Dartmouth's Artist-in-Residence, Steadily Growing in Stature as American Painter, Is Stimulus To An Expanding Art Colony In Both College and Community

EVERY man wants to create something beautiful and enduring but few ever do owing to the lack of a deep enough desire or the will to keep going under adverse conditions and after repeated failures. The artist who is gripped by the daemon just simply has to paint. Witness Gauguin who sacrificed wealth, social position, respectability, family and security, in order to paint. We need not look as far as France or the South Seas for such a painter; one who was born to paint is here at Dartmouth in the person of Paul Sample. I mean one who paid the price of hard work and many lean years before he received recognition and before he became the great painter he is. But few fortunate ones have known his reward—the ecstasy of now and then creating a flash of imperishable beauty which will endure as long as his painting lasts. He considers this reward enough.

It was not long after the first world war that Paul Sample felt a strong resentment (still not dead) against our commercial civilization and against its crass and vulgar standards and values. He had seen his father, an expert civil engineer, thorough and well-trained, slip from professional and material importance, and he had seen men of less ability take his place and eventually make a great deal of money. Early he sensed the system was cruel and unjust. We hated our success measured in terms of dollars, our feeling of the necessity of keepIng up with the Joneses, our standardization, our corruption to which we are singularly indifferent as a people, our high-pressure salesmanship, our vulgarization of most art to Hollywood standards. There was nothing—there is nothing—soft in his resentment. Painting was a way out of this for Sample, so he decided after a long and critical illness to become a serious professional painter. Quite a decision for a man in his late twenties to make, and to stick to.

All great painters have integrity, though not all painters with integrity become great painters. When Sample, who has both honesty and integrity, and who never stops experimenting and improving his technique, who is never satisfied except with his very best, succeeds in merging at one time his judgment, his taste, h feeling for order and his mastery of his medium, then a great picture is born. To mention a few which will stand up under the severest tests: "Delirium is Our Best Deceiver," which I will discuss later on, "Nora Kaye," owned by Mrs. Paul Sample, "The Return," owned by Mr. Goshhorn, "The Hunters" (sometimes known as "The Fox Hunt") owned by Mr. Lowenthal, and "Southbound through Lewiston" (Vermont), owned by the Abbott Laboratories. There are others.

Sanford Ross, a mutual friend and himself a painter of distinction, pointed out to me how Sample got perspective in his wellknown and oft-reproduced picture "The Hunters" by placing the figures of the hunters in the pattern he did. Study this picture sometime and note, too, that the hunters leave no footprints which would have marred Sample's idea of simplicity in form and color for this particular picture.

Paul Sample thinks that his first important picture, together with his painting of the Los Angeles hospital ward now hanging in his studio, is "Church Supper," painted at Willoughby Lake, Vermont in 1933. Now in the Springfield, Massachusetts, Museum, it is an arrangement of many figures, his first venture into this genre. His wife Sylvia writes of this stage in his development as follows: "It is genre painting which now occupies him espe- cially. People—human beings living their lives—workmen and their families—whether in industry in the city or in farm life in rural areas—not for any political or moral propaganda but just to reveal them and through them himself in sympathy with them as they really are." This surely is one reason why Paul Sample is not interested in portraiture though he can paint excellent portraits as witness his "Will Bond," "Nathaniel Goodrich," and "E. Gordon Bill." Asked recently if he still considered himself primarily a genre painter, he said that he did.

Paul Sample was born in Louisville, Kentucky, in 1896, but because of his father's profession he lived and went to school all over the United States. His first fifteen years were spent in Indianapolis, Richmond, Washington, Anaconda (Montana), Chicago, San Francisco, Alameda, Berkeley, Carmel, Portland (Oregon), and finally in Highland Park and Glencoe, Illinois. Four years were spent at the New Trier High School, and in 1921 Sample got a B.S. from Dartmouth after serving a hitch in the Navy in World War I. In high school and college he tried to excel in athletics, played the trombone in a college dance band, was an average student not fond of books and with no evident interest in any of the arts. He says, "I had no interest in or knowledge of any branch of the fine arts until I was well out of college." However, his passionate love for music began early (he plays the flute as Thomas Jefferson played the violin for better or for worse but with enthusiasm). He remem- bers that when he was eleven he used to hear the Russian Symphony Orchestra at Ravinia Park above Glencoe in a daily ritual: "I loved it and have derived an immense emotional pleasure from symphonic music ever since." As a child he drew caricatures, "nutty mugs," but this did not lead to his becoming a child prodigy.

