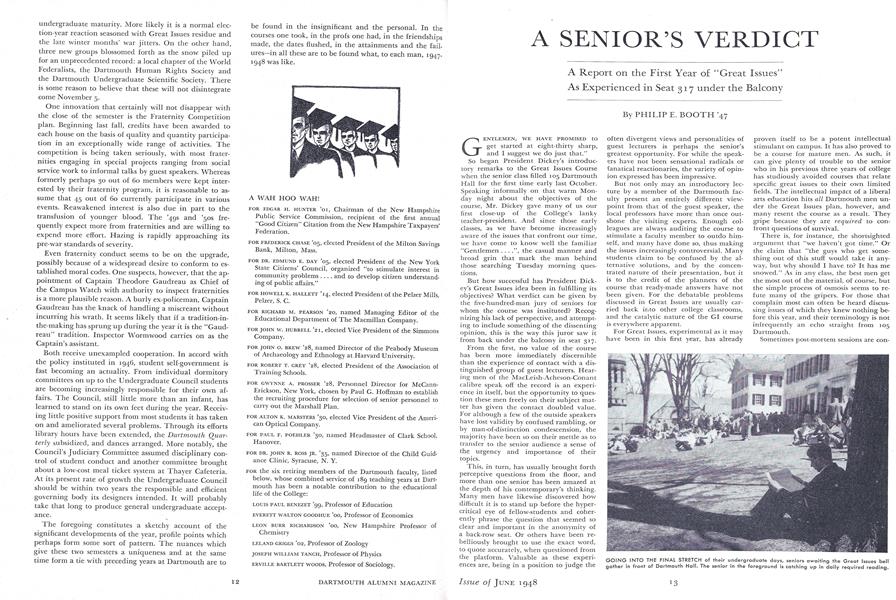

A Report on the First Year of "Great Issues" As Experienced in Seat 317 under the Balcony

GENTLEMEN, WE HAVE PROMISED to get started at eight-thirty sharp, and I suggest we do just that." So began President Dickey's introductory remarks to the Great Issues Course when the senior class filled 105 Dartmouth Hall for the first time early last October. Speaking informally on that warm Monday night about the objectives of the course, Mr. Dickey gave many of us our first close-up of the College's lanky teacher-president. And since those early classes, as we have become increasingly aware of the issues that confront our time, we have come to know well the familiar "Gentlemen . . . .", the casual manner and broad grin that mark the man behind those searching Tuesday morning questions.

But how successful has President Dickey's Great Issues idea been in fulfilling its objectives? What verdict can be given by the five-hundred-man jury of seniors for whom the course was instituted? Recognizing his lack of perspective, and attempting to include something of the dissenting opinion, this is the way this juror saw it from back under the balcony in seat 317.

From the first, no value of the course has been more immediately discernible than the experience of contact with a distinguished group of guest lecturers. Hearing men of the MacLeish-Acheson-Conant calibre speak off the record is an experience in itself, but the opportunity to question these men freely on their subject matter has given the contact doubled value. For although a few of the outside speakers have lost validity by confused rambling, or by man-of-distinction condescension, the majority have been so on their mettle as to transfer to the senior audience a sense of the urgency and importance of their topics.

This, in turn, has usually brought forth perceptive questions from the floor, and more than one senior has been amazed at the depth of his contemporary's thinking. Many men have likewise discovered how difficult it is to stand up before the hypercritical eye of fellow-students and coherently phrase the question that seemed so clear and important in the anonymity of a back-row seat. Or others have been rebelliously brought to use the exact word, to quote accurately, when questioned from the platform. Valuable as these experiences are, being in a position to judge the often divergent views and personalities of guest lecturers is perhaps the senior's greatest opportunity. For while the speakers have not been sensational radicals or fanatical reactionaries, the variety of opinion expressed has been impressive.

