DARTMOUTH'S hopes for eventual elimination of discriminatory clauses from fraternity constitutions have gone another step forward. For some the step is a big one; for others, who would provoke action by a fast and decisive break, it is insignificantly small. But regardless, the student body has manifested a sense of democratic responsibility.

In a previous referendum this year, men of Dartmouth overwhelmingly voted to abolish restrictive clauses. Taking their cue from this, the Undergraduate Committee on Discriminatory Clauses went to work, and in early January recommended that "the Undergraduate Council, by April 1, 1952, should withdraw the privilege of participating in any fraternity competition from those fraternities whose constitutions restrict or might be interpreted to restrict membership because of race, religion, or national origin."

But for most, this was too sharp a break from the center of the road, and both the College and the fraternities would take a beating. First, it would mean that half of the fraternities at Dartmouth would be dropped from the intramural leagues. Going one step further, it would mean that men pledging fraternities would have to make the choice between participating in intramural activities or confining their athletic efforts to variations of the elbowbending exercise. And college spirit would lose out; fraternities winning intramural championships would care only halfheartedly about winning. The Dartmouth spirit would have taken a step in the wrong direction.

And so after heated debate the proposal was tempered and revised to read that the Undergraduate Council, by the end of each school year, shall review the efforts undertaken by those fraternities whose constitutions restrict or might be interpreted to restrict membership "

Clarifying the "review of efforts," the proposal went on to state that "if it can be established that any fraternity has not exhausted all possible means of eliminating such clauses short of dropping national affiliation, the Undergraduate Council shall withdraw all recognition of that fraternity which does not satisfy the above requirements, this resolution to take effect immediately."

The second proposal was drawn up by a group of men who felt that the original proposal would only force the fraternities affected to drop their affiliation or make those fraternities that had to remain national because of economic reasons so weak that they would cease to be as integral a part of Dartmouth as they have in the past.

The third proposal supported the "no action at this time" theory, and with these three proposals to mull over the wheels started to turn toward final resolution.

The Undergraduate Council called an open house session in Dartmouth Hall on Wednesday night, February 22. Here all three views would be aired and clarified for all interested in the referendum.

But it was a poor showing. Less than two hundred students put in an appearance, and before the meeting had ended the greater part of this group had left the scene of action. Steve Pollak 50 championed the first proposal which would make the complete break. He would give the fraternities two years to take action, and then resort to ostracism for those who had lagged. Steve contended that Dartmouth has plainly demonstrated that there is no place for discrimination on the campus and that the time has come for a decisive divorce from any policy which would entertain softpedaling platitudes. A break with the national fraternity was preferred over what he believed would be long-term conciliation. Steve felt that there was growing strength in numbers and that Amherst, Michigan, and NYU were riding his bandwagon. If enough pressure were brought to bear by the students of America acting as a group, the tide might become too great for the national organizations to ignore.

Bill Pulley '50 went to bat for the second proposal and although he tended to beat around the bush and repeat himself, he finally managed to give the audience a well-defined outline of his position. For Bill a complete break would do nothing. Pulley, a member of Phi Delta Theta, stated that if his fraternity were to break away and become a local organization, his national fraternity would simply shrug their shoulders and cross the Dartmouth chapter off the list with no more than a grunt. Bill maintained that he was looking farther ahead, that his proposal, if given a chance, would prove to be the answer in the long run. First, he maintained that it would give each fraternity a chance to exert its influence at each regional conference in an attempt to gain support for collective action and forcing a vote on the issue. Secondly, each fraternity could influence its national conference in much the same way it could its regional. Thirdly, each fraternity would be able to send petitions to all chapters of the national, stating attitudes and future aims; and last, could create alumni support by pressing the problem before them in the form of newsletters. Pulley's arguments were valid, but all agreed that it looked like an extremely long haul.

