting islands, toward the better management and use of them for recreation and wildlife protection. Here is an area comparatively undeveloped which, if proper and sufficient study is made of it, can be used in a variety of ways without detriment to its charming remoteness and unique character. Needless to say, the experience gained by the students in such a project would be invaluable.

According to the Trail-Blazer of the DOC, commenting on the recent Woodsman's Weekend, "emphasis is placed on being an all-around good woosman, rather than on being proficient in one particular phase."

Do we hear cheers from Northampton?

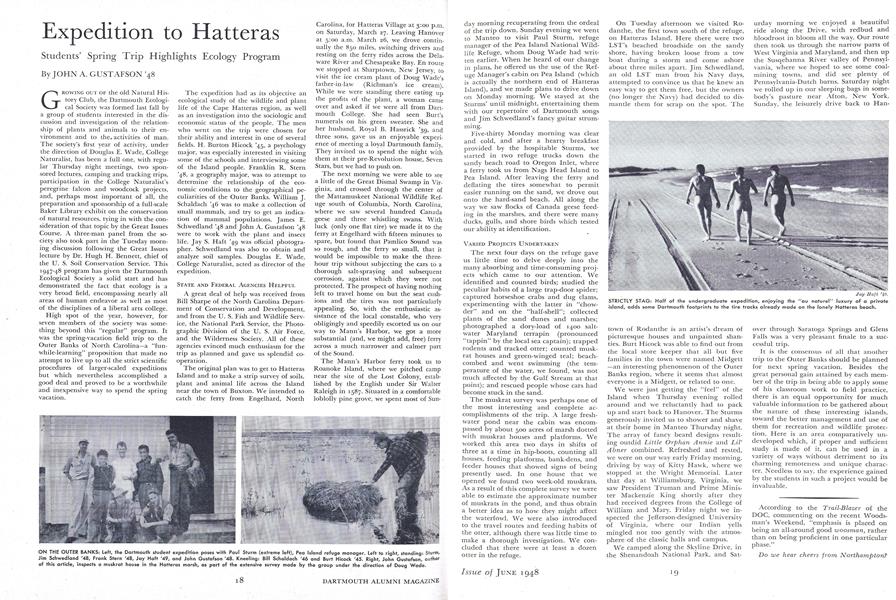

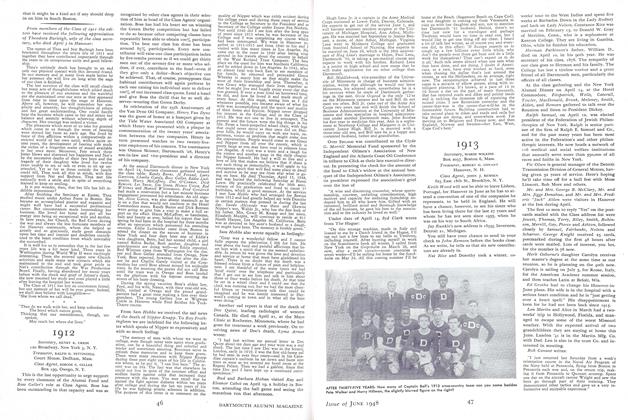

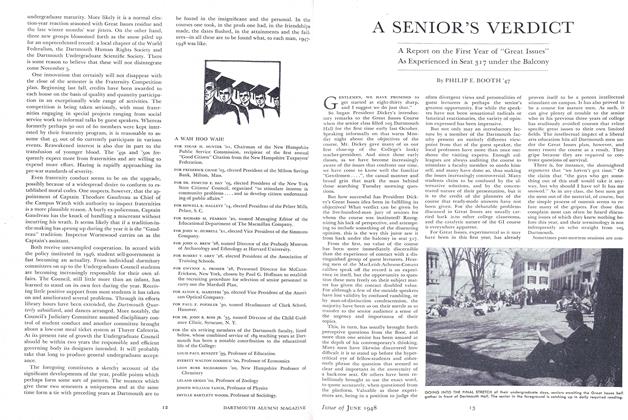

ON THE OUTER BANKS: Left, the Dartmouth student expedition poses with Paul Sturm (extreme left), Pea Island refuge manager. Left to right, standing: Sturm/ Jim Schwedland '48, Frank Stern '48, Jay Haft '49, and John Gustafson '48. Kneeling: Bill Schaldach '46 and Burt Hicock '45. Right, John Gustafson, author of this article, inspects a muskrat house in the Hatteras marsh, as part of the extensive survey made by the group under the direction of Doug Wade.

STRICTLY STAG: Half of the undergraduate expedition, enjoying the "au nature!" luxury of a private island, adds some Dartmouth footprints to the tire tracks already made on the lonely Hatteras beach.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Books

BooksDeaths

June 1948 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

June 1948 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR, DAVID L. GARRATT -

Class Notes

Class Notes1912

June 1948 By HENRY K. URION, RALPH D. PETTINGELL, ROSCOE G. GELLER -

Article

ArticleA SENIOR'S VERDICT

June 1948 By PHILIP E. BOOTH '47 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1943

June 1948 By FRED F. STOCKWELL, WILLIAM T. MAECK, JOHN A. KOSLOWSKI -

Class Notes

Class Notes1919

June 1948 By J. K. HUNTINGTON, MAX A. NORTON, ROSCOE A. HAYES

JOHN A. GUSTAFSON '48

Article

-

Article

ArticleTHE PRESIDENT'S FALL ENGAGEMENTS

December, 1911 -

Article

ArticleADDRESSES UNKNOWN APRIL 6, 1916

May 1916 -

Article

ArticleFull Time Students

May 1939 -

Article

ArticleThe Coming Month

January 1954 -

Article

ArticleTuck School Contributors

December 1956 -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH AND THE SECONDARY SCHOOLS

February 1916 By James L. McConanghy