I WANT first to express my very deep appreciation of the high honour done to me by Dartmouth College in making me a Doctor. I am sure that when I say this I speak not only for myself but for all of us whom you have honoured this morning. As you know, I come from the academic world and was a student and then taught for ten years at Oxford. My University in England has an ancient and honourable history and I am proud to belong to it. My College in New England, of which I am proud to be a member, also has a long and distinguished tradition. Both Oxford and Dartmouth have achieved renown in the study of the Liberal Arts. Out of both there has flowed a stream of men developed and enlarged in character and intellect by their student years.

I am sure that here, if I were to ask President Dickey how many students there are in the College, I should not get the reply I received from another president of another college. Then the reply was "About one in a hundred." Yet I have noticed with pleasure that your traditions allow room for exercises which are not wholly the product of the higher thought. In your very early days, I understand, you had to move from another place to this lovely campus because the attraction of the local apple orchards was so great that the Connecticut farmers thought they would not be able to make any cider. These little differences between town and gown are part of the early history of a really distinguished and ancient seat of learning. We had them in Oxford in the Middle Ages. Indeed, it was after a major dispute of this nature that a group of students, according to our Oxford story, went off to find a less dangerous place, where the pulse of life was slower, and founded Cambridge.

This year in Britain we have a young Queen upon the throne, Queen Elizabeth 11. As we look forward to the years of her reign with cheerful anticipation and the confident belief that she will bring increasing vigour and prosperity to our island, we cannot help looking back and remembering again her great ancestor, Queen Elizabeth I, and the days of the first Elizabethan Age. We British have a strong sense of our history. When we look to the future we often cast a glance for guidance to the past. In 1940, when Hitler's armies massed at the invasion ports on the French coast and the outlook was grim, we found ourselves thinking of Philip of Spain and his Armada and how it was vanquished, and of Napoleon whose troops sat in their cantonments for two years at Boulogne and never set foot on the barges he had assembled for the invasion of England. From these thoughts we drew courage and inspiration: what had not happened in the past was not going to happen in the future. So now today, when we look back to the age of the first Elizabeth, it is not to sigh for glorious days long past, but to find in our present recollections of those days a pattern and an inspiration for the future. In this we are romantics.

The other day Mr. A. L. Rowse, the distinguished British historian, was speaking on this theme and wondering about a new Elizabethan Age. He pointed out that our situation resembled that of our 17th Century ancestors because we are conscious of having faced and come through a great danger and having triumphed against heavy odds. But then he went on to make a contrast. In those days emphasis was on creation, whereas now it seemed to be on criticism. Too many people, he complained, spent their time criticising what was being done or talking about what could be done, but not trying themselves.

What have we to say to this, we who are educated in the Liberal Arts? I can well remember being told when at Oxford that the great point of a liberal education was that it sharpened and developed one's critical faculties. Is it true that our university years make too much for self-conciousness and sophistication and that when we have finished, because we are critical, we are less rather than more able to create?

The world we are living in is obviously in great need of men with a positive turn of mind, an affirmative attitude to life, the power to create in thought and action. So many things have happened so fast in this 20th Century. It is the century of the automobile, the tank and the aeroplane. It is the century of radio, television and radar. The world is divided by clashing ideologies. The peoples of Asia are on the move and have taken over from us, with consequences we cannot yet foresee, the concept of the nation state and made it their own. As antagonisms of ideas and systems have grown stronger, so the world, in terms of communication and movement, has shrunk. Today, whether we like it or not, security is indivisible and we are all involved, each from our own angle, in the same complexities, difficulties and dangers. There is great need of patient and creative thinking, of persistent and constructive action, if we are to make the best of our opportunities and transform the situation.

