The Selective Process, Reaching Its Climax This Month, Is Discussed by the Alumni Council's Admissions Chairman

IN THE TWENTY-SEVEN years since Dartmouth inaugurated its Selective Process of Admission some 17,000 of an estimated 70,000 secondary school hopefuls have scaled the heights to matriculation on the campus of Eleazar, and this group today represents approximately 70 per cent of the Dartmouth alumni body.

The policy of selective admission, acclaimed by leading educators as the dawn of a new era in higher education, was headlined by the national press as the procreativie medium for an "aristocracy of brains." To the alumni at large, however, the majority of whom remembered the days of the bearded, sweat shirt culture, the new policy marked the end of rugged individualism, and the sacrifice of brawn for brains.

Dire predictions were sounded by alumni groups throughout the country. It was not skepticism as to the desirability of the new process; it reflected firm conviction that the "Big Green" athletic teams would soon be as extinct as the dodo, to give way to a new generation of erudite gladiators of the chess board.

Most opportunely the "Big Green" teams created a diversion in 1924 and 1925 and temporarily at least allayed the fears and quieted the unrest. In fact, in the wake of the national recognition accorded the great 1925 football team even the more skeptical of the alumni critics were converted when they learned that the composite scholastic average of this team was just under Phi Beta Kappa standing. The doubters of yesterday became vociferously articulate in heralding the arrival of a new superman on the Dartmouth campus, combining brawn with brains.

The normal ebb and flow of athletic successes in the late twenties and early thirties ties, however, tempered alumni enthusiasm, and when the gridiron machine of the "Big Green" went into reverse, the witch hunt was on, and the Selective Process caught the full vent of alumni reaction from coast to coast.

Discrimination against athletes in favor of the "greasy grind" was the general theme of unenlightened criticism. The capacity of the coaches had been established in major competition, contended the critics, and they couldn't be expected to build a winning team from anemic and round-shouldered bibliophiles.

Suggested changes in admissions policy were gratuitously offered by associations and clubs from all parts of the country, usually varying in caustic intensity directly with the distance of the group from Hanover. Hold to your standards for general admissions if you must, they importuned, but lower the academic sights for at least a few hairy chested he-men who, although lacking the Phi Beta Kappa potential, would maintain a reasonable competitive stature for the Green.

Father Time seemingly takes care of all things, and on the Dartmouth campus, after twenty-seven years of operation, the results of the high degree of selection in admissions practised by the College has justified to the preponderant majority of the alumni both the concept and the means of the Selective Process.

ALUMNI PARTICIPATION INCREASES

The participation by alumni in the procedures of selective admissions has increased about five-fold both in depth and breadth over the period of its operation. At the start officers of alumni'associations and clubs were called upon to act as general chairmen of their respective geographical areas to appoint and supervise the activities of local interviewing committees, usually composed of three alumni. These committees; making the contact with applicants for admission within their local communities, and on the basis of a personal interview evaluating competitively the overall desirability of each, have played an increasingly important role in establishing and maintaining a personalized public relations front for the college.

In 1923 a scant two hundred alumni, with the heavier concentration in New England and the Middle Atlantic states, entered their novitiate in the admissions field. For the current admissions year, under the sponsorship and active direction of twenty-four members of the Alumni Council, over four hundred alumni interview- ing committees, with a total membership aggregating over twelve hundred men, are interviewing, advising, and evaluating the general qualifications of close to five thousand applicants from coast to coast.

Through rotation in the membership of these committees an increasing number of alumni are sharing in the administrative function and acquiring both a broader understanding of the problems inherent in selection and a greater appreciation of its intrinsic merit.

Understanding and appreciation of Dartmouth's Selective Process are growing steadily among all the alumni, but some points of miscomprehension continue to exist. It may be helpful to consider those which crop up most frequently, and in do- ing so the following question-and-answer form will be used.

QUESTION—In view of the fact thatsome boys rated highly by the alumni interviewing committees are not admittedand other boys rated relatively lowerwithin the group are accepted, just howmuch weight does the College give tothese alumni recommendations?

The form No. 6, known as the Alumni Council Rating, which is processed by the alumni interviewing committee, is only one of the six forms required for each applicant. While its value and relative importance to the admissions officers in the determination of acceptance or rejection of a candidate have increased over the years, it must be realistically weighted in its proper relationship to the other five forms in the overall evaluation of the applicant. It reflects the personality, depth and breadth of interest, qualities of leadership, and the extracurricular interests and degree of success therein of the individual. These qualities, which although highly significant in the measure of desirability, must yield to the factors of low aptitude and of scholastic performance below the minimum competitive level, as documented in the confidential data recorded in forms No. 4 and No. 5 by the headmaster of the secondary school.