The last speaker of the night was Jim Stevens '50, who urged that the Undergraduate Council take no action at this time. He claimed that since all fraternities had gone on record as having been opposed to charter restrictions, a harsh proposal like Pollak's might be too much for the nationals to take in one gulp. He asked that since many fraternities on campus had approached their national organizations concerning the removal of discriminatory clauses and had been denied action, what good would it do to aggravate the condition? Coercion from the College, he added, would do more harm than good. Jim claimed that neither proposal was satisfactory and that "fraternity charters will be changed as a result of internal and external pressure on fraternities."

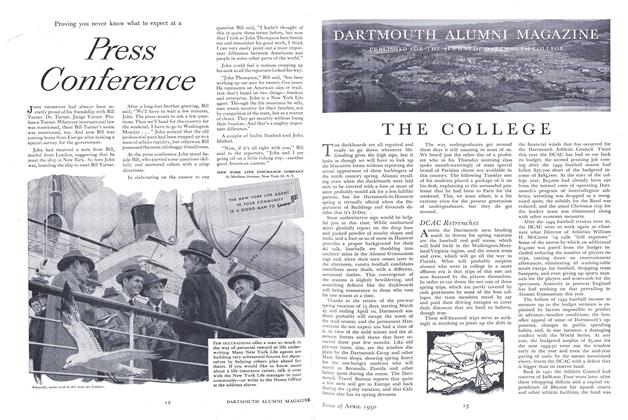

When the smoke cleared after a student referendum on March 1, Pulley's proposal, which incidentally had been endorsed by the Interfraternity Council, emerged as the answer after six violent weeks of tense emotions and student soapboxing. The winning proposal received 1354 votes, 110 above the required majority. Ninety percent of the student body was reached by the referendum, 2487 out of a possible 2760 ballots being tabulated. Proposal number one pulled in second with 885 votes, while Jim Stevens' third proposal claimed a small 248 count.

It is now the responsibility of the Dartmouth student government to clarify just how they will "review" each fraternity in order to determine whether or not Big Green fraternities are exhausting "all possible means of eliminating such clauses, short of disaffiliation with their national organization." If the Undergraduate Council sets up a stiff and sure law with exact requirements, proposal number two could be a moving force. If, however, the reviews fail to adhere closely to a hard and fast plan, discrimination will be with us long after we, the chief proponents of the issue, have left the campus.

