At the annual Commencement meetingof the General Alumni Association a traditional feature is the address deliveredon behalf of the honored Fifty-Year Class.The 1902 address, which follows in full,was given by Professor Watson at themeeting in Alumni Gymnasium on Saturday, June 7.

PRESIDENT HARDY, President Dickey, Mr. Hayward, Mr. Brace, fellow men of Dartmouth, and I have the special pleasure of adding, for the first time in the annals of your Association, fellow ladies of Dartmouth:

In paying this respect to our feminine retainers I recall a tribute to them at the Webster Centennial, the most distinguished event of our college years—except, of course, the graduation of the Class of 1902. Edwin Webster Sanborn, grandnephew of Daniel and great benefactor of Dartmouth, told of a Vermont farmer who read in his local paper that in India a wife could be purchased for $14. He pondered this exciting news and then in the best Vermontese rendered his verdict: "Wull, if she's a good 'un, she's wuth it." Then, too, when we sing of Eleazar and his 500 gallons we ought to remember there was a Mrs. Eleazar around and with her a bevy of proper ladies from the pious town of Lebanon that is, Lebanon, Connecti- cut—who saw to it that their men folks didn't get out of hand.

In spite of the flattering introduction of your President, I am seized with a panic of modesty as I stand here to do justice to my modest, "well, hardly ever" immodest class which left the Hanover plain 136 strong just fifty years ago. Some of our members had made a big stir in college, and some have made a much bigger one in the world, but I have had difficulty to make them confess to these crimes.

Our campus fame was largely athletic. Captained by Jack Cannell our track team won all inter-class events. George Pattee was captain of varsity track and sprinters "Louis" Dow and "Mose" Perkins, champion hurdler Pearl Edson, and two-miler Charles Goddard starred on the team. Our "Dike" Varney was tennis champion and pitcher on the first Dartmouth ball team to defeat Harvard. Our Guy Abbott formed and captained the first Dartmouth basketball team. We gave to Dartmouth football Jack O'Connor, star player, captain, and later a great coach.

I can think of no good reason why I no athlete at all should now be speaking for a class whose motto might be: Actions speak louder than words. As a freshman, it is true, I somehow managed to jump on to my rented piano box and in language more vigorous than elegant, saved it on its way to a football bonfire for which feat I was dubbed "Watty the boy orator." I have the same ominous feelings here today, although flames have not yet appeared.

My only other encouragement was given me by Dr. Tucker with a touch of his matchless humor too seldom recorded. I was then a member of the "Kid Faculty." He stopped me on the campus and said, "Watson, I am often asked to recommend speakers for high school commencements. Will you accept an invitation?" Swelled with vanity I stammered I would. "Very well," said the crisp but genial "Prexy," "I will send you a request I have received. I am sure you will meet the requirements." Something suspiciously like a twinkle was in his "ten-thousand-dollar eyes," as he turned to go with that clear-cut, easy, purposeful gait that made someone remark: "To see President Tucker walk is to know the perfect gentleman."

The letter came and with it my deflation. The South Royalton principal had written: "Dear Dr. Tucker, Can you find us a commencement speaker? But for goodness' sake, send someone who will not talk on too high an intellectual plane."

Now some of my classmates could and perhaps would do just that. It is some comfort to me to imagine what you have escaped, for we have a formidable number of "brain-trusters" but politically harmless ones. All 23 of them have IQ's much higher than mine: Julius Arthur Brown, for instance, Dartmouth's first Rhodes Scholar, who now presides over Florida's Jacksonville Junior College, having retired from a long career as teacher of physics and astronomy, first at Dartmouth and later at Beirut University in Syria, bulwark of Americanism in the precarious Middle East. He is a worthy representative of his family and his college, for he is a great grandson of that President, Francis Brown, who, with the help of Daniel Webster, saved Dartmouth as a free and independent college.

Four of our class have recently been members of the Dartmouth faculty, three of them Leland Griggs, William Murray, and Arthur Chivers doing us high honor until I came from Istanbul 29 years ago to lower their "intellectual plane." Others have held professorships in the Universities of lowa, Kansas, and Colorado. With us today is George Elderkin, archeologue of Princeton and one-time director of the American archeological school of Athens; also Hermon Farwell, professor of physics at Columbia; Roy Hatch, our faithful class agent, author and professor of social education at Montclair's State Teachers College; Tom Barnes, able and beloved principal of the East Orange, N. J., High School. Most noted of all, perhaps, was Philip Fox, astronomer at Northwestern and director of the Adler Planetarium in Chicago. For outstanding service in war he was decorated by France, Greece, and Great Britain.