Paul Sample is a quiet and retiring person, and finds enjoyment in being alone. He has always been imaginative and a dreamer although he has never felt the least urge to express his reveries. He was always sensitive and was, when younger, extremely jealous of his attachments to those he loved and admired. His intimates will recognize, I think, that these traits still exist, to which may be added a self-sufficient aloofness, and an imposing dignity. Perhaps the best single word to describe him is "reserved." He does not wear his- heart on his sleeve and is extremely difficult to get close to or to know well.

During four years, 1921 to 1925, spent recuperating from illness, he began painting. He studied in New York a few months in 1925, but in the same year he suddenly moved to California to be with an adored brother who was dying of tuberculosis. He continued his studies in the Otis Art Institute and then, almost savage in his loathing for commercial art, worked in his backyard in a makeshift studio under a tarpaulin. He was, he avers, first influenced by such an academic painter as Jonas Lie, who as early as 1922 was the first to. help him and criticize his work; but what carried Sample through primarily was the will to become a painter and a capacity for hard work. He believed in his star with an intense and flaming conviction.

He continually studied the human figure, composition, and color, drawing the figure at night with any group who could afford inexpensive models. But he says he got most digging by himself, continuously experimenting, and working from dawn to dusk. During these years he lived on very little: a disability compensation from the Veterans' Bureau, in 1926 from small wages as part-time instructor at the University of Southern California and from working in the Biltmore Art Gallery in Los Angeles. He found life as simple as this: he was happy when painting and unhappy when not painting.

He stayed on the West Coast ten years, learning his craft, spending several summers in Vermont, now his favorite state and residence, and making steady progress as a serious painter. In 1928 he married Sylvia Ann Howland of Montpelier, Vermont, who since has been his staunchest partisan and his most honest critic. The year 1936-1937 was spent in France and Italy (there is a series of watercolors which record certain aspects of this trip), and in the fall of 1938 he became Artist-in-Residence at Dartmouth where he has remained ever since.

At first, curiously like most beginners, he put no figures into his pictures since he could not draw them, but by 193 a figures were generally found in his arrangements as well as a tendency to simplify his forms to a greater degree and to work for more precision. He also became interested in more thoughtful and formal arrangements.

In the beginning he worked fast, resulting in a different kind of picture—one which might be described as having a sketchy technique. Now he plans a picture more thoroughly and paints more slowly. He has come to paint more and more in his studio from sketches done at the location, and is now composing at times without such sketches and building upon a mental concept rather than any event or thing he has actually seen. So his pictures become a product of his accumulated experiences rather than the record of isolated scenes. Models may be used to develop a compositional scheme rather than building the scheme about the models.

Once asked if he were not too aloof from his subjects, he answered: "I have real interest in what I paint but I think it is unnecessary for a painter to have more. What is important in any subject matter is its pictorial possibilities and not the painter's affectionate or sentimental attachment to it. I differentiate between subjects which, as objects of personal preference or affection, I may or may not wish to paint, and those which regardless of my personal interest in them offer exciting pictorial possibilities. I prefer thoroughbred hunters and yet I would rather paint an old and decrepit farm horse. I like fishing but rarely paint a fishing picture. I consider the subject only a source, a point of departure for the painter to expand from within himself in a pictorial direction dictated by the ever-growing importance of the painting itself and the progressive unimportance of the specific subject matter.

He is honest in analyzing the impulse which drives so many to painting:

1. The painter is doing what he most wants to do (selfish).

2 His desire to impart his feelings and enthusiasms to others; to depict his interpretation of life and how he feels about it to the world.

3. His desire to have his pictures looked at and admired.

Forthrightly he says, "I wish to be recognized as a great painter by my fellow men." As soon as he finishes a picture, he does,

in fact, lose interest in it. In earlier years his standards of success were not high but they gradually evolved along with his artistry. As he got to paint better his goal became ever higher.

