A YELLOWING clipping from the BostonSunday Globe, dated North Adams, Mass., June 3, 1911, reads: "College Men in Balloon Race; Dartmouth Airship Lands Early in Pelham; Pennsy and Williams Are Yet To Be Heard From."

Reminded of this event during a relaxed "social" gathering of a recent Hanover football weekend, I grew bold and claimed no senior graduating from Dartmouth had ever been so "up in the air" around Commencement time as I had been.

My claim originates back in the days when Fred Harris '11 was persuading a few outdoor-minded undergraduates to soar through the air on skis. The Dartmouth Outing Club and its Carnivals are a bright memory for forty classes of Dartmouth graduates, but the contribution to aviation of the Dartmouth Aero Club remains unsung.

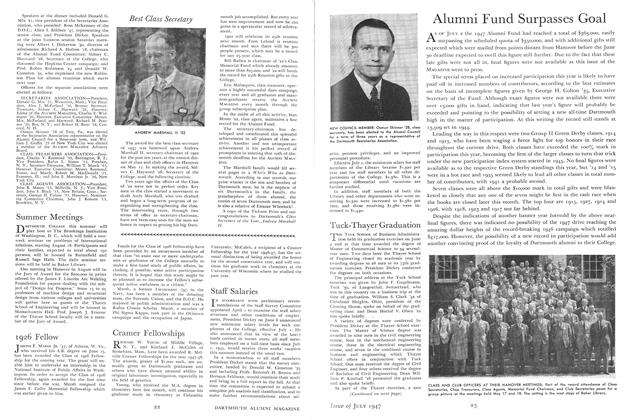

The story starts on a frosty December night in 1910 when sixty undergraduates, seeking extracurricular relief from the tedium of classroom discipline and booklearning, and stimulated by aviator Glen Curtiss' winning the New York Times prize for a continuous flight from Albany to New York, gathered at College Hall and founded the Dartmouth Aero Club. Jay B. Benton '90, city editor of The BostonTranscript, had pepped up the meeting by inviting the two most productive members to join him on a balloon ascension in the spring. Membership was restricted, after "consultation with aeroplanists of Harvard, Cornell and Pennsylvania," to those who wanted to "experiment with a glider, or such men as are interested merely in the scientific study of aeronautics."

The list of officers included Richard F. Paul '11, Louis P. Hall '11, Howard B. Lines '12, Lester W. Snow '12 and Harry H. Semmes '13. The budding public relations and financial genius of James M. Mathes '11 landed him in the tough job of treasurer. Having talked too enthusiastically, I was elected president.

The Aero Club membership was quickly beguiled by the blandishments of magazine publishers and circulation builders. Weeks of soliciting subscriptions to Aero Magazine from the 1200 undergraduates of that period landed the grand subscription prize of a glider.

Consternation filled the ranks of the club membership when the glider was uncrated in the slush of March. It weighed a ton, it seemed. Housing was lacking for its forty-foot wing span. News that the nearest reliable glider soaring breeze was in far-away Elmira, New York, did not filter through until the twentieth reunion of the class of 1911.

Imagination was rife, however. Some club member, nettled by the prosperity of the Outing Club, suggested that the club president journey to the nearest steep hill and attempt glider flights on skis. To make the tale of back-breaking attempts short and snappy, the final try accomplished a record leap (for Grafton County, anyway) of 26 feet. The crash demolished the glider. What a break that was! I've often wondered about the outcome if the darn thing had really started soaring over forestcovered Mink Brook.

Blue skies of a lovely Hanover spring stimulated the club membership to fresh achievement. Plans for an intercollegiate balloon race were undertaken, with Harvard, Pennsylvania, Williams and Amherst. Mr. Jay Benton's balloon ascension invitation was recalled. The club president was unanimously elected as Mr. Benton's racing aide. Mr. Benton, ever loyal to Dartmouth's highest interests, promptly signed up his balloon Boston, all expenses paid. All efforts of the president to call a meeting and tender his resignation were rebuffed.

The Williams College Aero Club, hosts of the race, scheduled the take-off at the lee side of the nearest gas works. Prevailing winds were from the west; a rod or two to the east of the teeming city of North Adams, Hoosac Mountain reared its craggy head.

After a notably hospitable evening at Williams, designed to put the Icaruses of 1911 into a "higher than a kite" mood for the morrow, contestants were shooed over to North Adams on Saturday noon. Mr. Benton, with balloon, was waiting, checking his weather-eye with famed balloonist Leo Stevens, official starter. Mr. Stevens had declared to the assembled press: "This starts intercollegiate ballooning as the only air sport for colleges. Aeroplaning is killing a man a day. The spherical balloon is the only safe instrument for those wishing sensible but exciting air rivalry and amusement."

