Unless Freedom of Thought, Inquiry and Dissent Is Kept Unfettered We Will Go Down, Great Issues Speaker Warns

ONE OF THE most astonishing phenomena of our time is, I think, the perversion of the term free enterprise, the effort to monopolize it for and to limit it to the realm of economics. What is particularly astonishing about this is that those who are peculiarly insistent upon what they call free enterprise in the political and economic realms are, for the most part, those who are most blind to the real significance of the concept and to the dangers which threaten it today. Given our kind of people, with our history and our traditions, free enterprise is essential to prosperity, to security and to progress. The free enterprise that is essential, however, is not the narrow enterprise of rugged individualism; it is, above all, free enterprise in the intellectual realm. Freedom, progress, private initiative, all these things are not products of a peculiar kind of economy. They are antecedent to economic progress. Freedom does not flow from private enterprise; private enterprise flows from freedom. Freedom is not a luxury we can indulge ourselves in if we have security. Security is something we may hope to achieve if we have freedom. It was, after all, the free nations of the world, Britain and America, that survived in the two great wars of the Twentieth Century, and those who rejected freedom that went under.

Now all this seems obvious enough, yet we are in danger of losing sight of it as we lose sight of so many things that are obvious. I need not rehearse to you the story of the current threat to freedom of thought, expression, inquiry, criticism, dissent, in philosophy, in education, in economics, in politics and in so many other fields. That has been, I understand, the substance of the recent lectures in this course. Nor need I emphasize to you that threats to freedom of inquiry and of criticism are dangerous. They are dangerous for many reasons, and they are abhorrent to us for many reasons. They are dangerous and abhorrent because they violate those great traditions of freedom that are written into the constitutions state and federal and, more important, written into our hearts. They are dangerous because they violate that dignity of the individual so quintessential to our way of life, so basic to the philosophy of Western Christendom. But these again are, I think, in the realm of the obvious and I do not want to emphasize them anew.

Indeed, it may well be argued that in a time of great danger we should not be too sensitive about individual rights, or about human dignity for that matter. After all, it can be said, and with some justice, that those who threaten us care nothing for human rights or for dignity. After all, it may be said, a society that can demand the lives of its young men can demand some of their privileges, perhaps their freedoms. After all, it can be said that if our society goes under, these philosophical concepts will be of interest to the antiquarian only. And there is, I think, some particle of justice in these considerations. It is because these considerations are at least debatable that I want to put to you the case for freedom of inquiry and criticism and dissent freedom for the non-conformist, freedom for the rebel on other grounds: on grounds of pragmatic consid- erations.

One of the astonishing developments of recent years is the tendency in this country to abandon pragmatic tests and embrace doctrinaire and speculative tests. More and more, in the last decade especially, we tend to judge things not by their consequences but by a priori standards. We tend increasingly to look at things not as to how they work but as to how they ought to work if we had our way with them. We tend to judge colleges, for example, not so much by what they do but by our ideas of what they're like. We tend to judge associations not by what they achieve but by the alleged views of their members. We tend to judge so important a matter as loyalty not by conduct but by our ideas of what loyalty ought to be. More and more this generation is putting its faith in gestures, in ceremonies of one kind or another—loyalty oaths, for example, or "I Am An American Day" parades. Our very politics are coming to be a vulgar competition in eloquence about loyalty and about patriotism, with rewards going to the most vociferous.

Now this is not an aside, although it may sound like one. It is, I think, a consideration central to our problem. For our concern for the preservation of freedom and of an atmosphere in which freedom can flourish is animated most strongly by considerations of consequences of what happens to us it's already happening if we begin to chisel away at the edges of these basic rights and activities. I make no apology for calling to your attention the significance of consequences of our conduct. It is thoroughly in the American tradition to consider that matter. I think we should all be more deeply concerned, right now, with the consequences to our security and I'm using that word in its very broadest sense: our ability to maintain ourselves and our values, to maintain the things we believe in in a world where they are threatened on all sides if we continue on our present course of penalizing non-conformity, of penalizing heterodoxy, of making it difficult, if not impossible, to discuss great matters of policy without incurring the charge of disloyalty....