It is true that one of the most valuable products of a liberal education is a critical mind. But it is not true that criticism is always and essentially negative. To criticise, if we dig back to the etymological root, is to judge, and judgment can be positive as well as negative, constructive as well as destructive. All of us are confronted from our earliest days with a mass of impressions and perceptions. We absorb the tradition, prejudices and beliefs of the society to which we belong. Our experience is voluminous and infinitely varied, shifting and complex. Yet life is a series of actions and decisions, a few of them from time to time important and far-reaching in their consequences. An uncritical man is the slave of his accumulated experiences: he acts and decides from prejudice, habit or emotion. He does not use his reason to sift and order his beliefs so that he can know what he does and make a sound judgment of his course.

To my way of thinking a liberal education such as you have had is a prolonged course in the examination of experience. It examines one's beliefs and impressions, those of the society to which one belongs, those of the civilization which one inherits. In all the branches of your academic discipline, history, language, literature, philosophy, mathematics, natural science, this is what you have done. The process is critical through and through. It is to learn enough, to perceive sharply enough, to reason with valid logic. Then the wealth o£ experience can be mined and its precious ore extracted. A critical mind expressing itself in right judgment is a permanent possession and a trustworthy guide to the tangled situations of actual living for those who have undergone and mastered the liberal disciplines. They are accredited to the kingdoms of the human spirit.

Criticism is not just picking holes in what other people like to believe, any more than philosophy is just finding bad reasons for what people believe anyhow on instinct. The cynic and the sophist are not the true children of the Liberal Arts. For criticism and judgment imply standards, positive standards, standards of value in the light of which we criticise and judge. These are the lamps which light up the way, the lamps of life which Lucretius saw handed on by each generation to its successor in the race. In their light we explore our great inheritance and judge what to hold fast, what to build further and what to reject.

The inheritance of Western Civilization holds many things which a right judgment cherishes and uses. There is one insight, simple in statement and universal in scope, which I should like to name. You can find it in the first Chapter of Genesis. It echoes and is repeated through the thought and literature of every century. The story of the Creation ends with the declaration that "God saw everything that He had made and, behold, it was very good." It is a fundamental insight of Western Civilization that value and goodness can be realized in the world, that human striving and effort is not always and necessarily frustrated and hopeless, that what we do can make a difference: it has point to try to make things better. Here is the nerve of hope and all endeavor. In this belief over 350 years you have made the United States out of an empty and trackless continent. From this belief flowed the creative splendour of the Elizabethan Age. By this belief it is good sense to pursue the peace of the world.

There is another insight you will have found disclosed by your examination. Over the centuries men have discovered, and painfully worked out in practice, the truth that the State is made for man and not man for the State. Here is the insight of Magna Carta and the Bill of Rights in my country: of the Declaration of Right and the Declaration of Independence in your country. It is the foundation of democracy. It is the justification of the rule of law. It is the belief that every man has worth and dignity in himself. It is the belief that with his fellows he should so order the political structure that it provides for the development of persons, not the absoluteness of power.

Getting on for one hundred years ago the great Bismarck touched on a facet of our more recent experience and history. The most significant fact, he said, of the 19th Century was that Britain and the United States spoke the same language. His prescience has been proved in two world wars, when the United States and Britain with the British Commonwealth have stood together to resist aggression and uphold the life of freedom. In the friendly association of the English-speaking peoples lies the firm foundation for preserving the sanity of the world, and the citadel of freedom. Our two countries, yours spanning a continent and mine the focus of a commonwealth of nations, have a great contribution to make. By our traditions we both believe in the freedom that can make room for other people with a fair regard to their interests. We believe that a compromise of this kind is not cowardly but constructive. Our broad aims in the world are similar: we both seek peace, prosperity and stability for ourselves and for others. We believe in making an effort to get along together for we have faith in the power of reason and the force of argument. We reject the policies of those whose only argument is force. Because our broad aims coincide, we find profit in talking together and talking things out. We are not afraid to argue. Anglo-American relations are not endangered by this habit or by our occasional disagreement. The fact that we talk together when things worry us is proof of the vigour and strength of the relations between our two countries. In the pattern of our relations, the Anglo-American pattern, there is something which must succeed for, if it did not, very little else is likely to be successful in the world. Mr. Churchill has spoken of our fraternal association. Today the free world is a big place: it covers a great area and contains many peoples. If the free world is to remain big as well as free, our association must continue healthy, vital and constructive.