Suddenly the gas man presented the writer, whose cash resources totaled $11, with a $45 gas bill and a document reading: "The undersigned releases the North Adams Gas Light Company from any expense, responsibility or damage, to us or others, directly or indirectly." Confusion reigned until Mr. Benton arrived with his pen and ampler wad.

The Harvard and Amherst entries failed to show up, but Professor David Todd of Amherst had telegraphed: "Hearty congratulations to all. Will watch. May the best bubble win." What do you mean, Professor, by "bubble," I thought to myself.

The Dartmouth entry, swelling with its 35,000 cubic feet of illuminating gas, tugged at its drag rope. A five-foot-square, four-foot-high wicker basket, decked with six bags of sand ballast, eighty pounds each, hung from the balloon. While waiting our turn to start, Mr. Benton chatted away and I chattered my response. He tried to reassure me: ballooning in New England was delightful; the chief danger was in being blown out over the Atlantic Ocean. "That calls for fast action with the gas rip-cord when the pilot sees the sea," said Mr. Benton.

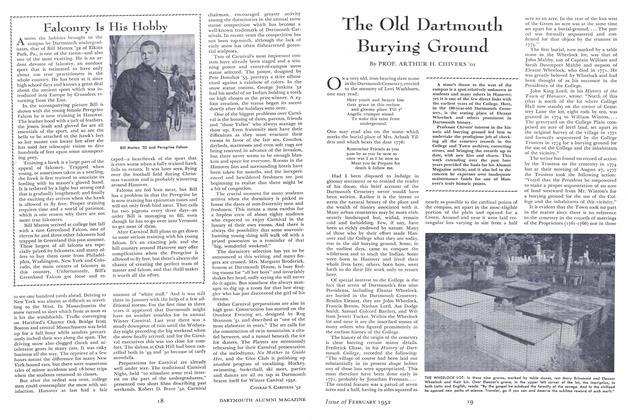

The adjoining picture accompanied the local newspaper report. "Under bright skies, in the presence of several thousand spectators and a wind from the west, contestants from Pennsylvania, Williams and Dartmouth departed, in that order, on the first intercollegiate balloon race.

How we vaulted into the basket is not clear to me today. Vivid, however, is the impression that the westerly wind had suddenly become quite "pert." And still vivid is Mr. Benton's strident call, "Heave in and untangle the ropes." He had spied high powered electric lines in the offing. Beyond were numerous chimney tops, just duck-pins for the drag-ropes which kinked into large balls.

"Heave it is," I thought, as I h'isted myself up the basket side, racing low over the house tops. I struggled with the ropes. Heaves! Whoops! and Burps! left me weakly "hanging on the ropes."

Suddenly Mr. Benton apprehended Hoosac Mountain rearing its forbidding boulders high above our path. ' Dump sand," cried Mr. Benton, as he sensed the catastrophe of being dashed and/or bashed to death on the mountain. Still bushed from wrestling with the ropes, I balanced on the basket rim for a go at a sand bag. I still don't know whether it was the cookies I tossed or the sand I spilled that lightened the load enough for us to leap Hoosac Mountain, in the nick of time, with 3⅝ inches to spare.

So far, I thought to myself, isn't ballooning just ducky? I know of easier ways to "get up in the air." But once again, as an annal of history, stout heart and hidden strength had surmounted adversity and crisis. Soon the peace and quiet of ballooning dominated the scene as we soared into the empyrean to two miles above sea level. We scanned the heavens for our rivals. To the north the Williams balloon was bobbing about in the lightning flashes of a thunder storm. Closing my eyes, I mentally wafted thoughts of good-will and hope in their direction. To the east, over the sharply defined Vermont-Massachusetts boundary line, the Pennsylvania balloon sped on, way ahead.

Mr. Benton concluded that our dragging start had imposed a severe racing handicap on us. I have a hunch, also, that he enjoyed the sights of the Deerfield River Valley more than he did the constant chore of spilling sand, or releasing gas, in the search for the fastest moving air currents.

A cloud covered the sun. In the suddenly chilled air the balloon dropped. "How fast are we dropping?" I asked Mr. Benton. "Toss out some torn newspaper and guess," he replied. The sun emerged and up we soared. Soon the instruments showed a range in elevation from 10,000 to 3,000 feet with temperatures ranging from 110° to 38°.

The silent, hushed tranquillity of a balloon journey impressed me. Mr. Benton provided a lunch. As I drank my coffee, Mr. Benton constantly shifted his twohundred-plus avoirdupois to drink in the scenery. How the wicker basket cracked and creaked! I wondered if the basket maker really took pride in his work when he tied the basket bottom to the sides.

"If you want to see some action," Mr. Benton said, "call out to the folks at the next farm house we pass over. I still hang my head with shame as I recall my sophomoric response: "Stop beating your wife! I said in a firm tone to a couple sitting on their lawn. When last seen the couple were still running around, looking all over the place for the intruder. Not once, as I called out, time and time again, to engage folks in conversation, did anyone ever think to look heavenward.

