WHEN I left home and started falling out of planes with the U.S. Army paratroopers, my mother always warned me to wear my rubbers and keep the top button of my coat collar fastened at all times in that windy air between the plane and the ground. Nothing would happen to me then, she said, and I would always be healthy. And I guess she was right because I never picked up more than a small bruise. When I came to Dartmouth I was the recipient of the same advice— mother threw in a pair of ear muffs this time along with the rubbers and an extra large top button on the overcoat. She warned me about the slushy spring weather, the February frosts, the draughts in classrooms, people with colds, and wound up by handing me a bottle of Father John's medicine. She kissed me, said goodbye, and I was off to the bitter north, feeling the bottle in my pocket and wishing it were something else.

But all the medicine, the overcoats, and other protective accessories didn't do me a bit of good the other day when I slid into third base and found that I had seriously pulled my knee out of joint. My myth, my dream was shattered; and after I was fully convinced that I would have to submit to medical care, I packed up all pertinent belongings, got a haircut, said goodbye to my friends, and hobbled toward Dick's House expecting the worst.

Now, don't get me wrong—l think Dick's House is a fine idea, but they ruined my record. I'd never been confined there before, I'd never been told to put out the light at nine o'clock at night and go to sleep after having lain in bed all day, I've never had thermometers jammed down my throat every two minutes by bustling nurses who bounced gaily into the ward every morning, I've never been asked so many personal questions about the history of my bowels—in all, I've never been so completely domineered by women.

About the third or fourth day I registered a complaint and someone put a thermometer in my mouth to shut me up. My predicament centered around my being restricted to only one trip a day to the bathroom. Dr. Stuart Russell, Instructor in Orthosurgery at the Medical School, had given this advice to me and Ed Johnson 53. freshman from Alexandria, Virginia. Ed had also injured his knee while scrimmaging in varsity football practice. Our problems were the same, and we spent long hours deliberating about the reconciliation between the relatively high-powered diets of applesauce, prunes, and more prunes and the one trip a day. At breakfast along with the opening dish of prunes was a side order of juice, which tasted remarkably like something we'd just tasted. At noon there would be fruit salad (a small leaf of lettuce covered with prunes), and after the main course there would be prune pudding. At the evening meal they went easy on us, submitting for our inspection a prune pie or cake, but at no time did we discover that they had slipped anything into the soup; and so of course we spent long hours tippling the liquid, and rejoiced in the hope that there was still one sacred spot in the dietitian's heart. Needless to say, we hired a pair of community crutches, pointed out that the TaftHartley Act had something in it about an eight-hour day, and made the switch to a new bathroom schedule.

But the treatment is the best and we know it. However, being cooped up in a hospital ward during a Hanover spring when we can look out and watch our compatriots heading for the golf course is not exactly conducive to serene thoughts. For occasional diversion some of our more active cohorts would stick their thermometers up against light bulbs or under radiators. This would keep the nurses on the run for a while, and when the excitement died down we all would feel a little better.

Nevertheless, the nurses never seemed to mind. Miss Lois Dunn, house mother at Dick's House, was very charming. She and assistant house mother Margaret Petrikin made frequent trips through all wards and rooms, making sure that every Dartmouth man was well cared for and relatively assured of survival. When we needed our backs rubbed we'd call for nurse Priscilla Powers, while Catherine Murphy, possessor of the stiffest left hook at Dick's House, handled the pulse and thermometer department. I feared Nurse Alice Netsch, who applied the hot packs to my knee, the most; if at first the hot packs were too hot to hold, she would smile, drop them on my knee, and ask me how I was getting along. I would gasp and hope for quick recovery.

Probably the saddest part of being at Dick's House is the parting goodbyes, the farewells to those left behind. In my case it was difficult because I was saying goodbye to Ed Johnson, who was left alone in the ward over the Green Key weekend. I couldn't do this without feeling like an absolute heel, but the nurses kept pushing me and so I had to tear myself away.