"I consider painting," he says, "to be essentially a decorative expression and that unfortunately the more mature and profound the expression the smaller and more restricted necessarily will be its public. If a picture depends solely on its subject matter or literary aspect or naturalism it is not art at all."

This leads us to a point often insufficiently understood by the layman. Beauty should be inherent in a painting. Some reviewer of Winston Churchill's Painting asa Pastime (1948) points out Churchill's inadequacies as a painter by intimating that he can paint a beautiful scene and make, perhaps, a beautiful picture but a great painter can make an ordinary kitchen chair beautiful (as Van Gogh did), which Churchill, an audacious amateur, cannot do. This is what Sample means when he says that beauty inherent in a painting is more important than the depiction of a beautiful scene. The beauty should come from the mastery of the plastic elements, color, space, drawing, composition, rhythm and design.

The spectator should, in some measure, participate in the artist's satisfaction in presenting an idea in an orderly plastic arrangement or if he misses that, he should respond to the humor or tragedy or drama of the idea presented. Certainly it is true, as the writer has discovered, that the best way to appreciate painting is to try to master the technique oneself.

Paul Sample has, I think, the deepest sympathy, understanding, admiration, and kinship for and with Peter Breughel among all painters. He also admires the work of Giotto, Holbein, Lucas Cranach the elder, Greco, Vermeer, Cezanne, Pascin, Daumier, Degas, Bellows, Sloan, and Marin. In looking at another painter's work he is pleased most, he says, by his imagination, any evidence of fresh ideas, distinction of form or technique, in about that order. Color means a lot, naturally, but Sample includes that in form. Mood, sentiment, subject matter come last in his judgment. But in the last analysis he likes painting pictures much better than he does looking at them.

He has, I would say, no formal principles in painting and he has gone far beyond the elementary principles and theories he teaches his students. He depends more and more (so experience is seen to be most valuable) upon judgment, taste, and a feeling for order in building a picture. "Taste makes a painter," I have heard him say.

Paul Sample has never tried to lighten the mood or alter a picture in any way so that it would sell better. He paints as he feels and panders to no demand. He refused to do any more paintings for one of the big national cigarette companies, after he had done two or three, because of the limitations and restrictions placed upon him by the advertiser. This meant sacrificing a considerable sum of money, something an artist can use plenty of. Commissions that are handled wisely the painter enjoys, such as the Gimbel Pennsylvania Art Collection, of which more anon.

Paul Sample's watercolor technique is admirable, reminiscent to me, at least, of Winslow Homer. It demands quick and instantaneous judgment and selection of color, a perfect coordination of taste and skill in execution, all heightened by the fact that one false stroke will usually ruin the paper. He is a severe critic and I have seen him throw away as a failure what I thought was an excellent picture. He places more value, however, on his oils, as they are the result of longer reflection, more study and thought and a more careful use of materials. Marin he thinks is the greatest living watercolor painter.

When the Second World War descended upon us at Pearl Harbor, Paul Sample wanted to paint the war. Failing in his desire to enlist in the Navy, he became a war correspondent for Life magazine. His first assignment was to depict naval flying, which resulted in a visit early in the spring of 1942 to the Norfolk, Virginia, air base where he painted among other things a PBM at dawn, a PBY in the moonlight, and the control tower of the East Coast naval air station. Later in the spring of 1942 he cruised along the Atlantic coast on the carrier Ranger under then Captain (now Rear-Admiral) Calvin Durgin. Of the thirteen watercolors reproduced in Life the most exciting were action pictures of planes coming in and taking off. Memorable, too, is a watercolor of two Negro mess men admiring a torpedo plane.

In February 1943 he flew out to the Pacific on two different projects; first to paint life on a submarine on active duty in the Pacific, and secondly to depict life on some of our far-flung bases in that great southern ocean: Canton, Palmyra, Christmas Island, Midway, and along the Kona Coast in Hawaii. Those who have seen these pictures will remember particularly the painting of the submarine on its lonely course to Midway looking forward to the conning tower, "The Little White Church" on the Kona Coast remembered by many G.I.'s, his magnificent 'Air Strip at Midway," "Boxing Matches at Palmyra," "Native Fishing Boats," "Cargo Ship Unloaded," and others.