I have mentioned our teachers first because we are here to give thanks for an education. In the fantastic elaboration of the American college, the teacher should be more frankly recognized as the focal point. He was when Dartmouth was founded, when class method was animated discussion between teacher and pupil. Students were not merely primed to think they practised thinking.

It is time to ask if our colleges are not going the way of our motley cities, "the trouble with which," wrote columnist Pearson, "is too many people in too small an area trying to do too much in too short a time." Confusion is inevitable. The academic mind is approaching the state of the Yankee farmer's, who, when asked to donate to the village church, shouted: "I'm an atheist, thank God!" The teacher, too, is caught in the scramble. A leading university authority confided to me that he had to work from 11:00 P.M. to a:00 A.M. to accomplish anything himself.

I like to recall the words of President Nichols spoken as he conferred an honorary degree on Charles Francis Richardson, the idolized "Clothespins" of our college generation:

"Since the beginning of the world, there have been three dominant professions: the ruler, the warrior, and the teacher. Of these the voice of the teacher has ever been raised in the greatest service and has ever earned the greatest love."

In other fields our classmates have won higher renown: Henry Pillsbury, Physician-General of the army, organizer of hospitals in World War II; Arthur Ruggles, recently a Trustee of the College, outstanding psychiatrist, for 26 years superintendent of the Butler Hospital of Providence, R. I.; our class secretary, Philip Thompson, honored physician of Portland, Me.; George Graham, nationally known pathologist; Davis Keniston, Chief Justice of the Municipal Court of Boston; Dennis Lyons, general counsel of the Northern Pacific Railway; Dan Cushing, Chicago lumber magnate and one-time Mayor of Bogalusa, La., also member of the governor's staff; Kendall Banning, poet, journalist, dramatist, and historian of army and navy; Allan MacKinnon, head of the law department of the Boston and ...Maine Railroad; Robert Estabrook, General Manager of the New England Telephone and Telegraph Co.; Ben Riley, prominent engineer of refrigeration in Detroit; Charles Goddard, journalist, dramatist, and pioneer in movie serials; Percy Dorr, our class president for a record period of 50 years, and Bert Briggs, wise counsellors in investments and banking; in real estate, George Lincoln Dow of Cambridge, Mass., George Hubbard and Pearl Edson of New York City, the latter the inspirer of the Tudor City development.

These are samplings only, for my time is limited; but I must not omit the story of our Bob Smith. To quote our class secretary and a wise and understanding physician, "Dr. Bob," as his followers affectionately called him, "saved more lives than is often given the power of one individual." He had abused academic liberty, as many more do today, to become in middle life a hopeless inebriate. He gathered in his Akron, Ohio, kitchen a group of fellow addicts and pledged them to mutual aid in resisting the cause of their ruin. And so Alcoholics Anonymous was founded. It now numbers 150,000 members in 38 countries. It has been truly said: Dr. Bob "became the keystone of the arch under which about 100,000 alcoholics have marched to freedom."

One other member both the College and our class holds today in highest honor. He is James Frank Drake, known biologically on campus as "Ducky." He was a friendly, likable fellow from Kimball Union Academy who came to enjoy his college so well that with Percy Dorr, our president, he vowed to attend every commencement when possible. He has kept the promise and is here today.

As financial adviser and generous donor he has rendered Dartmouth invaluable service. He has presided over alumni associations including this General one, served on the Alumni Council, and never lost touch with undergraduate life through his fraternities, the Tuck School, and the college teams. In a very real sense he is the product of Dartmouth experience at its best.

Only eight years out of college he became the youngest President of the Common Council of Springfield, Mass. As Lt.- Colonel, charged with ordnance finance, he won great esteem. After World War I, he rose quickly to be president or vice-president of so many companies and corporations, including Pullman and Gulf Oil, that I will not attempt to list them. For 17 years he was president of the Gulf Oil Corporation and is now its chairman of the board, besides holding nearly fifty other such offices.

I advise the reading of his corporation's semi-centennial history, Since Spindletop the story of incredible scientific adventure and service to myriads. Dartmouth has its own good reason for pride in such a story, because the idea of exploiting oil from the earth was first conceived here one hundred years ago in Dr. Dixi Crosby's office; and a Hanover and Dartmouth boy, George H. Bissell, donor of our original gymnasium, pushed the idea to a successful issue in the first Pennsylvania "oil strike" in 1859.