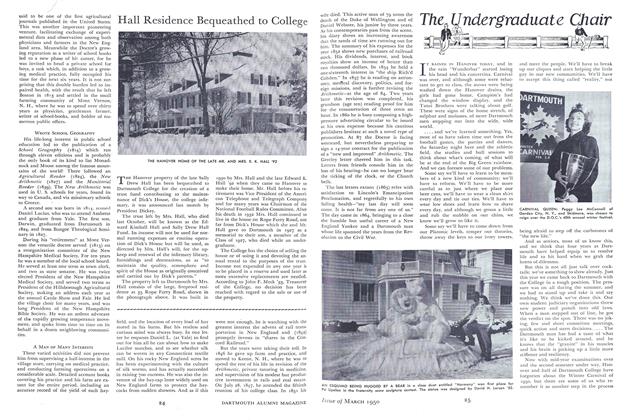

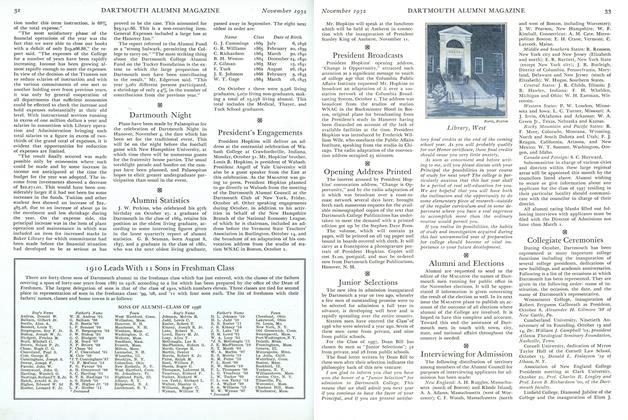

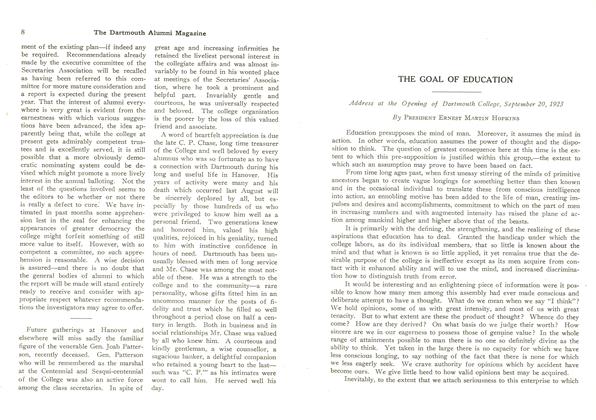

A STUDENT POLL RENDERS AN IMPORTANT VERDICT: A referendum on whether to eliminate, check, or ignore restirictive clauses in fraternity charters elicited a voting turnout of 90% of the undergraduate body on Feb. 28. Football captain Paul Staley '51, seated at a table in Thayer Hall, recorded the vote of Bill Dey '50, while other interested students await their turn to vote. The second proposal won.

"Immediate action . . complete breakif necessary" —Proposal No. 1 by Steve Pollak '50.

"No action at this time"-Proposal No. 3 by Jim Stevens '50.

"Ours is a long-run proposition" - Pro posal No. 2 by Bill Pulley '50.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleIS TITO COMMUNISM'S LUTHER?

April 1950 By JOHN CLINTON ADAMS, -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

April 1950 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Article

ArticleTHE COLLEGE

April 1950 By C.E.W. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1905

April 1950 By ROYAL PARKINSON, GILBERT H. FALL, FLETCHER A. HATCH -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

April 1950 By TRUMAN T. METZEL, COLIN C. STEWART 3RD, LEON H. YOUNG JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

April 1950 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, EDWIN C. CHINLUND, GEORGE B. REDDING

Bill Mulligan '50

-

Article

ArticleTHE HANDWRITING ON THE WALL

December 1949 By Bill Mulligan '50 -

Article

ArticleREASONS FOR POLL

December 1949 By Bill Mulligan '50 -

Article

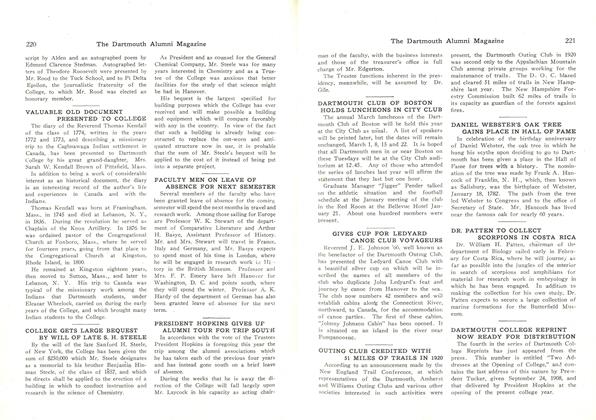

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

January 1950 By Bill Mulligan '50 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

March 1950 By Bill Mulligan '50 -

Article

ArticleMilestones

April 1950 By Bill Mulligan '50 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

June 1950 By Bill Mulligan '50

Article

-

Article

ArticleDANIEL WEBSTER'S OAK TREE GAINS PLACE IN HALL OF FAME

February 1921 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Night

November 1932 -

Article

ArticleStewart Elected Emeritus

October 1943 -

Article

ArticleLandlocked Women Skippers Find Smooth Sailing

September 1995 By Brad Parks '96 -

Article

ArticleTHE GOAL OF EDUCATION

November 1923 By ERNEST MARTIN HOPKINS -

Article

ArticleCleveland

February 1960 By RAYMOND M. BARKER JR. '52