MR. CLARENCE G. MCDAVITT '00, President of the Dartmouth Athletic Council, suggests the following books which have recently interested him. These are:

1. Are Trade Unions Obstructive?' (1935). Has to do with trade unions in England; prepared under a joint editorship; really impartial. Employer's point of view with regard to thirteen industries followed in each case by trade union point of view.

2. Why We Don't Like People. (1933). By Colgate University professor of psychology. Excellent medicine for one with anything approaching a "swell head."

3. The White Hills. (1935) By Cornelius Weygandt. Delightful for one-who gets a thrill out of even a motor trip through the White Mountains.

4- Of Human Bondage. By W. Somerset Maugham. (You see how far behind I am in modern fiction, but better late than never.)

5. Industry in England. By H. DeB. Gibbens. First published about forty years ago. In fact it was a textbook in economics while I was an undergraduate. Very interesting for one who has even a slight knowledge of the general subject.

Inasmuch as I expect to be far from Hanover when this copy has to be in, I am writing it before the Christmas holidays, and save where I quote from letters I shall write briefly of a few books, some of which are advance books from England, which may not be published here for some time, so that I trust the notices will prove timely.

The Last Puritan, by George Santayana. Constable, London.

I finished this book the last of November, and was not surprised at that time to learn that it was to be the January choice of the American Book-of-the-Month Club. It is one of their better selections.

Mr. Santayana is one of the wisest of living philosophers. There is no contemporary more sure in the detection of metaphysical quackery, and his puncturing of the overblown theories of such pundits as Bergson, and certain German philosophers, is intellectual sport of the first degree. Famous for his Lifeof Reason, for his charming essays, for his sonnets, for his final statement of his philosophic position in Realm of Essence, and for his style, his long delayed novel has been eagerly watched for by discriminating critics.

Considering the fact that Santayana is not a novelist, The LastPuritan is a very deft job, but in spite of the wide panorama of a Boston and European society which it depicts, in spite of its wise and penetrating study of the Puritan type in Mrs. Alden, and in spite of its fine writing, I cannot help but feel that it is a highly artificial performance. The author himself admits its artifice in the epilogue when he writes: "Fiction is poetry, poetry is inspiration, and every word should come from the poet's heart, not out of the mouths of other people (that is to say, the characters)." The characters, he says, "are creatures of the imagination." I have said that the novel is artificial, but perhaps when one suddenly comes upon a classical novel, that is, one written from the point of view of Plato's lon, so rare is the experience in these romantic days, that one doesn't recognize a purely literary novel when he sees it. Even so the story is only relatively artificial, for Mrs. Alden is human, Jim Darnley and his mother ring true, though Peter and Mario seem unreal to me. Oliver is a finely drawn character . . . • the last Puritan! The book deserves a wide audience. It is mellow and highly sophisticated; it is written with an urbanity which should shame our Thomas Wolffs and William Faulkners; it contains many shrewd and intelligent observations on life. It is a memoir in the form of a novel. There is, I might add, an unhealthy pallor about the book, a curious corrupt quality that one might associate with orchids. This air of decay in the novel may be a sign of over-cultivation in an ivory tower heated like a conservatory. A slightly decadent Greek atmosphere doesn't mix too well with a New England setting. However, this is a book that must be read.

Night Pieces, by Thomas Burke, Constable, 1935.

There are few people who know London as well as Thomas Burke. This is the latest collection of Mr. Burke's eerie and macabre short stories. Not all of them quite come off, but several are excellent.

Poor John Fitch, by Thomas Boyd. Put nams, 1935.

The late M. Boyd had just finished this manuscript, without complete revision, when he died, and his wife Ruth Fitch Boyd gave it the finishing touches and saw it through the press. It is, without question, Mr. Boyd's finest biography. With a touch of juixoticism, inherent in his character, the author resuscitates and brings to life the eccentric and tragic inventor of the first steamboat. There is no doubt whatever that Fitch designed the first steam driven boat long before Robert Fulton's Clermont turned its paddle wheels on the Hudson, and yet ask any schoolboy, and most adults, who it was who invented the first steamboat, and their invariable answer will be Fulton. The reasons for this Mr. Boyd makes clear. I recommend this book, and especially to those readers who like soundly documented and honest biography.

My First Seventy Years, by Florentine Scholle Sutro. Roerich Museum Press, N. v., 1935.

Mrs. Sutro reveals herself as an alert, courageous, and vital personality, who at seventy wrote a record of her life for her own pleasure. After her husband's death in 1931, she decided to go to Russia, and her observations made at times under discomforts that would have discouraged many a younger person, resulted in the most interesting chapter in the book. Mrs. Sutro has been active ever since her girlhood, in social service work, birth control, and in many other intelligent causes. She has travelled often and widely; she has known many people, simple and great, and has been as interested in the one as in the other.

