The Dartmouth Spirit

To THE EDITOR:

Returning to Boston after an absence of some years in South America to attend the 25th reunion of my class at Hanover I showed Edgar O. Achorn, a well known attorney of Boston, the program of the annual dinner of the D. A. A. of Boston, the winter of 1915. "How is it," querried Edgar, at that time President of the Bowdoin alumni association of Boston, "that you Dartmouth men always have such a large percentage of your alumni present at your annual meetings?" I ascribed it to the Dartmouth Spirit but was unable to give a very lucid definition of what that was. Returning from South America 25 years later to attend the 50th reunion of my class at Hanover, June 1940, I was amazed at the change in the plant of the College that had taken place under the administration of President Hopkins. The 25th and the 50th reunions were the first I had ever attended. The change at the 25th reunion under President Tucker was great. I regret that I never had the pleasure to meet him. While in Philadelphia a month later, July 1940, I was invited to attend the meeting of the Dartmouth alumni of that city at the Yale club. The percentage of attendance at the Dartmouth meetings was uniformly larger than the Yale meetings.

Well what is the Dartmouth Spirit? It stems from Wheelock, the founder of Dartmouth. He was a positive, persistent missionary of the Gospel among the Indians, the aborgines of North America. The man who could wangle $50,000 from the Earl of Dartmouth and others was not just a run-of-the-mine missionary. Dartmouth was the last of the preRevolutionary colleges. As Prof. Leon B. Richardson states it, "Alone among the preRevolutionary colleges of America, Dartmouth owes its existence to the dominating force of a single personality." The odyssey of Wheelock and his Indian School which later became Dartmouth College is unique in the founding of American colleges. President Tucker called it "The great educational romance of the 18th century."

In the early years the Dartmouth Spirit was embodied in Daniel Webster and Thaddeus Stevens. In all probability had not these two giants gone to Dartmouth their latent faculties might never have been developed. But they did go and we now have a united Republic as a consequence. Justice Stafford in his address at the celebration of the Sesquicentennial Anniversary of Dartmouth contrasted the public services of Webster and Stevens. Of the former it was said that his voice was heard in the deep roar of the union guns from Sumter to Appomattox. Stevens was a native of Vermont. Graduating from Dartmouth in 1814, he went to Pennsylvania where after being admitted to the bar he began the practice of law in Gettysburg and later moved to Lancaster, Pa. He was elected to the 31st Congress in 1848 and to the 32nd Congress in 1850, retiring from Congress at the close of the 32nd term. On the formation of the Republican Party he was elected to the House in 1858. From December 1859, Stevens then 70 years old, for nine years ruled the House of Representatives with a rod of iron He hated slavery all his life. Living on the border of the slave power, he saw all its horror. Shortly before his death he learned that persons of color were not permitted burial in the cemetery where he owned a lot. He at once disposed of it and bought a lot in Schreiner's Cemetery, Lancaster, where he now lies. There the gates were opened unrestrictedly to all. When he died Stevens was regarded as the ablest lawyer in the States. Consciously or unconsciously, Stevens walked in the footsteps of Wheelock.

The Dartmouth spirit has had its wholesome influence on all the college sports, on its songs, on the carnival, in short on all that pertains to the college life in Hanover. The missionary spirit: The word "mission" means a sending forth. Every son of Dartmouth when he receives his degree goes forth with a mission in life—that which he is destined or fitted to do, his calling. Whether he is conscious of it or not, the Dartmouth Spirit will leave its impress on his career.

Boston, Mass.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHE ARCTIC

April 1949 By TREVOR LLOYD, -

Article

ArticleConcerning Admissions

April 1949 By H. CLIFFORD BEAN '16 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorLetter from Oxford

April 1949 By CHARLES G. BOLTE '41 -

Class Notes

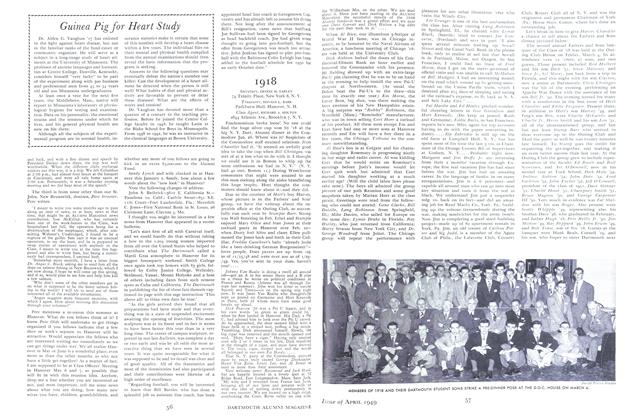

Class Notes1918

April 1949 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Article

ArticleDeaths

April 1949 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

April 1949 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, EDWIN C. CHINLUND, GEORGE B. REDDING

Letters to the Editor

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLETTERS FROM THE ALUMNI

February 1916 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

October 1941 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorA Matter of Accuracy

May 1950 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLETTERS TO THE EDITOR

FEBRUARY 1964 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

MARCH 1973 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorA Fluxus Ruckus

December 1992