I HAVE frequently had the opportunity of saying this final word at commencement exercises but I confess never without embarrassment. You have just grasped the coveted parchment, symbol of your emancipation from all tutelage, and now you should listen to one more final word of advice from an old man to young men. It seems a futile proceeding since young men are as inclined to disregard advice as old men are to give it. Furthermore, it is a somewhat dangerous enterprise, for if there is such a thing as a friction and tension between the generations, why should I increase it at the last moment?

Perhaps you know the words of a modern poet, Witter Bynner: Said the old men to the young men, "Who will set us free?" Said the young men to the old men, "We." Said the old men to the young men, "It is finished; you may go." Said the young men to the old men, "No." Said the old men to the young men, "What is there left to do?" Said the young men to the old men, "You."

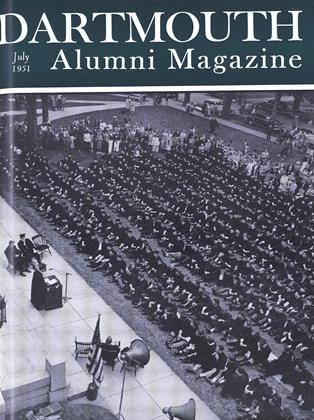

Dangerous as the proceeding is, however, in saying this final word of advice, there is a deep instinct in our college ritual that provides for it since this is such a significant milestone in the life of educated young men. I couldn't help but observe as I watched the proceedings of these commencement exercises in these past two days, that a graduation in an American college is in some respects more significant than the graduation from any other educational institution because, though we may as American colleges not be altogether unique, as educational and cultural institutions we have, in a way, established a uniqueness compared with the colleges and universities of Europe' in that we are a more completely integral community, the parting from which is more difficult than from the ordinary educational institutions.

Commencement is a significant milestone at which very properly a word may be said in grateful appreciation of the past and offering a discriminate view of the future. One of the most frequent words at commencement exercises is to admonish young men to continue to grow in the way that they have grown in knowledge and discernment during their college years. This is not an unnecessary word considering that one of the weaknesses of our college education in America is that it doesn't altogether take; that is to say, we do not maintain the intellectual and spiritual enthusiasms of our college years quite as successfully, in later years, in America as do some other cultured nations.

But it isn't about this continued growth that I want to speak to you, but about a contradictory subject: namely, the problems of life which are not solved by growth at all, but by recognizing the lim- its of growth. Have you ever observed that one of the most interesting aspects of human existence is that our world grows more rapidly than we can possibly grow, and therefore there is no way of solving our relationship to our world by growth alone, whether by intellectual, or moral, or solid growth? It is not possible to do this because our world expands so much more rapidly than we grow.

A little infant is the most impotent of all creatures, and yet compared with us, more powerful than we will ever be; for the infant is the center of its world not only in its own esteem but in the atmosphere created about it. The infant is the center of a world which is organized for its protection and for its nurture. The human animal has the longest period of infancy and grows through many nests and many homes; we grow and grow but all the time our world is growing more rapidly than we are. You have reached the point where you are being shoved out of the final nest of human infancy and are moving into a world which you will not be able to control at all. This is a paradoxical aspect of human existence, that some of the deepest problems of life must be solved not by growth but by dying to self in order that we might truly live. A text would seem appropriate on this Sunday morning and my text is, "Except the corn of wheat fall into the ground and die, it abideth by itself alone; but if it die, it will bring forth much fruit."