Paul Sample's last and most important war assignment was when he went out in September 1944 to the Southwest Pacific Theater to paint the Philippine operation. He flew to Pearl Harbor and then via Kwajalein in the Marshalls to Manus in the Admiralties where the operation was staged. For a time he was aboard the cruiser Portland and in an interval also took a 24-hour patrol on a PT boat contacting an American observer holed up in Dinegat. D-day found him in the Leyte Gulf and D-day plus 2 he was in Tacloban in the Philippines, which he used as a base in working with the United States Army.

From this emerged his masterpiece, and in my opinion by far the best painting of the war to come out of the United States (ironically enough Life never used it), his "Delirium Is Our Best Deceiver," which I'm proud to say I named. This depicts the wounded in a cathedral used as a field hospital at Palo, Leyte, P. I. The loneliness of wounded and sick men rotting from jungle fevers is most movingly and sympathetically portrayed. As a matter of fact Sample himself was there for a week with a twisted ankle and undoubtedly felt the loneliness and homesickness himself. The soldier's nostalgia for home, for mother, wife and sweetheart is imaginatively and daringly conceived. I believe this is to be in the Corcoran show in Washington this spring and I hope many of you will see it. Also from this trip came his famous "Red Beach," portraying one of the main invasion beaches on D-day plus 1. When he had gotten all the material he could use he returned home by air via Guadalcanal, Canton and Pearl Harbor to San Francisco. Most of his war paintings he finished in his Carpenter Art Building studio in Hanover. His notebooks from the Pacific he gave to the Baker Library in 1947.

Paul Sample's artistic record of the war ranks with the best war painting of World War I which was done, I think, by Paul Nash, C. R. W. Nevinson, Muirhead Bone, Norman Wilkinson, Eric H. Kennington, James Mcßey, Sir William Orpen, and G. Spencer Pryse. He, together with a few of the best American painters, has left us a priceless legacy of World War II, the gallantries and idiocies of which I trust may be marvelled at by future generations. I know of no painter of World War II who did a more superb job than Paul Sample.

Most of the year 1947 was spent with thirteen other painters in painting a series of pictures for the Gimbel Pennsylvania Art Collection. Sample chose to paint scenes in and around Philadelphia and the 64-page catalogue describing the collection had his "School Children in Independence Square" on the cover. This is a friendly and not too serious study of Independence Hall, the Barry statue, with a teacher in the foreground vainly trying to keep her pupils' attention.

Of the series Paul Sample painted, Dorothy Grafly writes that he "saw a busy, dirty, somewhat ragged waterfront" and found interest "in the hum-drum aspect of factory-lined rivers." She goes on, "Sample's Philadelphia is more the imper- sonal city of sophisticated, metropolitan vistas .... there are people in the squares; workers stream toward factories; but the city, not its people, claims first importance .... (he) sees the Delaware and the Schuylkill as dirty water thoroughfares dividing an endless repetition of grimy factories. . ... Sample (in his watercolors) prefers a diffuse wash."

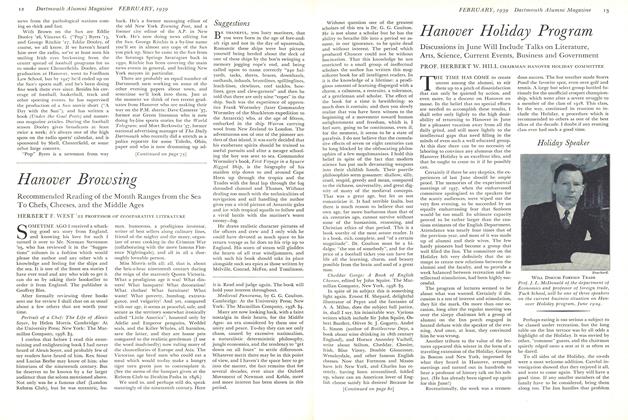

None of this, it seems to me, means very much, which is what Sample thinks of most art criticism. Sample painted what he saw and felt about Philadelphia and I have been told that his were the most popular pictures in the show. One on which he lavished his affection was the "Devon Horse Show, Night" which became one of the favorites of Mr. Arthur C. Kaufmann, executive head of Gimbel Brothers in Philadelphia. In this painting the life and movement of a horse show, the interest of hundreds of excited horse lovers is well portrayed in a pleasing arrangement of horses, grooms, and riders. Especially successful, 1 think, were "Skyline from the Philadelphia Museum of Art" (a watercolor), and "Rittenhouse Square" (oil).