I TURN now to a final consideration, one that seems to me of immeasurable im- portance to the functioning of democracy. I refer to the present assault upon the freedom of association and the rise, over the last decade, of the doctrine of guilt by association. Only those who are familiar with Old World history can realize how extraordinary the American practice of private association has been. In many ways it is the most remarkable and the most successful of all the practices of democracy. In the very beginning the founding of America came by the method of, voluntary associations: the Virginia Company, the Massachusetts Bay Company, and other companies. Almost all our major institutions are to this day voluntary organizations. A political party is a voluntary organization, unknown even to law until 1907, and wholly unknown to the Constitution. All of our churches are voluntary associations. Most of our colleges and many of our great universities are voluntary associations. Indeed, the characteristic form that democracy takes in America is the form of men and women banding together voluntarily to do things that need to be done. Sometimes this takes rather absurd forms. Vegetarians band together and stamp-collectors band together, and veterans of the blizzard of 1888 band together, and people who want to read Forever Amber band together in book-clubs, and so forth, but that is merely an absurd side of a very important principle the principle of doing things by voluntary association and organization. Now, for the first time in history, that principle is seriously jeopardized by the rise of the doctrine of guilt by association. There are some very interesting features in this doctrine of guilt by association that I want to call briefly to your attention.

The first interesting feature is that it is very much a one-way affair. Infection works only from radicalism to conservatism and never from conservatism to radicalism. One Communist infects a whole Republican organization but one Republican never infects a Democratic or Communist organization. At least so it would seem. It's rather extraordinary that we should confess the greater, more persuasive power of radical or Communist ideas than of conservative ideas in this assumption. Perhaps it's an assumption that fits the Puritan doctrine of the innate depravity of man, that the pernicious ideas always succeed in transmitting themselves, whereas the virtuous ideas never do.

The second interesting assumption about the doctrine is the assumption that we can, in fact, inquire into the beliefs of members of organizations we join. Superficially, it seems that we should do so, and, superficially, there seems to be some basis for the charge that people ought to be careful of the company they keep. "Birds of a feather," it is said brightly, "flock together." Well, sometimes they do and sometimes they don't. The point is that we do not in fact, and have never, in fact, and cannot, in fact, require men and women to be sure of the character of those who belong to organizations to which they themselves belong. We cannot do so with respect to churches; we cannot do so with respect to labor unions. It is absurd to suppose that no one joins the local church without first getting a list of members from his clergyman and investigating each of them. It is absurd to suppose that no one joins the Rotary Club or Kiwanis without hiring Pinkerton detectives to investigate the private lives and morals of all the members. It is absurd to suppose that anyone who comes to lecture at Dartmouth College, and thus affiliates himself sympathetically with this institution, inquires into the character of the trustees, the president, the faculty and the student body, before he associates himself with them. These things, in fact, are never demanded of the ordinary forms of association. They are not demanded of members in the American Legion. Nor is it supposed for a moment that any guilt attaches to the members of the Legion by sympathetic association with that Legionnaire, Senator McCarthy. They are not demanded of members of the American Medical Association or the National Association of Manufacturers. Only with respect to associations concerned with reform; only with respect to associations that may perhaps some-times quite justly be regarded as radical or Communistic.

Now these two principles of this policy should be kept in mind, but more important than these are the consequences of this policy of discouraging associations. The consequences are already with us. They are, in effect, that men and women simply cease to join things. It is dangerous to join if you never know who belongs to an association or who belonged to it in 1939. The easiest thing is not to join. That may seem a very simple thing in one instance isolated from others, but put them all together and you dry up the very roots of American democracy which functions through voluntary associations. The same principle which prevents you, or even restrains you, from joining some organization like the Society for Giving Free Milk to New Hampshire Children will prevent you, in the long run, from joining a political party.

Tocqueville, who saw most everything over a hundred years ago, put his finger on this as well, in his Democracy in America, where he has a remarkable chapter on voluntary associations in America. "When some kinds of associations are prohibited," Tocqueville wrote, "and others allowed, it is difficult to distinguish the former from the latter beforehand. In this state of doubt men abstain from them altogether and a sort of public opinion passes current that tends to cause any association whatsoever to be regarded as a bold and almost illicit enterprise. It is therefore chimerical to suppose that the spirit of association, when it is suppressed on someone point, will nevertheless display the same vigor on all others and that, if men are allowed to prosecute certain undertakings in common, that is quite enough for them to set about them. It is in vain that you will leave them entirely free to prosecute their business on joint stock account. They would hardly care to avail themselves of the rights you have granted them; and, after having exhausted your strength in vain effort to put down prohibited organizations, you will be surprised that you cannot persuade men to form the organizations you encourage."