Consider our relation to other selves. Here is this little private self of ours which needs others. The more human civilization develops, the more we need other people to complete our life, and yet if we merely try to use others to complete our life, we fail. The significant thing about these mysterious other selves who impinge upon our life is that they are on the one hand the stuff by which and in which we must be completed, and they are on the other hand the final limits of our personality which we dare not violate. Unless we die for them, give ourselves to them or are taken in by them, we cannot live. Many of you will in the next months, certainly in the next years, found—some of you have already founded—the most basic of all human communities, the family. Every- thing that might be said about life, in the relationship of community, is symbolized in this family. As men and as women we symbolize in our natures the fact that we cannot live to ourselves alone. A man needs a woman, a woman needs a man; they are completed in each other, but they cannot use each other to complete themselves, nor can they form the community of the family merely by calculated mutuality, for calculated mutuality turns very easily to calculated selfishness. There must be some abandon in this human relation, and the abandon of one self to the other in this most primordial of all communities is a symbol of what makes community one of the highest levels of human life. We must die to self in order truly to live. This is true not only of our relations with other individuals; it is also true of the pattern of our individual life, of the patterns of human existence, the pattern of our nation, the pattern of civilization. Isn't it marvelous that on the one hand this human self of ours is so unique and is so free, and in the mystery of its freedom and uniqueness stands outside of itself, its nation and its world as a responsible self. Yet on the other hand this same self is related indeterminately to destinies which it cannot control, wide destinies of nations and of cultures.

I think one could make one criticism of academic training. Almost inevitably be- cause of a certain preoccupation with minutiae and a certain passion for coher- ence, it is more difficult for the academic community to understand what poets and men of affairs understand—namely the paradox of the self which is so very free and so very final and yet on the other hand is constantly subjected to all the des- tinies of nations and civilizations that are not of its contriving and that it cannot control. We are not the masters of our destinies, and there is always the point where our destiny has to yield to a wider destiny. We cannot be ourselves until we have made that submission.

I belong to an older generation that graduated from college before these tragic years. I regarded myself as a Christian young man, but one of my favorite poems was a very pagan poem which I thought wonderful; but its thesis has been refuted by the tragic wisdom of our years. You may remember Henley's Invictus: Out of the night that covers me, Black as the pit from pole to pole, I thank whatever gods may be For my unconquerable soul.

In the fell clutch of circumstance I have not winced nor cried aloud, Under the bludgeonings of chance My head is bloody but unbowed.

It matters not how strait the gate, How charged with punishments the scroll, I am the master of my fate: I am the captain of my soul.

The theme is rather robustious but not very true. Up to a point we are the masters of our destiny. But think of this college generation as against my college generation, how your private destiny and your private and justified ambitions must be qualified and brought under the vast destinies of our nation, of our whole culture and civilization. And if you should insist too much upon the mastery of your own destiny, you would suffer shipwreck within these vast patterns of history in which you must play your part. In fact, we stand in an historic situation so tragic that we may question whether the emphasis upon happiness as one of the aims of life is really justified, and whether we in Amer- ica have not made a mistake in our constant emphasis upon happiness. We have been living for so many decades in a world of infinite possibilities that we thought that the center of our destiny was identical with the center of the destiny of the world.

Happiness may be defined as an inner concomitant of any neat and nice harmony of life. Wherever there are neat and nice harmonies, frictionless harmonies, there is happiness. All of us want happiness and all of us enjoy it from moment to moment. But there is not very much happiness in the world. There can be joy, but not sustained happiness since there are not very many neat and nice harmonies in life. Life is full of incongruities and incoherencies, and the final possibility is not happiness, but joy, touched with sorrow, growing out of sorrow, coming out of the death of the old self and the creation of a new self that has surmounted the incongruity between its own destiny and the nation's and the generation's destiny.

Our own nation is a wonderful collec- tive symbol of this curious contradiction between the self and its expanding world. We can see more clearly in the collective destiny of our nation what we ought to see in every individual life. This nation with its very recent infancy, with its tre- mendous growth toward maturity, with its sudden immersion in global responsibility, this nation more powerful than it has ever been, more powerful than any nation has ever been, is now in the situation of being less able to do what it wants to do than when the nation was weak. It has become powerful but its power has interlaced its destiny into the destinies of mankind so that we are in the terrible, the awful and wonderful predicament, that we cannot save ourselves without saving a civilization, and we cannot even save ourselves if we make the saving of the the calculated policy of our own survival. Now we see that we must die as a nation that thinks only of itself, in order that we might truly live. Perhaps one of the reasons why there has been more hysteria in our country than there should have is because there have been some men lacking in wisdom who thought that our peculiar situation was due to the weakness of this or that statesman. Mistakes undoubtedly have been made and will continue to be made, but our situation is not due to either the errors or the contrivance of statesmen. It is a final and perhaps a belated revelation of the very law of human existence. History has caught up with the American people and all of this young generation, and we know now that we cannot solve the problems of either individual or collective life by indeterminate expansion, but rather by yielding to destiny and by accepting life in all of its beauty and all of its terror.