Of them Paul Sample has written: "It has been my intention to present in each a pictorial statement which is wholly characteristic of the place," and "the assignment I found most rewarding in subject matter material—as evidenced by the fact that I found in a comparatively short period many more strongly appealing subjects than I found it possible to undertake."

For the first time since 1937, Paul Sample in April had a one-man show of watercolors and oils in New York at the Associated American Galleries.

After more than ten years at Dartmouth Paul Sample is forced to the conclusion that a college is not a good breeding ground for the creative arts as a student's time is too crowded with other things. Nevertheless, he has had a really profound influence on many students and adults of the community in the development of painting as a pastime, and in one or more instances in the development of

professional painters. "Painting," Winston Churchill has written, "is a companion with whom one may hope to walk a great part of life's journey, and happy are the painters, for they shall not be lonely. Light and colours, peace and hope, will keep them company to the end, or almost to the end, of the day." I agree, and if I may speak for myself as one of Paul Sample's students, I can say that his influence has been great. For two or three years soon after he came in 1938 I watched him paint and unconsciously absorbed a lot. I began painting around 1940 but only half-heartedly as time was limited and other duties made it impossible to devote as much time as a painter must to his craft. Fatigue is not good for a painter. No "Sunday painter" can become really good in the professional sense as painting demands a one's waking hours. Not until the winter 0 1947-1948 did I have a real chance to paint when I was forced to "take things easy for the period of a year or so. The results were negligible in an objective sense but not to me personally. I was never happier than when painting and the therapeutic value was enormous. During a whole year of enforced idleness I can honestly say I was never bored or lonely, for always there was a new problem facing me on the easel; there was the joy of progress made, and there was an increasing pleasure in the use of color. With Churchill I came to believe in audacity: "Just to paint is great fun. The colours are lovely to look at and delicious to squeeze out. Matching them, however crudely, with what you see is fascinating and absolutely absorbing. Try it—if you have not done so—before you die."

William Zorach, the sculptor, has something intelligent to say about teaching art: "The idea of art is abstract. An instructor cannot teach art. He can only point a way towards understanding, give a clue to its meaning and help with tools and technical information." This Paul Sample has accomplished in great measure. He has stimulated, encouraged and helped many. I can name but a few of the hundreds who have studied with him. Peter Gish '49 he considers one of the most promising young painters he has ever helped. He recalls Stephen V. Bradley '39, Charles H. Weisker '41, Richard L. Brooks '39, Charles McLane '41, Charles H. Geer '44, Douglas B. Leigh '46, all of whom show professional promise; others who have studied with Paul Sample with great profit are Ann Stevens, Susan Chambers, Betsy Chalfant, Dorothy Forster, L. K. Neidlinger '23, Mr. Joseph Henry, Allan H. Macdonald, Larry Bankart '10, Norman Arnold, Jane F. Lawson, George C. Wood, and many others. He has frequent letters from alumni, many of whom never worked with him, asking for advice. The habit of carrying and using a sketchbook spread through V-12 and many in the armed services during the war and still continues. This impetus came from Paul Sample.

Education is a curious and intangible thing. Of a series of lectures in a course only the one which caused a brief spell of incandescence in the listener will be reraembered. Whole courses devoted to memorizing a textbook are forgotten before the ink is dry on the final examination. Unless one's intellectual curiosity is aroused, and the desire to know awakened, the process of education will cease on graduation, and with graduation a man is just beginning to know a little something. One session in a drawing class with Paul Sample (in which no academic credit is given), in which a sense of beauty and form is awakened and the rewards of serious creative work glimpsed, might be as valuable an experience as the student will get in his entire four years. Painting leads to an insight into the beauties of the world, to a greater knowledge of life and people, and to an increase in one's faculty of observation. Before he knows it the student may find himself, in Henry Thoreau's sense of the word, alive. If Paul Sample so stirs one or two a year he has performed a miracle, and miracles are something to respect in this sense.

