IN JUNE I happened to see George H. Pasfield '2B in the Dragon tomb and somehow we got talking about Lincoln. This led to his sending me a book by his brother-in-law Benjamin P. Thomas called Portrait For Posterity (Rutgers University Press, 1947) which is a detailed, well-written, humorous, and at times exciting account o£ Lincoln's biographers from the outspoken and debunking Herndon to the poet Carl Sandburg. I have found this book a mine of interesting information. It is indispensable for any student of Lincoln and I think the general reader, whoever he may be, will find it interesting too. There are fifteen pen and ink drawings of the writers on Lincoln by Romaine Proctor. I am immensely indebted to George Pasfield, and to the author for several entertaining hours. And I do know more about Lincoln, a man who with each scanning of the day's news, becomes more and more a gigantic figure of a vanished American. Measure Lincoln with the political mountebanks of our time and one is apt to turn to the phonograph (I am oldfashioned) and play "There is Nothin' Like a Dame."

William Stuart Messer, Latin teacher extraordinary, good friend of many years and bon vivant— that is, a lover of all good things—sent me The Cautious Husband (Coward-McCann), written by Virginia Evans, wife of Bob Evans '4l. This is the story of a young married couple living in the equivalent of Sachem Village or Wigwam Circle, though in this particular case the locale might very well be the University of Michigan where Mr. Evans and his wife lived after he had graduated from Dartmouth. Mr. Messer thinks, and I agree with him, that this book will be found interesting and even self-revealing to all young married couples who have been living under, and by, the G.I. bill. Mrs. Evans writes with an easy facility, the dialogue is natural and lively, and the husband is well dissected and lovingly stuck on a board. At the end the wife learns tolerance, and all seems well. The ending is weak but as a picture of young married people of the forties it will pass muster. I will look forward to Mrs. Evans' next novel with considerable interest.

Through the good works of A. F. Tschiffely I was able to purchase a first edition of a remarkable book Uttermost Part ofthe Earth (London: Hodder and Stoughton), about forty years of life in the wild, desolate and beautiful land of Tierra del Fuego. The author's father was a missionary in this savage land, and the book is a biography of this man, Thomas Bridges, an autobiography of the son, Lucas Bridges, who wrote the book, as well as a history of the legendary Ona Indians and of the land itself. Mr. Lucas, who died soon after the book was out, is not as great a writer as W. H. Hudson or R. B. Cunninghame Graham, but he is a great personality, and his is nearly a great book. I am almost certain that any of you who like to read travel books of unusual places will enjoy this one.

One of the most civilized and urbane of books read this past summer is Osbert Sitwell's Laughter in the Next Room (Macmillan, London, 1949). This is the fourth volume of a long and detailed autobiography and covers the period roughly from the Armistice in 1918, with reminiscences of the war in Flanders, to about the present. Famous people flit through the pages in most amusing fashion, and Sitwell reveals himself as a man of culture in about the best sense of that abused word. Highly recommended.

In reading Henry L. Mencken's AMe?icken Chestomathy, a hefty volume of 627 pages, I found myself agreeing with him almost as much (and in some cases with greater intensity) as I did back in the twenties. This, I suppose, may be interpreted in different ways: (1) that I have not developed mentally since college days, (2) that Mencken is as shrewd an inconoclast as we ever had, and that he writes with understatement (which I believe) truths which we as a people refuse to recognize. Read for instance what he says about the late William Jennings Bryan, about government as practiced in these United States, "The Sahara of the Bozart," and most of the rest of this volume and you will gradually become aware that Mencken has been, and still is, a vastly underrated fellow. I venture to say that when things are summed up after Washington is but a heap of radioactive particles Mencken will tower over most of his fellows as Shaw does over the anaemic purveyors of prose in England. I have made this a bedside book all summer and have read every page with amusement and with many chuckles. It is too easy to dismiss Mencken as the author of The American Language. He is much more than that: a social critic of real stature.