But not only may an introductory lecture by a member of the Dartmouth faculty present an entirely different viewpoint from that of the guest speaker, the local professors have more than once outshone the visiting experts. Enough colleagues are always auditing the course to stimulate a faculty member to outdo himself, and many have done so, thus making the issues increasingly controversial. Many students claim to be confused by the alternative solutions, and by the concentrated nature of their presentation, but it is to the credit of the planners of the course that ready-made answers have not been given. For the debatable problems discussed in Great Issues are usually carried back into other college classrooms, and the catalytic nature of the GI course is everywhere apparent.

For Great Issues, experimental as it may have been in this first year, has already proven itself to be a potent intellectual stimulant on campus. It has also proved to be a course for mature men. As such, it can give plenty of trouble to the senior who in his previous three years of college has studiously avoided courses that relate specific great issues to their own limited fields. The intellectual impact of a liberal arts education hits all Dartmouth men under the Great Issues plan, however, and many resent the course as a result. They gripe because they are required to confront questions of survival.

There is, for instance, the shortsighted argument that "we haven't got time." Or the claim that "the guys who get something out of this stuff would take it anyway, but why should I have to? It has me snowed." As in any class, the best men get the most out of the material, of course, but the simple process of osmosis seems to refute many of the gripers. For those that complain most can often be heard discussing issues of which they knew nothing before this year, and their terminology is not infrequently an echo straight from 105 Dartmouth.

Sometimes post-mortem sessions are conducted over a glass of beer and deal casually with the personalities of speakers, or with the outstanding repartee of men like Llewellyn White or Beardsley Ruml. Other more serious arguments are perhaps concerned with the meaning of liberalism, or with various art forms, and these discussions often keep fraternity lights burning much of the night. And the question always comes up: "What is a great issue, anyway?" Some answer that any issue is an entirely personal matter based on the possibility of freedom of choice: A Government major may quote ex-Secretary Stimson: "Can we make freedom and prosperity real in the present world?" But if for him the great issue is modern man's political loyalties, for a Physics major the important question probably concerns atomic energy.

Whatever the individual student's concern, be it with world government or religious values, the scope of the Great Issues course has given all seniors a humbling sense of the complex interrelation of the central issues that confront their generation. They can relate what they hear in Dartmouth Hall not only to one other course, but to their whole educational experience. A few seniors, indeed, have already realized that they must somewhat surbordinate their future to the public purpose if they are ever going to see any of the great issues resolved. As one Air Force veteran said: "The war just gave me a longing for security. But now I'd like to do something really constructive, not just go into my father's packing business."

For him the course has certainly met its objectives of "developing a greater sense of the common public purpose, of providing a transition from the general classroom to the responsibilities of adult education." With this particular man, the effect has been immediate. But for most of us, final exams have been over too recently for anybody to judge, except by meaningless letter-grade, the real worth of this educational experiment. Ten years, perhaps, can prove something of its true significance.

For the average senior buried in a pile of newspapers as he writes his special project evaluating the treatment of the news, the social significance of the course under standably seems small. Tuck, Thayer, and Medical School men find the burden of assignments especially distasteful, but members of the Steering Committee on duty in the Public Affairs Laboratory have often to lend a patient ear to other senior complaints. Much criticism is, of course, leveled at this faculty committee itself, for although a particularly irritating lecturer leaves Hanover soon after his speech, the course executives remain as scapegoats. They likewise hear all fault-finding with the mechanics of the course, and these are many: "The exam was unfair There's too much reading assigned This term paper's the most worthless thing I ever did First you call this place a laboratory and next year you're going to let that scientist run it What are you trying to do, make this college into another Harvard?" And so on, ad infinitum.

It should be realized, however, that both deserved and undeserved criticisms usually reach, and are often anticipated by, the Steering Committee. Meeting with that body at the President's house this spring, ten men invited to represent senior opinion were encouraged to pull no punches in criticising the course. As they commented freely on all phases of Great Issues, the students found willing listeners in President and faculty, and left the session at midnight feeling that thoughful undergraduate opinion had more than a token voice in giving the course direction. And although such discussions are often pretty forced, the success of this last session seems indicative of the naturally cooperative relationship that can be achieved in even as large a course as Great Issues.