The records of the past ten years establish that a very substantial majority of the applicants accepted for admission have been evaluated by alumni interviewing committees as either highly desirable or desirable. Alumni Councilors, making an impartial but critical review of the cases of applicants from their geographical areas who were not accepted, although favorably rated by the interviewing committee, have invariably found a yellow or red light posted by the secondary school headmaster, indicating with convincing documentation either scholastic deficiencies or, more important, lack of capacity to meet the competitive standards of performance.

Once or twice during the admissions year it is not unusual for the wires to hum and the sparks to fly between the Admissions Office and an Alumni Councilor when the latter challenges the decision to admit an applicant who has been rated undesirable by an alumni committee. Here again, in a judgmental determination, carefully considered and based on an objective evaluation of the six completed forms in this applicant's file, the negative implication of the alumni rating, unless it frankly records fundamental and important weaknesses in personality or character traits, would ordinarily not counterbalance the weight of the considerations of the other five admissions forms, if highly favorable.

In short, the alumni interview plays an important supplementary but usually not independently determining factor in the overall evaluation of the applicant. This is both logical and natural, since in the majority of cases the interviewing committee has no previous knowledge of or acquaintance with the applicant, and its qualitative rating is based on the impressions and findings of one interview of less than an hour. The "school forms," No. 4 and No. 5, on the other hand, are supported both by performance records and by the personal observations of experienced educators over a period of four years.

QUESTION—Isn't the Selective Processsupposed to give preference to sons ofalumni, and if so, just what does this preference meant

This question, so frequently asked, stems from the present No. i problem of selective admissions, i.e. the non-acceptance of an alumni son. It is recognized as the "top" problem not alone at Dartmouth, but in greater or lesser degree at all of the colleges and universities practising a high degree of selection in their admissions, including Amherst, Yale, Harvard, Williams, Princeton and an increasing number of others. It results inevitably in every competitive situation wherein the number of applicants far exceeds the enrollment limitations.

Although the admissions policies of Dartmouth and Princeton were independently conceived in the early 1920's and have been administered with a minimum of inter-institutional collaboration over the years, in drawing conclusions as to the desirability or value of the operation of this system at either or both of these institutions, it is interesting to refer briefly to the experience records of each.

A special committee of five alumni was appointed by the Graduate Council of Princeton in October, 1947 to review the current admissions policy and its attendant problems, and to publicize the findings to the alumni body "that it may be fully informed and appreciative of one of the most serious problems facing the University."

In the findings of this committee, published in May, 1948, it is significant that among the three most serious problems are the demands that more Princeton sons be admitted,—and more athletes.

On the first, Princeton sons, the committee considers that "fairness to those who are denied as well as to the other (non-alumni) applicants prevents greater preference."

Continuing, the committee finds that it is undoubtedly true that, other factorsbeing equal, a Princeton son gets the preference, but if a Princeton son does not show a scholastic aptitude, based on his school performance and on the College Entrance Board scholastic aptitude tests, which indicates that he can successfully complete a Princeton education, it would be neither a kindness to him and his parents nor fair to other, better qualified applicants, to admit him. The same applies to a case where, though tests are passed, the recommendation of the principal or headmaster is unsatisfactory. Undoubtedly Princeton still admits cases which must be classified as 'marginal' ones in regard to its standard of admission; but with the pressure of so many applicants, it is today impossible, in fairness to all concerned, to accept as many 'marginal' cases as in less crowded times."

In conclusion the committee records itself as "unanimously of the opinion that Princeton sons are now given as great preference as can be soundly justified."

QUESTION—Turning back to Dartmouth, what is the present status ofalumni sons in our admissions picture?

Because of the abnormalities and disruptions of the war and immediate postplicants war years in their effect on college matriculations and continuity of study any conclusions drawn from the statistics of the Dartmouth classes of "42 to '49, inclusive, must be regarded as unreliable and spotty.

From the first two classes of the postG. I. period, 1951 and 1952, however, entering in 1947 and 1948, respectively, a pattern can be drawn with respect to die competitive status of sons of alumni that may be considered predictive, at least of the years immediately ahead.

From a total of approximately 6000 applicants for the Class of 1951, which incidentally now looks to be the postwar peak in total number of applicants, 650 men, representing one out of nine, or 11%, were accepted. Included in the 6000 total were 250 sons of alumni of whom 144, or 58%, were accepted for admission, and 139 actually matriculated.