The winner of a balloon race, dear reader, is the pilot who travels the longest distance in a straight line from the starting point. About 5 p.m., as we reached the Connecticut River above Northampton, a breeze from the north turned us down river. Beyond Springfield, a seaturn zephyr sent us back up the river. In vain I scanned Mt. Holyoke's campus, looking for a wave of encouragement from my sister. At Greenfield, the down-river breeze took over again. For an hour we commuted, back and forth, up and down the Connecticut River Valley.

Shortly after 6 p.m. clouds darkened the sinking sun. At the time I didn't realize the effect of the sudden atmospheric change on the lifting power of the unspent gas. All I sensed was that suddenly we were plummeting landward, like a bat out of hell. The earth appeared to be swallowing us up. Let's get this over with, I thought, as I hoisted a leg over the basket edge for a leap to terra firma.

Zowie! It seems that the remaining gas more than balanced the ground-level atmosphere. The resulting bounce of hundreds of feet into the air left me bottom side up on the basket bottom. Mr. Benton knowingly clung to the basket side. "Pull the gas rip-cord," said Mr. Benton, if you are in a hurry to get out." A whoosh of gas followed a yank at the cord. The next sensation was that of a leap from a third story window as the basket hit the ground with a thud. Mr. Benton remembered to note the time. It was 6:17 p.m.; the place—West Pelham, Mass.

Fortunately we had missed some woodlands and landed in a pasture. Twenty cows stood waiting to be called into the barn. It was milking time, in June. At our sudden intrusion, pandemonium-or whatever dumb animals experience—possessed the cows. They didn't give milk so good that night, we learned later.

Meanwhile a dying breeze lazily dragged the precious silk gas bag along a barbedwire fence. The sound of the tearing and ripping silk was awful to hear. It was not music to Mr. Benton's ears.

A farmer loaded the torn bag and the basket into a cart for shipment back to Boston. Mr. Benton and I hopped an open trolley car to Amherst. I spent the evening at Mt. Holyoke imaginatively amplifying to my sister and friends the experiences of the afternoon. The next day, at my home in Concord, N. H., I learned that Father had sat out on the lawn all afternoon in case his son happened to blow by. "Every time a cloud darkened the sun," Mother said, "Father would rush into the house and call, 'Here comes John, Mother!' "

Oh yes—who did win the race? Dartmouth's entry started last and finished last. Somehow that makes sense. Due to the right-angle southward detour we took at Northampton, we never did catch our "second wind." The sashaying we did up and down the river scored us only 41 miles travel credit from the starting point. Our time in flight was three hours and fifteen minutes.

The Williams balloonists, H. P. Shearman and aide Kenneth T. Price, finished second, landing at Paxton, Mass., at 7:45 p.m. with a flight credit of 66 miles in five hours. Reporting an exciting trip, they claimed they "narrowly escaped freezing to death, caught in a whirlwind that rushed them to a height of 12,000 feet at a rapid rate!"

The winners, Arthur T. Atherholt and aide George A. Richardson, Pennsylvania, credited with 110 air miles, stayed aloft seven hours and landed in West Peabody, Mass., six miles from the Atlantic Coast. "The flashing Baker Island lighthouse, off Salem, caused me to drop my balloon through the darkness and a drenching thunder storm into some woods," Pilot Atherholt reported. Their basket sheltered them for the rest of the night.

"What contribution did the Dartmouth Aero Club make to aviation?" someone may well ask. Who knows but what a country lad, residing in the Deerfield River Valley, the Charles Lindbergh or Eddie Rickenbacker of tomorrow, had glimpsed the Dartmouth balloon floating majestically overhead? Who knows, as the lad fell asleep on the night of June 3, 1911, but what he resolved that he too would some day sail the great blue yonder and make aviation history? Who knows?

GASSING UP: THE DARTMOUTH, WILLIAMS AND PENNSYLVANIA BALLOONS HALF FILLED

BACK TO EARTH: John Pearson '11, author of this amusing recollection of balloon racing, is Managing Trustee of the Institute for Associated Research in Hanover. He was formerly head of the Dartmouth Eye Institute, from 1940 to 1947.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

February 1952 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR, RICHARD P. WHITE -

Article

ArticleThe Old Dartmouth Burying Ground

February 1952 By PROF. ARTHUR H. CHIVERS '02 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1950

February 1952 By ENS. SCOTT C. OLIN, USN, SIMON J. MORAND III -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

February 1952 By WILLIAM ANDRES, EDWIN C. CHINLUND, JACK D. GUNTHER -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917

February 1952 By KARL W. KOENIGER, DONALD BROOKS, GILBERT N. SWETT -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926

February 1952 By HERBERT H. HARWOOD, DONALD NORSTRAND, CARLETON BLUNT