The mail resulting from Professor Knight'sarticle in the December issue has been un-usually heavy and has included requests forhundreds of reprints. Because of their desireto print all of the excellent letter following,the editors have space this month for onlythree of these communications.

Let Down

To THE EDITOR: I am writing to you with respect to Professor Knight's article in the December issue of the MAGAZINE. I am sure you will receive comments from many readers. This is a healthy sign when controversial matters are discussed in print. I trust you will see fit to give due space in a succeeding issue to a reply to the Knight article.

I, for one, have several "bones" to pick with Professor Knight on his handling of his subject.

First of all, when someone writes an article of this nature, such as Professor Knight's, he usually approaches it in one of two ways. He either uses the so-called logical technique, strongly buttressed with facts, leading to a definite conclusion. His reasoning, whether deductive or inductive, can be clearly traced, and gives the reader a comprehensive view of the subject under discussion. Unfortunately, this kind of treatment is difficult to make interesting, and often results in an academic and pedantic treatise (that is probably a chief reason why so many textbooks are boring). The second approach is less difficult. It is more subjective, less intellectual, frequently less well organized, and more contemporary in idiom. It uses anecdotes freely and "names the names" candidly. This approach is currently in great favor with many species of politician, including Congressmen, bureaucrats, lobbyists, "special interest" organizations, and newspaper columnists. It often makes interesting reading. Just as often, it is emotionally confusing and intellectually misleading.

Professor Knight has chosen the latter approach. He speaks often in the vernacular, and uses "little stories" and allegories to illustrate his points. Or perhaps he is looking for points to illustrate his stories. In any event, what starts out to be a punchy and vigorous statement winds up as a very hazy and nebulous collection of "cures," quotations, and after-dinner "chucklers."

Now to get down to cases. Professor Knight is unmistakably writing with scorn for his targets, but it is hard to tell whether this attitude is inspired by fear or utter disdain. He pictures these "pseudo-liberals" as ethereal idealists—poor misguided souls. He is sorry for them, as one would be for errant children, unwittingly led astray. Now Professor Knight may be right, but his complete confidence in the correctness of his own position rather puts the burden of proof upon him. He must prove the stupidity and folly of his chosen opponents or he has no right to ask us, his readers, to take him seriously. He must show us that these so-called dreamers are bad medicine and, having established that, indicate what practical measures we can take to oppose them. This is not asking too much, since Professor Knight intimates that he knows the "facts of life," and he is presumably willing to share them with us. Else he wouldn't have taken the trouble to write the article at all.

Having disposed of his adversaries rather condescendingly in the first three paragraphs (mixing in a little poetical evaluation along the way), he then proceeds to his own definition of liberalism, and this is where the whole thing begins to cloud up for Professor Knight and, incidentally, for me. His liberalism, as he readily admits, is a philosophical product (by no means God-given) of such men as Locke, Mill, and Adam Smith, whose theories simply reflected and guided the trend of the times. My quarrel is not primarily with Professor Knight's "propositions," although they are much too sketchy to be more than platitudinous generalizations, which are so reminiscent of Democratic and Republican party platforms. What I do object to specifically is Professor Knight's perspective, which I think is smaller than it should be. He seems to have forgotten that the very Englishmen whom he admires (I think) were actually the "radicals" of their day and that their particular "ism" just happened to be liberalism. They were daring to assert the property rights of the mass of the people against the "divine right" of kings. Men like Hobbes, who were proponents (and pretty good ones, too) of aristocracy and hereditary rule, had much the same dislike for these new "liberals" as Professor Knight has for the "planners." It all depends upon what century you happen to be living in.

DOUBTS LIBERALISM IS CONSERVATIVE

Yet the tide of the Protestant Reformation, the opening up of world trade, and the birth pangs of industrialism could not be denied by the "old guard." It is significant that the middle-class, or bourgeoisie, were the backbone of this movement. Constitutional government, as we know it, developed from the efforts of these "radicals." Professor Knight says that liberalism is "conservative in its selection of means," but if he believes that, he just does not remember his history. The French and American revolutions were anything but conservative in their execution. They were bloody, spirited, and risky, and they certainly dealt with the facts of lifeand death. The rise of the middle class has been the dominant social, economic, and political movement to the past two hundred years. And a good bit of that rise was not achieved around a conference table. I am not saying this to advocate violence, but merely reminding Professor Knight of some things he already knew, but just forgot to mention. I am also saying that if Professor Knight had been a contemporary of John Adams, Washington, and George the Third he certainly would have been classified as a "damned radical," and would probably have been severely dealt with by the Crown.