The world in which we live and work is full of toil and trouble: we live on a plateau of tension and it seems unlikely that for many years the world can become a comfortable place. Yet we do not believe that war is inevitable. We think that if we develop sufficient strength the temptation to aggress will diminish. The potential aggressor will think and think again as he sees there are no soft victories or quick returns. We are ready to talk with the nations on the other side of the Iron Curtain when they are ready to do so. We believe the time will come when they will feel constrained to seek for areas of agreement because they have ceased to be able to impose their will. It is therefore no mistake but common sense to look forward to years of tension and difficulty, but there is reason to think that patience, resolution and strength on our part will mitigate the stresses and gradually diminish the difficulties that confront us.

I do not agree with those who deplore our unhappy fate in having to live our lives at this time. It is true that we shall not live in comfortable security. It is true that we shall not be able to take peace and progress for granted as our Victorian forebears did. But the world has seen many centuries which shared the characteristics of our own. We are offered opportunities, great opportunities, to make the things in which we believe prevail. That there are difficulties to be overcome is not a cause for despondency. The thought belongs neither to your tradition nor to ours. Think of the great story of the conquest of this continent by the American people. There were endless difficulties to be overcome, privations to be endured, blows of fortune to be repelled. Yet you were masters of your fate and subdued the continent.

If we use rightly the great inheritance of our tradition, one or two elements of which I have mentioned today; if we forge truly in the discipline of the Liberal Arts the weapons of right judgment and constructive criticism: then we know our directions for the future and we have the power to move towards them. Our countries will never feel old or worried or uncertain if we keep a lively consciousness of the positive values and the great constructive principles we have discovered and wrought out of our experience. We know that the effort is worth-while. We know that each of us has a life to live that is valuable and can add value to our society. We know that in the company of our friends we have strength. Let hope, not fear, be our counsellor.

I close with a sentence from a letter of that Earl of Dartmouth who was your first great benefactor and whose name you bear. It has the grace of language cultivated by the 18th Century. "If by these few observations, for I purposely avoid encroaching upon your time, I may be able to induce you to turn your mind to the subject, I am satisfied."

