These Famous Words of Abraham Lincoln's May Have Originated with Daniel Webster

WITHOUT doubt the most famous phrase ever uttered by an American was spoken by Abraham Lincoln some 86 years ago when he said, ". . . that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth."

These words have become such a part of this country's heritage that they are much more familiar to its citizens than the language of their Constitution or Declaration of Independence.

Most persons, however, perhaps do not realize that these words did not actually originate with President Lincoln. To the contrary, it has long been established that they were taken by him from a discourse by a prominent Boston clergyman named Theodore Parker.

A fact even less known—if indeed realized at all—is that it is not at all improbable that Daniel Webster supplied the original basis for these words. A considerable amount of evidence exists which indicates that the Unitarian minister adapted from Webster the words which were later passed on to the Civil War President.

Webster's fame has for many years been associated with his historic words: his reply to Hayne and the debate that followed, the "7th of March Speech," and, perhaps most of all, his appeal before the Supreme Court which included: "It is, Sir, as I have said, a small College. And yet, there are those who love it." One finds it somewhat strange, however, to connect his name with the Gettysburg Address or to suggest his influence on a speech delivered more than a decade after his death.

The story of the possible tie between Daniel Webster and the final words of President Lincoln at Gettysburg is centered about the Reverend Mr. Parker.

For many years Theodore Parker was a devoted follower of Webster. He looked upon him with near idolatry, and carefully studied his speeches and his stands on all matters of state. But the clergyman's ardent enthusiasm for the statesman ended quite abruptly, and was replaced by bitter opposition on the 7th of March, 1850, when Webster spoke from the floor of the Senate advocating concessions to the South and supporting the Fugitive Slave Bill.

A rabid abolitionist, Parker now assailed the man he had formerly worshipped. The arguments of Webster, made though they were through a desire to strengthen and preserve the Union, were repugnant to Parker. He was little concerned with Webster's fears that certain acts might "irritate" the South, and was enraged that the supposed spokesman of the North should uphold "to the fullest extent" the pending Fugitive Slave Bill "with all its provisions."

It is recorded that the clergyman's feeling against Webster was so strong that on that 7th of March he took Webster's picture from its place of honor on his wall and put it from his sight.

Theodore Parker's opposition was not long lived, however, for within three years' time Daniel Webster was dead, and on October 31, 1852, the Reverend Mr. Parker kept his congregation much beyond the usual time in delivering a eulogy that took nearly three hours to complete.

"Of all my public trials," he declared at the outset, "this is my most trying day." What followed was a thorough account of the dead statesman's life. He treated in detail Webster's rise from a New Hampshire farm to become a United States Representative, Senator, and Secretary of State. There were many words of censure for his acts after, as Parker believed, "the South bought him," but there was also much evidence of the clergyman's former respect. His praise was glowing in such passages as that in which he said: He was a great advocate, a great orator; it is said, the greatest in the land,—and I do not doubt that this was true. Surely he was immensely great. When he spoke he was a grand spectacle. . . . He magnetized men by his presence; he subdued them by his will more than by his argument. Many have surpassed him in written words But, since the great Athenians, Demosthenes and Pericles, who ever thundered out such spoken eloquence as he?

But of importance in the consideration of Webster's connection with the final lines of President Lincoln's address at Gettysburg, is the comment by Parker on Webster's second speech on the proposed "Foote Resolution" in 1830.

The speech grew out of legislative debate concerning a resolution introduced by one of the Senators from Connecticut, providing for an inquiry to see "whether it is expedient to limit for a certain period the sale of public land to such lands only as have heretofore been offered for sale."

Since the land affected lay in the West, the Senators from that section, led by Senator Benton of Missouri, strongly opposed the bill; and held it to be an unfriendly attack on their interests by the Northern states, particularly those of New England.

On January 19, 1830, Senator Robert Y. Hayne of South Carolina joined forces with the Westerners and entered upon an assault against New England so offensive as to require an immediate answer. The following day Daniel Webster took the floor and masterfully defended his native region.

Although hardly justified by the content or tone of Webster's remarks, Hayne took them to be a personal affront, and determined to continue debate the next day. Despite being informed that Senator Webster's presence was required in the Supreme Court where he was pleading a case, Hayne refused to delay and persisted that he be afforded immediate opportunity of "returning the shot."

It was a challenge that could hardly be denied, and Webster replied, "Let the discussion proceed; I am ready now to receive the gentleman's fire."