No matter how ambitious and competent and intelligent and wonderful your gifts are, no matter how greatly your life becomes significant, you will ultimately discover through the wisdom of experience (which is a kind of wisdom that cannot come out of the best academic institution) that your life will remain fragmentary. Nothing that is worth doing can be accomplished in your lifetime; therefore you will have to be saved by hope. Nothing that is beautiful will make sense in the immediate instance but only in the very ultimate instance; therefore you must be saved by faith. Nothing that is worth doing can be done alone, but has to be done with others; therefore you must be saved by love.

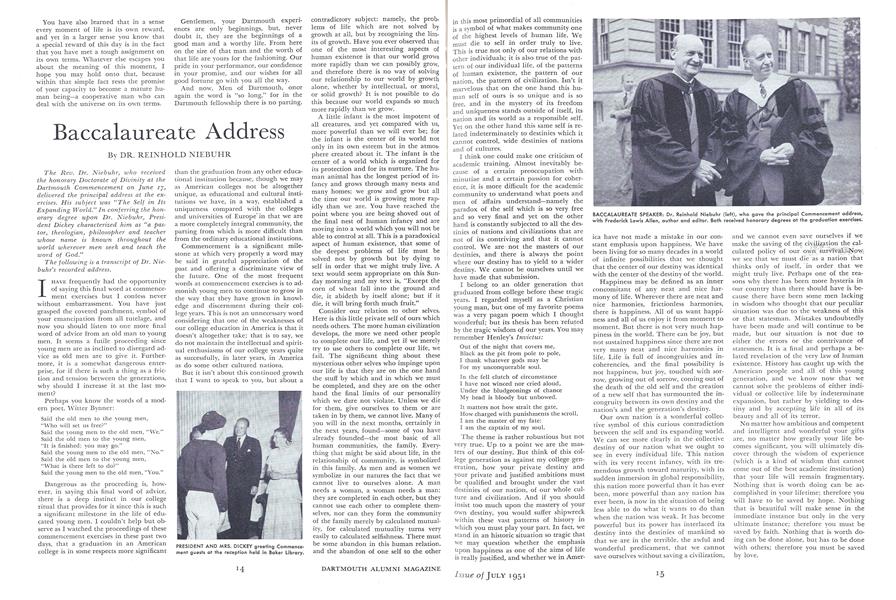

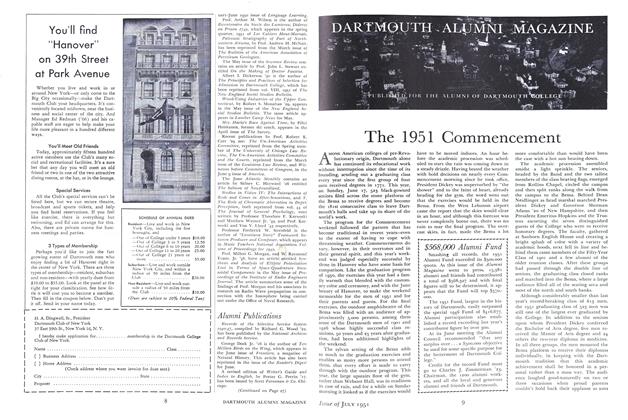

PRESIDENT AND MRS. DICKEY greeting Commence- ment guests at the reception held in Baker Library.

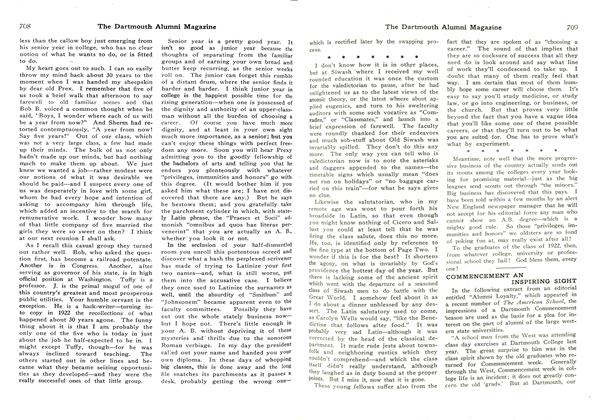

BACCALAUREATE SPEAKER: Dr. Reinhold Niebuhr (left), who gave the principal Commencement address, with Frederick Lewis Allen, author and editor. Both received honorary degrees at the graduation exercises.