This process, I repeat, is already under way. Every day it becomes more difficult to organize new associations, or to maintain old ones. Every day it becomes increasingly difficult to undertake any program of reform of any kind, or even of change. And as the impetus to association dries up, I repeat, democracy itself dries up.

Now, those who are responsible for the doctrine of guilt by association do not mean to attack democracy. They regard themselves as the champions of democracy. Those who paralyze the right of petition, for example, do not mean to whittle away at the Bill of Rights. They think of themselves as guardians of the Constitution. But they make it very difficult to sign anything. If we look at what is actually happening and what is bound to happen, we can see that these policies of threatening the right of association and petition do strike at the grass roots of democracy. But we cannot have our cake and eat it too. We can't have all the advantages of voluntary associations and yet threaten those who associate voluntarily if we don't like the associations.

Now WE HAVE been very busy, in recent months especially, calculating our resources and the resources of our potential or real enemies, and that calculation is going on all over the globe. Mr. Hoover has calculated and concluded that we do not have the strength to resist Communism anywhere but in the Western Hemisphere. Mr. Kennedy made the same calculation he made in 1940 and he's come up with the same answer. Mr. Taft has calculated and he, too, feels we dare not risk what we have, that our best policy is a defensive one. Actually, the situation, even the material situation, isn't nearly as black as the Hoovers, the Kennedys, and others paint it.

But it is not our superiority in atomic weapons that I want to speak of, or our industrial potentials. There is one all-important field where our superiority is, I submit, beyond challenge and where it is decisive, and that is that ours is a system of freedom—freedom of inquiry, freedom of criticism, and freedom of creation. Our science is unfettered. Our inventiveness is untrammeled. Our ability to think and inquire and criticize and resolve is still free. It is, literally, impossible to exaggerate the importance of this advantage. It is the one clear, indubitable advantage we have over our potential enemies. It is one we can count on if we can keep it. The nature of that advantage is, I think, clear enough. The Communist system is a closed system, as, in a sense, the Nazi system was. In Communist countries facts have to conform to preconceived ideas or so much the worse for facts. If biology does not justify Karl Marx or Lenin, then you get a new biology! If history does not justify Communism, you write new history that will! And so up and down the line. In the realm of music, for example, this may be merely a joke though I don't think it is but in the realm of science and the realm of political activity and the realm of economic development, it is the most serious thing conceivable. For this requirement that facts conform to the system of principles or ideas that are inflexible extends to the whole world of affairs. Just as there is no room in history for facts that do not conform to the Marxist version, so there is no room in political councils for diplomatic relations or for strategical decisions that do not conform to preconceived patterns. The Marxists are immensely powerful in all material things but they are prisoners of their own system, or, if you will, of their own power, and their Achilles heel is precisely here, that they cannot tolerate criticism, or dissent, or independence, or originality.

Now it is here that our superiority lies. By "our superiority" I do not mean just the Americans; I mean also the British, the French, the Scandinavians, the Swiss, if you will, the Low Countries. Because, if we are free, we can, if we will, avoid errors. We can experiment. We can try all things and hold fast to what is true, trying it over again from time to time. We can criticize, and Heaven knows we do. We can adjust and accommodate and compromise. We can air our grievances. Our scientists can follow where science leads. Our historians and our economists can follow the track of truth and arrive at conclusions that are reasonably sound. We are not committed to our mistakes. We are not committed to irreversible policies. We do not so far require that all our associates must agree with us one hundred percent, or insist that all who are not with us are necessarily against us. We are, however, in danger of doing just these things if we don't watch ourselves. By insisting upon standards of conformity and of orthodoxy, and by threatening all those who dissent or criticize, who give us unpopular advice, we are in danger of following what is, fundamentally, the totalitarian technique and the totalitarian philosophy, and that points, I think, to ultimate disaster.

Now, I do not say that only a society dedicated to freedom can win victories that would be nonsense. Soviet Russia is not dedicated to freedom, and she has won a good many victories. But I do say, without qualification, that a people like the American people, with its traditions, its history, its habits, its attitudes, its institutions of democracy, its degree of general enlightenment; given that kind of people, that kind of society only one dedicated to freedom can survive. Only if we actively encourage discussion, inquiry and dissent and heterodoxy, only if we put a positive premium on non-conformity, can we hope to solve the enormously complex problems that confront us. Only if we do this, can we enlist the full and grateful support of all our people and command the respect of our associates and allies abroad. Only in this way can we guard ourselves against errors that may be fatal.