Ed's case was peculiar. After a Saturday scrimmage, he and two other gridiron specialists were sent to Dick's House for Xrays of possible broken bones. One came down in a car while Johnson wheeled in the third in a wheel chair. Everyone was groaning in severe pain—everyone except Ed, who just smiled. When the results were posted all three were dismayed to find that Johnson had suffered a knee injury which would confine him to bed for nine or ten days while the others were set free and told to walk back and resume classes.

So, that's our Dick's House. Ed and I are free now, but we miss the orders and the nine o'clock curfew. We miss the night nurse who used to come around at three in the morning, wake us, and ask whether we were sleeping well. We miss Dr. Staples and Dr. Howe, who did strange things to our legs, and we miss the Green Key emissary Mike lovenko '51 who came around on Sunday night with ice cream. We miss them all, but probably more than anything else, we miss the prunes, the prune juice, the prune cake and pie, and even the prune I once found at the bottom of my coffee cup.

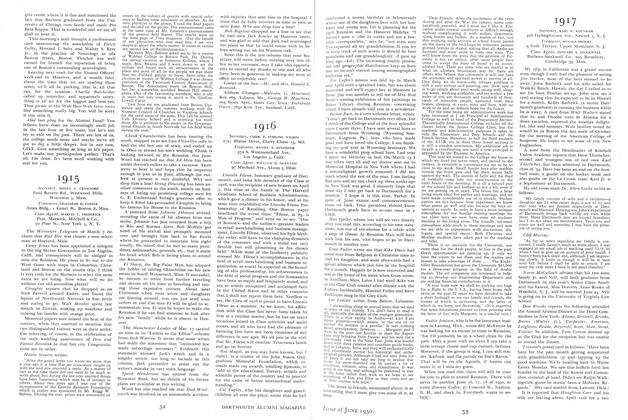

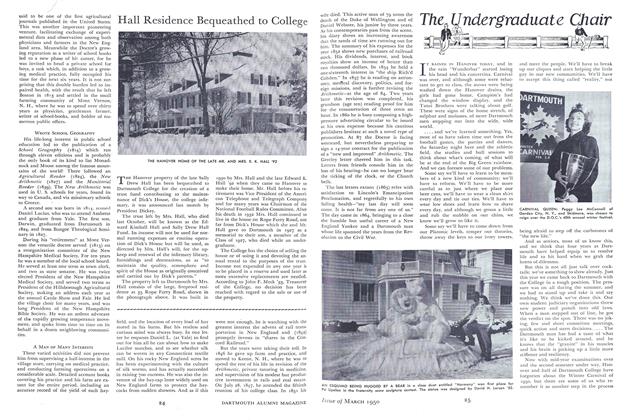

BILL MULLIGAN '50, Undergraduate Editor of the Alumni Magazine, whose final installment of "The Undergraduate Chair" appears in this issue.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTop Television Man

June 1950 By ROBERT R. RODGERS '42 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

June 1950 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

June 1950 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, EDWIN C. CHINLUND, GEORGE B. REDDING -

Class Notes

Class Notes1937

June 1950 By ROBERT C. BANKART, ARTHUR H. RUGGLES JR., ALAN W. BRYANT -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

June 1950 By TRUMAN T. METZEL, COLIN C. STEWART 3RD, LEON H. YOUNG JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1916

June 1950 By CMDR. F. STIRLING WILSON, DANIEL S. DINSMOOR, WILLIAM H. MCKENZIE

Bill Mulligan '50

-

Article

ArticleTHE HANDWRITING ON THE WALL

December 1949 By Bill Mulligan '50 -

Article

ArticleREASONS FOR POLL

December 1949 By Bill Mulligan '50 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

January 1950 By Bill Mulligan '50 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

March 1950 By Bill Mulligan '50 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

April 1950 By Bill Mulligan '50 -

Article

ArticleMilestones

April 1950 By Bill Mulligan '50