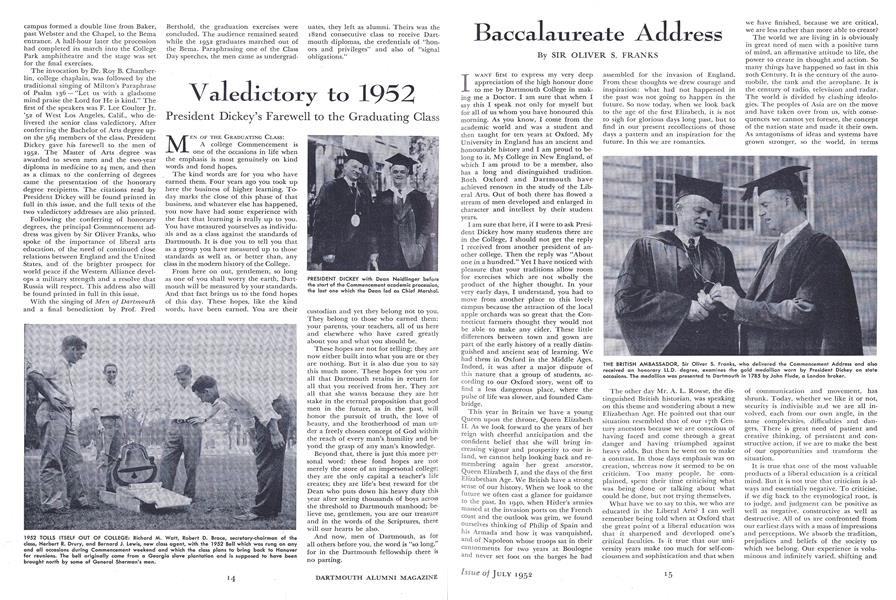

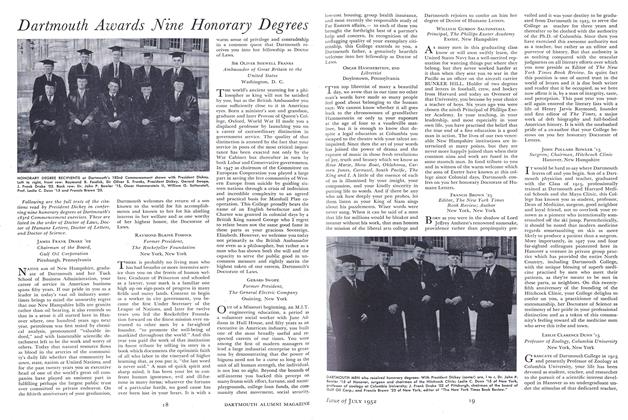

THE BRITISH AMBASSADOR, Sir Oliver S. Franks, who delivered the Commencement Address and also received an honorary LL.D. degree, examines the gold medallion worn by President Dickey on state occasions. The medallion was presented to Dartmouth in 1785 by John Flude, a London broker.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleThe Fifty-Year Address

July 1952 By E. BRADLEE WATSON '02 -

Article

ArticleThe 1952 Commencement

July 1952 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Awards Mine Honorary Degrees

July 1952 -

Class Notes

Class NotesThe Big 25th for 1927

July 1952 By DOANE ARNOLD '27 -

Class Notes

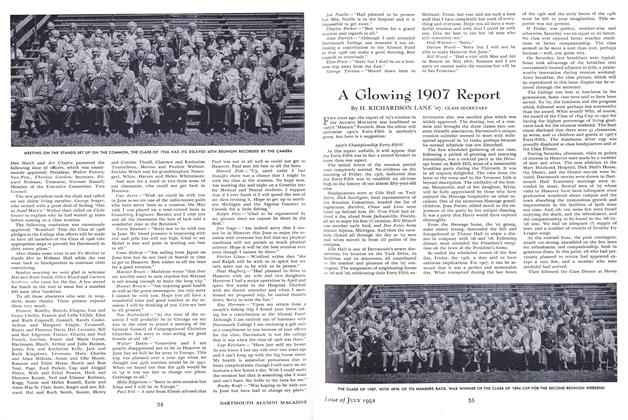

Class NotesA Glowing 190 7 Report

July 1952 By H. RICHARDSON LANE '07 -

Class Notes

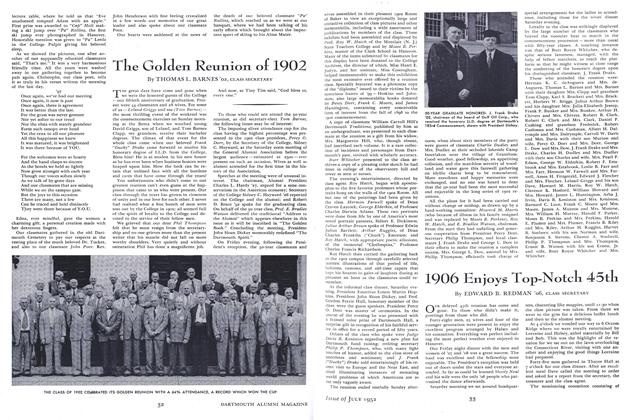

Class NotesThe Golden Reunion of 1902

July 1952 By THOMAS L. BARNES '02

Article

-

Article

ArticleMILITARY REVIEW FOR THE TRUSTEES

December 1918 -

Article

ArticleEditorial Comment

JANUARY, 1927 -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH STUDENT EXPENSES INCREASED IN ESTIMATE

FEBRUARY, 1927 -

Article

Article1982

MAY | JUNE 2016 By —Robin Shaffert -

Article

ArticleThe Student's Lot

January 1951 By C. E. W. -

Article

ArticleVarsity Schedules

DECEMBER 1970 By JACK DEGANGE