Let me end with a paraphrase of a statement written by my late and esteemed friend Cunninghame Graham about Joseph Conrad:

"There is a fountain in Marrakesh with a palm tree near it, a gem of Moorish art, with tiles as irridescent as the scales upon a lizard's back. Written in Cufic characters, there is this legend, 'Drink and admire.' "

When you see Sample's paintings, "Look and admire; then return thanks to Allah who gives water to the thirsty and at long intervals sends us refreshment for the coul."

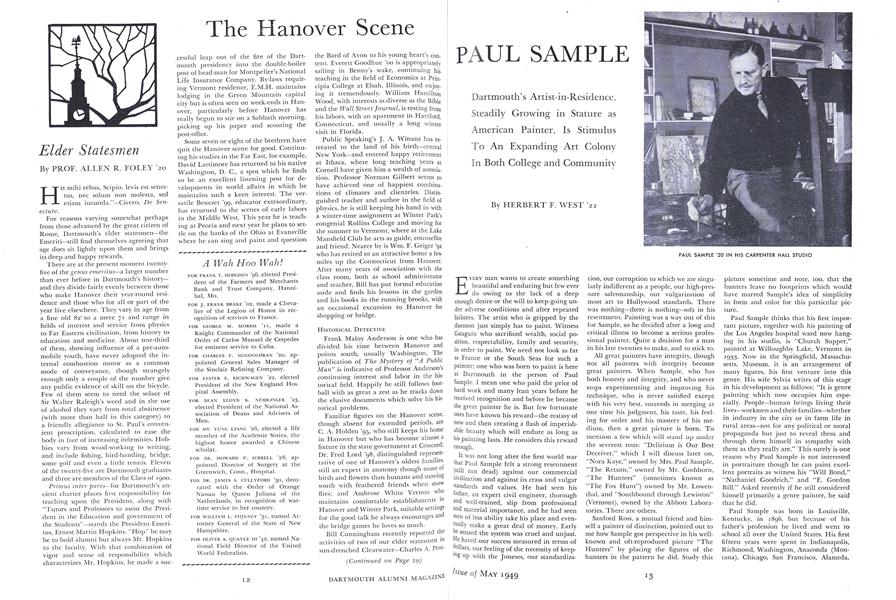

PAUL SAMPLE '20 IN HIS CARPENTER HALL STUDIO

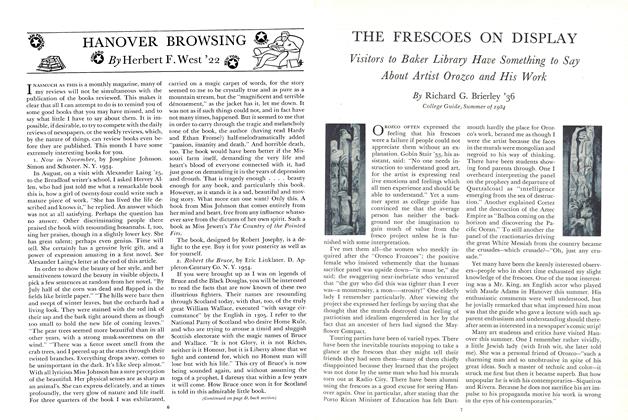

REPRESENTATIVE OF SAMPLE'S GENRE PAINTING, and also of his special interest in the New Hampshire and Vermont countryside, is this oil depiction of maple sugaring, painted for the "Country Gentleman's" modern American collection. This reproduction does not indicate the brightness of the original.