With the passage of time, and the flowering of the Industrial Revolution and the exploration of the geographical frontiers of the world, the liberals (as Professor Knight has defined them) became the dominant group in many national governments, and certainly in the United States. The old royalists, and their offshoots, the Federalists, were swept aside by the Republicans. While America was a-building, there was room for all. Immigrants were welcomed. Land was to be had for the asking —or the taking. But soon this gigantic expansion began to slow down. Physical boundaries were reached, the new frontiers were now in the laboratories and the factories, the economy became more complex, and the people, now incredibly varied in race, creed, color and education, were beginning to rub against each other, sometimes with unpleasant social consequences. The time had passed when, if you didn't like the town you were in, you could get some friends together and start a new one. There was less movement in every sphere of activity. However, the relatively new middle class had done well for itself. Success was now popularly based on monetary accumulation and political influence rather than "breeding" and family lineage. The liberals, both practical and philosophical, had won a well-deserved victory. Having gained political ascendancy and economic prosperity, they were now on the alert for any attempts, whatever the source, to infringe upon their hard-won gains. Instead of being, in the United States, "his Majesty's loyal Opposition," they had gotten rid of "his Majesty" and jumped into the driver's seat themselves. There is nothing odd in this kind of transformation. To liberals, it represents progress. It is quite in accord with human nature. When a man is trying to get something, he is aggressive and ambitious—he may even throw his weight around. But after he achieves that "something" his attitude changes. He becomes more interested in preserving what he has against other aggressive and ambitious men who want that "something" (be it farm, factory, political office, or what have you) for themselves. That transformation applies to the British-inspired liberalism, which really became powerfully entrenched in America after the Civil War. The old liberalism has now become conservative in its thinking and functioning (it wasn't born that way, as Professor Knight seems to believe) simply because it now holds the reins. In itself, the attitude of the liberals is neither "good" nor "bad." It is simply the way most human beings would act in the circumstances.

OFFENSE, NOT DEFENSE, NEEDED

So now Professor Knight and the liberate are busy fending off attacks. These are the attacks which are bound to come, because society (including its economic theories) is not static. As long as there are people, there will be new ideas, as well as revisions of old ones. We may criticize the attackers, as Professor Knight has done, by ridiculing them, by calling them names (either actually, or by innuendo), by claiming that they are charlatans and deceivers. If we do that, we are doomed to defeat in the long run. For in politics and economics, just as in football and in war, it takes a good, sound offensive, not a defense, to win. Professor Knight is so busy showing up the fallacies and deceptions of the other team, that he has left himself wide open. He admits weaknesses in his own liberalism and he may be guilty of a contradiction or two himself. His opposition to the Roosevelt and Truman regimes is so belaboringly obvious that we might as well drop the disguise, and call it just that. I'm not championing Roosevelt or Truman. I just want to call a spade a spade. The New Deal and the Fair Deal represent much of what is hateful to Professor Knight's liberalism. Yet, curiously enough, some of the governmental practices he criticizes are products of the Republican party, which has fallen heir in American society to the liberalism of the eighteenth century. I refer to high tariffs, opposition to present uses of antitrust laws, and margarine taxes (supported by many midwestern Republican legislators). These causes have been consistently championed by conservative groups in American politics. However, in the past 25 years there has been considerable crossing of traditional party lines on many issues, and it is dangerous to be too inclusive when ascribing a particular point of view to an entire party.

Perhaps I do Professor Knight an injustice to assume he is a Republican, politically speaking, and if so, I stand corrected. However, if I am mistaken, and he is actually an "independent liberal," then what sort of program should be ascribed to him? As I said at the beginning of this letter, I think we have a right to know what Professor Knight proposes to do about this greatest issue, as he sees it. After the unmasking party then what?

Despite my own expectations, I am sorry to report that we have been "let down." Professor Knight's invective appears to have dissipated his energy. He expires rather meekly. His statements about the money supply and the evils of "competitive banking" leave me stone cold, and considerably bewildered. With my uneconomic eye, I confess I don't see what he is driving at, nor just what relation this has to what he has so painstakingly been debunking. His second "curable factor" is "sticky prices." I am ashamed to admit that the immediate image (probably Freudian) which I got from this phrase was that of a small child who had just gotten his fingers into a molasses bowl. Professor Knight then takes us back to "monopoly"—and leaves us there, high and dry. Then, he says, when depressions come, the government blames it all on private enterprise, and takes over. But he hasn't told us whose fault the depression really is, or how to avoid it. Perhaps we can't. Presumably the whole thing is tangled up with "sticky prices" which are certainly somebody's fault (perhaps a lot of peoples', including Professor Knight and myself!). At any rate I wish Professor Knight had spent a little more space on this end of his article, rather than on the front end.

Finally, we are told that in the export market "private dumping" is less obnoxious than "government dumping" because foreigners can better maintain their pride. I always thought the evils of "dumping" were more important than who happens to be doing it, but then I may be wrong.

In conclusion, may I say that I am disappointed that Professor Knight has not given us more for our money. We are ripe for intelligent leadership. I, and many others, are frankly puzzled, and not a little worried by many things going on in the world today. We would certainly appreciate a little light on the "issues," whatever they may be. I am ready to be convinced that Professor Knight's liberalism is worth defending (and extending), provided the facts are available and the reasoning sound. But all I can hear is the stern order to the paternalists to "stop hiding behind language."

"Professor Knight, come out from behind that chair!"

West Lebanon, N. H.