I wonder how "Ducky's" unswelled head can carry so much. It still looks quite as it did marching with us in a nightshirt "peerade" to the "June" to "inspire" a traveling circus or Ten Nights in a BarRoom or perhaps mobbing the midnight train with the "famous 200" to reach Williamstown in time to cheer our defeated ball team to victory in a second game.

The elder Mr. Rockefeller, while sitting to the sculptor Jo Davidson for his mammouth bust, told him the story of a prosperous Westerner who came to New York to engage an artist to do a portrait of his father. He found one with the help of a hotel clerk. The artist asked, "When will your father sit for me?" "Never," said the Westerner, "he's dead." "So you want me to paint him from a photograph?" "No, sir, he never had one taken, but I can tell you just how he looked." The artist needed money too badly to turn down the offer. He listened to the description of ears, eyes, nose, and mouth, and when the patron returned from Europe, the portrait was ready. The Westerner viewed it long and judiciously and with tears in his eyes he blubbered: "Yes, dear father, that is you; but my goodness how you have changed!"

I felt much the same about my alma mater, but without any tears, when I returned in 1923 and saw the New Dartmouth that our good friend of student days, Ernest Martin Hopkins, had created. How it had changed in the 15 years of my absence and how miraculously! not merely because of more students and more buildings that replaced the rambling colonial row from the Commons to Crosby and were still springing up on every available lot, or because the Baker Library was soon to add its majestic tower to the campus skyline. I could make other comparisons that too few of our returning alumni can, for I was entering again into the life these buildings housed. In classrooms and in campus activities I met a wonderful new generation of students. They are still too little known to alumni except for their athletic vigor and occasional boyish lapses sensationally featured in the press. Like a Rip van Winkle, I found it difficult to convince my colleagues who had known them right along that these boys come to college better prepared, with more acute and receptive minds, and thanks to the selective system with better mental fibre than those I had known here before 1910. They are not titans of intellect, of course, but it is unthinkable that any of them could write, as a member of an earlier class of mine did: "In Memoriam was written by Henry Wordsworth Longfellow on the centenary of his graduation from Harvard University in honor of the dead ones in his class." On the average they do more and better college work. I am not speaking of individuals. The really creative student fits into no average or pattern, nor does the slacker. As President Tucker once said in a vespers talk: "No college ever educated any man; a few men have educated themselves in college."

This same great president had brought about a new era of student behavior. He had lessened the rowdy customs of the heman tradition, notably the practice of "horning." This was a mob protest in the dead of night at the home of some unfortunate professor, fish-horns replacing the trumpets at the walls of Jericho. One had occurred shortly before we entered college. Dr. Tucker, then on an alumni tour, canceled appointments and suddenly appeared in Hanover. He expelled the ringleaders. He later pardoned them at the request of the student majority, who were ashamed of the affair and made a pact that complaints would never again be presented in this hoodlum fashion a promise that with one recent inexcusable exception has been kept to the betterment of student dignity and Dartmouth's good name. I am glad to assert that during my years of teaching the behavior of the student body under its own governing agencies and in the management of its activities has been both cooperative and responsible. I believe it will long continue so.

In the unreflecting zest of youth, let them never forget the truth that prompted President Dickey and our Trustees to establish the timely William Jewett Tucker Foundation for their moral and spiritual quickening. "This purpose of the College," President Dickey has said, "springs from faith in the ability of men to choose between (good and evil) and from a sense of duty to advance the good," a purpose at Dartmouth that has "carried through the years of nearly two centuries; never has it been set aside."

To replace our admired professors has also come a new generation of American scholars too many for one student to know them all as we knew ours, but more familiar, and on a more friendly level, to those they instruct. The old stiff faculty- student etiquette has gone touching the cap to the prof and tipping it to Prexy but, then, caps, except for freshmen, have gone, too.

In this impressive evolution there are inevitable dangers: one being over-specialization. We do well to remember the advice given by President Tucker to a student who asked what courses to take to prepare him for the law. "Prexy" replied: "While in college, elect as far afield of your specialty as possible; you will never have another chance to acquire a broad education."

There is also the danger I mentioned earlier of lessening the teacher's effectiveness in the intricate machinery of the modern college. This threat is less at Dartmouth than elsewhere, but there is a tendency for students to depreciate courses, however valuable and well taught, and to seek liberty from instruction before they are fitted to make wise use of it.