If, in the name of security, we start hacking away at our freedoms freedom of the scientists, for example; freedom of the scholar; the freedom of the teacher and the student we will, in the end, forfeit security as well. If the commonwealth which all of us cherish is to survive and prosper, we must at all costs encourage free enterprise in the intellectual and spiritual realms as well as in the economic realm. I need scarcely add that our responsibility here is immense. Upon us rests, to a large degree, in this generation, the future of Western Civilization and Christendom. If by silencing inquiry and criticism we fall into error, the whole of civilization, as we know it, may go down with us. That is an immense responsibility for us to assume and it should give us pause. We must use all our resources and use them wisely. We have great resources, and of all, the greatest resources are in the minds and spirits of free men. These we must not fritter away. At a time when we are engaged in calculating our strength and the strength of potential enemies, listing our allies and the allies of the Soviet, it is not irrelevant to recall the closing lines of Wordsworth's sonnet, To Toussaint L'Overture: "...thou hast great allies; Thy friends are exaltations, agonies, And love, and man's unconquerable mind."

PROFESSOR COMMAGER ON HIS VISIT TO DARTMOUTH

PRESIDENT DICKEY HONORED BY NATIVE STATE: In recognition of his accomplishments as lawyer, gov- ernment official and head of Dartmouth College, President Dickey was cited as Pennsylvania Ambassador during Pennsylvania Week in 1950. Unable at that time to aitend the presentation ceremony in his native town of Lock Haven, Pa., President Dickey received his citation recently in Hanover at the hands of Miss Lois Dunn, House Mother at Dick's House, who is also a former resident of Lock Haven and who was chosen to make the presentation on behalf of the Lock Haven Chamber of Commerce. The citation of a distinguished former Pennsylvanian is made annually by the State Chamber of Commerce from nomina- tions made by local chambers throughout the state.

Professor Commager, one of America's most distinguished historians, closed the first semester of the Great Issues Course with the lecture we are privileged to present here in major part. His lecture was informally delivered January 23 and is printed, with only minor editing, just as it was recorded. Professor Commager's talk to the senior class concluded the section of the Great Issues Course devoted to Issues of Freedom. Preceding it were lectures on the roots of freedom, the changing nature of communism, internal security, freedom and communism in the colleges, and President Dickey's talk on academic freedom.

PROFESSOR OF HISTORY, COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

March 1951 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, EDWIN C. CHINLUND, GEORCE B. REDDING6 more ... -

Class Notes

Class Notes1905

March 1951 By GEORGE W. PUTNAM, GILBERT H. FALL, FLETCHER A. HATCH -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

March 1951 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate

March 1951 By PETE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

March 1951 By TRUMAN T. METZEL, COLIN C. STEWART 3RD, LEON H. YOUNG JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917

March 1951 By KARL W. KOENIGER, DONALD BROOKS, HOWARD A. STOCKWELL

Article

-

Article

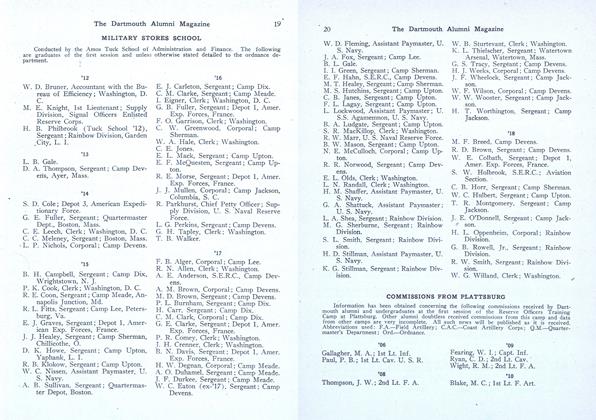

ArticleCOMMISSIONS FROM PLATTSBURG

November 1917 -

Article

ArticleGleanings

December 1934 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

November 1941 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

ArticleGood Olde Roughhousing

SEPTEMBER 1987 By Jim Needham -

Article

ArticleThe Story of Buster Jig

December 1988 By R.H.N. -

Article

ArticleFaculty

DECEMBER 1972 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40