The Class of 1952 matriculated 718 men, or 14% of the total of just over 5000 applicants, a ratio of one to seven. Of the 256 sons of alumni who were included in the total, 138, or 54%, were accepted for admission, but of these only 117 elected to matriculate.

A substantial number of these sons of alumni qualified at the top level of competition without the benefit or need of group preference. The balance, running to possibly 40% of the total, ranked at the marginal competitive level, and all other qualifications being equal, were accepted under alumni preference over several hundred non-alumni applicants at about the same level.

The composite figures for the two classes, 1951 and 1952, very effectively demonstrate the weight of the preference given to sons of alumni. Whereas in the total of x 1,000 applicants only one out of eight, or 12.5% were accepted, roughly 14 out of 25, or 56%, the sons of alumni were selected. There are undoubtedly some who will argue that this percentage of sons of alumni should be even larger, that any alumni son who has a fighting chance of scholastic survival should be given a trial opportunity; in short that Dartmouth should foster its kin and, if necessary, adjust its educational requirements and objectives to the capabilities of the marginal group. The Dartmouth Alumni Council considered that sentiment a year ago last June and went on record as follows: "Dartmouth has always been an alumni college, but the College has grown and changed since our day. Due to the increase in the number of applicants for admission to the College and to the greatly increased numbers of Dartmouth sons applying for admission, this committee feels that Dartmouth fathers and their sons must recognize that from here on the sons will have to meet keener competition for selection. The Selective Process, in other words, which has always given preference to Dartmouth sons, should continue to do so but the sons will have to meet the competition of that year, both in regard to academic and other factors of the process. We hope and believe that Dartmouth sons should always receive preference, other things being equal or nearly equal."

QUESTION—As measured by academicperformance, how do the sons of alumnishape up competitively within their classgroups?

To those who may still challenge Dartmouth leadership in its concept of the fundamental purpose of the college as a national institution of higher learning, particularly with respect to the competitive selection of alumni sons, the academic performance record of this group should be both enlightening and convincing.

For such analysis, alumni sons fall into two general groups,—those who qualify on merit at the top competitive level, and the larger group who are admitted under the operation of alumni preference in the lower to marginal competition. Of the first group, who qualified on their own, the records indicate that with few exceptions such boys maintain their top competitive standing scholastically and more than pull their weight in undergraduate leadership and in the extracurricular life of the college.

In the other group of alumni sons, those admitted under preference, the validity of secondary school scholastic standing and standard aptitude tests, as a basic factor in selection, is strikingly demonstrated by the statistics of the Class of 1951, showing the proportion of this group in scholastic difficulty for the first year to be double the proportion of the class as a whole. In other words, it is the alumni son admitted under preference who is weighting the lower quarter of the class and experiencing the greatest difficulty in meeting the competitive standards for scholastic survival.

QUESTION— What effect has Dartmouth's highly selective system of admissions had on undergraduate scholasticmortality?

In the answer to this question is found perhaps the most convincing endorsement of and justification for the Selective Process.

For the period from 1910 through 1922 the mortality, or attrition, of the Dartmouth classes was approximately 40%; or conversely, only 6 out of 10 who matriculated went through to graduation. While this figure includes withdrawals for health, financial, disciplinary and other non-academic reasons, the major cause of attrition, estimated at 85% of the total, was academic failure.

Over the first eighteen years under the Selective Process to 1940 this mortality decreased to roughly 25%. During the succeeding eight years the personnel statistics of the war and immediate post-war period were so scrambled because of the dislocations of military service that here again, for the classes of 1942 to 1949 inclusive, comparative data is unreliable.

Starting anew with the Class of 1951 as a norm of reasonable expectancy over the next decade, subject to continued world peace, a further and most impressive decrease is recorded. At the opening of college in September, 1948, 616 of the original class of 654 started their sophomore year on the Dartmouth campus. The attrition of 38 men from all causes, represents a new low of 5.8%. While this is for one year only, it is the year by far of greatest mortality, since both Dartmouth and national statistics indicate that the mortality of freshman year usually approximates that of the aggregate of the succeeding three years.

While any superficial conclusion based on the experience of one year is in the realm of statistical acrobatics, the writer on his own responsibility, and probably with the official disapproval of the administrative officers, will venture the prediction that this new low of 5.8% for the freshman year of the Class of 1951 may be indicative of a total mortality of 12% to 15% for the full four years.

QUESTION—Is this progressive reduction in undergraduate scholastic mortality,as experienced under the selective system atDartmouth, reflected in the comparablefigures of the colleges throughout the country?