Unfortunately, this year's seniors have been overly aware that they are the original Great Issues guinea pigs, and have sometimes been on the defensive as a result. Acceptance of the course will be more natural for succeeding senior classes, and cooperation will correspondingly increase between students and Steering Committee. Indeed, if the student opinion expressed at the President's House is any indication, incoming freshmen may begin to point their whole education toward its culmination in Great Issues. For one of the main questions asked was: "Why do we have to wait until the senior year to get this stuff?" And another student said: "All my courses would have meant more if I'd known something about these issues when I was a freshman." Such comment is not only high tribute to the course as it exists, but shows the sort of constructive criticism that this common intellectual experience can generate.

Should "Small Issues" eventually become a part of the Dartmouth freshman curriculum, it would probably follow the precedent set by its older brother in evolving an individual idiom. For not only has the intellectual experience of Great Issues been a unifying force for seniors whose classes range from '43 through '49; it has provided them with a common language. When in October you asked your roommate: "Are you going to Great Issues?", he might answer "No, I'm going to cut." But by midyears you were both more sophisticated: "C'mon, let's hit the Issue, Joe!" "Nope, can't see it. Gonna flush Gray Tissues this time " So you go to class and Joe cuts, or you both go and Joe reads The American Magazine while the speaker quotes Thomas Jefferson. In any case, there's the saving remnant—indeed, the saving majority—that can some day prove Great Issues great.

For while a majority of Dartmouth seniors are aware of the opportunities offered by the course, some quite naturally shut their minds to the unpleasant realities of the world. Others have not yet realized the existence of those realities and find the great issues dull abstractions. But for those students who as members of the "creative majority" recognize their responsibility to the future, Great Issues is of immediate import. And if, as President Dickey said in that opening class last fall, "The central need of society is to bring into better balance the utter physical power men now possess as against their moral and political controls of that power," the Great Issues course is, in leveling the scales, more than fulfilling its responsibility to the liberal college community. But how much it contributes to the need of society as a whole will depend only indirectly on lecturers, steering committee, or New York Times. That contribution can come only from the graduates of Great Issues themselves. How much they will contribute, whether they will give in time, is itself a great issue.

GOING INTO THE FINAL STRETCH of their undergraduate days, seniors awaiting the Great Issues bell gather in front of Dartmouth Hall. The senior in the foreground is catching up in daily required reading.

STUDENT JUROR: Philip E. Booth '47, author of this article on the first year of Great Issues. One of the many married seniors at Dartmouth, he served in the U. S. Army Air Corps and is the son of Edmund H. Booth '18, Professor of English.

FAMED THEOLOGIAN VISITS COURSE: Dr. Reinhold Niebuhr, who gave a stirring Great Issues lecture May 10 on faith in the scientific age, discusses some of the course objectives with two seniors in the Public Affairs Laboratory in Baker. Left is Phillip R. Viereck '48 and right, Raymond E. Millemann '49.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Books

BooksDeaths

June 1948 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

June 1948 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR, DAVID L. GARRATT -

Class Notes

Class Notes1912

June 1948 By HENRY K. URION, RALPH D. PETTINGELL, ROSCOE G. GELLER -

Article

ArticleExpedition to Hatteras

June 1948 By JOHN A. GUSTAFSON '48 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1943

June 1948 By FRED F. STOCKWELL, WILLIAM T. MAECK, JOHN A. KOSLOWSKI -

Class Notes

Class Notes1919

June 1948 By J. K. HUNTINGTON, MAX A. NORTON, ROSCOE A. HAYES

Article

-

Article

ArticleJOHN KING LORD '68

February 1920 -

Article

ArticleSCHOLARSHIP PLAQUE GOES TO SOMERVILLE

April, 1922 -

Article

ArticleFraternity Conference

February 1946 -

Article

ArticleNew York City

NOVEMBER 1969 By BRUCE FRIEDLICH '41, CHARLES S. MCALLISTER JR. -

Article

ArticleDown-East Argonaut

March 1977 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleGood Plays for Reading

December 1933 By Prof. E. B. Watson