The expansion of campus activities has also been distracting. Within limits I believe in these: they are often educational and provide practical training. To cite only the Players', that I happen to know best, they now stage from six to eight peiformances a year and have a staff of three or four expert directors and technicians. In our student days, the Dramatic Club gave only one and imported an outsider to coach. The results were surprisingly good; they are infinitely better today.

These tendencies have not yet lowered the values of college. They need not lessen our pride in the New Dartmouth. It is good for old grads to be nostalgic it's a balm to the soul in these days of perplexity. But let us not blind ourselves to the increasing greatness of our college.

In 1789 George Washington addressed to President John Wheelock and his trustees an autograph letter. In it he described them as "guardians of a seminary and an important source of science." He mentioned the aims of the new democracy. He confidently added that from this "seminary" he and his fellow workers ' are to derive great assistance."

Dartmouth is still fulfilling his great expectation. There is no better way for a college to serve democracy than by an honest liberalism that is Dartmouth's historic aim; to teach not what to think but how to think and how to know the facts on which sound opinion must be based. This is not propaganda nor subversion; it is conscientious guidance in the search for truth.

Our progressive young president, John Sloan Dickey, is keeping the College true to its course and is opening its portholes still wider upon the whole world. He means to make Dartmouth's share in America's great task the schooling of a sound and enlightened leadership.

It is gratifying to our class that he, like his eminent predecessor, harks back for inspiration to the words it was our unforgettable privilege to hear in President Tucker's firm, magnetic voice, to which we listened as it was said the Jacobeans hung spellbound upon the words of their Lord Keeper, Francis Bacon, for fear we might lose a syllable.

With what of our strength remains, we of 1903 pledge our aid in Dartmouth's everincreasing service to our land.

"What is more pleasurable," Cicero asked, "than an old age crowded with the enthusiasm of youth?" That is our pleasure today as we renewour contacts with this youth-giving college. We have caught the spirit of her perennial call, voiced by Dr. Tucker 40 years ago in words that should linger in every graduate's mind:

"Come back to the college as you can, not only to see but to feel its expanding life. Come back at commencement, but come at other times. . . . Do not rely too much on your memories for your idea of college work. ..."

And I end by giving you his immortal toast: "The college of today, younger by the years which make us older, rich in the wealth of the new knowledge; may we learn to renew our intellectual life in hers."

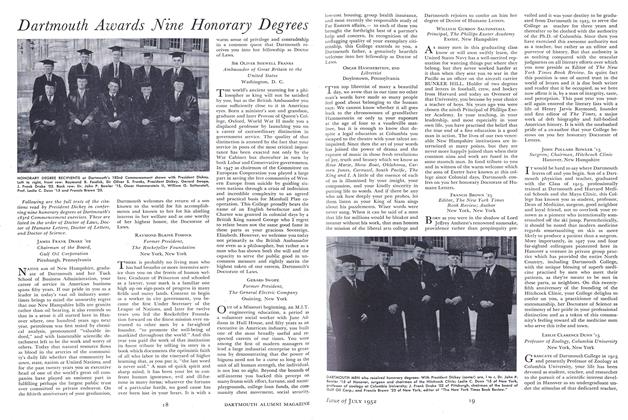

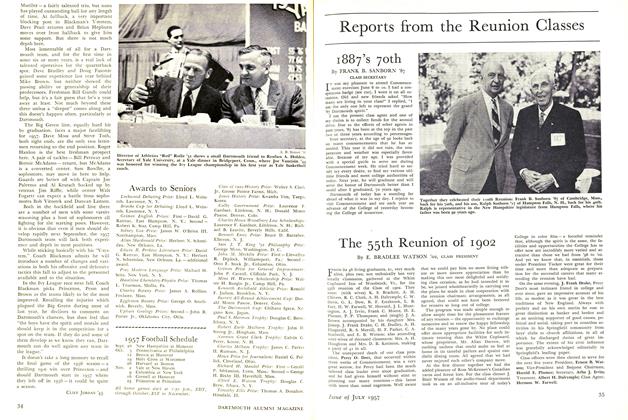

50-YEAR SPEAKER: E. Bradlee Watson '02, Professor of English Emeritus, who delivered the traditional address on behalf of the 50-Year Class.

THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE GENERAL ALUMNI ASSOCIATION IN THE GYM, JUNE 7

PROFESSOR OF ENGLISH, EMERITUS

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleThe 1952 Commencement

July 1952 -

Article

ArticleBaccalaureate Address

July 1952 By SIR OLIVER S. FRANKS -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Awards Mine Honorary Degrees

July 1952 -

Class Notes

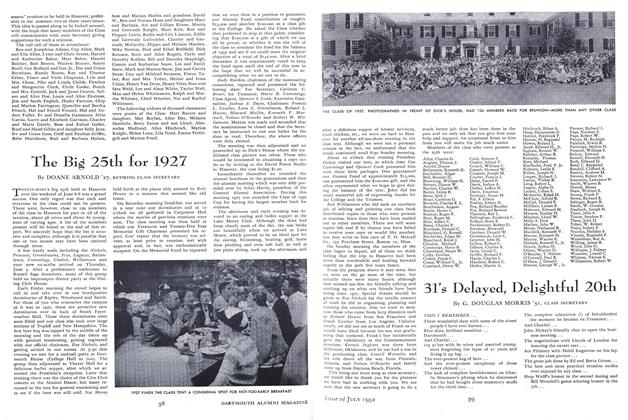

Class NotesThe Big 25th for 1927

July 1952 By DOANE ARNOLD '27 -

Class Notes

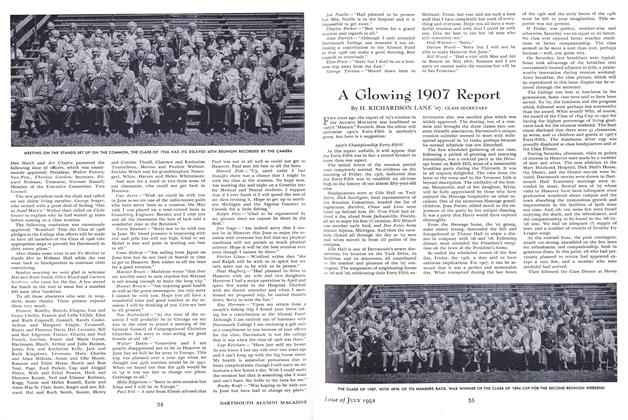

Class NotesA Glowing 190 7 Report

July 1952 By H. RICHARDSON LANE '07 -

Class Notes

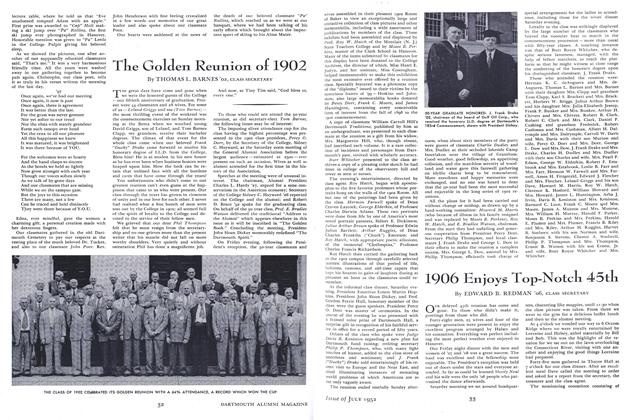

Class NotesThe Golden Reunion of 1902

July 1952 By THOMAS L. BARNES '02

E. BRADLEE WATSON '02

-

Books

BooksFLETCHER, BEAUMONT & Cos.,

May 1947 By E. Bradlee Watson '02 -

Books

BooksSAGE OF THE SACRED MOUNTAIN.

March 1954 By E. BRADLEE WATSON '02 -

Books

BooksTHE MAGNIFICENT PARTNERSHIP.

March 1955 By E. BRADLEE WATSON '02 -

Class Notes

Class NotesThe 55th Reunion of 1902

July 1957 By E. BRADLEE WATSON '02 -

Books

BooksTHE JADE NECKLACE OF LIN SAN KWEI.

MARCH 1959 By E. BRADLEE WATSON '02

Article

-

Article

ArticleOctober Schedules

October 1939 -

Article

ArticleRobert C. Hill '42,

APRIL 1971 -

Article

ArticleThe White Death Shark

November 1976 By BERL BERNHARD '51 -

Article

ArticleShakespeare...That is the Question.

May 1995 By Dawn Conner '95 -

Article

ArticleROWING

JULY 1970 By JACK DE GANGE -

Article

ArticleBridgeport

JUNE 1967 By RICHARD H. MACDONALD '44