Hayne spoke for about an hour that day; and upon the Senate's reconvening on Monday, he spoke for an additional two hours and a half, continuing the bitter attack on New England. His treatment also of that region's defender was in general far from courteous, and he concluded by asserting the right of states to invalidate acts of Congress—a doctrine which three decades later was to take his state out of the Union and begin the Civil War.

When Senator Hayne had finished, Webster rose at once to make answer, but yielded to a motion for adjournment due to the lateness of the hour. On January 26, with every inch of standing space in the chamber and the halls and on the stairways filled, "Black Daniel," the Senator from Massachusetts, made reply to Hayne in what is probably his most monumental piece of oratory.

He began by defending himself against the attack leveled upon him. Next, he once again took up a firm defense of New England. And finally, he proceeded with his main task which was to refute the constitutional stand of the Senator from South Carolina. Of the right of any state to nullify Congressional acts, he declared "that the people may, if they choose, throw off any government when it becomes oppressive and intolerable, and erect a better in its stead."

This, however, he held to be a different matter from the right of a state to "annul a law of Congress." He denied "that it is constitutional for a state to interrupt the administration of the Constitution itself. And in arguing that the Constitution of the United States is an instrument of the people and not of the states, Daniel Webster spoke the lines which may well be the precursors of those made famous at Gettysburg 33 years thence. He said: It is, Sir, the people's Constitution, the people's government, made for the people, made by the people, and answerable to the people.

These words were spoken during a period when Theodore Parker was still sympathetic to Webster's causes and was following his career most attentively. That he knew the speech well and esteemed it highly is attested by his words in the eulogy. Referring to it as "the greatest political speech of Daniel Webster," Parker declared, "his speech is full of splendid eloquence; he reached high, and put the capstone upon his fame. . . ."

That this particular passage on the "people's government" may have struck, the clergyman's fancy, and that he consciously adapted it to use in his own speeches, can only be suggested; but Parker is known to have used similar phrases at least three different times in public addresses.

There appears to be a development of the Webster phrase in the resemblance of a passage from a speech delivered by Parker in Boston in 1850, while Webster still lived. On this occasion he said: There is what I call the American idea. . . . This idea demands, as the proximate organization thereof, a democracy, that is, a government of all the people, by all the people, for all the people. . . .

Parker also used a like phrase in an address four years later, and again in a discourse delivered at the Boston Music Hall on Independence Day, 1858, entitled "The Effect of Slavery on the American People."

This latter discourse was soon brought forth in printed form, and William H. Herndon, Lincoln's law partner, in his biography Abraham Lincoln, records as follows his returning from Boston at about that time: I brought with me additional sermons and lectures by Theodore Parker, who was warm in commendation of Lincoln. One of these was a lecture on "The Effect of Slavery on the American People," which was delivered in the Music Hall in Boston, and which I gave to Lincoln, who read it and returned it.

Herndon then notes that upon receiving the pamphlet back from the President, he found underscored in pencil the lines: Democracy is direct self-government, over all the people, for all the people, by all the people.

And on November 19, 1863, Abraham Lincoln used these words in substance to close his address at the national cemetery at Gettysburg, thus giving us the bestknown phrase ever uttered by an American, and completing the development of a group of words which may well have begun with Daniel Webster.