Emphatically, no! For authority reference is made to the report titled Behin'd theAcademic Curtain by Dr. Archibald Macintosh, vice president of Haverford College, a summary of which was featured in The New York Times of September 5, 1948. This educator, an authority in his field for the past twenty years, conducted a two-year study of the 655 liberal arts institutions of the country. In his report he reveals some startling statistics on college mortality and in his conclusions points up the basic reasons for the heavy attrition in the American colleges of today. Academic failure, as might be expected, was the principal cause of student mortality, with financial reasons next in importance. He blames the Admissions Director in part for the large number of student failures and points out that if greater effort were made to select students who could successfully meet academic requirements, the loss from academic failure would be considerably lowered.

Classifying the institutions according to size, he points out that the mortality figure is somewhat dependent upon the size of the institution and other factors. In the published statistics he records a mortality high of 61.1% for co-educational institutions of over 1000, with a low of 37% in men's colleges of over 1000 students. Women's colleges range from 45% for those of under 1000 enrollment to 50% for those of over 1000.

Dr. Macintosh, commenting on the low figure of 37% for men's colleges of over 1000, explains that this figure is influenced by the high degree of selection practised by such colleges as Amherst, Colgate, Dartmouth, Harvard, Lehigh, Princeton, Union, and others where many marginal students are screened out in the selection. He urges the colleges to examine their policies to determine the causes of such tremendous attrition and to consider the overall effect on the individual in cases of failure, resulting in frustration, loss of self-confidence, and a futile groping for direction. In conclusion he stresses the immeasurable but tremendous loss in human potential.

The columnist of The New York Times who write the feature article comments that "too many persons, educators as well as parents, are more concerned with the admission of students into college than keeping them there once they are enrolled. It is appalling to find that half of the students who enter our colleges and universities this year will fail to complete their courses" and commends the Macintosh report "as a thoughtful, provocative analysis of a highly essential although commonly neglected phase of college life."

QUESTION—What is the grist of theDartmouth mill?

Looking again to the most recent classes of the post-G.I. period we find that in academic potential, as measured by the standard and time tested psychological examination of the American Council on Education, utilized by 373 colleges as a required examination for all freshmen, the upper half of the Class of 1951 equalled the top 18 per cent of the national norm based on the examinations of over 70,000 students matriculating at the 373 colleges in the fall of 1941.

The academic average for the entire class for the full freshman year was 2.2 or between a "B" and a "C" average.

While the complete statistics for the first semester for the Class of 1952 have not been completed for official release, the Dean of Freshman is the authority for the statement that the average for the entire class will probably exceed even the high average of its predecessor, 1951. It is also a matter of record that in the American Council of Education examination this year the upper 50% of 1952 attained the composite rank equalled by the top 42% of the Class of

QUESTION—In selecting its freshmenis Dartmouth now turning away from itstraditional emphasis on the all-round boyand favoring the applicant of "Phi Bete"ability?

To the contrary, the emphasis is very definitely on the breadth and depth of the allround qualifications of the individual. The now rapidly fading myth that under the present selective admissions only the "greasy grind" would qualify should be finally laid to rest, factually refuted, after a brief analysis of the diversified accomplishment of the present undergraduate body. Because of the availability of more complete non-academic statistics covering the past two years reference -is again made to the last two entering classes—1951 and 1952-

In athletic potential, qualities of leadership, and outstanding participation in extracurricular activities the Class of 1952 again appears to have a slight edge on its predecessor, which a year ago was deservedly acclaimed as one of the strongest classes, if not the strongest, of Dartmouth history in all-round potential.

Of the 718 freshmen who matriculated in the Class of 1952, 268 made their varsity football letters in their respective secondary schools. Thirty were football captains, with other captaincies numbering 18 in baseball, 32 in basketball, 6 in hockey, 13 in track, 11 in tennis, and 9 in swimming,—a total of 133 team captains.

Of the 119 freshman athletes already considered by the coaches as good varsity pros, pects in their respective sports, eleven attained a first-semester average in the Phi Beta Kappa range—between 3.0 and 4,0, The semester average for the entire group of 119 was 2.04, which is on the sunny side of a C average, with Das the passing grade.

Balancing the breadth and depth of the Class of 1952 in athletic participation is the equally impressive record of leadership honors and of accomplishment in literary, dramatic, and musical activities shared by approximately three hundred of its members. These include among others 142 boys who were presidents of their secondary school classes, 45 who were presidents of student government, 39 editors-in-chief of school newspapers or magazines, and 34 yearbook editors.