The most important book by far that I have read since Owen Lattimore's TheSituation in China is Paul Blanshard's American Freedom and Catholic Power (Beacon Press, Boston, 1949). I have not yet finished the last three chapters but I have read enough to feel very strongly that this is a book that should be read by both Catholics and Protestants alike. It is a forthright and hard-hitting book, most careful in its statements, and points out to the democratic United States the dangers of a strong and militant authoritarian force which allows no freedom of thought within its ranks, and which has enormous political power in these United States.

Paul Blanshard is a trained investigator and this book is a monument of scrupulous documentation and has been checked and rechecked by a distinguished group of scholars both Catholic and Protestant.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

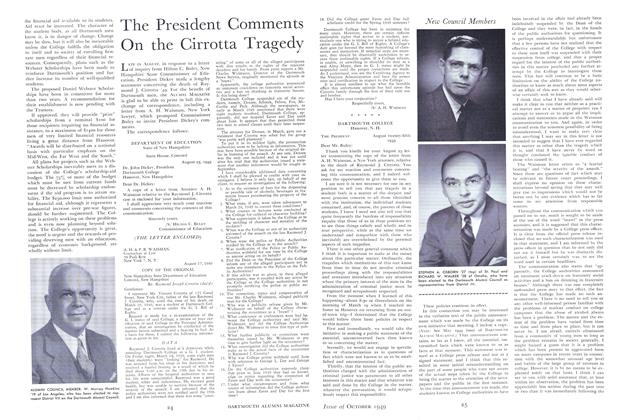

ArticleThe President Comments On the Cirrotta Tragedy

October 1949 By /S/ John S. Dickey -

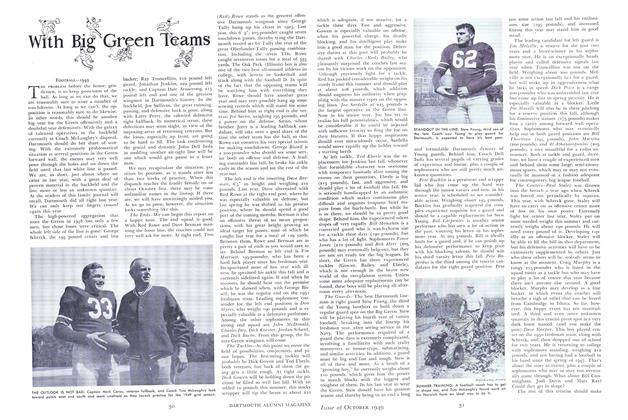

Sports

SportsFOOTBALL—1949

October 1949 By Francis E. Merrill '26 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Seeks Growth of Its Scholarship Funds

October 1949 By ROBERT L. ALLEN '45 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

October 1949 By ERNEST H. EARI.EY, DONALD L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926

October 1949 By E. PAUL VENNEMAN, HERBERT F. DARLING, ROBERT M. STOPFORD -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

October 1949 By TRUMAN T. METZEL, COLIN C. STEWART, 3rd, JULIUS A. RIPPEL

HERBERT F. WEST '22

-

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

November 1936 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Books

BooksTHE LAST TIME I SAW THEM,

August 1946 By Herbert F. West '22 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

October 1946 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

January 1954 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

April 1956 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Books

BooksPREPOSTEROUS PAPA.

January 1960 By HERBERT F. WEST '22

Article

-

Article

ArticleALUMNI NOTES

AUGUST, 1927 -

Article

ArticleCollege Adds 84 Acres

October 1956 -

Article

ArticleTHE DARTMOUTH CHANGES HANDS

MARCH 1930 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Article

ArticleTHE GENUS EMERITUS

January 1962 By ALLEN R. FOLEY '20 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

November, 1930 By Craig Thorn, Jr. -

Article

ArticleObligations of Alumni

July 1953 By ROBERT PROCTOR '19