The Rev. Dr. Niebuhr, who receivedthe honorary Doctorate of Divinity at theDartmouth Commencement on June 17,delivered the principal address at the exercises. His subject was "The Self in ItsExpanding World." In conferring the honorary degree upon Dr. Niebuhr, President Dickey characterized him as "a pastor, theologian, philosopher and teacherwhose name is known throughout theworld wherever men seek and teach theword of God."The following is a transcript of Dr. Niebuhr's recorded address.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

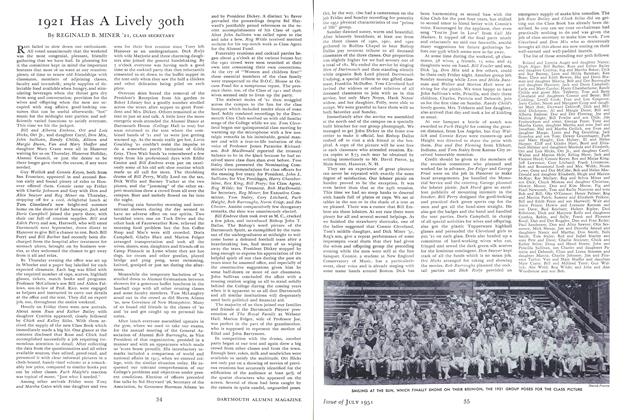

Class Notes1921 Has A Lively 30th

July 1951 By REGINALD B. MINER '21 -

Article

ArticleThe 1951 Commencement

July 1951 By C.E.W -

Class Notes

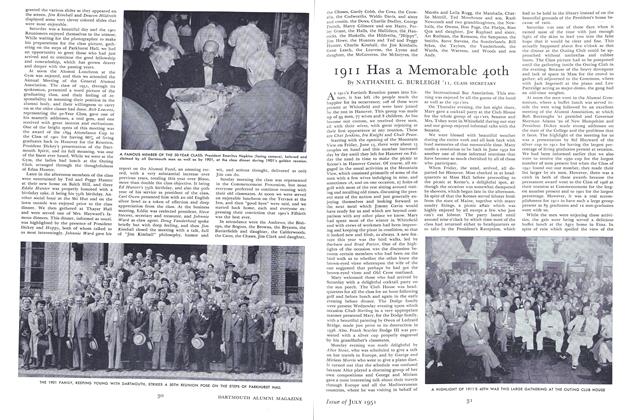

Class Notes1911 Has a Memorable 40th

July 1951 By NATHANIEL G. BURLEIGH '11 -

Class Notes

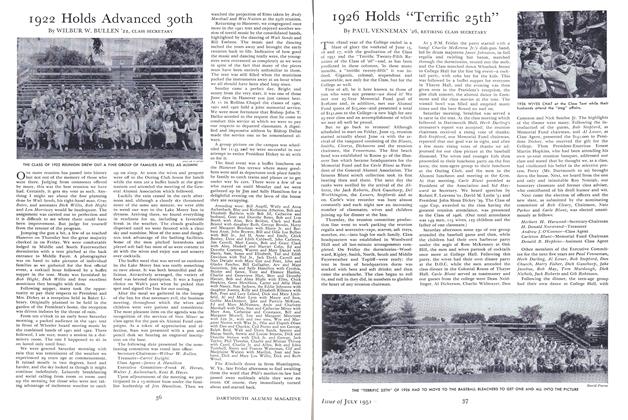

Class Notes1926 Holds "Terrific 25th"

July 1951 By PAUL VENNEMAN '26 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1941 Weathers Its Big 10th

July 1951 By FRANK M. HALL '41 -

Article

ArticleThe Fifty-Year Address

July 1951 By ROBERT F. LEAVENS '01