QUESTION— What can alumni do constructively with regard to Dartmouth admissions?

As noted above, something like a thousand alumni are now actively engaged in assisting the Selective Process through their interviewing work in committees all over the United States and abroad. This involves many hours of work on the part of people whose time could not be bought for many scores of thousands of dollars. Their service is more valuable than ever in the present competition in which choices must be made between excellently qualified candidates who cannot be admitted and slightly better ones who can.

Dartmouth men who have sons who are prospective candidates for admission should have the boys get in touch with the Office of Admissions during the first year in secondary school, file their preliminary applications, be assured that their school program is wisely designed, and acquire a sound perspective of what will be necessary qualitatively to be a strong candidate for admission four years hence.

Dartmouth men who hear rumors about actions' of the Committee on Admissions which do not make sense should ascertain the facts before joining in the further dissemination of die rumors. Careless talk hurts the College.

Finally, this is no time to be complacent about Dartmouth's competitive position in attracting the best candidates. True, Dartmouth's applicants have outnumbered available places six, eight, ten to one. But the same thing has been happening in other colleges and universities with which Dartmouth is traditionally associated. Moreover, we are at a serious disadvantage com' pared to some of them with regard to available scholarships. Each year we lose some excellent men for whom scholarship aid is not a factor. Far more important than these, however, are the outstanding boys of whom we do not hear. It is safe to say that within the reach of every Dartmouth man there is at least one outstandingly fine college candidate who will not apply to Dartmouth. Of course, we can't get them all: but what Dartmouth man will be content with our getting only our share?

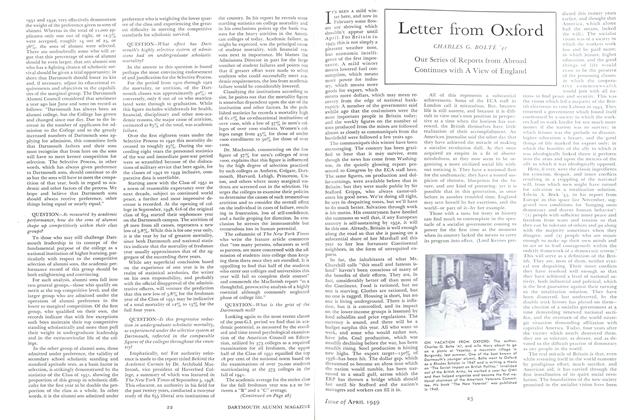

AT THE LAST ALUMNI COUNCIL MEETING, H. Clifford Bean '16 (left), chairman of the Council's Com- mittee on Admissions and Schools and author of this article, talks things over with President Dickey.

Mr. Bean, chairman of the AlumniCouncil's important Committee on Admissions and Schools, gave such an excellent report at the last meeting of the Council that the editors asked him if he wouldn'trecast his remarks in the form of an ALUMNI MAGAZINE article for the benefit of allDartmouth men. We are particularly gladto publish it this month, when the subjectof admissions is so timely. Ever since thestart of the Selective Process, Mr. Bean hasbeen a leader in interviewing applicantsfrom the Boston area, and no Dartmouthalumnus, it is safe to say, knows moreabout the general admissions picture thanhe.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHE ARCTIC

April 1949 By TREVOR LLOYD, -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorLetter from Oxford

April 1949 By CHARLES G. BOLTE '41 -

Class Notes

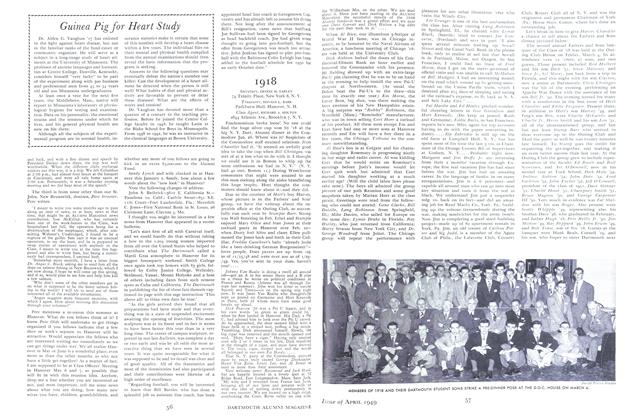

Class Notes1918

April 1949 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Article

ArticleDeaths

April 1949 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

April 1949 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, EDWIN C. CHINLUND, GEORGE B. REDDING -

Class Notes

Class Notes1914

April 1949 By DR. WALLACE H. DRAKE, RUFUS L. SISSON JR., JOHN F. COiNNERS