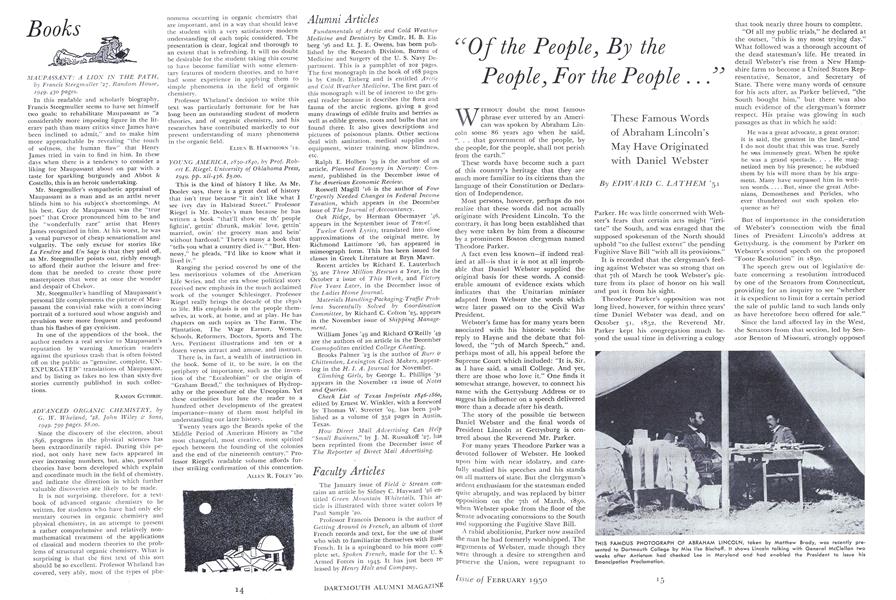

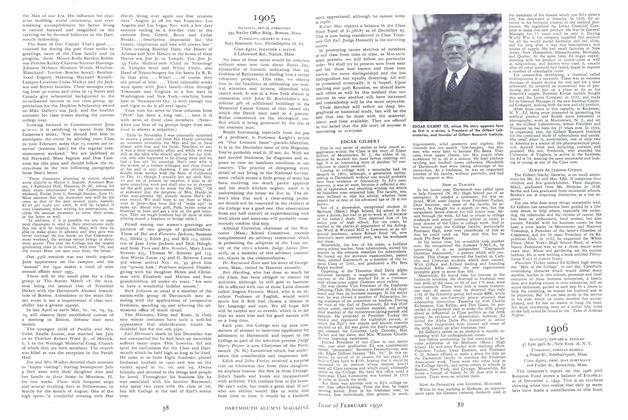

THIS FAMOUS PHOTOGRAPH OF ABRAHAM LINCOLN, taken by Matthew Brady, was recently presented to Dartmouth College by Miss Use Bischoff. It shows Lincoln talking with General McClellan two weeks after Antietam had checked Lee in Maryland and had enabled the President to issue his Emancipation Proclamation.

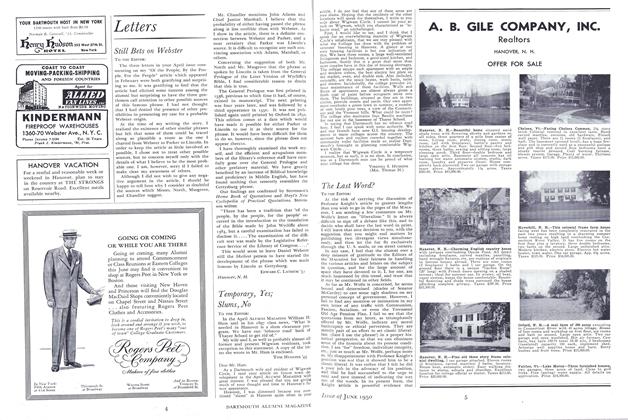

"HE REACHED HIGH AND PUT THE CAPSTONE UPON HIS FAME." So the Rev. Dr. Parker of Boston described Daniel Webster's address of January, 1830 (depicted in this Fanueil Hall p.mt.ng by Healy) which was made in answer to Senator Hayne's attack on New England. It was then that Webster used the words which later found their echo in the Gettysburg Address.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

February 1950 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Article

ArticleBack to Hanover in December

February 1950 By WILLIAM H. HAM '97 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1905

February 1950 By ROYAL PARKINSON, GILBERT H. FALL, FLETCHER A. HATCH -

Class Notes

Class Notes1943

February 1950 By ELMER G. STEVENS JR., STANTON B. PRIDDY, THEODORE R. HOPPER -

Class Notes

Class Notes1936

February 1950 By NORBERT HOFMAN JR., JOHN E. MORRISON JR., ROBERT L. PATERSON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

February 1950 By TRUMAN T. METZEL, COLIN C. STEWART, 3rd, LEON H. YOUNG JR.

EDWARD C. LATHEM '51

Article

-

Article

ArticleDoctors' Nemesis

October 1940 -

Article

ArticlePublic Life

DECEMBER 1996 -

Article

ArticleChapter Six: Taking Winter Carnival by Storm

APRIL 1999 By "Mom" -

Article

ArticleSoccer

OCTOBER 1966 By DICK BALDWIN -

Article

ArticleInvesting in Brainpower

Nov/Dec 2003 By Kate Lilienthal '88 -

Article

ArticleThe Musical Comedy "Double Trouble"

May 1929 By Phil Sherman