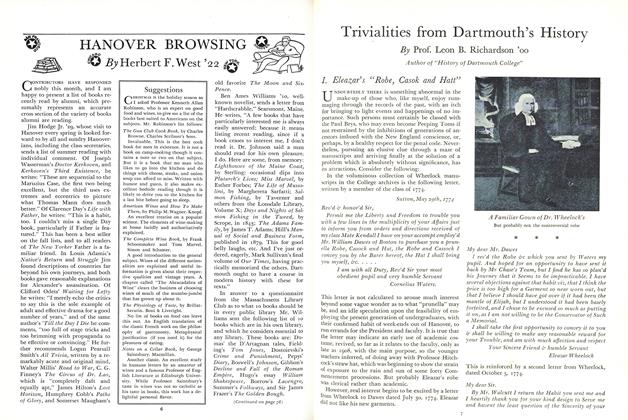

THE AUTHOR AWAITS THE VERDICT: Prof. Herbert F. West '22, who has become one of Paul Sample's star faculty pupils, asks Dartmouth's artist-in-residence to criticize his watercolor of a woodcock. Through his informal classes, both outdoors and in Carpenter Hall, and through his willingness to help others. Sample has given many a grateful amateur his start in the hobby of painting and sketching.

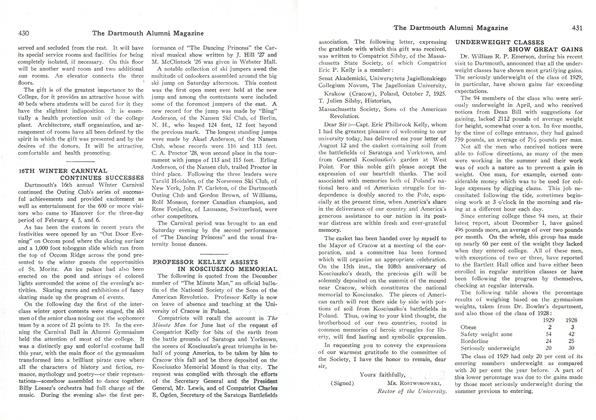

THE MOST POPULAR PAINTING, by vote, in the Philadelphia showing of the Gimbel Pennsylvania Art Collection was the above oil, "Rittenhouse Square," which Sample did as part of his series on Philadelphia. It is another fine example of Sample's artistry in the arrangement of figures.

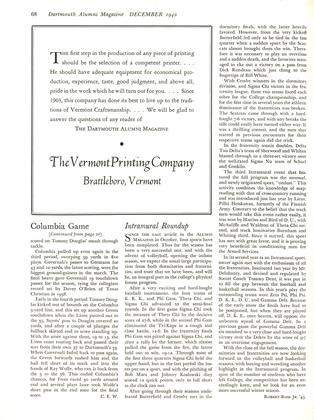

LABOR DAY WEEK-END is the title of this oil painted for the Abbott Laboratories of North Chicago, for whom Sample has done some of his best pictures. It is reminiscent of the artist's famous "Janitor's Holiday" which hangs in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and again illustrates Sample's masterful ability to catch the beauty and the spirit of the rolling New England countryside.

£.AUL SAMPLE'S WATERCOLORS are free and informal in style, and some critics rate them even above s oils. Typical is this watercolor done on a fishing trip to the Miramichi, New Brunswick, last summer.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

May 1949 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, EDWIN C. CHINLUND, GEORGE B. REDDING -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

May 1949 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONAIJS L. BARR, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Article

ArticleThe Experimental Theatre

May 1949 By BENFIELD PRESSEY, -

Class Notes

Class Notes1931

May 1949 By A. W. LAUGHTON, WILLIAM H. SCHULDENFREI, EDWIN F. STUDWELL -

Class Notes

Class Notes1934

May 1949 By FRANKLYN J. JACKSON, WILLIAM H. SCHERMAN -

Article

ArticleElder Statesmen

May 1949 By PROF. ALLEN R. FOLEY '20

HERBERT F. WEST '22

-

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

November 1934 By Herbert F. West '22 -

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

December 1935 By Herbert F. West '22 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

February 1939 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

March 1943 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

May 1949 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Books

BooksSIDEWHEELER SAGA

July 1953 By HERBERT F. WEST '22

Article

-

Article

ArticleBEQUEST TO COLLEGE

June 1917 -

Article

Article"Nothing Less..."

June 1950 -

Article

ArticleJohn Cotton Dana Library

MARCH 1966 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

February 1951 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

ArticlePROFESSOR KELLEY ASSISTS IN KOSCIUSZKO MEMORIAL

March, 1926 By Mr. Rostworowski -

Article

ArticleIntramural Roundup

December 1942 By Robert Ross Jr. '45