By Budd Schulberg'36. Random House, 1950, pp. 388, $3.50.

Budd Schulberg's new book is an imaginatively conceived and beautifully written story of a man, a marriage and a decade. Manley Halliday was born with a big talent and exhibited it in his first novel at the age of 23. His World War I novel anticipated and perhaps helped to create the cynicism his generation felt about war. He was a kind of emotional seismograph, feeling and recording the entire social upheaval of the twenties, but he recorded his age in fiction, not in graphs, with the artist's touch, not merely the camera eye. He married a beautiful girl in postwar Paris and together they became a symbol of their age.

The Disenchanted picks up Manley Halliday in Hollywood in the late thirties after he has spent himself and his fortune, after his wife has cracked and her weakness has precipitated his own breakdown. The action of the novel concerns a trip Halliday takes to Webster College to get background for a picture he is hired to write about Webster's famous Mardi Gras. His collaborator is Shep Steams, a Webster graduate of the thirties, who is also a child of his times

Webster is obviously Dartmouth and Mardi Gras is Carnival, but little is to be gained by identifying persons who may seem familiar to those of us who know Hanover. There is no malice in the book about anyone. It is equally clear that Manley Halliday's prototype is F. Scott Fitzgerald and to those who know Fitzgerald's work the book will have extra significance as a work of literary criticism.

The story of Halliday's life is told in a series of flashbacks as Halliday discusses his work with Stearns. The transition is so smooth that it is never noticed and the style so artful that the reader becomes perfectly attuned to the mood of diabetic and drunken nostalgia which overcomes Halliday on the trip.

The Disenchanted is a professional job in the finest sense of the word. It is certainly Schulberg's best work. The style is brilliant and some of the passages describing Halliday's physical condition and dreaming memories could hardly be duplicated by any American writer working today. To those of us who have followed Budd Schulberg's career this book will be a particular joy. It represents a culmination of his hard work and constant application of his own thoughts and beliefs. Many of these can be traced to what he learned in the Sociology and English Departments at Dartmouth. It may be a comfort for aspiring undergraduate writers to know that a formal education is not necessarily a handicap. Unlike Manley Halliday, who learned too late, Budd Schulberg acknowledges the need for acquiring some of the world's wisdom in order to continue his growth as an artist.

Perhaps Budd's portrait of Halliday is more merciful than he deserved. Not all alumni will share the compassion for Halliday's broken career that the novel expresses, but doesn't Sinclair Lewis unconsciously admire Babbitt and Dodsworth and Kennicutt at the same time that he mocks them? To those of us who live more prosaic lives, Halliday's career may seem a bizarre tragedy, but The Disenchanted reveals through Halliday some of the universal problems of America between wars. If Budd can apply his same brilliant style and sound analysis to other aspects of our civilization beyond the fields of entertainment sport and literature, X think he is destined to be one of the great writers of our generation.

The book is the November choice of the Book of the Month Club.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

December 1950 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1935

December 1950 By HENRY R. BANKART JR., JOHN WALLACE, ROBERT w. NARAMORE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1942

December 1950 By JAMES L. FARLEY, JOHN H. HARRIMAN, ADDISON L. WINSHIP II -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

December 1950 By TRUMAN T. METZEL, COLIN C. STEWART 3RD, LEON H. YOUNG JR -

Class Notes

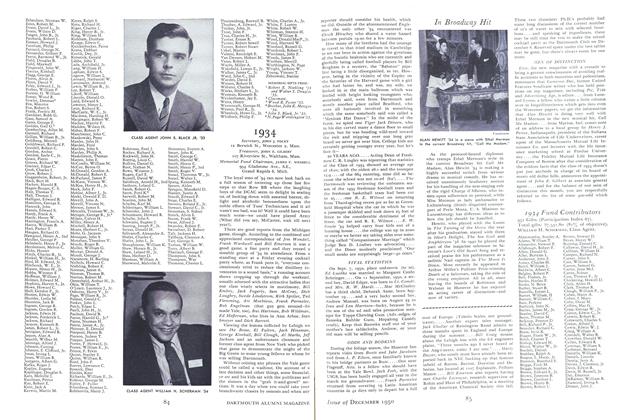

Class Notes1934

December 1950 By JOHN J. FOLEY, JOHN E. GILBERT, WILLIAM H. SCHERMAN -

Article

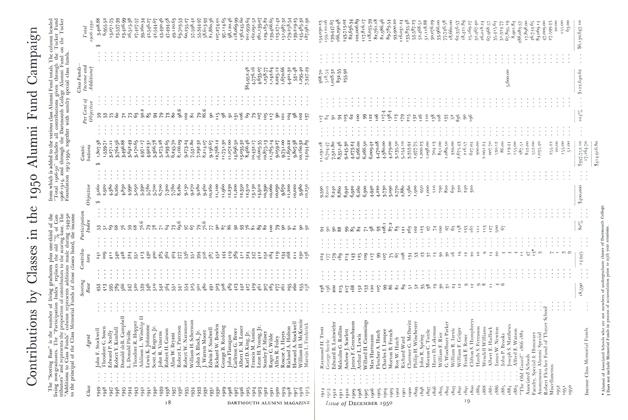

ArticleContributions by Classes in the 1950 Alumni Fund Campaign

December 1950

JOSEPH A. MILLIMET '36

Books

-

Books

BooksFITZ HUGH LANE.

MARCH 1973 By ALEXANDER LAING '25 -

Books

BooksPORTRAIT OF PATTON.

December 1955 By COL. JACK C. HODGSON, USAF (RET.) -

Books

BooksCOLOMBIA: LA PRESENCIA PERMANENTE.

December 1961 By ELIAS L. RIVERS -

Books

BooksBig Apple Circus

JUNE 1983 By Frank Small Wood '51 -

Books

BooksMelodies Lingering On

September 1980 By H. Wiley Hitchcock '44 -

Books

BooksFACULTY PUBLICATIONS

April 1924 By Malcolm M. Willey