EDITOR'S NOTE: Professor Knight is a registered Democrat.

Required. Reading

To THE EDITOR: Professor Knight's article on "Pseudo-Liberalism" published in your December 1949 issue was the finest of its kind that I have ever read.

It should be required reading in everyschool, college and home. . . .

Westfield, N. J.

Loose Semantics

To THE EDITOR: I want to comment on Professor Knight'spiece in the December MAGAZINE.

It seemed to me generalized claptrap andpoor on every count. I have read it throughseveral times and find no constructive ideashidden in the thickets of Professor Knight'sprejudices. It is easy to understand an anguished yearning for the good old days; butthis after all is an old theme and one whichscarcely merits the space you have given it.

Perhaps the most surprising aspect of the article is its non-reliance on authorities or on specific example. No names or instances are permitted to penetrate the helter skelter of Professor Knight's assertions.

Paternalists and pseudo-liberals are not identified, but considered only as a sorry group of people who can most likely be found in Washington. They are given no names; but the clear assumption is that they are, generally speaking, all or most of the people who subscribe to any or all of the New Deal-Fair Deal approaches to the questions of American society.

This failure to identify people and issues must be deliberate. It certainly is an understandable evasion, because identification would immediately invalidate most of Professor Knight's conclusions. Either that, or the Professor would have to grant that he does not approve of the democratic process.

"Government has .been the foremost abettor of internal monopoly. It has used import duties, quarantine regulations, currency manipulation, and the like, to keep firms out of the market. It has shut out substitute products by such means as the outrageous tax on colored margarine Its farm program, for example, has followed the absurd procedure of first making productive power idle and then looking around afterwards to see if something else might be done with it."

This is typical of Professor Knight's loose semantics and brittle approach to his subject. It is, in fact, first cousin to demagoguery. The "Government" that Professor Knight is sniffling at is of course one chosen by the votes of the people. He seems to be suggesting a Government in which only those who agree with him would have a voice. Fortunately, that does not seem likely ever to be the case.

One last word. The editorial note on Page 3 of the MAGAZINE makes use of quotation marks in introducing Professor Knight's story in a way which seems questionable to me. As I read it, I had the very definite impression that the MAGAZINE'S editors (and therefore the College) agreed with this lishwifely essay. I would be most disappointed to believe that this is so.

New York, N. Y.

EDITOR'S NOTE: Professor Knight's article represented his own personal point of view and was clearly presented as such. Because of the frequency with which one speaks of great issues at Dartmouth, it is common practice to quote "the greatest issue" when singling out any one of them as most important.

Frank M. McCutcheon '76

To THE EDITOR: The passing of Frank Moses McCutcheon in his 95th year, who was Dartmouth's oldest living alumnus at the time of his death on December 2, 1949, may have been the end of a career, but not the end of that sturdy spirit of Scotch-Irish extraction, polished and fixed by the culture of Latin and Greek scholarship. Such things do not end.

Measured by material standards Mr. McCutcheon was not a wealthy man, but he lived an opulent life filled with understanding, kindness and a high regard lor his friends and neighbors, who in turn reflected this feeling to him and others.

In his reminiscences, he showed this writer his father's license to teach in the public schools of New Hampshire, which license was dated at Bow, November 1812. And he told of how when he attended college in the Class of 1876, his tuition fee was about $63 per year, and board and lodging at Hanover for students was $2.50 per week; yet it was a struggle for his family to afford these amounts.

In this day and age,.... it was refreshing to have known Mr. McCutcheon, and Dartmouth may well be satisfied with the mold in which she casts her sons.

Kingston, N. Y.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

February 1950 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Article

ArticleBack to Hanover in December

February 1950 By WILLIAM H. HAM '97 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1905

February 1950 By ROYAL PARKINSON, GILBERT H. FALL, FLETCHER A. HATCH -

Class Notes

Class Notes1943

February 1950 By ELMER G. STEVENS JR., STANTON B. PRIDDY, THEODORE R. HOPPER -

Article

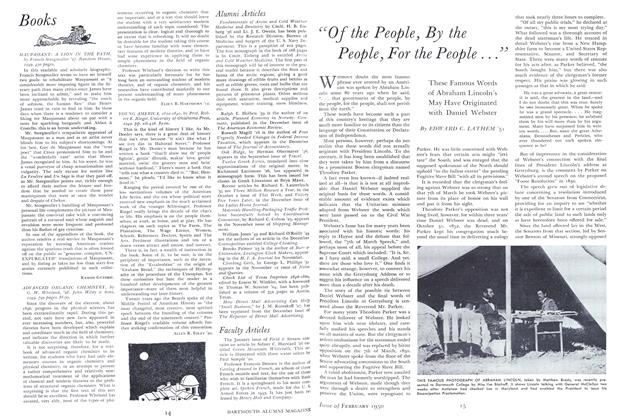

Article"Of the People, By the People, For the People..."

February 1950 By EDWARD C. LATHEM '51 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1936

February 1950 By NORBERT HOFMAN JR., JOHN E. MORRISON JR., ROBERT L. PATERSON