It is regretable that Mrs. Sutro has not given us more reflections on what she has seen, or in other words, has not given us more of herself, and less of her diary. The often bare record of places visited and people met is not enough to intrigue a reader for 452 pages. Had the number of events been cut down, and the significance of things seen been elaborated more, a far better book would have resulted. Inasmuch as Mrs. Sutro is-not a professional writer it would be captious to point out infelicities of phrase, etc., but it is pertinent to say that the book should have been more carefully proof read: Skansen for Swanska, etc.

Paul Bowerman '19, for many years consular representative abroad, sends me a list of recent reading: Laughing Boy by Oliver LaFarge; The Analects of Confucius; Cheri by Colette; An Examen of Witches by Henry Boguet; Wordsworth's Prelude; Letters by William Cowper (the stricken deer); and Mrs. Letitia Pilkington's Memoirs. This seems to me to be an unusually good list.

Another note from E. Gordon Bill, Dean of the Faculty, says: "that if you wish to put an edge on your mental processes, try In Seanch of Truth by E. T. Bell. This book, written by a mathematician and hence with clarity, debunks many current theories and analyses with the precision of the Princeton blockers."

The last book that Natt Emerson, enthusiastic and discriminating reader, kindly and generously (as was his custom) recommended to me was Lin Yutang's MyCountry and My People. After reading it I can see clearly that its philosophy reflected the serenity, the courage, and cheerfulness that characterized Natt Emerson's last days. He was most earnest about the high quality of this book, and after taking his advice and reading it, I can only say, that in my opinion, he was absolutely right. It is the best and most profound book I have ever read on China, and it seems to me essential in the understanding of Chinese life, literature, manners, philosophy, history and their general attitude toward life. Do read this book.

I should like to believe that there are a great many alumni, who in their reading and collecting, follow the practice of Robert F. Estabrook 'O2, who is Vice President of the New England Telephone and Telegraph Company, and who was introduced to me by Clarence G. McDavitt. Mr. Estabrook liked Greek in college, and still likes it after thirty-five years. Some months ago he began going through a hundred or more book catalogues, and in the last six months has acquired over seventy-five volumes of the first English translations of the Greek classics published in the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries. This led Mr. Estabrook to a renewed study of Greek authors and their translators, of their times and historical background, as well as to collecting some of the original Greek texts. He has done this without paying any fancy prices and he writes: "there is quite a kick in acquiring for a dollar or two a nice, old, usually worn and marked up leather bound volume that must have been through the hands of many owners in the two to. four hundred years it has survived." Mr. Estabrook is the pure collector who collects because he loves good books. He is one after my own heart. He balances this reading with the books of modern scientists such.as Millikan, Eddington, Jeans, Shapley, DeSitter, Soddy, and Hudson; with such biographies as Catherine the Great, Queen Elizabeth, Goethe, etc. Many thanks to Mr. Estabrook for his fine letter.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleGRADUS AD PARNASSUM

February 1936 -

Article

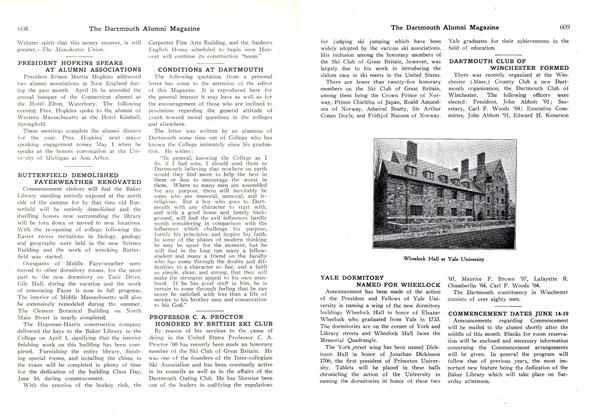

ArticleDartmouth's Olympic Skiers

February 1936 By Robert P. Fuller, '37 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1911

February 1936 By Prof. Nathaniel G. Burleigh -

Article

ArticleEdwin Brant Frost, Class of 1886

February 1936 By Arthur Fairbanks '86 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1934

February 1936 By Martin J. Dyer, Jr. -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1908

February 1936 By L. W. Griswold

Herbert F. West '22

-

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

December 1934 By Herbert F. West '22 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

October 1938 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Books

BooksNO SHIP MAY SAIL

June 1942 By Herbert F. West '22 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

January 1947 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

December 1953 By Herbert F. West '22 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

May 1955 By HERBERT F. WEST '22